Henry Williams (missionary)

| Henry Williams | |

|---|---|

.jpg) Williams about 1865 | |

| Born |

11 February 1792 Gosport, England |

| Died |

16 July 1867 (aged 75) Pakaraka, Bay of Islands, New Zealand |

| Nationality | British |

| Other names | Te Wiremu and Karu-whā |

| Occupation | Missionary |

| Spouse(s) | Marianne Williams (née Coldham) |

| Relatives |

The Revd William Williams (brother) Edward Marsh Williams (son) The Revd Samuel Williams (son) Henry Williams (son) John William Williams (son) Hugh Carleton (son-in-law) The Revd Octavius Hadfield (son-in-law) |

Henry Williams (11 February 1792 – 16 July 1867) was the leader of the Church Missionary Society (CMS) mission in New Zealand in the first half of the 19th century.

Williams entered the Royal Navy at the age of fourteen and served in the Napoleonic Wars. He went to New Zealand in 1823 as a missionary. The Bay of Islands Māori gave Williams the nickname Karu-whā ("Four-eyes" as he wore spectacles). He was known more widely as Te Wiremu.[1] ('Wiremu' being the Māori form of 'William'). His younger brother, William Williams, was also a missionary in New Zealand and known as "the scholar-surgeon".[2] Their grandfather, the Reverend Thomas Williams (1725–1770), was a Congregational minister at the Independent Chapel of Gosport.[3][4][5]

Although Williams was not the first missionary in New Zealand – Thomas Kendall, John Gare Butler, John King and William Hall having come before him – he was "the first to make the mission a success, partly because the others had opened up the way, but largely because he was the only man brave enough, stubborn enough, and strong enough to keep going, no matter what the dangers, and no matter what enemies he made".[6]

In 1840 Williams translated the Treaty of Waitangi into the Māori language, with some help from his son Edward.[7]

In 1844, Williams was installed as Archdeacon of Waimate in the diocese centred on the Waimate Mission Station.[8]

Parents, brothers and sisters

Williams was the son of Thomas Williams (Gosport, England, 27 May 1753 – Nottingham 6 January 1804) and Mary Marsh (10 April 1756 – 7 November 1831) who had married in Gosport on 17 April 1783. Thomas Williams was a supplier of uniforms to the Royal Navy in Gosport. In 1794 Thomas and Mary Williams and their six children moved to Nottingham, then the thriving centre of the East Midlands industrial revolution.[9] Thomas Williams was listed in the Nottingham trade directories as a hosier. The industry was based on William Lee's stocking frame knitting machine. The business was successful. Thomas Williams received recognition as a Burgess of Nottingham in 1796 and as a Sheriff of Nottingham in 1803.[9] However the prosperity which had been such a feature of the hosiery industry in the second half of the 18th century ended. In 1804, when Thomas Williams died of typhus at the age of 50, his wife was left with a heavily mortgaged business with five sons and three daughters to look after.[9][10]

Williams's parents had nine children, of whom six (including himself) were born in Gosport and three (including William Williams) in Nottingham:

- Mary (Gosport, England, 2 March 1784 – Gosport, England, 19 April 1786)

- Thomas Sydney (Gosport, England, 11 February 1786 – Altona, Germany, 12 February 1869)

- Lydia (Gosport, England, 17 January 1788 – 13 December 1859), married (7 July 1813) Edward Garrard Marsh (8 February 1783 – 20 September 1862)[11]

- John (Gosport, England, 22 March 1789 – New Zealand, 9 March 1855)

- Henry (Gosport, England, 11 February 1792 – Pakaraka, Bay of Islands, New Zealand 16 July 1867)

- Joseph William (Gosport, England, 27 October 1793 – Gosport, England, August 1799)

- Mary Rebecca (Nottingham, England, 3 June 1795 – Bethlehem, Palestine 17 December 1858)

- Catherine (Nottingham, England, 28 July 1797 – Southwell, Nottinghamshire, England, 11 July 1881)

- William (Nottingham, England, 18 July 1800 – Napier, New Zealand, 9 February 1878)

Williams was aged 11 when his father died (his brother William Williams was three).

1806–1815: Navy years

In 1806, aged 14, Williams entered the Royal Navy, serving on HMS Barfleur. He became a midshipman in 1807. He then served on HMS Maida under Captain Samuel Hood Linzee during the Battle of Copenhagen when the Danish fleet was seized in 1807. He landed with the party of seamen who manned the breaching battery before the city. On HMS Galatea, under Captain Woodley Losack, he took part in the Battle of Tamatave (1811) between three English frigates, under the command of Captain Schomberg, and three French vessels of superior force. Williams was wounded and never entirely recovered.[12][Note 1] For this service he qualified for the Naval General Service Medal, which was awarded in 1847 with clasp "Off Tamatave 20 May 1811".[13][14]

After the outbreak of the War of 1812 between Britain and the United States he served on HMS Saturn as part of the blockading-squadron off New York City. He was transferred to HMS Endymion and served under Captain Henry Hope in the action on 14 January 1815 against the American warship USS President. When the latter was forced to surrender, Williams was a member of the small prize crew that sailed the badly damaged vessel to port, after riding out a storm and quelling a rebellion of the American prisoners.[15] In 1847 the Admiralty authorized the issue of the Naval General Service Medal, with clasp "Endymion wh. President", to any still surviving crew from Endymion.

