History of Uzbekistan

In the first millennium BC, Iranian nomads established irrigation systems along the rivers of Central Asia and built towns at Bukhara and Samarqand. These places became extremely wealthy points of transit on what became known as the Silk Road between China and Europe. In the seventh century AD, the Soghdian Iranians, who profited most visibly from this trade, saw their province of Transoxiana (Mawarannahr) overwhelmed by Arabs, who spread Islam throughout the region. Under the Arab Abbasid Caliphate, the eighth and ninth centuries were a golden age of learning and culture in Transoxiana. As Turks began entering the region from the north, they established new states, many of which were Persianate in nature. After a succession of states dominated the region, in the twelfth century, Transoxiana was united in a single state with Iran and the region of Khwarezm, south of the Aral Sea. In the early thirteenth century, that state was invaded by Mongols, led by Genghis Khan. Under his successors, Iranian-speaking communities were displaced from some parts of Central Asia. Under Timur (Tamerlane), Transoxiana began its last cultural flowering, centered in Samarqand. After Timur the state began to split, and by 1510 Uzbek tribes had conquered all of Central Asia.[1]

In the sixteenth century, the Uzbeks established two strong rival khanates, Bukhoro and Khorazm. In this period, the Silk Road cities began to decline as ocean trade flourished. The khanates were isolated by wars with Iran and weakened by attacks from northern nomads. Between 1729 and 1741 all the Khanates were made into vassals by Nader Shah of Persia. In the early nineteenth century, three Uzbek khanates—Bukhoro, Khiva, and Quqon (Kokand)—had a brief period of recovery. However, in the mid-nineteenth century Russia, attracted to the region's commercial potential and especially to its cotton, began the full military conquest of Central Asia. By 1876 Russia had incorporated all three khanates (hence all of present-day Uzbekistan) into its empire, granting the khanates limited autonomy. In the second half of the nineteenth century, the Russian population of Uzbekistan grew and some industrialization occurred.[1]

At the beginning of the twentieth century, the Jadidist movement of educated Central Asians, centered in present-day Uzbekistan, began to advocate overthrowing Russian rule. In 1916 violent opposition broke out in Uzbekistan and elsewhere, in response to the conscription of Central Asians into the Russian army fighting World War I. When the tsar was overthrown in 1917, Jadidists established a short-lived autonomous state at Quqon. After the Bolshevik Party gained power in Moscow, the Jadidists split between supporters of Russian communism and supporters of a widespread uprising that became known as the Basmachi Rebellion. As that revolt was being crushed in the early 1920s, local communist leaders such as Faizulla Khojayev gained power in Uzbekistan. In 1924 the Soviet Union established the Uzbek Soviet Socialist Republic, which included present-day Tajikistan and Uzbekistan. Tajikistan became the separate Tajik Soviet Socialist Republic in 1929. In the late 1920s and early 1930s, large-scale agricultural collectivization resulted in widespread famine in Central Asia. In the late 1930s, Khojayev and the entire leadership of the Uzbek Republic were purged and executed by Soviet leader Joseph V. Stalin (in power 1927–53) and replaced by Russian officials. The Russification of political and economic life in Uzbekistan that began in the 1930s continued through the 1970s. During World War II, Stalin exiled entire national groups from the Caucasus and the Crimea to Uzbekistan to prevent "subversive" activity against the war effort.[1]

Moscow’s control over Uzbekistan weakened in the 1970s as Uzbek party leader Sharaf Rashidov brought many cronies and relatives into positions of power. In the mid-1980s, Moscow attempted to regain control by again purging the entire Uzbek party leadership. However, this move increased Uzbek nationalism, which had long resented Soviet policies such as the imposition of cotton monoculture and the suppression of Islamic traditions. In the late 1980s, the liberalized atmosphere of the Soviet Union under Mikhail S. Gorbachev (in power 1985–91) fostered political opposition groups and open (albeit limited) opposition to Soviet policy in Uzbekistan. In 1989 a series of violent ethnic clashes involving Uzbeks brought the appointment of ethnic Uzbek outsider Islam Karimov as Communist Party chief. When the Supreme Soviet of Uzbekistan reluctantly approved independence from the Soviet Union in 1991, Karimov became president of the Republic of Uzbekistan.[1]

In 1992 Uzbekistan adopted a new constitution, but the main opposition party, Birlik, was banned, and a pattern of media suppression began. In 1995 a national referendum extended Karimov’s term of office from 1997 to 2000. A series of violent incidents in eastern Uzbekistan in 1998 and 1999 intensified government activity against Islamic extremist groups, other forms of opposition, and minorities. In 2000 Karimov was reelected overwhelmingly in an election whose procedures received international criticism. Later that year, Uzbekistan began laying mines along the Tajikistan border, creating a serious new regional issue and intensifying Uzbekistan’s image as a regional hegemon. In the early 2000s, tensions also developed with neighboring states Kyrgyzstan and Turkmenistan. In the mid-2000s, a mutual defense treaty substantially enhanced relations between Russia and Uzbekistan. Tension with Kyrgyzstan increased in 2006 when Uzbekistan demanded extradition of hundreds of refugees who had fled from Andijon into Kyrgyzstan after the riots. A series of border incidents also inflamed tensions with neighboring Tajikistan. In 2006 Karimov continued arbitrary dismissals and shifts of subordinates in the government, including one deputy prime minister.[1]

