History of Karachi

| Part of a series on the History of Karachi | |

| |

| Ancient period | |

|---|---|

| Islamic period | |

| Local dynasties | |

| British period | |

| Independent Pakistan | |

|

Federal Capital Territory | |

The area of Karachi (Urdu: تاريخِ ڪراچي ) in Sindh, Pakistan, has a natural harbor and has been used as fishing port by local fisherman belonging to Sindhi tribes since prehistory. The port was known to the ancient Greeks by many names: Krokola, where Alexander the Great camped in Sindh to prepare a fleet for Babylonia after his campaign in the Indus Valley; 'Morontobara' port (probably the modern Manora Island near the Karachi harbor), from where Alexander's admiral Nearchus sailed for back home; and Barbarikon (Βαρβαρικόν), a sea port of the Indo-Greek Bactrian kingdom. Karachi was called Ramya in some Greek texts.[1] The Arabs knew it as the port of Debal, from where Muhammad bin Qasim led his conquering force into Sindh (the western corner of South Asia) in AD 712. According to the British historian Eliot, parts of district of Karachi and the island of Manora constituted the city of Debal. Lahari Bandar or Lari Bandar succeeded Debal as a major port of the Indus[2] it was located close to Banbhore, in modern Karachi.

Early history

The Late Paleolithic and Mesolithic sites found by Karachi University team on the Mulri Hills, in front of Karachi University Campus, constitute one of the most important archaeological discoveries made in Sindh during the last fifty years. The last hunter-gatherers, who left abundant traces of their passage, repeatedly inhabited the Hills. Some twenty different spots of flint tools were discovered during the surface surveys.

Karachi was known to the ancient Greeks by many names: Krokola, the place where Alexander the Great camped to prepare a fleet for Babylonia after his campaign in the Indus Valley; Morontobara (probably Manora island near Karachi harbour), from whence Alexander's admiral Nearchus set sail; and Barbarikon, a port of the Bactrian kingdom. It was later known to the Arabs as Debal from where Muhammad bin Qasim led his conquering force into South Asia in AD 712.[3]

Karachi was reputedly founded as "Kolachi" by Baloch tribes from Balochistan and Makran, who established a small fishing community in the area.[4] Descendants of the original community still live in the area on the small island of Abdullah Goth, which is located near the Karachi Port. The original name "Kolachi" survives in the name of a well-known Karachi locality named Mai Kolachi in Balochi. Mirza Ghazi Beg, the Mughal administrator of Sindh, is among the first historical figures credited for the development of coastal Sindh (consisting of regions such as the Makran coast and the Indus delta), including the cities of Thatta, Bhambore and Karachi. The ancient names of Karachi included: Krokola, Barbarikon, Nawa Nar, Rambagh, Kurruck, Karak Bander, Auranga Bandar, Minnagara, Kolachi, Morontobara, Kolachi-jo-Goth, Banbhore, Debal, Barbarice and Kurrachee.[5][6]

Muslim era

In AD 711, Muhammad bin Qasim conquered the Sindh and Indus Valley, bringing South Asian societies into contact with Islam, succeeding partly because Dahir was an unpopular Hindu king that ruled over a Buddhist majority and that Chach of Alor and his kin were regarded as usurpers of the earlier Buddhist Rai dynasty.[7][8] a view questioned by those who note the diffuse and blurred nature of Hindu and Buddhist practices in the region,[9] especially that of a royalty to be patrons of both and those who believe that Chach himself may have been a Buddhist.[10][11] The forces of Muhammad bin Qasim defeated Raja Dahir in alliance with the Jats and other regional governors.