Before serving on HMS Saturn, Williams sat and passed his examinations for the rank of lieutenant, although he was not promoted to lieutenant until 28 February 1815, after the Treaty of Ghent was ratified by the United States. When peace came in 1815, he retired on half pay.[16] At the age of 23 he had been "in the North Sea and the Baltic, around the French and Spanish coasts, southwards to the Cape, up to the eastern shores of Madagascar, across the Indian Ocean to Mauritius, and northward to the coast of India. After service at Madras and Calcutta, it was on into the cold American winter and that epic last naval engagement in which he took part, on the Endymion".[17]

Williams' experiences during the Napoleonic Wars and the War of 1812 influenced his decision to become a Christian missionary and peacemaker in carrying out the work of the Church Missionary Society in what was then considered an isolated and dangerous mission in Aotearoa (New Zealand).

Marriage and children

After leaving the Royal Navy, Williams gained employment at Cheltenham, as a teacher of drawing.[18] His artistic skills are apparent in the drawings he made in New Zealand.[19] Williams married Marianne Coldham on 20 January 1818.[18] They had eleven children:[20]

- Edward Marsh (2 November 1818 – 11 October 1909).[21] Married Jane Davis, daughter of the Revd Richard Davis, a CMS missionary.

- Marianne (28 April 1820 – 25 November 1919). Married the Revd Christopher Pearson Davies, a CMS missionary.[22]

- Samuel (17 January 1822 – 14 March 1907).[23] Married Mary Williams, daughter of William and Jane Williams.

- Henry (10 November 1823 – 6 December 1907).[24] Married Jane Elizabeth Williams (also a daughter of William and Jane).

- Thomas Coldham (18 July 1825 – 19 May 1912). Married Annie Palmer Beetham.

- John William (6 April 1827 – 27 April 1904). Married Sarah Busby, daughter of James Busby.

- Sarah (26 February 1829 – 5 April 1866). Married Thomas Biddulph Hutton.[25]

- Catherine (Kate) (24 February 1831 – 8 January 1902). Married the Revd Octavius Hadfield.

- Caroline Elizabeth (13 November 1832 – 20 January 1916). Married Samuel Blomfield Ludbrook.

- Lydia Jane (2 December 1834 – 28 November 1891) Married Hugh Carleton.[26]

- Joseph Marsden (5 March 1837 – 30 March 1892).

Missionary

Edward Garrard Marsh, the husband of their sister Lydia, would play an important role in the life of Henry and William. He was a member of the Church Missionary Society (CMS) and was described as 'influential' in the decision of Henry and William to convert to Anglicanism in February 1818,[5] and then to join the CMS.[27] Williams received The Missionary Register from Marsh, which described the work of CMS missionaries. Williams took a special interest in New Zealand and its native Māori people.[28] It was not until 1819 that he offered his services as a missionary to the CMS, being initially accepted as a lay settler, but was later ordained.[29]

Williams studied surgery and medicine and learned about boat-building. He studied for holy orders for two years[17] and was ordained a deacon of the (Anglican) Church of England on 2 June 1822 by the Bishop of London; and as a priest on 16 June 1822 by the Bishop of Lincoln.[30]

On 11 September 1822 Williams, his wife Marianne and their three children embarked on the Lord Sidmouth, a ship carrying women convicts to Port Jackson, New South Wales, Australia.[31] In February 1823, in Hobart, Williams met Samuel Marsden for the first time. In Sydney he met Marsden again and in July 1823 they set sail for New Zealand, accompanying Marsden on his fourth visit to New Zealand on board the Brampton.[32] In 1823 he arrived in the Bay of Islands and settled at Paihia, across the bay from Kororāreka (nowadays Russell); then described as "the hell-hole of the South Pacific" because of the abuse of alcohol and prostitution that was the consequence of the sealing ships and whaling ships that visited Kororāreka.[33]

Early days at Paihia

The members of the Church Missionary Society were under the protection of Hongi Hika, the rangatira (chief) and war leader of the Ngāpuhi iwi (tribe). The immediate protector of the Paihia mission was the chief, Te Koki, and his wife Hamu, a woman of high rank and the owner of the land occupied by the mission at Paihia. Williams was appointed to be the leader of the missionary team. Williams adopted a different approach to missionary work as that applied by Marsden. Marsden's policy had been to teach useful skills rather than focus on religious instruction. This approach had little success in fulfilling the aspirations of the CMS as an evangelistic organisation. Also, in order to obtain essential food, the missionaries had yielded to the pressure to trade in muskets, the item of barter in which Māori showed the greatest interest in order to engage in intertribal warfare during what is known as the Musket Wars.

Williams concentrated on the salvation of souls.[29] The first baptism occurred in 1825, although it was another 5 years before the second baptism.[34] Schools were established, which addressed religious instruction, reading and writing and practical skills. Williams also stopped the trade in muskets, although this had the consequence of reducing trade for food as the Māori withheld the supply of food so as to pressure the missionaries to resume the trade in muskets. Eventually the mission began to grow sufficient food for itself. The Māori eventually came to see that the ban on muskets was the only way to bring an end to the tribal wars, but that took some time.[6]

At first there were several conflicts and confrontations with the Ngāpuhi. One of the most severe was the confrontation with the chief Tohitapu on 12 January 1824, which was witnessed by other chiefs.[35][36] The incident began when Tohitapu visited the mission, finding the gate being shut, Tohitapu jumped over the fence. Williams demanded that Tohitapu enter the mission using the gate. Tohitapu was a chief and a tohunga, skilled to the magic known as makutu. Tohitapu was offended by William's demand and began a threatening haka flourishing his mere and taiaha. Williams faced down this challenge. Tohitapu then seized a pot, which he claimed as compensation for hurting his foot in jumping over the fence, whereupon Williams seized the pot from Tohitapu. The incidence continued through the night during which Tohitapu began a karakia, a chant of bewitchment. Williams had no fear of the karakia.[37][38] The next morning Tohitapu and Williams reconciled their differences - Tohitapu remained a supporter of Williams and the mission at Paihia.[39]