Prehistory

In 1938 A. Okladnikov discovered the 70,000-year-old skull of an 8- to 11-year-old Neanderthal child in Teshik-Tash in Uzbekistan.[2]

Early history

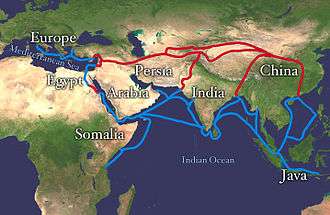

The first people known to have occupied Central Asia were Iranian nomads who arrived from the northern grasslands of what is now Kazakhstan sometime in the first millennium BC. These nomads, who spoke Iranian dialects, settled in Central Asia and began to build an extensive irrigation system along the rivers of the region. At this time, cities such as Bukhoro (Bukhara) and Samarqand (Samarkand) began to appear as centers of government and culture. By the fifth century BC, the Bactrian, Soghdian, and Tokharian states dominated the region. As China began to develop its silk trade with the West, Iranian cities took advantage of this commerce by becoming centers of trade. Using an extensive network of cities and settlements in the province of Transoxiana (Mawarannahr was a name given the region after the Arab conquest) in Uzbekistan and farther east in what is today China's Xinjiang Uygur Autonomous Region, the Soghdian intermediaries became the wealthiest of these Iranian merchants. Because of this trade on what became known as the Silk Route, Bukhoro and Samarqand eventually became extremely wealthy cities, and at times Transoxiana was one of the most influential and powerful Persian provinces of antiquity.[3]

The wealth of Transoxiana was a constant magnet for invasions from the northern steppes and from China. Numerous intraregional wars were fought between Soghdian states and the other states in Transoxiana, and the Persians and the Chinese were in perpetual conflict over the region. Alexander the Great conquered the region in 328 BC, bringing it briefly under the control of his Macedonian Empire.[3]

In the same centuries, however, the region also was an important center of intellectual life and religion. Until the first centuries after Christ, the dominant religion in the region was Zoroastrianism, but Buddhism, Manichaeism, and Christianity also attracted large numbers of followers.[3]

Early Islamic period

The conquest of Central Asia by Muslim Arabs, which was completed in the eighth century AD, brought to the region a new religion that continues to be dominant. The Arabs first invaded Transoxiana in the middle of the seventh century through sporadic raids during their conquest of Persia. Available sources on the Arab conquest suggest that the Soghdians and other Iranian peoples of Central Asia were unable to defend their land against the Arabs because of internal divisions and the lack of strong indigenous leadership. The Arabs, on the other hand, were led by a brilliant general, Qutaybah ibn Muslim, and were also highly motivated by the desire to spread their new faith (the official beginning of which was in AD 622). Because of these factors, the population of Transoxiana was easily subdued. The new religion brought by the Arabs spread gradually into the region. The native religious identities, which in some respects were already being displaced by Persian influences before the Arabs arrived, were further displaced in the ensuing centuries. Nevertheless, the destiny of Central Asia as an Islamic region was firmly established by the Arab victory over the Chinese armies in 750 in a battle at the Talas River.[4]

Despite brief Arab rule, Central Asia successfully retained much of its Iranian characteristic, remaining an important center of culture and trade for centuries after the adoption of the new religion. Transoxiana continued to be an important political player in regional affairs, as it had been under various Persian dynasties. In fact, the Abbasid Caliphate, which ruled the Arab world for five centuries beginning in 750, was established thanks in great part to assistance from Central Asian supporters in their struggle against the then-ruling Umayyad Caliphate.[4]

During the height of the Abbasid Caliphate in the eighth and the ninth centuries, Central Asia and Transoxiana experienced a truly golden age. Bukhoro became one of the leading centers of learning, culture, and art in the Muslim world, its magnificence rivaling contemporaneous cultural centers such as Baghdad, Cairo, and Cordoba. Some of the greatest historians, scientists, and geographers in the history of Islamic culture were natives of the region.[4]

As the Abbasid Caliphate began to weaken and local Islamic Iranian states emerged as the rulers of Iran and Central Asia, the Persian language continued its preeminent role in the region as the language of literature and government. The rulers of the eastern section of Iran and of Transoxiana were Persians. Under the Samanids and the Buyids, the rich Perso-Islamic culture of Transoxiana continued to flourish.[4]

Turkification of Transoxiana

In the ninth century, the continued influx of nomads from the northern steppes brought a new group of people into Central Asia. These people were the Turks who lived in the great grasslands stretching from Mongolia to the Caspian Sea. Introduced mainly as slave soldiers to the Samanid Dynasty, these Turks served in the armies of all the states of the region, including the Abbasid army. In the late tenth century, as the Samanids began to lose control of Transoxiana (Mawarannahr) and northeastern Iran, some of these soldiers came to positions of power in the government of the region, and eventually established their own states, albeit highly Persianized. With the emergence of a Turkic ruling group in the region, other Turkic tribes began to migrate to Transoxiana.[5]