In the seventeenth century, Karak Bander was a small port on the Arabian Sea on the estuary of the Hub River, 40 km west of present-day Karachi. It was a transit point for the South Asian-Central Asian trade. The estuary silted up due to heavy rains in 1728 and the harbour could no longer be used. As a result, the merchants of Karak Bander decided to relocate their activities to what is today known as Karachi. Trade increased between 1729 and 1839 because of the silting up of Shahbandar and Keti Bandar (important ports on the Indus River) and the shifting of their activities to Karachi.[12]

This settlement was reputedly founded by Baloch tribes from Balochistan and Makran in 1729 as the settlement of Kolachi.[13] According to legend, the city started as a fishing settlement, where a fisherwoman, Mai Kolachi, settled and started a family. The village that grew out of this settlement was known as Kolachi-jo-Goth (The Village of Kolachi in Sindhi). When Sindh started trading across the sea with Muscat and the Persian Gulf in the late 18th century, Karachi gained in importance; a small fort was constructed for its protection with a few cannons imported from Muscat. The fort had two main gateways: one facing the sea, known as Khara Dar (Brackish Gate) and the other facing the adjoining Lyari river, known as the Meetha Dar (Sweet Gate). The location of these gates corresponds to the present-day city localities of Khaaradar (Khārā Dar) and Meethadar (Mīṭhā Dar) respectively. The Soomra dynasty, Samma Dynasty, Arghun Dynasty, Tarkhan and Talpur dynasties ruled Sindh.

During the rule of the Mughal administrator of Sindh, Mirza Ghazi Beg the city was well fortified against Portuguese colonial incursions in Sindh. Debal and the Manora Island and was visited by Ottoman admiral Seydi Ali Reis and mentioned in his book Mir'ât ül Memâlik in 1554. In 1568 Debal was attacked by the Portuguese Admiral Fernão Mendes Pinto in an attempt to capture or destroy the Ottoman vessels anchored there. Fernão Mendes Pinto also claims that Sindhi sailors joined the Ottoman Admiral Kurtoğlu Hızır Reis on his voyage to Aceh. Debal was also visited by the British travel writers such as Thomas Postans and Eliot, who is noted for his vivid account on the city of Thatta. During the reign of the Kalhora dynasty the present city started life as a fishing settlement when a Sindhi Balochi fisher-woman called Mai Kolachi took up residence and started a family. The city was an integral part of the Talpur dynasty in the 1720's.

The name Karachee was used for the first time in a Dutch document from 1742, in which a merchant ship de Ridderkerk is shipwrecked near the original settlement.[14][15] The city continued to be ruled by the Talpur Amir's of Sindh until it was occupied by Bombay Army under the command of John Keane on 2 February 1839.[16]

Talpur period (1795–1839)

In 1795, Kolachi-jo-Goth passed from the control of the Khan of Kalat, Kalat to the Talpur rulers of Sindh. The British, venturing and enterprising in South Asia opened a small factory here in September 1799, but it was closed down within a year because of disputes with the ruling Talpurs. However, this village by the mouth of the Indus river had caught the attention of the British East India Company, who, after sending a couple of exploratory missions to the area, conquered the town on February 3, 1839. In the eighteenth century Karachi was occupied by the Kalhora dynasty, handed over by them to the Khan of Kalat as blood money for the killing of his brother by the Kalhoras, and finally taken over by the Talpur dynasty. In 1838, the British occupied it to use it for launching their campaigns against the Russian Empire in Central Asia and Afghanistan.

Company rule (1839–1858)

After sending a couple of exploratory missions to the area, the British East India Company conquered the town on February 3, 1839. The town was later annexed to the British Indian Empire when Sindh was conquered by Charles James Napier in Battle of Miani on February 17, 1843. Karachi was made the capital of Sindh in the 1840s. On Napier's departure it was added along with the rest of Sindh to the Bombay Presidency, a move that caused considerable resentment among the native Sindhis. The British realised the importance of the city as a military cantonment and as a port for exporting the produce of the Indus River basin, and rapidly developed its harbour for shipping. The foundations of a city municipal government were laid down and infrastructure development was undertaken. New businesses started opening up and the population of the town began rising rapidly.

The arrival of troops of the Kumpany Bahadur in 1839 spawned the foundation of the new section, the military cantonment. The cantonment formed the basis of the 'white' city where the Indians were not allowed free access. The 'white' town was modeled after English industrial parent-cities where work and residential spaces were separated, as were residential from recreational places.

Karachi was divided into two major poles. The 'black' town in the northwest, now enlarged to accommodate the burgeoning Indian mercantile population, comprised the Old Town, Napier Market and Bunder, while the 'white' town in the southeast comprised the Staff lines, Frere Hall, Masonic lodge, Sindh Club, Governor House and the Collectors Kutchery [Law Court] /kəˈtʃɛri/ located in the Civil Lines Quarter. Saddar bazaar area and Empress Market were used by the 'white' population, while the Serai Quarter served the needs of the 'black' town.