This incident and others in which Williams faced down belligerent chiefs, contributed to his growing mana among the Māori by established to the Māori that Williams had a forceful personality, "[a]lthough his capacity to comprehend the indigenous culture was severely constrained by his evangelical Christianity, his obduracy was in some ways an advantage in dealings with the Maori. From the time of his arrival he refused to be intimidated by the threats and boisterous actions of utu[40] and muru[41] plundering parties".[42]

Kororāreka (Russell) was a provisioning station for whalers and sealers operating in the South Pacific. Apart from the CMS missionaries, the Europeans in the Bay of Islands were largely involved in servicing the trade at Kororāreka. On one occasion escaped convicts arrived in the Bay of Islands. On the morning of 5 January 1827 a brig had arrived, the Wellington, a convict ship from Sydney bound for Norfolk Island. The convicts had risen, making prisoners of the captain, crew, guard and passengers. Williams convinced the captains of two whalers in the harbour to fire into and retake the Wellington. Forty convicts escaped.[43] Threats were made to shoot Williams, whom the convicts considered instrumental in their capture.[44]

Building of the schooner Herald

In 1826 the 55 ton schooner Herald was constructed on the beach at Paihia.[29] Williams was assisted by Gilbert Mair who became the captain of the Herald with William Gilbert Puckey as the mate.[14] This ship enabled Williams the better to provision the mission stations and to more easily visit the more remote areas of New Zealand. One of the first trips of the Herald brought Williams to Port Jackson, Australia. Here he joined his younger brother William and his wife Jane. William, who had studied as a surgeon, had decided to become a missionary in New Zealand. They sailed to Paihia on board the Sir George Osborne, the same ship that brought William and Jane from England.[45]

The Herald was wrecked in 1828 while trying to enter Hokianga Harbour.[46]

Translation of the Bible and dictionary making

The first book published in Te Reo (the Māori language) was A Korao no New Zealand! The New Zealanders First Book!, published by Thomas Kendall in 1815. Kendall travelled to London in 1820 with Hongi Hika and Waikato (a lower ranking Ngāpuhi chief) during which time work was done with Professor Samuel Lee at Cambridge University, which resulted in the First Grammar and Vocabulary of the New Zealand Language (1820).[47] The CMS missionaries did not have a high regard for this book. Williams organised the CMS missionaries into a systematic study of the language and soon started translating the Bible into Māori.[48][49]

After 1826 William Williams became involved in the translation of the Bible and other Christian literature, with Henry Williams devoting more time to his efforts to establish CMS missions in the Waikato, Rotorua and Bay of Plenty. After 1844 Robert Maunsell worked with William Williams on the translation of the Bible.[50] William Williams concentrated on the New Testament; Maunsell worked on the Old Testament, portions of which were published in 1827, 1833 and 1840 with the full translation completed in 1857.[14][51] In July 1827 William Colenso printed the first Māori Bible, comprising three chapters of Genesis, the 20th chapter of Exodus, the first chapter of the Gospel of St John, 30 verses of the fifth chapter of the Gospel of St Matthew, the Lord’s Prayer and some hymns.[52][53]

William Gilbert Puckey also collaborating with William Williams on the translation of the New Testament, which was published in 1837 and its revision in 1844.[14] William Williams published the Dictionary of the New Zealand Language and a Concise Grammar in 1844.

Musket Wars

In the early years of the CMS mission there were incidents of intertribal warfare. In 1827 Hongi Hika, the paramount Ngāpuhi chief, instigated fighting with the tribes to the north of the Bay of Islands. In January 1827 Hongi Hika was accidentally shot in the chest by one of his own warriors.[54] On 6 March 1828 Hongi Hika died at Whangaroa.[55] Williams was active in promoting a peaceful solution in what threatened to be a bloody war. The death of Tiki, a son of Whetoi (Pomare I)[56] and the subsequent death of Te Whareumu in 1828 threw the Hokianga into a state of uncertainty as the other Ngāpuhi chiefs debated whether revenge was necessary following the death of a chief. Williams was asked to mediate between the combatants.[57] As the chiefs did not want to escalate the fighting, a peaceful resolution was achieved.[58]

In 1830 there was a battle at Kororāreka, which is sometimes called the Girls' War,[59] which led to the death of the Ngāpuhi leader Hengi. Williams and Ngāpuhi chiefs, including Tohitapu, attempted to bring an end to the conflict. When the highly respected Samuel Marsden arrived on a visit, he and Williams attempted to negotiate a settlement in which Kororāreka would be ceded by Pomare II as compensation for Hengi's death, which was accepted by those engaged in the fighting.[60] However the duty of seeking revenge had passed to Mango and Kakaha, the sons of Hengi, they took the view that the death of their father should be acknowledged through a muru,[41] or war expedition against tribes to the south. It was accepted practice to conduct a muru against tribes who had no involvement in the events that caused the death of an important chief.[60]

Mango and Kakaha did not commence the muru until January 1832.[61] Willams accompanied the first expedition, without necessarily believing that he could end the fighting, but with the intention of continuing to persuade the combatants as to the Christian message of peace and goodwill. The journal of Henry Williams provides an extensive account of this expedition, which can be described as an incident in the so-called Musket Wars. In this expedition Mango and Kakaha were successful in fights on the Mercury Islands and Tauranga, with the muru lasted until late July 1832.[61] When Williams sailed back to Paihia from Tauranga the boat was caught in a raging sea. Williams took command out of the hands of the captain and saved the ship.[62] By 1844 the conversion of Ngāpuhi chiefs contributed to a significant reduction in the number of incidents of intertribal warfare in the north.[63]