The first of the Turkic states in the region was the Persianate Ghaznavid Empire, established in the last years of the tenth century. The Ghaznavid state, which captured the Samanid domains south of the Amu Darya, was able to conquer large areas of eastern Iran, Central Asia, Afghanistan, and Pakistan during the reign of Sultan Mahmud. The Ghaznavids were closely followed by the Turkic Qarakhanids, who took the Samanid capital Bukhara in 999 AD, and ruled Transoxiana for the next two centuries. Samarkand was made the capital of the Western Qarakhanid state.[6]

The dominance of Ghazna was curtailed, however, when the Seljuks led themselves into the western part of the region, conquering the Ghaznavid territory of Khorazm (also spelled Khorezm and Khwarazm).[5] The Seljuks also defeated the Karakhanids, but did not annex their territories outright. Instead they made the Karakhanids a vassal state.[7] The Seljuks dominated a wide area from Asia Minor, Iran, Iraq, and parts of the Caucasus, to the western sections of Transoxiana, in Afghanistan, in the eleventh century. The Seljuk Empire then split into states ruled by various local Turkic and Iranian rulers. The culture and intellectual life of the region continued unaffected by such political changes, however. Turkic tribes from the north continued to migrate into the region during this period.[5] The power of the Seljuks however became diminished when the Seljuk Sultan Ahmed Sanjar was defeated by the Kara-Khitans at the Battle of Qatwan in 1141.

In the late twelfth century, a Turkic leader of Khorazm, which is the region south of the Aral Sea, united Khorazm, Transoxiana, and Iran under his rule. Under the rule of the Khorazm shah Kutbeddin Muhammad and his son, Muhammad II, Transoxiana continued to be prosperous and rich while maintaining the region's Perso-Islamic identity. However, a new incursion of nomads from the north soon changed this situation. This time the invader was Genghis Khan with his Mongol armies.[5]

Mongol period

The Mongol invasion of Central Asia is one of the turning points in the history of the region. The Mongols had such a lasting effect because they established the tradition that the legitimate ruler of any Central Asian state could only be a blood descendant of Genghis Khan.[8]

The Mongol conquest of Central Asia, which took place from 1219 to 1225, led to a wholesale change in the population of Mawarannahr. The conquest quickened the process of Turkification in some parts of the region because, although the armies of Genghis Khan were led by Mongols, they were made up mostly of Turkic tribes that had been incorporated into the Mongol armies as the tribes were encountered in the Mongols' southward sweep. As these armies settled in Mawarannahr, they intermixed with the local populations which did not flee. Another effect of the Mongol conquest was the large-scale damage the soldiers inflicted on cities such as Bukhoro and on regions such as Khorazm. As the leading province of a wealthy state, Khorazm was treated especially severely. The irrigation networks in the region suffered extensive damage that was not repaired for several generations.[8] Many Iranian-speaking populations were forced to flee southwards in order to avoid persecution.

Rule of Mongols and Timurids

Following the death of Genghis Khan in 1227, his empire was divided among his four sons and his family members. Despite the potential for serious fragmentation, Mongol law of the Mongol Empire maintained orderly succession for several more generations, and control of most of Mawarannahr stayed in the hands of direct descendants of Chaghatai, the second son of Genghis. Orderly succession, prosperity, and internal peace prevailed in the Chaghatai lands, and the Mongol Empire as a whole remained strong and united.[9] But, Khwarezm was part of Golden Horde.

In the early fourteenth century, however, as the empire began to break up into its constituent parts, the Chaghatai territory also was disrupted as the princes of various tribal groups competed for influence. One tribal chieftain, Timur (Tamerlane), emerged from these struggles in the 1380s as the dominant force in Mawarannahr. Although he was not a descendant of Genghis, Timur became the de facto ruler of Mawarannahr and proceeded to conquer all of western Central Asia, Iran, Asia Minor, and the southern steppe region north of the Aral Sea. He also invaded Russia before dying during an invasion of China in 1405.[9]

Timur initiated the last flowering of Mawarannahr by gathering in his capital, Samarqand, numerous artisans and scholars from the lands he had conquered. By supporting such people, Timur imbued his empire with a very rich Perso-Islamic culture. During Timur's reign and the reigns of his immediate descendants, a wide range of religious and palatial construction projects were undertaken in Samarqand and other population centers. Timur also patronized scientists and artists; his grandson Ulugh Beg was one of the world's first great astronomers. It was during the Timurid dynasty that Turkic, in the form of the Chaghatai dialect, became a literary language in its own right in Mawarannahr, although the Timurids were Persianate in nature. The greatest Chaghataid writer, Ali Shir Nava'i, was active in the city of Herat, now in northwestern Afghanistan, in the second half of the fifteenth century.[9]