The village was later annexed to the British Indian Empire when the Sindh was conquered by Charles Napier in 1843. The capital of Sindh was shifted from Hyderabad to Karachi in the 1840s. This led to a turning point in the city's history. In 1847, on Napier's departure the entire Sindh was added to the Bombay Presidency. The post of the governor was abolished and that of the Chief Commissioner in Sindh established.

The British realized its importance as a military cantonment and a port for the produce of the Indus basin, and rapidly developed its harbor for shipping. The foundation of a city municipal committee was laid down by the Commissioner in Sinde, Bartle Frere and infrastructure development was undertaken. Consequently, new businesses started opening up and the population of the town started rising rapidly. Karachi quickly turned into a city, making true the famous quote by Napier who is known to have said: Would that I could come again to see you in your grandeur!

In 1857, the Indian Mutiny broke out in South Asia and the 21st Native Infantry stationed in Karachi declared allegiance to rebels, joining their cause on 10 September 1857. Nevertheless, the British were able to quickly reassert control over Karachi and defeat the uprising. Karachi was known as Khurachee Scinde (i.e. Karachi, Sindh) during the early British colonial rule.

The British Raj (1858–1947)

In 1795, the village became a domain of the Balochi Talpur rulers. A small factory was opened by the British in September 1799, but was closed down within a year. In 1864, the first telegraphic message was sent from India to England when a direct telegraph connection was laid between Karachi and London.[17] In 1878, the city was connected to the rest of British India by rail. Public building projects such as Frere Hall (1865) and the Empress Market (1890) were undertaken. In 1876, Muhammad Ali Jinnah, the founder of Pakistan, was born in the city, which by now had become a bustling city with Temples, mosques, churches, courthouses, markets, paved streets and a magnificent harbour. By 1899 Karachi had become the largest wheat exporting port in the east.[18] The population of the city was about 105,000 inhabitants by the end of the 19th century, with a cosmopolitan mix of Muslims, Hindus, Europeans, Jews, Parsis, Iranians, Lebanese, and Goans. By around the start of the 20th century, the city faced street congestion, which led to South Asia's first tramway system being laid down in 1900.

The city remained a small fishing village until the British seized control of the offshore and strategically located at Manora Island. Thereafter, authorities of the British Raj embarked on a large-scale modernisation of the city in the 19th century with the intention of establishing a major and modern port which could serve as a gateway to Punjab, the western parts of British Raj, and Afghanistan. The city was predominantly Muslim with Sindhi and Baloch ethnic groups. Britain's competition with imperial Russia during the Great Game also heightened the need for a modern port near Central Asia, and so Karachi prospered as a major centre of commerce and industry during the Raj, attracting communities of: Africans, Arabs, Armenians, Catholics from Goa, Jews, Lebanese, Malays, Konkani people from Maharashtra, Kuchhi from Kuchh, Gujarat in India, and Zoroastrians (also known as Parsees) - in addition to the large number of British businessmen and colonial administrators who established the city's poshest locales, such as Clifton. This mass migration changed the religious and cultural mosaic of Karachi.

British colonialists embarked on a number of public works of sanitation and transportation, such as gravel paved streets, proper drains, street sweepers, and a network of trams and horse-drawn trolleys. Colonial administrators also set up military camps, a European inhabited quarter, and organised marketplaces, of which the Empress Market is most notable. The city's wealthy elite also endowed the city with a large number of grand edifices, such as the elaborately decorated buildings that house social clubs, known as 'Gymkhanas.' Wealthy businessmen also funded the construction of the Jehangir Kothari Parade (a large seaside promenade) and the Frere Hall, in addition to the cinemas, and gambling parlours which dotted the city.

By 1914, Karachi had become the largest grain exporting port of the British Empire. In 1924, an aerodrome was built and Karachi became the main airport of entry into British Raj. An airship mast was also built in Karachi in 1927 as part of the Imperial Airship Communications scheme, which was later abandoned. In 1936, Sindh was separated from the Bombay Presidency and Karachi was made again the capital of the Sindh. In 1947, when Pakistan achieved independence, Karachi had become a bustling metropolitan city with beautiful classical and colonial European styled buildings lining the city's thoroughfares.