The first conversions of Māori chiefs to Christianity

The first baptism occurred in 1825.[34] On 7 February 1830 Rawiri Taiwhanga, a Ngāpuhi chief, was baptised.[64] He was the first high-ranking Māori to be converted to Christianity.[65] This gave the missionary work of the CMS a great impetus, as it influenced many others to do the same. Hone Heke attended the CMS mission school at Kerikeri in 1824 and 1825. Heke and his wife Ono were baptised on 9 August 1835 and Heke later became a lay reader in the Anglican church. For a time Heke lived at Paihia during which time Williams became a close friend and adviser.[42] In January 1844 Williams baptised Waikato, the Ngāpuhi chief who had travelled to England with Hongi Hika in 1820.[66]

Expansion of the activities of the CMS mission

Williams played a leading role in the expansion of the activities of the CMS. In 1833 a mission was established at Kaitaia in Northland as well as a mission at Puriri in the Thames area. In 1835 missions were established in the Bay of Plenty and Waikato regions at Tauranga, Matamata and Rotorua and in 1836 a mission was open in the Manakau area.

In April 1833, 7 Ngāti Porou men and 5 women arrived in the Bay of Island on the whaler Elizabeth. They had been made prisoner when the Captain of the whaler left Waiapu after a confrontation with the people of that place. In the Bay of Islands they were delivered to Ngāpuhi chiefs to become slaves. Henry Williams, William Williams and Alfred Nesbit Brown persuaded the Ngāpuhi to give up the slaves. An attempt was made to return them on the schooner Active although a gale defeated that attempt. They returned to the Bay of Islands, where they received religious instruction, until the following summer.[67] In January 1834 the schooner Fortitude carried William Williams and the Ngāti Porou to the East Cape.[42][67]

In 1839 Williams travelled by ship to Port Nicholson, Wellington, then by foot to Otaki with the Rev. Octavius Hadfield, where Hadfield established a mission station. From December 1839 to January 1840 Williams returned over land through Whanganui, Taupo, Rotorua, and Tauranga, the first European who had undertaken that journey.[68]

"From 1830 to 1840 Henry Williams ruled the mission with a kind but firm hand.(...) And when the first settlers of the New Zealand Company landed at Wellington in 1839, Williams did his best to repel them, because he felt they would overrun the country, taking the land and teaching the Māori godless customs".[6]

Attempts to interfere with land purchasing by the New Zealand Company

In November 1839 Williams and Octavius Hadfield arrived in Port Nicholson, Wellington, days after the New Zealand Company purchased the land around Wellington harbour. Within months the company purported to purchase approximately 20 million acres (8 million hectares) in Nelson, Wellington, Whanganui and Taranaki. Williams attempted to interfere with the land purchasing practices of the company. Reihana, a Christian who had spent time in the Bay of Islands, had bought for himself 60 acres (24 hectares) of land in Te Aro, in what is now central Wellington. When Reihana and his wife decided to go and live in Taranaki, Williams persuaded Reihana to pass the land to him to hold in trust for Reihana.[69] On his journey north, Williams records in a letter to his wife, “I have secured a piece of land, I trust, from the paws of the New Zealand Company, for the natives; another piece I hope I have upset.”[70] Upon arriving in Whanganui, Williams records, “After breakfast, held council with the chiefs respecting their land, as they were in considerable alarm lest the Europeans should take possession of the county. All approve of their land being purchased and held in trust for their benefit alone.”[71]

The Church Missionary Society in London rejected Williams' request for support for this practice of acquiring land on trust for the benefit of the Māori. The society were well aware that the company actively campaigned against those that opposed it plans. While the Church Missionary Society had connections with the Whig Government of Viscount Melbourne, in August 1841 a Tory government came to office. The Church Missionary Society did not want to be in direct conflict with the New Zealand Company as its leaders had influence within the Tory government led by Sir Robert Peel.

Treaty of Waitangi

Williams played an important role in the translation of the Treaty of Waitangi (1840). In August 1839 Captain William Hobson was given instructions by the Colonial Office to take the constitutional steps needed to establish a British colony in New Zealand. Hobson was sworn in as Lieutenant-Governor in Sydney on 14 January, finally arriving in the Bay of Islands on 29 January 1840. The Colonial Office did not provide Hobson was draft treaty so that he was forced to write his own treaty with the help of his secretary, James Freeman, and British Resident James Busby.[72] The entire treaty was prepared in four days.[73] Realising that a treaty in English could be neither understood, debated or agreed to by Māori, Hobson instructed Williams, who worked with his son Edward, who was also proficient in the Māori language (Te Reo), to translate the document into Māori and this was done overnight on 4 February.[74][75] At this time William Williams, who was also proficient in Te Reo, was in Poverty Bay.

On 5 February 1840 the original English version of the treaty and its translation into Māori were put before a gathering of northern chiefs inside a large marquee on the lawn in front of Busby's house at Waitangi. Hobson read the treaty aloud in English and Williams read his Māori version.[21][74] In his translation he used a dialect known as "Missionary Māori", which was not traditional Māori, but had been made up by the missionaries. An example of this in the Treaty is kāwanatanga (governorship), a cognate word which Williams is believed to have transplanted from English. The word kāwanatanga was first used in the Declaration of Independence of New Zealand (1835).[76] It reappeared in 1840 in the Treaty and hence, some argue, was an inappropriate choice. There is considerable debate about what would have been a more appropriate term. Some scholars argue that mana (prestige, authority) would have more accurately conveyed the transfer of sovereignty;[77] although others argue that mana cannot be given away and is not the same thing as sovereignty.[78]