The Timurid state quickly broke into two halves after the death of Timur. The chronic internal fighting of the Timurids attracted the attention of the Uzbek nomadic tribes living to the north of the Aral Sea. In 1501 the Uzbeks began a wholesale invasion of Mawarannahr.[9]

Uzbek period

By 1510 the Uzbeks had completed their conquest of Central Asia, including the territory of the present-day Uzbekistan. Of the states they established, the most powerful, the Khanate of Bukhoro, centered on the city of Bukhoro. The khanate controlled Mawarannahr, especially the region of Tashkent, the Fergana Valley in the east, and northern Afghanistan. A second Uzbek state, the Khanate of Khiva was established in the oasis of Khorazm at the mouth of the Amu Darya in 1512. The Khanate of Bukhoro was initially led by the energetic Shaybanid Dynasty. The Shaybanids competed against Iran, which was led by the Safavid Dynasty, for the rich far-eastern territory of present-day Iran. The struggle with Iran also had a religious aspect because the Uzbeks were Sunni Muslims, and Iran was Shia.[10]

Near the end of the sixteenth century, the Uzbek states of Bukhoro and Khorazm began to weaken because of their endless wars against each other and the Persians and because of strong competition for the throne among the khans in power and their heirs. At the beginning of the seventeenth century, the Shaybanid Dynasty was replaced by the Janid Dynasty.[10]

Another factor contributing to the weakness of the Uzbek khanates in this period was the general decline of trade moving through the region. This change had begun in the previous century when ocean trade routes were established from Europe to India and China, circumventing the Silk Route. As European-dominated ocean transport expanded and some trading centers were destroyed, cities such as Bukhoro, Merv, and Samarqand in the Khanate of Bukhoro and Khiva and Urganch (Urgench) in Khorazm began to steadily decline.[10]

The Uzbeks' struggle with Iran also led to the cultural isolation of Central Asia from the rest of the Islamic world. In addition to these problems, the struggle with the nomads from the northern steppe continued. In the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries, Kazakh nomads and Mongols continually raided the Uzbek khanates, causing widespread damage and disruption. In the beginning of the eighteenth century, the Khanate of Bukhoro lost the fertile Fergana region, and a new Uzbek khanate was formed in Quqon.[10]

Arrival of the Russians

The following period was one of weakness and disruption, with continuous invasions from Iran and from the north. In this period, a new group, the Russians, began to appear on the Central Asian scene. As Russian merchants began to expand into the grasslands of present-day Kazakhstan, they built strong trade relations with their counterparts in Tashkent and, to some extent, in Khiva. For the Russians, this trade was not rich enough to replace the former transcontinental trade, but it made the Russians aware of the potential of Central Asia. Russian attention also was drawn by the sale of increasingly large numbers of Russian slaves to the Central Asians by Kazakh and Turkmen tribes. Russians kidnapped by nomads in the border regions and Russian sailors shipwrecked on the shores of the Caspian Sea usually ended up in the slave markets of Bukhoro or Khiva. Beginning in the eighteenth century, this situation evoked increasing Russian hostility toward the Central Asian khanates.[11]

Meanwhile, in the late eighteenth and early nineteenth centuries new dynasties led the khanates to a period of recovery. Those dynasties were the Qongrats in Khiva, the Manghits in Bukhoro, and the Mins in Quqon. These new dynasties established centralized states with standing armies and new irrigation works. But their rise coincided with the ascendance of Russian power in the Kazakh steppes and the establishment of a British position in Afghanistan. By the early nineteenth century, the region was caught between these two powerful European competitors, each of which tried to add Central Asia to its empire in what came to be known as the Great Game. The Central Asians, who did not realize the dangerous position they were in, continued to waste their strength in wars among themselves and in pointless campaigns of conquest.[11]

Russian conquest

For the whole region see Russian conquest of Turkestan

In the nineteenth century, Russian interest in the area increased greatly, sparked by nominal concern over British designs on Central Asia; by anger over the situation of Russian citizens held as slaves; and by the desire to control the trade in the region and to establish a secure source of cotton for Russia. When the United States Civil War prevented cotton delivery from Russia's primary supplier, the southern United States, Central Asian cotton assumed much greater importance for Russia.[12]

As soon as the Russian conquest of the Caucasus was completed in the late 1850s, therefore, the Russian Ministry of War began to send military forces against the Central Asian khanates. Three major population centers of the khanates—Tashkent, Bukhoro, and Samarqand—were captured in 1865, 1867, and 1868, respectively. In 1868 the Khanate of Bukhoro signed a treaty with Russia making Bukhoro a Russian protectorate. In 1868 the Khanate of Kokand was confined to the Ferghana Valley and in 1876 it was annexed. The Khanate of Khiva became a Russian protectorate in 1873. Thus by 1876 the entire territory comprising present-day Uzbekistan either had fallen under direct Russian rule or had become a protectorate of Russia. The treaties establishing the protectorates over Bukhoro and Khiva gave Russia control of the foreign relations of these states and gave Russian merchants important concessions in foreign trade; the khanates retained control of their own internal affairs. Tashkent and Quqon fell directly under a Russian governor general.[12]

