History of steam road vehicles

The history of steam road vehicles describes the development of vehicles powered by a steam engine for use on land and independent of rails; whether for conventional road use, such as the steam car and steam waggon, or for agricultural or heavy haulage work, such as the traction engine.

The first experimental vehicles were built in the 17th and 18th century, but it was not until after Richard Trevithick had developed the use of high-pressure steam, around 1800, that mobile steam engines became a practical proposition. The first half of the 19th century saw great progress in steam vehicle design, and by the 1850s it was viable to produce them on a commercial basis. This progress was dampened by legislation which limited or prohibited the use of steam powered vehicles on roads. Nevertheless, the 1880s to the 1920s saw continuing improvements in vehicle technology and manufacturing techniques, and steam road vehicles were developed for many applications. In the 20th century, the rapid development of internal combustion engine technology led to the demise of the steam engine as a source of propulsion of vehicles on a commercial basis, with relatively few remaining in use beyond the Second World War. Many of these vehicles were acquired by enthusiasts for preservation, and numerous examples are still in existence. In the 1960s the air pollution problems in California gave rise to a brief period of interest in developing and studying steam powered vehicles as a possible means of reducing the pollution. Apart from interest by steam enthusiasts, the occasional replica vehicle, and experimental technology no steam vehicles are in production at present.

Early pioneers

Early research on the steam engine before 1700 was closely linked to the quest for self-propelled vehicles and ships; the first practical applications from 1712 were stationary plant working at very low pressure which entailed engines of very large dimensions. The size reduction necessary for road transport meant an increase in steam pressure with all the attendant dangers, due to the inadequate boiler technology of the period. A strong opponent of high pressure steam was James Watt who, along with Matthew Boulton did all he could to dissuade William Murdoch from developing and patenting his steam carriage, built in model form in 1784.

Ferdinand Verbiest is suggested to have built what may have been the first steam powered car in about 1672,[1][2] but very little concrete information on this is known to exist.

During the latter part of the 18th century, there were numerous attempts to produce self-propelled steerable vehicles. Many remained in the form of models. Progress was dogged by many problems inherent to road vehicles in general, such as suitable power-plant giving steady rotative motion, suspension, braking, steering, adequate road surfaces, tyres, and vibration-resistant bodywork, among other issues. The extreme complexity of these issues can be said to have hampered progress over more than a hundred years, as much as hostile legislation.

Cugnot's "Fardier à vapeur"

Nicolas-Joseph Cugnot's "machine à feu pour le transport de wagons et surtout de l'artillerie" ("fire engine for transporting wagons and especially artillery") was built from 1769 in two versions for use by the French Army. This was the first steam wagon that was not a toy, and that was known to exist. Cugnot's fardier, a term usually applied to a massive two-wheeled cart for exceptionally heavy loads, was intended to be capable of transporting 4 tonnes (3.9 tons), and of travelling at up to 4 km/h (2.5 mph). The vehicle was of tricycle layout, with two rear wheels and a steerable front wheel controlled by a tiller. There is considerable evidence, from the period, that this vehicle actually ran, making it probably the first to do so; however it remained a short-lived experiment due to inherent instability and the vehicle's failure to meet the Army's specified performance level.

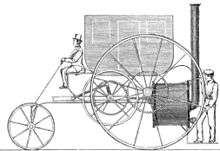

Trevithick's steam carriage

In 1801, Richard Trevithick constructed an experimental steam-driven vehicle (Puffing Devil) which was equipped with a firebox enclosed within the boiler, with one vertical cylinder, the motion of the single piston being transmitted directly to the driving wheels by means of connecting rods. It was reported as weighing 1520 kg fully loaded, with a speed of 14.5 km/h (9 mph) on the flat. During its first trip it was left unattended and "self-destructed". Trevithick soon built the London Steam Carriage that ran successfully in London in 1803, but the venture failed to attract interest and soon folded up.