Hone Heke signed the Treaty of Waitangi although there is uncertainty as to whether he signed it on 6 May 1840 or only signed at a later date after being persuaded to sign by other Māori.[79] In any event he was later to cut down the flagstaff on Flagstaff Hill Kororāreka (nowadays Russell) to express his dissatisfaction with how the representatives of Crown subsequently treated the authority of the chiefs as being subservient to that of the Crown.[42]

Williams was also involved in explaining the treaty to Māori leaders, firstly at the meetings with William Hobson at Waitangi, but later also when he travelled to Port Nicholson, Queen Charlotte's Sound, Kapiti, Waikanae and Otaki to persuade Māori chiefs to sign the treaty.[80] His involvement in these debates brought him "into the increasingly uncomfortable role of mediating between two races".[42]

Controversy over land purchases

In the 1830s Williams purchased 11,000 acres (5,420 hectares) from Te Morenga of Pakaraka in the Tai-a-mai district, inland from the Bay of Islands,[81][82] to provide employment and financial security for his six sons and five daughters as the Church Missionary Society had no arrangements for pensions or other maintenance of CMS missionaries and their families who lived in New Zealand.[15] The Church Missionary Society implemented land purchase policies for its missionaries in Australia, which involved the society paying for the purchase of land for the children of missionaries, but discussions for such a policy for the New Zealand missions had not been settled.

The purchase of the land was reviewed by Land Commissioner FitzGerald under the Land Claims Ordinance 1841. FitzGerald, in the Land Office report of 14 July 1844, recommended that Governor FitzRoy confirm the award in favour of Williams of 9,000 of the 11,000 acres as Williams "appears to have paid on behalf of himself and children enough to entitle them to (22,131) twenty-two thousand one hundred and thirty-one acres".[83] This did not end the controversy over the purchase of land by Williams as the New Zealand Company, and others with an interest in acquiring Māori land, continued to attack the character of Williams.[15] These land purchases were used by the notorious John Dunmore Lang, of New South Wales, as a theme for a virulent attack on the CMS mission in New Zealand in the second of four "Letters To the Right Hon. Earl Durham" that were published in England.[84][85] Lord Durham was a supporter of the New Zealand Company.

Hone Heke and the Flagstaff War

In 1845 George Grey arrived in New Zealand to take up his appointment as Governor. At this time Hone Heke challenged the authority of the British, beginning by cutting down the flagstaff on Flagstaff Hill at Kororāreka. On this flagstaff the flag of the United Tribes of New Zealand had previously flown, now the Union Jack was hoisted; hence the flagstaff symbolised the grievances of Heke and his allies as to changes that had followed the signing of the Treaty of Waitangi.

After the battle of Te Ahuahu Heke went to Kaikohe to recover from his wounds. He was visited by Williams and Robert Burrows, who hoped to persuade Heke to end the fighting.[86] During the Flagstaff War Williams also wrote letters to Hone Heke in further attempts to persuade Heke and Kawiti to cease the conflict.[42] In 1846, following the battles at Ohaeawai pā and Ruapekapeka pā,[87] Hone Heke and Te Ruki Kawiti sought to end the Flagstaff War; with Tāmati Wāka Nene acting as an intermediary, they agreed peace terms with Governor Grey.

Dismissed from service with the CMS

In following years Governor Grey listened to the voices speaking against the CMS missionaries and Grey accused Williams and the other CMS missionaries of being responsible for the Flagstaff War;[88] The newspaper New Zealander of 31 January 1846 inflamed the attack in an article referring to "Treasonable letters. Among the recent proclamations in the Government Gazette of the 24th instant, is one respecting some letters found in the pa at Ruapekapeka, and stating that his Excellency, although aware that they were of a treasonable nature, ordered them to be consigned to the flames, without either perusing or allowing a copy of them to be taken."[83] In a thinly disguised reference to Williams, with the reference to "their Rangatira pakeha [gentlemen] correspondents",[83] the New Zealander went on to state: "We consider these English traitors far more guilty and deserving of severe punishment, than the brave natives whom they have advised and misled. Cowards and knaves in the full sense of the terms, they have pursued their traitorous schemes, afraid to risk their own persons, yet artfully sacrificing others for their own aggrandizement, while, probably at the same time, they were most hypocritically professing most zealous loyalty."[83]

Official communications also blamed the missionaries for the Flagstaff War. In a letter of 25 June 1846 to William Ewart Gladstone, the Colonial Secretary in Sir Robert Peel's government, Governor Grey referred to the land acquired by the CMS missionaries and commented that "Her Majesty's Government may also rest satisfied that these individuals cannot be put in possession of these tracts of land without a large expenditure of British blood and money.”[83][89] Hone Heke, who was born at Pakaraka, the location of the land Williams had purchased. Heke took no action against the CMS missionaries during the war and directed his protest at the representatives of the Crown with Hone Heke and Te Ruki Kawiti fighting the British soldiers and the Ngāpuhi led by Tāmati Wāka Nene who remained loyal to the Crown.[42]

In 1847 William Williams published a pamphlet that defended the role of the Church Missionary Society in the years leading up to the war in the north.[90] The first Anglican bishop of New Zealand, George Augustus Selwyn, took the side of Grey in relation to the purchase of the land[83] and in 1849 the CMS decided to dismiss Williams from service when he refused to give up the land acquired for his family at Pakaraka.[91]

Retirement at Pakaraka and reinstatement to the CMS

Williams and his wife moved to Pakaraka where his children were farming the land that was the source of his troubles. He continued to minister and preach in Holy Trinity Church in Pakaraka, which was built by his family and lived by the church, in a house known as "The Retreat", which still stands.[92]

Governor Grey’s first term of office ended in 1853. In 1854 Williams was reinstated to CMS after Bishop Selwyn and George Grey addressed the committee of the CMS and requested his reinstatement.[42][83][93] Sir George Grey returned to New Zealand in 1861 as Governor. Williams welcomed his return, meeting Grey at the Waimate Mission Station in November 1861.[94]

Williams died on 16 July 1867 and was buried in the grounds of Holy Trinity Church in Pakaraka.