During the first few decades of Russian rule, the daily life of the Central Asians did not change greatly. The Russians substantially increased cotton production, but otherwise they interfered little with the indigenous people. Some Russian settlements were built next to the established cities of Tashkent and Samarqand, but the Russians did not mix with the indigenous populations. The era of Russian rule did produce important social and economic changes for some Uzbeks as a new middle class developed and some peasants were affected by the increased emphasis on cotton cultivation.[12]

In the last decade of the nineteenth century, conditions began to change as new Russian railroads brought greater numbers of Russians into the area. In the 1890s, several revolts, which were put down easily, led to increased Russian vigilance in the region. The Russians increasingly intruded in the internal affairs of the khanates. The only avenue for Uzbek resistance to Russian rule became the Pan-Turkish movement, also known as Jadidism, which had arisen in the 1860s among intellectuals who sought to preserve indigenous Islamic Central Asian culture from Russian encroachment. By 1900 Jadidism had developed into the region's first major movement of political resistance. Until the Bolshevik Revolution of 1917, the modern, secular ideas of Jadidism faced resistance from both the Russians and the Uzbek khans, who had differing reasons to fear the movement.[12]

Prior to the events of 1917, Russian rule had brought some industrial development in sectors directly connected with cotton. Although railroads and cotton-ginning machinery advanced, the Central Asian textile industry was slow to develop because the cotton crop was shipped to Russia for processing. As the tsarist government expanded the cultivation of cotton dramatically, it changed the balance between cotton and food production, creating some problems in food supply—although in the prerevolutionary period Central Asia remained largely self-sufficient in food. This situation was to change during the Soviet period when the Moscow government began a ruthless drive for national self-sufficiency in cotton. This policy converted almost the entire agricultural economy of Uzbekistan to cotton production, bringing a series of consequences whose harm still is felt today in Uzbekistan and other republics.[12]

Entering the twentieth century

By the turn of the twentieth century, the Russian Empire was in complete control of Central Asia. The territory of Uzbekistan was divided into three political groupings: the khanates of Bukhoro and Khiva and the Guberniya (Governorate General) of Turkestan, the last of which was under direct control of the Ministry of War of Russia. The final decade of the nineteenth century finds the three regions united under the independent and sovereign Republic of Uzbekistan. The intervening decades were a period of revolution, oppression, massive disruptions, and colonial rule.[13]

After 1900 the khanates continued to enjoy a certain degree of autonomy in their internal affairs. However, they ultimately were subservient to the Russian governor general in Tashkent, who ruled the region in the name of Tsar Nicholas II. The Russian Empire exercised direct control over large tracts of territory in Central Asia, allowing the khanates to rule a large portion of their ancient lands for themselves. In this period, large numbers of Russians, attracted by the climate and the available land, immigrated into Central Asia. After 1900, increased contact with Russian civilization began to affect the lives of Central Asians in the larger population centers where the Russians settled.[13]

The Jadidists and Basmachis

Russian influence was especially strong among certain young intellectuals who were the sons of the rich merchant classes. Educated in the local Muslim schools, in Russian universities, or in Istanbul, these men, who came to be known as the Jadidists, tried to learn from Russia and from modernizing movements in Istanbul and among the Tatars, and to use this knowledge to regain their country's independence. The Jadidists believed that their society, and even their religion, must be reformed and modernized for this goal to be achieved. In 1905 the unexpected victory of a new Asiatic power in the Russo-Japanese War and the eruption of revolution in Russia raised the hopes of reform factions that Russian rule could be overturned, and a modernization program initiated, in Central Asia. The democratic reforms that Russia promised in the wake of the revolution gradually faded, however, as the tsarist government restored authoritarian rule in the decade that followed 1905. Renewed tsarist repression and the reactionary politics of the rulers of Bukhoro and Khiva forced the reformers underground or into exile. Nevertheless, some of the future leaders of Soviet Uzbekistan, including Abdur Rauf Fitrat and others, gained valuable revolutionary experience and were able to expand their ideological influence in this period.[14]

In the summer of 1916, a number of settlements in eastern Uzbekistan were the sites of violent demonstrations against a new Russian decree canceling the Central Asians' immunity to conscription for duty in World War I. Reprisals of increasing violence ensued, and the struggle spread from Uzbekistan into Kyrgyz and Kazak territory. There, Russian confiscation of grazing land already had created animosity not present in the Uzbek population, which was concerned mainly with preserving its rights.[14]