In the context of Trevithick's vehicle, an English writer by the name of "Mickleham" in 1822 coined the term Steam Engine:

- "It exhibits in construction the most beautiful simplicity of parts, the most sagacious selection of appropriate forms, the most convenient and effective arrangement and connexion; uniting strength with elegance; the necessary solidity with the greatest portability; possessing unlimited power with a wonderful pliancy to accommodate it to the varying resistance: it may indeed be called The Steam Engine."[3]

Steam-powered amphibious craft

In 1805 Oliver Evans built the "Oruktor Amphibolos" (literally 'amphibious digger'), a steam-powered, flat-bottomed dredger that he modified to be self-propelled on both land and water. It is widely believed to be the first amphibious vehicle, and the first steam-powered road vehicle to run in the United States. However, no designs for the machine survive, and the only accounts of its achievements come from Evans himself. Later analysis of Evans's descriptions suggests that the 5hp engine was unlikely to have been powerful enough to move the vehicle either on land or water, and that the chosen route for its demonstration would have had the benefit of gravity, river currents and tides to assist with the vehicles' progress. The dredger was not a success, and after a few years lying idle, was dismantled for parts.[4]

Early steam carriage services

More commercially successful for a time than Trevithick's carriage were the steam carriage services operated in England in the 1830s, principally by Walter Hancock and associates of Sir Goldsworthy Gurney, among others and in Scotland by John Scott Russell. However, the heavy road tolls imposed by the Turnpike Acts discouraged steam road vehicles and for a short time allowed the continued monopoly of horse traction until railway trunk routes became established in the 1840s and '50s.

Victorian Age of Steam

Although engineers developed ingenious steam-powered road vehicles, they did not enjoy the same level of acceptance and expansion as steam power at sea and on the railways in the middle and late 19th century of the "Age of Steam".

Harsh legislation virtually eliminated mechanically propelled vehicles from the roads of Great Britain for 30 years, the Locomotive Act of 1861 imposing restrictive speed limits on "road locomotives" of 5 mph (8 km/h) in towns and cities, and 10 mph (16 km/h) in the country. In 1865 the Locomotives Act of that year (the famous Red Flag Act) further reduced the speed limits to 4 mph (6.4 km/h) in the country and just 2 mph (3.2 km/h) in towns and cities, additionally requiring a man bearing a red flag (red lantern during the hours of darkness) to precede every vehicle. At the same time, the act gave local authorities the power to specify the hours during which any such vehicle might use the roads. The sole exceptions were street trams which from 1879 onwards were authorised under licence from the Board of Trade.

In France the situation was radically different from the extent of the 1861 ministerial ruling formally authorising the circulation of steam vehicles on ordinary roads. Whilst this led to considerable technological advances throughout the 1870s and '80s, steam vehicles nevertheless remained a rarity.

To an extent competition from the successful railway network reduced the need for steam vehicles. From the 1860s onwards, attention was turned more to the development of various forms of traction engine which could either be used for stationary work such as sawing wood and threshing, or for transporting outsize loads too voluminous to go by rail. Steam trucks were also developed but their use was generally confined to the local distribution of heavy materials such as coal and building materials from railway stations and ports.

Thomas Rickett of Buckingham

In 1858 Thomas Rickett of Buckingham built the first of several steam carriages. Instead of looking like a carriage, it resembled a small locomotive. It consisted of a steam-engine mounted on three wheels: two large driven rear wheels and one smaller front wheel by which the vehicle was steered. The whole was driven by a chain drive and a maximum speed of twelve miles per hour was reached. The weight of the machine was 1.5 tonnes and somewhat lighter than Rickett's steam carriage.

Two years later, in 1860, Rickett built a similar but heavier vehicle. This model incorporated spur-gear drive instead of chain. In his final design, resembling a railway locomotive, the cylinders were coupled directly outside the cranks of the driving-axle.

Innocenzo Manzetti's steam car.