Gallery

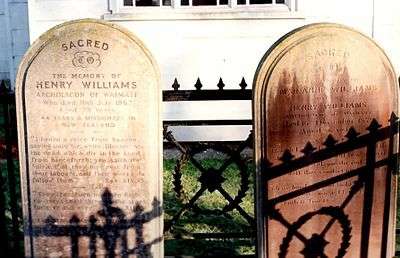

Holy Trinity Church, Pakaraka

Holy Trinity Church, Pakaraka Gravestones of Henry and Marianne Williams, Holy Trinity Church, Pakaraka

Gravestones of Henry and Marianne Williams, Holy Trinity Church, Pakaraka Interior of Holy Trinity Church, Pakaraka

Interior of Holy Trinity Church, Pakaraka A plaque in Holy Trinity Church, Pakaraka

A plaque in Holy Trinity Church, Pakaraka

Notes

- Footnotes

- Citations

- ↑ Fitzgerald, Caroline (2011). Te Wiremu: Henry Williams – Early Years in the North. Huia Publishers, New Zealand. p. xii. ISBN 978-1-86969-439-5.

- ↑ Gillies 1998, p. XI.

- ↑ "Williams, Thomas (?-c.1770)". Dr Williams’s Centre for Dissenting Studies. 2011. Retrieved 21 December 2013.

- ↑ Daniels, Eilir (2010). "Research Report: Rev. Thomas Williams, Gosport, Hampshire (1724/25-1770)". Retrieved 21 December 2013.

- 1 2 Harvey-Williams, Nevil (March 2011). "The Williams Family in the 18th and 19th Centuries - Part 1". Retrieved 21 December 2013.

- 1 2 3 Mitcalfe 1963, p. 34.

- ↑ "Williams, Edward Marsh 1818–1909". Early New Zealand Books (NZETC). 1952. Retrieved 8 April 2012.

- ↑ Evans 1992, p. 21.

- 1 2 3 Harvey-Williams, Nevil (March 2011). "The Williams Family in the 18th and 19th Centuries - Part 2". Retrieved 21 December 2013.

- ↑ Gillies 1998, p. 18.

- ↑ Evans 1992, p. 15

- 1 2 The London Gazette: no. 16540. pp. 2185–2192. 12 November 1811.

- ↑ The London Gazette: no. 20939. p. 244. 26 January 1849.

- 1 2 3 4 Rogers, Lawrence M. (1973). Te Wiremu: A Biography of Henry Williams. Pegasus Press.

- 1 2 3 Carleton 1874, pp. 13–14.

- ↑ Henry Williams in Te Ara Encyclopedia of New Zealand.

- 1 2 Gillies 1998, p. 8.

- 1 2 Harvey-Williams, Nevil (March 2011). "The Williams Family in the 18th and 19th Centuries - Part 3". Retrieved 21 December 2013.

- ↑ "Williams, Henry, 1792-1867 - Homes and haunts - Drawings, New Zealand". Archive of Auckland War Memorial Museum. Retrieved 21 December 2013.

- ↑ Evans 1992, p. 19

- 1 2 "Williams, Edward Marsh 1818–1909". Early New Zealand Books (NZETC). 1952. Retrieved 8 April 2012.

- ↑ "Widow of the Missionary". New Zealand Herald, Volume LVI, Issue 17332, 2 December 1919, Page 8. National Library of NZ. Retrieved 18 October 2015.

- ↑ Boyd, Mary (1 September 2010). "Williams, Samuel - Biography". Dictionary of New Zealand Biography. Te Ara - the Encyclopedia of New Zealand. Retrieved 17 March 2012.

- ↑ Cyclopedia Company Limited (1902). "The Hon. Henry Williams". The Cyclopedia of New Zealand : Auckland Provincial District. Christchurch: The Cyclopedia of New Zealand. Retrieved 1 October 2012.

- ↑ THE TURANGA JOURNALS, 1840-1850: Letters and Journals of William and Jane Williams

- ↑ Mennell, Philip (1892). "

Carleton, Hugh Francis". The Dictionary of Australasian Biography. London: Hutchinson & Co. Wikisource

Carleton, Hugh Francis". The Dictionary of Australasian Biography. London: Hutchinson & Co. Wikisource - ↑ "From about 1816 he (Henry Williams) came under the tutelage of his evangelical brother-in-law, Edward Marsh". biography of Henry Williams

- ↑ Carleton, Hugh (1874). "Vol. I". The Life of Henry Williams. Early New Zealand Books (ENZB), University of Auckland Library.

- 1 2 3 "Henry Williams" (RTF). The Anglican Church in Aotearoa.

- ↑ Carleton 1874, p. 18.

- ↑ Robert Espie (Surgeon). "Surgeon's Journal of Her Majesty's Female Convict Ship Lord Sidmouth (22 August 1822-1 March 1823)" (PDF). (Adm. 101/44/10. Retrieved 14 March 2015.

- ↑ Carleton 1874, pp. 91–123.

- ↑ Wolfe, Richard (2005). Hellhole of the Pacific. Penguin Books (NZ). ISBN 0143019872.

- 1 2 "The Church Missionary Gleaner, April 1874". The New Zealand Mission. Adam Matthew Digital. Retrieved 24 October 2015. (subscription required (help)).

- ↑ Williams, GE (2001). "The Trail of Waitangi: Tohitapu and a Touch of Mäkutu". Early New Zealand History: Covering the Introduction of Civilization, the Gospel, Treaty etc. to New Zealand. Retrieved 2 March 2009.