The next opportunity for the Jadidists presented itself in 1917 with the outbreak of the February and October revolutions in Russia. In February the revolutionary events in Russia's capital, Petrograd (St. Petersburg), were quickly repeated in Tashkent, where the tsarist administration of the governor general was overthrown. In its place, a dual system was established, combining a provisional government with direct Soviet power and completely excluding the native Muslim population from power. Indigenous leaders, including some of the Jadidists, attempted to set up an autonomous government in the city of Quqon in the Fergana Valley, but this attempt was quickly crushed. Following the suppression of autonomy in Quqon, Jadidists and other loosely connected factions began what was called the Basmachi revolt against Soviet rule, which by 1922 had survived the civil war and was asserting greater power over most of Central Asia. For more than a decade, Basmachi guerrilla fighters (that name was a derogatory Slavic term that the fighters did not apply to themselves) fiercely resisted the establishment of Soviet rule in parts of Central Asia.[14]

However, the majority of Jadidists, including leaders such as Abdurrauf Fitrat and Fayzulla Khodzhayev, cast their lot with the communists. In 1920 Khojayev, who became first secretary of the Communist Party of Uzbekistan, assisted communist forces in the capture of Bukhoro and Khiva. After the Amir of Bukhoro had joined the Basmachi movement, Khojayev became president of the newly established Bukharan People's Soviet Republic. A People's Republic of Khorezm also was set up in what had been Khiva.[14]

The Basmachi revolt eventually was crushed as the civil war in Russia ended and the communists drew away large portions of the Central Asian population with promises of local political autonomy and the potential economic autonomy of Soviet leader Lenin's New Economic Policy. Under these circumstances, large numbers of Central Asians joined the communist party, many gaining high positions in the government of the Uzbek Soviet Socialist Republic (Uzbek SSR), the administrative unit established in 1924 to include present-day Uzbekistan and Tajikistan. The indigenous leaders cooperated closely with the communist government in enforcing policies designed to alter the traditional society of the region: the emancipation of women, the redistribution of land, and mass literacy campaigns.[14]

The Stalinist period

In 1929 the Tajik and Uzbek Soviet socialist republics were separated. As Uzbek communist party chief, Khojayev enforced the policies of the Soviet government during the collectivization of agriculture in the late 1920s and early 1930s and, at the same time, tried to increase the participation of Uzbeks in the government and the party. Soviet leader Joseph V. Stalin suspected the motives of all reformist national leaders in the non-Russian republics of the Soviet Union. By the late 1930s, Khojayev and the entire group that came into high positions in the Uzbek Republic had been arrested and executed during the Stalinist purges.[15]

Following the purge of the nationalists, the government and party ranks in Uzbekistan were filled with people loyal to the Moscow government. Economic policy emphasized the supply of cotton to the rest of the Soviet Union, to the exclusion of diversified agriculture. During World War II, many industrial plants from European Russia were evacuated to Uzbekistan and other parts of Central Asia. With the factories came a new wave of Russian and other European workers. Because native Uzbeks were mostly occupied in the country's agricultural regions, the urban concentration of immigrants increasingly Russified Tashkent and other large cities. During the war years, in addition to the Russians who moved to Uzbekistan, other nationalities such as Crimean Tatars, Chechens, and Koreans were exiled to the republic because Moscow saw them as subversive elements in European Russia.[15]

Khrushchev and Brezhnev rule

Following the death of Joseph Stalin in 1953, the relative relaxation of totalitarian control initiated by First Secretary Nikita Khrushchev (in office 1953-64) brought the rehabilitation of some of the Uzbek nationalists who had been purged. More Uzbeks began to join the Communist Party of Uzbekistan and to assume positions in the government. However, those Uzbeks who participated in the regime did so on Russian terms.[16] Russian was the language of state, and Russification was the prerequisite for obtaining a position in the government or the party. Those who did not or could not abandon their Uzbek lifestyles and identities were excluded from leading roles in official Uzbek society. Because of these conditions, Uzbekistan gained a reputation as one of the most politically conservative republics in the Soviet Union.[16]

As Uzbeks were beginning to gain leading positions in society, they also were establishing or reviving unofficial networks based on regional and clan loyalties. These networks provided their members support and often profitable connections between them and the state and the party. An extreme example of this phenomenon occurred under the leadership of Sharaf Rashidov, who was first secretary of the Communist Party of Uzbekistan from 1959 to 1982. During his tenure, Rashidov brought numerous relatives and associates from his native region into government and party leadership positions. The individuals who thus became "connected" treated their positions as personal fiefdoms to enrich themselves.[16]

In this way, Rashidov was able to initiate efforts to make Uzbekistan less subservient to Moscow. As became apparent after his death, Rashidov's strategy had been to remain a loyal ally of Leonid Brezhnev, leader of the Soviet Union from 1964 to 1982, by bribing high officials of the central government. With this advantage, the Uzbek government was allowed to merely feign compliance with Moscow's demands for increasingly higher cotton quotas.[16]