As the movement for independence almost reached its conclusion, the city suffered widespread outbreaks of communal violence between the majority Muslims and the minority Hindus, who were often targeted by the incoming Muslim refugees. In response to the perceived threat of Hindu domination, self-preservation of identity, language and culture in combination with Sindhi Muslim resentment towards wealthy Sindhi Hindus, the province of Sindh became the first province of British India to pass the Pakistan Resolution, in favour of the creation of the Pakistani state. The predominantly Muslim population supported Muslim League and Pakistan Movement. After the independence of Pakistan in 1947, the minority Hindus and Sikhs migrated to India and this led to the decline of Karachi, as Hindus controlled the business in Karachi, while the Muslim refugees from India settled down in Karachi. While many poor low caste Hindus, Christians, and wealthy Zoroastrians (Parsees) remained in the city, Karachi's Sindhi Hindu migrated to India and was replaced by Muslim refugees who, in turn, had been uprooted from regions belonging to India.

Pakistan's capital (1947–1958)

Karachi was chosen as the capital city of Pakistan. After the independence of Pakistan, the city population increased dramatically when hundreds of thousands of Muslim Muhajirs from India fleeing from anti-Muslim pograms and from other parts of South Asia came to settle in Karachi.[19] As a consequence, the demographics of the city also changed drastically. The Government of Pakistan through Public Works Department bought land to settle the Muslim refugees.[20] However, it still maintained a great cultural diversity as its new inhabitants arrived from the different parts of the South Asia. In 1959, the capital of Pakistan was shifted from Karachi to Islamabad and Karachi became the capital of Sindh.

Cosmopolitan city (1958–1980)

During the 1960s, Karachi was seen as an economic role model around the world. Many countries sought to emulate Pakistan's economic planning strategy and one of them, South Korea, copied the city's second "Five-Year Plan" and World Financial Centre in Seoul is designed and modeled after Karachi.

The Pakistani presidential election, 1965 disturbance and political movement against President Muhammad Ayub Khan started of a long period of decline in the city. The city's population continued to grow exceeding the capacity of its creaking infrastructure and increased the pressure on the city.

The 1970s saw major labour struggles in Karachi's industrial estates. During the administration of Prime Minister Zulfikar Ali Bhutto riots and Karachi labour unrest of 1972 caused major decline in economic development. During President Muhammad Zia-ul-Haq's martial law, Karachi saw relative peace and prosperity, specially during the 3 years of Major General Mahmood Aslam Hayat, as Deputy Martial Law Administrator Karachi from 1977 to 1980.

Post 1970s (1980–present)

The 1980s and '90s also saw an influx of Afghan refugees from the Soviet war in Afghanistan into Karachi, and the city. Political tensions between the Muhajir and other groups also erupted and the city was wracked with political violence. The period from 1992 to 1994 is regarded as the bloody period in the history of the city, when the Army commenced its Operation Clean-up against the Mohajir Qaumi Movement.

Since the last couple of years however, most of these tensions have largely been quieted. Karachi continues to be an important financial and industrial centre for the Sindh and handles most of the overseas trade of Pakistan and the Central Asian countries. It accounts for a large portion of the GDP of Sindh, Pakistan and a large chunk of the country's white collar workers. Karachi's population has continued to grow and is estimated to have exceeded 15 million people. Currently, Karachi is a melting pot where people from all the different parts of Pakistan live. The Sindh government is undertaking a massive upgrading of the city's infrastructure which promises to again put this heart of Sindh city of Karachi into the lineup of one of the world's greatest metropolitan cities.

The last census was held on 1998, the current estimated population ratio of 2012 is :

Urdu: 41.52% Pashto: 18.96% Punjabi: 15.64% Sindhi: 10.34% Balochi: 06.34% Saraiki: 04.11% Others: 03.09%. The others include Konkani, Kuchhi, Gujarati, Dawoodi Bohra, Memon, Brahui, Makrani, Khowar, Burushaski, Arabic, and Bengali.