In 1864, Italian inventor Innocenzo Manzetti built a road-steamer.[5] It had the boiler at the front and a single-cylinder engine.[5]

Henry Taylor's steam buggy

In 1867, Canadian jeweller Henry Seth Taylor demonstrated his four-wheeled steam buggy at the Stanstead Fair in Stanstead, Quebec, and again the following year.[6] The basis of the buggy, which he began building in 1865, was a high-wheeled carriage with bracing to support a two-cylinder steam engine mounted on the floor.[7]

Michaux-Perreaux steam velocipede

Around 1867–1869 in France, a Louis-Guillaume Perreaux commercial steam engine was attached to a Pierre Michaux metal framed velocipede, creating the Michaux-Perreaux steam velocipede.[8] Along with the Roper steam velocipede, it might have been the first motorcycle.[8][9][10][11] The only Michaux-Perreaux steam velocipede made is in the Musée de l'Île-de-France, Sceaux, and was included in The Art of the Motorcycle exhibition in New York in 1998.[12]

Sylvester H. Roper

Sylvester H. Roper drove around Boston, Massachusetts on a steam carriage he invented in 1863.[13][14][15][16][17] One of his 1863 carriages went to the Henry Ford Museum, where, in 1972, it was the oldest car in the collection.[15][16][18] Around 1867–1869 he built a steam velocipede, which may have been the first motorcycle.[8][9][11] Roper died in 1896 of heart failure while testing a later version of his steam motorcycle.[19]

H.P. Holt

H.P. Holt constructed a small road-steamer in 1866. Able to reach a speed of twenty miles per hour on level roads, it had a vertical boiler at the rear and two separate twin cylinder engines, each of which drove one rear wheel by means of a chain and sprocket wheels.

Catley and Ayres of York

In 1869, a small three-wheeled vehicle propelled by a horizontal twin cylinder engine which drove the rear axle by spur-gearing; only one rear wheel was driven, the other turning freely on the axle. A vertical fire-tube boiler was mounted at the rear with a polished copper casing over the fire box and chimney; the boiler was enclosed in a mahogany casing. The front wheel was used for steering and the weight was only 19 cwt.

J.H. Knight of Farnham

1868 - 1870, John Henry Knight of Farnham built a four-wheeled steam carriage which originally only had a single-cylinder engine.

R.W. Thomson of Edinburgh

1869, The road-steamer built by Robert William Thomson of Edinburgh became famous because its wheels were shod with heavy solid rubber tyres.

Charles Randolph of Glasgow

1872, a steam-coach by Charles Randolph of Glasgow was 15 feet (5 m) in length, weighed four and a half tons, but had a maximum speed of only 6 miles per hour. Two vertical twin-cylinder engines were independent of one another and each drove one of the rear wheels by spur-gearing. The entire vehicle was enclosed and fitted with windows all around, carried six people, and even had two driving mirrors for observing traffic approaching from behind, the earliest recorded instance of such a device.

R. Neville Grenville of Glastonbury

In 1875, R. Neville Grenville of Glastonbury constructed a 3-wheeled steam vehicle which travelled a maximum of 15 miles per hour. This vehicle is still in existence, preserved in the Bristol City Museum.

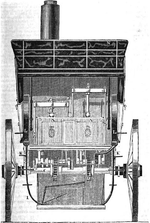

Amédée Bollée

From 1873 to 1883 Amédée Bollée of Le Mans built a series of steam-powered passenger vehicles able to carry 6 to 12 people at speeds up to 60 km/h (38 mph), with such names as Rapide and L'Obeissante. In his vehicles the boiler was mounted behind the passenger compartment with the engine at the front of the vehicle, driving the differential through a shaft with chain drive to the rear wheels. The driver sat behind the engine and steered by means of a wheel mounted on a vertical shaft. The lay-out more closely resembled much later motor cars than other steam vehicles. L'Obeissante, moreover, in 1873 had independent suspension on all four corners.[20]

Cederholm brothers

In 1892, painter Joens Cederholm and his brother, André, a blacksmith, designed their first car, a two-seater, introducing a condensor in 1894. It was not a success.[21]

De Dion & Bouton steam vehicles

- See steam tricycle

The development by Serpollet of the flash steam boiler[22] brought about the appearance of various diminutive steam tricycles and quadricycles during the late 80s and early 90s, notably by de Dion and Bouton; these successfully competed in long distance races but soon met with stiff competition for public favour from the internal combustion engine cars being developed, notably by Peugeot, that quickly cornered most of the popular market. In the face of the flood of IC cars, proponents of the steam car had to fight a long rear-guard battle that was to last into modern times.