- ↑ Gillies 1998, pp. 9f.

- ↑ Journal of Marianne Williams, quoted by Carleton1874, pp 39-43

- ↑ Fitzgerald, Caroline (2004). Marianne Williams: Letters from the Bay of Islands. Penguin Books, New Zealand. pp. 72–78. ISBN 0-14-301929-5.

- ↑ Fitzgerald 2004, p. 94 (letter of 7 October 1824)

- ↑ "Traditional Maori Concepts, Utu" Ministry of Justice website

- 1 2 "Traditional Maori Concepts, Muru" Ministry of Justice website

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 Fisher, Robin. "Williams, Henry". Dictionary of New Zealand Biography. Ministry for Culture and Heritage. Retrieved 28 October 2013.

- ↑ Gillies 1995, p. 29-34

- ↑ Fitzgerald 2004, p. 125

- ↑ Gillies 1995, p. 24

- ↑ Evans 1992, p. 21. The schooner is depicted on the 5 cent New Zealand stamp of 1975. See also: Crosby 2004, p. 27

- ↑ Rogers, Lawrence M., (1973) Te Wiremu: A Biography of Henry Williams, Pegasus Press, p. 35, f/n 7 & 39

- ↑ Fitzgerald, Caroline (2011) Letter of Henry Williams, 9 February 1824

- ↑ Fitzgerald, Caroline (2004) Journal of Henry Williams, 12 July 1826

- ↑ Williams, William (1974). The Turanga journals, 1840–1850. F. Porter (Ed) Wellington,. p. 44.

- ↑ Transcribed by the Right Reverend Dr. Terry Brown Bishop of Malaita, Church of the Province of Melanesia, 2008 (10 November 1858). "Untitled article on Maori Bible translation". The Church Journal, New-York. Retrieved 30 November 2014.

- ↑ Gillies 1995, p. 48

- ↑ Rogers 1973, p. 25, f/n, p. 70

- ↑ Journal of William Williams, 1 March 1827 (Caroline Fitzgerald, 2011)

- ↑ Journal of James Stack, Wesleyan missionary, 12 March 1828 (Caroline Fitzgerald, 2011)

- ↑ Ballara, Angela (30 October 2012). "Pomare I". Dictionary of New Zealand Biography. Te Ara - the Encyclopedia of New Zealand. Retrieved 4 March 2014.

- ↑ Fitzgerald, Caroline (2004). "Journal of Marianne Williams, (17 March 1828)". Marianne Williams: Letters from the Bay of Islands. Penguin Books, New Zealand. p. 101. ISBN 0-14-301929-5.

- ↑ Fitzgerald, Caroline (2011). "Journals of Henry Williams, Marianne Williams & William Williams, (16–28 March 1828)". Te Wiremu: Henry Williams – Early Years in the North. Huia Publishers, New Zealand. pp. 101–107. ISBN 978-1-86969-439-5.

- ↑ Smith, S. Percy – Maori Wars of the Nineteenth Century. Christchurch 1910. online at NZETC

- 1 2 Carleton, Hugh (1874). "Vol. I". The Life of Henry Williams. Early New Zealand Books (ENZB), University of Auckland Library. pp. 78–87.

- 1 2 Carleton, Hugh (1874). "Vol. I". The Life of Henry Williams. Early New Zealand Books (ENZB), University of Auckland Library. pp. 106–126.

- ↑ Gillies 1995, p. 35 – 44 and see also Williams 1867, p. 109 - 111

- ↑ Davies, Charles P. "The Church Missionary Gleaner, May 1845". Contrast of Christian and Heathen New Zealanders. Adam Matthew Digital. Retrieved 13 October 2015. (subscription required (help)).

- ↑ Orange, Claudia & Ormond Wilson. 'Taiwhanga, Rawiri fl. 1818 – 1874'. in: Dictionary of New Zealand Biography, updated 22 June 2007

- ↑ Missionary Impact > 'A high profile conversion' by Museum of New Zealand Te Papa Tongarewa

- ↑ King, John. "The Church Missionary Gleaner, April 1845". Baptism of Waikato, a New-Zealand Chief. Adam Matthew Digital. Retrieved 13 October 2015. (subscription required (help)).

- 1 2 Williams, William (1974). The Turanga journals, 1840–1850. F. Porter (Ed). p. 55.

- ↑ Carleton, Hugh (1874). "Vol. II". The Life of Henry Williams. Early New Zealand Books (ENZB), University of Auckland Library. p. 11.

- ↑ Caroline Fitzgerald (2011). Te Wiremu - Henry Williams: Early Years in the North. Huia Press. ISBN 978-1-86969-439-5. Henry Williams Journal (Fitzgerald, pages 290-291)

- ↑ Caroline Fitzgerald (2011). Te Wiremu - Henry Williams: Early Years in the North. Huia Press. ISBN 978-1-86969-439-5. Letter Henry to Marianne, 6 December 1839

- ↑ Caroline Fitzgerald (2011). Te Wiremu - Henry Williams: Early Years in the North. Huia Press. ISBN 978-1-86969-439-5. Henry Williams Journal 16 December 1839 (Fitzgerald, p. 302)

- ↑ "Paul Moon: Hope for watershed in new Treaty era". The New Zealand Herald. 13 January 2010. Retrieved 15 January 2010.

- ↑ Michael King (2003). The Penguin History of New Zealand. Penguin Books. ISBN 0-14-301867-1.

- 1 2 Carleton, Hugh (1874). "Vol. II". The Life of Henry Williams: "Early Recollections" written by Henry Williams. Early New Zealand Books (ENZB), University of Auckland Library. pp. 11–15.