Picture gallery

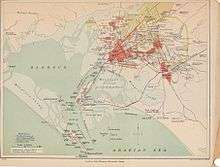

A map of Karachi from 1889

A map of Karachi from 1889 The Empress Market, 1890

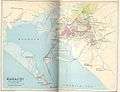

The Empress Market, 1890 A map of Karachi from 1893

A map of Karachi from 1893 View of the dense old native town by the end of the 19th century

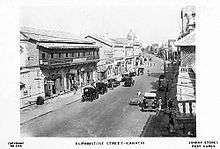

View of the dense old native town by the end of the 19th century View of the Bunder Road (now M. A. Jinnah Rd.), 1900

View of the Bunder Road (now M. A. Jinnah Rd.), 1900 Bunder Road

Bunder Road Farewell arch erected by the Karachi Port for the Royal visit of Prince of Wales, later King George V, 1906

Farewell arch erected by the Karachi Port for the Royal visit of Prince of Wales, later King George V, 1906 British family at Elphinstone St., 1914

British family at Elphinstone St., 1914 Frere Hall, Karachi, c1860.

Frere Hall, Karachi, c1860.

See also

References

- ↑ Infiltration by the gods

- ↑ The Ancient Geography of India

- ↑ Archived September 24, 2013, at the Wayback Machine.

- ↑ "DAWN – Features; August 8, 2002". Dawn.Com. 8 August 2002. Retrieved 10 February 2014.

- ↑ Kurrachee: (Karachi) Past, Present and Future

- ↑ A gazetteer of the province of Sindh

- ↑ Nicholas F. Gier, FROM MONGOLS TO MUGHALS: RELIGIOUS VIOLENCE IN INDIA 9TH-18TH CENTURIES, Presented at the Pacific Northwest Regional Meeting American Academy of Religion, Gonzaga University, May 2006 . Retrieved 11 December 2006.

- ↑ Naik, C.D. (2010). Buddhism and Dalits: Social Philosophy and Traditions. Delhi: Kalpaz Publications. p. 32. ISBN 978-81-7835-792-8.

- ↑ P. 151 Al-Hind, the Making of the Indo-Islamic World By André Wink

- ↑ P. 164 Notes on the religious, moral, and political state of India before the Mahomedan invasion, chiefly founded on the travels of the Chinese Buddhist priest Fai Han in India, A.D. 399, and on the commentaries of Messrs. Remusat, Klaproth, Burnouf, and Landresse, Lieutenant-Colonel W. H. Sykes by Sykes, Colonel;

- ↑ P. 505 The History of India, as Told by Its Own Historians by Henry Miers Elliot, John Dowson

- ↑ The case of Karachi, Pakistan

- ↑ Askari, Sabiah (2015). Studies on Karachi: Papers Presented at the Karachi Conference 2013. Cambridge Scholars Publishing. ISBN 978-1443877442.

- ↑ The Dutch East India Company (VOC) and Diewel-Sind (Pakistan) in the 17th and 18th centuries, Floor, W. Institute of Central & West Asian Studies, University of Karachi, 1993–1994, p. 49.

- ↑ "The Dutch East India Company's shipping between the Netherlands and Asia 1595–1795". Retrieved 14 June 2015.

- ↑ Laurent Gayer 2014, pp. 42.

- ↑ Harris, Christina Phelps (1969). "The Persian Gulf Submarine Telegraph of 1864". The Geographical Journal. 135 (2): 169–90. doi:10.2307/1796823. ISSN 1475-4959. JSTOR 1796823 – via JSTOR. (registration required (help)).

- ↑ Fieldman, Herbert, Karachi through a hundred years, OUP, UK, 1960

- ↑ "Port Qasim | About Karachi". Port Qasim Authority. Retrieved 10 February 2014.

- ↑ A story behind every name

External links

- A story behind every name

- History of Karachi with old & new Pictures

- 'Traitor of Sindh' Seth Naomal: A case of blasphemy in 1832

- The real Father of Karachi (it's not who you think)

- The real Father of Karachi — II

- Of streets and names

- Harchand Rai Vishan Das: Karachi's beheaded benefactor

- Karachi's Polo Ground: Digging into history

- Ranchor Line: 14 acres of an abandoned identity

- Mr. Strachan and Maulana Wafaai

- The Clifton of yore

- Karachi's Ranchor Line: Where red chilli is no more