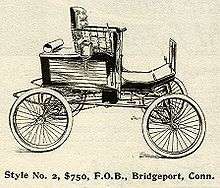

Locomobile Company of America

This American firm bought the patents from the Stanley Brothers and began building their steam buggies from 1898 to 1905. Locomobile Company of America went into building gas cars and lasted until the Depression.

Stanley Motor Carriage Company

In 1902, Francis E. Stanley (1849–1918) and Freelan O. Stanley formed the Stanley Motor Carriage Company. They made famous models such as the 1906 Stanley Rocket, 1908 Stanley K Raceabout and 1923 Stanley Steam Car.[23]

Military application of steam road vehicles

During the Crimean war a traction engine was used to pull multiple open trucks.[24]

In the 1870s many armies experimented with steam tractors pulling road trains of supply wagons.[25]

By 1898 steam traction engine trains with up to four wagons were employed in military manoeuvres in England.[26]

In 1900, John Fowler & Co. provided armoured road trains for use by the British forces in the Second Boer War.[24][27][28]

Early to mid 20th century

In 1906 the Land Speed Record was broken by a Stanley steam car, piloted by Fred Marriott, which achieved 127 mph (203 km/h) at Ormond Beach, Florida. This annual week-long "Speed Week" was the forerunner of today's Daytona 500. This record was not exceeded by any land vehicle until 1910, and stood as the steam-powered world speed record till 25 August 2009.

Doble Steam Car

Attempts were made to bring more advanced steam cars on the market, the most remarkable being the Doble Steam Car[29] which shortened start-up time very noticeably by incorporating a highly efficient monotube steam generator to heat a much smaller quantity of water along with effective automation of burner and water feed control. By 1923, Doble's steam cars could be started from cold with the turn of a key and driven off in 40 seconds or less.

Paxton Phoenix

Abner Doble developed the Doble Ultimax engine for the Paxton Phoenix steam car, built by the Paxton Engineering Division of McCulloch Motors Corporation, Los Angeles. Its sustained maximum power was 120 bhp (89 kW). The project was eventually dropped in 1954.[30]

Decline of steam car development

Steam cars became less popular after the adoption of the electric starter, which eliminated the need for risky hand cranking to start gasoline-powered cars. The introduction of assembly-line mass production by Henry Ford, which hugely reduced the cost of owning a conventional automobile, was also a strong factor in the steam car's demise as the Model T was both cheap and reliable.

Late 20th century

Renewed interest

In 1968, renewed interest was shown, sometimes prompted by newly available techniques. An older idea that was resurrected is to use a water-tube generator with fire around it, as opposed to using firetubes heating a boiler of water.[31] A prototype car was built by Charles J. & Calvin E. Williams of Ambler, Pennsylvania. Other high-performance steam cars were built by Richard J.Smith of Midway City, California, and A.M. and E. Pritchard of Caulfeld, Australia. Companies/organisations as Controlled Steam Dynamics of Mesa, Arizona, General Motors, Thermo-Electron Corp. of Waltham, Massachusetts, and Kinetics Inc, of Sarasota, Florida all built high-performance steam engines in the same period. Bill Lear also started work on a closed circuit steam turbine to power cars and buses, and built a transit bus and converted a Chevrolet Monte Carlo sedan to use this turbine system. It used a proprietary working fluid dubbed Learium, possibly a chlorofluorocarbon similar to DuPont Freon.[32]