The 1980s

During the decade following the death of Rashidov, Moscow attempted to regain the central control over Uzbekistan that had weakened in the previous decade. In 1986 it was announced that almost the entire party and government leadership of the republic had conspired in falsifying cotton production figures. Eventually, Rashidov himself was also implicated (posthumously) together with Yuri Churbanov, Brezhnev's son-in-law. A massive purge of the Uzbek leadership was carried out, and corruption trials were conducted by prosecutors brought in from Moscow. In the Soviet Union, Uzbekistan became synonymous with corruption. The Uzbeks themselves felt that the central government had singled them out unfairly; in the 1980s, this resentment led to a strengthening of Uzbek nationalism. Moscow's policies in Uzbekistan, such as the strong emphasis on cotton and attempts to uproot Islamic tradition, then came under increasing criticism in Tashkent.[17]

In 1989 ethnic animosities came to a head in the Fergana Valley, where local Meskhetian Turks were assaulted by Uzbeks, and in the Kyrgyz city of Osh, where Uzbek and Kyrgyz youth clashed. Moscow's response to this violence was a reduction of the purges and the appointment of Islam Karimov as first secretary of the Communist Party of Uzbekistan. The appointment of Karimov, who was not a member of the local party elite, signified that Moscow wanted to lessen tensions by appointing an outsider who had not been involved in the purges.[17]

Resentment among Uzbeks continued to smolder, however, in the liberalized atmosphere of Soviet leader Mikhail Gorbachev's policies of perestroika and glasnost. With the emergence of new opportunities to express dissent, Uzbeks expressed their grievances over the cotton scandal, the purges, and other long-unspoken resentments. These included the environmental situation in the republic, recently exposed as a catastrophe as a result of the long emphasis on heavy industry and a relentless pursuit of cotton. Other grievances included discrimination and persecution experienced by Uzbek recruits in the Soviet army and the lack of investment in industrial development in the republic to provide jobs for the ever-increasing population.[17]

By the late 1980s, some dissenting intellectuals had formed political organizations to express their grievances. The most important of these, Birlik (Unity), initially advocated the diversification of agriculture, a program to salvage the desiccated Aral Sea, and the declaration of the Uzbek language as the state language of the republic. Those issues were chosen partly because they were real concerns and partly because they were a safe way of expressing broader disaffection with the Uzbek government. In their public debate with Birlik, the government and party never lost the upper hand. As became especially clear after the accession of Karimov as party chief, most Uzbeks, especially those outside the cities, still supported the communist party and the government. Birlik's intellectual leaders never were able to make their appeal to a broad segment of the population.[17]

1991 to present

The attempted coup against the Gorbachev government by disaffected hard-liners in Moscow, which occurred in August 1991, was a catalyst for independence movements throughout the Soviet Union. Despite Uzbekistan's initial hesitancy to oppose the coup, the Supreme Soviet of Uzbekistan declared the republic independent on August 31, 1991. In December 1991, an independence referendum was passed with 98.2 percent of the popular vote. The same month, a parliament was elected and Karimov was chosen the new nation's first president.[18]

Although Uzbekistan had not sought independence, when events brought them to that point, Karimov and his government moved quickly to adapt themselves to the new realities. They realized that under the Commonwealth of Independent States, the loose federation proposed to replace the Soviet Union, no central government would provide the subsidies to which Uzbek governments had become accustomed for the previous 70 years. Old economic ties would have to be reexamined and new markets and economic mechanisms established. Although Uzbekistan as defined by the Soviets had never had independent foreign relations, diplomatic relations would have to be established with foreign countries quickly. Investment and foreign credits would have to be attracted, a formidable challenge in light of Western restrictions on financial aid to nations restricting expression of political dissent. For example, the suppression of internal dissent in 1992 and 1993 had an unexpectedly chilling effect on foreign investment. Uzbekistan's image in the West alternated in the ensuing years between an attractive, stable experimental zone for investment and a post-Soviet dictatorship whose human rights record made financial aid inadvisable. Such alternation exerted strong influence on the political and economic fortunes of the new republic in its first five years.[18]

The activities of missionaries from some Islamic countries, coupled with the absence of real opportunities to participate in public affairs, contributed to the popularization of a radical interpretation of Islam. In the February 1999 Tashkent bombings, car bombs hit Tashkent and President Karimov narrowly escaped an assassination attempt. The government blamed the Islamic Movement of Uzbekistan (IMU) for the attacks. Thousands of people suspected of complicity were arrested and imprisoned. In August 2000, militant groups tried to penetrate Uzbek territory from Kyrgyzstan; acts of armed violence were noted in the southern part of the country as well.

In March 2004, another wave of attacks shook the country. These were reportedly committed by an international terrorist network. An explosion in the central part of Bukhara killed ten people in a house allegedly used by terrorists on March 28, 2004. Later that day, policemen were attacked at a factory, and early the following morning a police traffic check point was attacked. The violence escalated on March 29, when two women separately set off bombs near the main bazaar in Tashkent, killing two people and injuring around 20. These were the first suicide bombers in Uzbekistan. On the same day, three police officers were shot dead. In Bukhara, another explosion at a suspected terrorist bomb factory caused ten fatalities. The following day police raided an alleged militant hideout south of the capital city.