- ↑ Morag McDowell; Duncan Webb. The New Zealand Legal System. LexisNexis. pp. 174–175.

- ↑ "The Declaration of Independence". NZ History Online.

- ↑ Ross, R. M. (1972), "Te Tiriti o Waitangi: Texts and Translations", New Zealand Journal of History 6 (2): 139–141

- ↑ Binney, Judith (1989), "The Maori and the Signing of the Treaty of Waitangi", Towards 1990: Seven Leading Historians Examine Significant Aspects of New Zealand History, pp. 20–31

- ↑ Moon, Paul (2001). Hone Heke: Nga Puhi Warrior. Auckland: David Ling Publishing. ISBN 0-908990-76-6.

- ↑ Carleton, Hugh (1874). "Vol. II". The Life of Henry Williams: "Early Recollections" written by Henry Williams. Early New Zealand Books (ENZB), University of Auckland Library. pp. 15–17.

- ↑ Foster, Bernard John (1966). "Te Morenga (C. 1760–1834)". An Encyclopaedia of New Zealand. Retrieved 18 August 2010.

- ↑ Fitzgerald, Caroline (2011) Letters of Henry Williams to Edward Marsh, 23 September 1833 and 14 February 1834

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 Carleton, Hugh (1874). "Appendix to Vol. II.". The Life of Henry Williams. Early New Zealand Books University of Auckland Library.

- ↑ "John Dunmore Lang - On the Character and Influence of the Missions Hitherto Established in New Zealand, as Regards the Aborigines". Letter II, The Pamphlet Collection of Sir Robert Stout: Volume 29 Early New Zealand Books (NZETC). June 1839. Retrieved 19 October 2013.

- ↑ Carleton, Hugh (1874). "Vol. II". The Life of Henry Williams: Letter: Turanga, April 14, 184, Henry Williams to the Reverend E. G. Marsh. Early New Zealand Books (ENZB), University of Auckland Library. pp. 24–25.

- ↑ "Puketutu and Te Ahuahu - Northern War". Ministry for Culture and Heritage - NZ History online. 3 April 2009. Retrieved 1 April 2012.

- ↑ Reverend Robert Burrows (1886). "Extracts from a Diary during Heke's War in the North in 1845".

- ↑ Rogers, Lawrence M., (1973) Te Wiremu: A Biography of Henry Williams, Pegasus Press, pp. 218-282

- ↑ Sinclair, Keith (7 April 2006). "Grey, George 1812–1898". Dictionary of New Zealand Biography. Retrieved 14 September 2011.

- ↑ The Revd. William Williams (1847). Plain facts about the war in the north. Online publisher – State Library Victoria, Australia: Philip Kunst, Shortland Street, Auckland. Retrieved 21 May 2016.

- ↑ Mitcalfe 1963, p. 35

- ↑ Henry and William Williams Memorial Museum Trust

- ↑ Rogers 1973, p. 190

- ↑ Rogers 1973, pp. 299-300

Literature and sources

- (English) Rogers, Lawrence M. (editor) (1961) - The Early Journals of Henry Williams 1826 to 1840. Christchurch : Pegasus Press. online available at New Zealand Electronic Text Centre (NZETC) (2011-06-27)

- (English) Carleton, Hugh (1874) - The life of Henry Williams, Archdeacon of Waimate. Auckland NZ. Online available from Early New Zealand Books (ENZB).

- (English) Crosby, Ron (2004) - Gilbert Mair, Te Kooti's Nemesis. Reed Publ. Auckland NZ. ISBN 0-7900-0969-2

- (English) Evans, Rex D. (compiler) (1992) - Faith and farming Te huarahi ki te ora; The Legacy of Henry Williams and William Williams. Published by Evagean Publishing, 266 Shaw Road, Titirangi, Auckland NZ. ISBN 0-908951-16-7 (soft cover), ISBN 0-908951-17-5 (hard cover), ISBN 0-908951-18-3 (leather bound)

- (English) Fitzgerald, Caroline (2011) - Te Wiremu - Henry Williams: Early Years in the North, Huia Publishers, New Zealand ISBN 978-1-86969-439-5

- (English) Fitzgerald, Caroline (2004) - Letters from the Bay of Islands, Sutton Publishing Limited, United Kingdom; ISBN 0-7509-3696-7 (Hardcover). Penguin Books, New Zealand, (Paperback) ISBN 0-14-301929-5

- (English) Gillies, Iain and John (1998) - East Coast Pioneers. A Williams Family Portrait; A Legacy of Land, Love and Partnership. Published by The Gisborne Herald Co. Ltd, Gladstone Road, Gisborne NZ. ISBN 0-473-05118-4

- (English) Mitcalfe, Barry (1963) - Nine New Zealanders. Christchurch NZ. The chapter 'Angry peacemaker: Henry Williams – A missionary's courage wins Maori converts' (p. 32 - 36)

- (English) Fisher, Robin (2007) - Williams, Henry 1792 - 1867 in Dictionary of New Zealand Biography (DNZB), updated 22 June 2007

- (English) Rogers, Lawrence M. (1973) - Te Wiremu: A Biography of Henry Williams, Christchurch : Pegasus Press

- (English) Williams, William (1867) - Christianity among the New Zealanders. London. Online available from Archive.org.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to: |

- Henry Williams copy of the Treaty of Waitangi on New Zealand History online.

- Henry Williams biography from the Dictionary of New Zealand Biography

- The Early Journals of Henry Williams; Senior Missionary in New Zealand of the Church Missionary Society (1826–40). Edited by Lawrence M. Rogers. Pegasus Press, Christchurch 1961, at NZETC

- some sketches made by Henry Williams at NZETC

- The Character of Henry Williams described by Hugh Carleton (1874) – The Life of Henry Williams