In 1970, a variant of the steam car was made by Wallace L.Minto, which works on Ucon U-113 fluorocarbon as the working fluid (instead of steam) and kerosene, gasoline, or the like as a fuel. The car was called the Minto car.[33][34]

Land speed record

On 25 August 2009, a team of British engineers from Hampshire ran their steam powered car "Inspiration" at Edwards Air Force Base in the Mojave Desert, and averaged 139.84 mph (225.05 km/h) over two runs, driven by Charles Burnett III. The car was 7.62 m (300 in) long and weighed 3,000 kg (6,614 lb), built from carbon fibre and aluminium and contained 12 boilers with over 2 miles (3.2 km) of steam tubing.[35]

Modern steam vehicles

Today most of the problems facing steam cars have been satisfactorily solved, but not the core problem of the low fuel efficiency achieved by practical road going engines.

The main upside would be the ability to burn fuels currently wasted, such as garbage, wood scrap, and fuels of low value such as crude oil.

Currently the re-introduction of any modern steam car project would run up against the problem of a general loss of steam engine culture which would make it difficult to set up an infrastructure of spares and qualified mechanics. It would also be necessary to meet more stringent safety standards and legislation than existed in the heyday of steam-powered road vehicles. The biggest arguments in favour of such a movement would be: greatly reduced pollution by particulates and noxious gases without recourse to filters, silence in operation, and direct drive without a gearbox. However the competition which development of a modern steam-powered vehicle has to consider is not so much from gasoline-powered cars as from electric, hydrogen-powered and hybrid vehicles.

Proposed nuclear cars, would actually be steam powered with the steam generated from the heat of a nuclear reaction. Nuclear power is probably the best known commercial use of steam in the 21st century, because every nuclear power plant uses steam in a similar manner.

Gallery

-

.jpg)

William Murdoch's model steam carriage

-

A replica of Richard Trevithick's 1801 road locomotive Puffing Devil

-

The Oruktor Amphibolos, Oliver Evans (1805)

See also

- History of the automobile – mainly covers later, internal combustion vehicles

- List of steam car makers

- Steam engine

- Steam bus

- Steam car

- The Steam House (Jules Verne novel)

- Timeline of motor vehicle brands

- List of motorized trikes

References

- ↑ "1679-1681 – R P Verbiest's Steam Chariot". History of the Automobile: origin to 1900. Hergé. Retrieved 2009-05-08.

- ↑ Setright, L. J. K. (2004). Drive On!: A Social History of the Motor Car. Granta Books. ISBN 1-86207-698-7.

- ↑ Luke Hebert: The Engineer's and Mechanic's Encyclopædia, Vol. 2, Pg. 612, 1849

- ↑ Lubar, Steve. "Was This America's First Steamboat, Locomotive, and Car?". Invention and Technology Magazine, Spring 2006, Volume 21, Issue 4. (at American Heritage.com). Retrieved 2008-04-09.

- 1 2 (Italian) Innocenzo Manzetti - Le invenzioni

- ↑ The Montreal Gazette - 18 Jan 1986 https://news.google.com/newspapers?nid=1946&dat=19860118&id=G4Y0AAAAIBAJ&sjid=5KUFAAAAIBAJ&pg=3436,3937822

- ↑ "Canada's First Automobile: Full Steam Ahead" from the book "Whatever Happened To...?" by Mark Kearny & Randy Ray, Dundern Press, 2006

- 1 2 3 Falco, Charles M.; Guggenheim Museum Staff (1998), "Issues in the Evolution of the Motorcycle", in Krens, Thomas; Drutt, Matthew, The Art of the Motorcycle, Harry N. Abrams, pp. 24–31, 98–101, ISBN 0-89207-207-5

Michaux-Perreaux year 1868. Roper year 1869. - 1 2 Setright, L. J. K. (1979). The Guinness Book of Motorcycling Facts and Feats. Guinness Superlatives. pp. 8–18. ISBN 0-85112-200-0.