President Karimov claimed the attacks were probably the work of a banned radical group Hizb ut-Tahrir ("The Party of Liberation"), although the group denied responsibility. Other groups that might have been responsible include militant groups operating from camps in Tajikistan and Afghanistan and opposed to the government's support of the United States since September 11, 2001.

In 2004, British ambassador Craig Murray was removed from his post after speaking out against the regime's human rights abuses and British collusion therein.[19]

On July 30, 2004, terrorists bombed the embassies of Israel and the United States in Tashkent, killing three people and wounding several. The Jihad Group in Uzbekistan posted a claim of responsibility for those attacks on a website linked to Al-Qaeda. Terrorism experts say the reason for the attacks is Uzbekistan's support of the United States and its War on terror.

In May 2005, several hundred demonstrators were killed when Uzbek troops fired into a crowd protesting against the imprisonment of 23 local businessmen. (For further details, see Andijan massacre.)

In July 2005, the Uzbek government gave the US 180 days' notice to leave the airbase it had leased in Uzbekistan. A Russian airbase and a German airbase remain.

In December 2007 Islam A. Karimov was reelected to power in a fraudulent election. Western election observers noted that the election failed to meet many OSCE benchmarks for democratic elections, the elections were held in a strictly controlled environment, and there had been no real opposition since all the candidates publicly endorsed the incumbent. Human rights activists reported various cases of multiple voting throughout the country as well as official pressure on voters at polling stations to cast ballots for Karimov.[20] The BBC reported that many people were afraid to vote for anyone other than the president.[21] According to the constitution Karimov was ineligible to stand as a candidate, having already served two consecutive presidential terms and thus his candidature was illegal.[22][23]

The lead up to the elections was characterized by the secret police arresting dozens of opposition activists and putting them in jail including Yusuf Djumayaev, an opposition poet. Several news organizations, including The New York Times, the BBC and the Associated Press, were denied credentials to cover the election.[22] Around 300 dissidents were in jail in 2007, including Jamshid Karimov, the president's 41-year-old nephew.[23]

See also

References

Footnotes

- 1 2 3 4 5 "Country Profile: Uzbekistan". Library of Congress Federal Research Division (February 2007). This article incorporates text from this source, which is in the public domain.

- ↑ "Teshik-Tash | The Smithsonian Institution's Human Origins Program". Humanorigins.si.edu. 2010-03-24. Retrieved 2013-09-15.

- 1 2 3 Lubin, Nancy. "Early history". In Curtis.

- 1 2 3 4 Lubin, Nancy. "Early Islamic period". In Curtis.

- 1 2 3 4 Lubin, Nancy. "Turkification of Mawarannahr". In Curtis.

- ↑ Davidovich, E. A. (1998), "Chapter 6 The Karakhanids", in Asimov, M.S.; Bosworth, C.E., History of Civilisations of Central Asia, 4 part I, UNESCO Publishing, pp. 119–144, ISBN 92-3-103467-7

- ↑ Golden, Peter. B. (1990), "The Karakhanids and Early Islam", in Sinor, Denis, The Cambridge History of Early Inner Asia, Cambridge University Press, ISBN 0-521-24304-1

- 1 2 Lubin, Nancy. "Mongol period". In Curtis.

- 1 2 3 4 Lubin, Nancy. "Rule of Timur". In Curtis.

- 1 2 3 4 Lubin, Nancy. "Uzbek period". In Curtis.

- 1 2 Lubin, Nancy. "Arrival of the Russians". In Curtis.

- 1 2 3 4 5 Lubin, Nancy. "Russian conquest". In Curtis.

- 1 2 Lubin, Nancy. "Entering the twentieth century". In Curtis.

- 1 2 3 4 5 Lubin, Nancy. "The Jadidists and Basmachis". In Curtis.

- 1 2 Lubin, Nancy. "The Stalinist period". In Curtis.

- 1 2 3 4 Lubin, Nancy. "Russification and resistance". In Curtis.

- 1 2 3 4 Lubin, Nancy. "The 1980s". In Curtis.

- 1 2 Lubin, Nancy. "Independence". A Country Study: Uzbekistan (Glenn E. Curtis, editor). Library of Congress Federal Research Division (March 1996). This article incorporates text from this source, which is in the public domain.

- ↑ MacAskill, Ewen (October 22, 2004). "Ex-envoy to face discipline charges,says FO". The Guardian. London. Retrieved May 4, 2010.

- ↑ "Uzbek Leader Wins New Term". CBS News. 2007-12-24.

- ↑ "Uzbek president wins third term". BBC News. 2007-12-24. Retrieved January 5, 2010.

- 1 2 Stern, David L. (2007-12-25). "Uzbekistan Re-elects Its President". The New York Times. Retrieved May 4, 2010.

- 1 2 Harding, Luke (2007-12-24). "Uzbek president returned in election 'farce'". London: The Guardian. Retrieved May 4, 2010.

Works cited

- Curtis, Glenn E., editor. A Country Study: Uzbekistan. Library of Congress Federal Research Division (March 1996). This article incorporates text from this source, which is in the public domain.