- ↑ Kresnak, Bill (2008), Motorcycling for Dummies, Hoboken, New Jersey: For Dummies, Wiley Publishing, p. 29, ISBN 0-470-24587-5

- 1 2 Kerr, Glynn (August 2008), "Design; The Conspiracy Theory", Motorcycle Consumer News, Irvine, California: Aviation News Corp, vol. 39 no. 8, p. 36–37, ISSN 1073-9408

- ↑ Falco, Charles M. (July 2003), "The Art and Materials Science of 190-mph Superbikes" (Adobe PDF), MRS Bulletin, 28 (7), retrieved 2011-01-29

Michaux-Perreaux year 1867–1871. - ↑ Lowell Daily Citizen and News, Lowell, Massachusetts (2050), 6 January 1863,

S. H. Roper, of Roxbury, has invented a steam wagon for common roads, which stops, turns corners, backs, 'keeps to the right as the law directs,' and does many other intelligent things under the hands of a skilful driver.

Missing or empty|title=(help) - ↑ "Miscellaneous Items; Mr Sylvester H Roper of Roxbury, Mass has invented a steam carriage…", New Haven Daily Palladium, New Haven, Connecticut (52), 3 March 1863

- 1 2 Pearson, Drew (16 May 1965), "Ford Museum Houses U.S. History", Daytona Beach Sunday News-Journal, p. 8, retrieved 2011-02-06

- 1 2 McCann, Hugh (2 April 1972), "Museum Traces History of Wheels", The New York Times, pp. IA27

- ↑ See also:

- "An improved steam carriage," Scientific American, new series, vol. 8, no. 11, page 165 (14 March 1863).

- "New steam carriage," Scientific American, new series, vol. 9, no 22, page 341 (28 November 1863).

- ↑ Johnson, Paul F., Sylvester Roper's steam carriage, Smithsonian Institution, retrieved 2011-02-06

- ↑ "Died in the Saddle", Boston Daily Globe, p. 1, 2 June 1896

- ↑ Csere, Csaba (January 1988), "10 Best Engineering Breakthroughs", Car and Driver, 33 (7), p. 61.

- ↑ G.N. Georgano Cars: Early and Vintage, 1886-1930. (London: Grange-Universal, 1985).

- ↑ Combe Jean-Marc & Escudier Bernard (1986, L'Aventure scientifique et technique de la vapeur; editions du CNRS, Paris, France; ISBN 2-222-03794-8

- ↑ Models of Stanley Motor Carriage Company

- 1 2 Beavan, Arthur H. (1903). Tube, Train, Tram, and Car or Up-to-date Locomotion. London: G. Routledge & sons. p. 217.

- ↑ Steam Tractors the Power Behind First Motorized Armored Vehicles

- ↑ Layriz, Otfrie; Marston, Robert Bright (1900). Mechanical traction in war for road transport, with notes on automobiles generally. London: S. Low, Marston and Company. p. 20.

- ↑ The Illustrated war news. 29 November 1916.

- ↑ Steam Tractors the Power Behind First Motorized Armored Vehicles

- ↑ Walton J.N. (1965-74) Doble Steam Cars, Buses, Lorries, and Railcars . "Light Steam Power" Isle of Man, UK.

- ↑ "The True Story of the Paxton Phoenix." Road and Track, April 1957. pp. 13 - 18

- ↑ Is there a steam car in your future

- ↑ Ethridge. John. "PM takes a ride in tomorrow's bus, today." Popular Mechanics, August 1972. Retrieved: 31 August 2011.

- ↑ Minto car

- ↑ Minto car mentioned in Steam Car books

- ↑ "UK team breaks steam car record". BBC News. 25 August 2009. Retrieved 4 May 2010.

External links

- History of the Automobile – includes drawings of many early steam vehicles (Newton, Cugnot, Trevithick, Gurney, Hancock) including plan views

- Steamcar history – Some early drawings, plus detail of Verbiest's toy and a related book title...

- Smithsonian library entry for book about model of Verbiest's 'toy'. and Amazon entry for the same book by Horst O. Hardenberg