History of the United Kingdom (1945–present)

| Periods in English history | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

This article gives a political outline of the history of the United Kingdom from the end of the Second World War in 1945, to the present. For coverage of all major topics and a guide to scholarship, see Postwar Britain.

When Britain emerged victorious from World War II, the Labour Party under Clement Attlee came to power and created a comprehensive welfare state, with the establishment of the National Health Service, entitling free healthcare to all British citizens and other reforms included the introduction of old-age pensions, free education at all levels, sickness benefits and unemployment benefits, most of which was covered by the newly introduced national insurance, paid by all workers, this was all under the Beveridge Report. The Bank of England, railways, heavy industry, coal mining and public utilities were all nationalised. During this time, British colonies such as India, Burma and Ceylon gained independence and Britain was a founding member of NATO in 1949.[1][2][3]

The Conservatives returned to power in 1951, accepting most of Labour's postwar reforms (most notably, the National Health Service) and presided over 13 years of economic stability. However the Suez crisis of 1956 arguably ended Britain's status as a superpower. Ghana, Malaya, Nigeria and Kenya were granted independence during this period. Labour returned to power under Harold Wilson in 1964 and oversaw a series of social reforms including the decriminalisation of homosexuality and abortion, the relaxing of divorce laws and the banning of capital punishment. Edward Heath returned the Conservatives to power from 1970 to 1974, and oversaw the decimalisation of British currency, the ascension of Britain to the European Economic Community, and the height of the Troubles in Northern Ireland. In the wake of the oil crisis and a miner's strike, Heath introduced the three-day working week to conserve power.[3][4]

Labour made a return to power in 1974 but a series of strikes carried out by trade unions over the winter of 1978/1979 (known as the Winter of Discontent) paralysed the country and as Labour lost its majority in parliament, a general election was called in 1979 which took Margaret Thatcher to power and began 18 years of Conservative government. Victory in the Falklands War (1982) and the government's strong opposition to trade unions helped lead the Conservative Party to another three terms in government. Thatcher initially pursued monetarist policies and went on to privatise many of Britain's Labour nationalised companies such as BT Group, British gas plc, British Airways and British Steel Corporation. The controversial Community Charge (poll tax), used to fund local government attributed to Thatcher being ousted from her own party and replaced as Prime Minister by John Major in 1990.[5][6]

Major replaced the Poll Tax with the council tax and oversaw British involvement in the Gulf War. Despite a recession, Major led the Conservatives to a surprise victory in 1992. The events of Black Wednesday in 1992, party disunity over the European Union and several scandals involving Conservative politicians led to Labour under Tony Blair winning a landslide election victory in 1997. Labour had shifted its policies closer to the political centre, under the new name 'New Labour'. The Bank of England was given independence over monetary policy and Scotland and Wales were both given a devolved Scottish Parliament and Welsh Assembly respectively. A devolved power sharing Northern Ireland Executive was established in 1998, believed by many to be the end of The Troubles.

Blair led Britain into the controversial Iraq War, which contributed to his eventual resignation in 2007, when he was succeeded by his Chancellor Gordon Brown. A global recession in the late 2000s (decade) led to Labour being defeated in the 2010 election and replaced by a Conservative-Liberal Democrat coalition, headed by David Cameron, that pursued a series of public spending cuts to help reduce Britain's budget deficit.[7] On the 23rd of June 2016 the UK choose to leave the European Union.

Labour Government, 1945–51

Clement Attlee

After World War II, the landslide 1945 election returned the Labour Party to power and Clement Attlee became Prime Minister of the United Kingdom.[8] The party had clear aims. The Bank of England was nationalised along with railroads (see Transport Act 1947), coal mining, public utilities and heavy industry. During this time British Railways was created. A comprehensive welfare state was created with the creation of a National Health Service, entitling all British citizens to healthcare, which, funded by taxation, was free at the point of delivery. Among the most important pieces of legislation was the National Insurance Act 1946, in which people in work paid a flat rate of national insurance. In return, they (and the wives of male contributors) were eligible for flat-rate pensions, sickness benefit, unemployment benefit, and funeral benefit. Various other pieces of legislation provided for child benefit and support for people with no other source of income. Legislation was also passed to provide free education at all levels.[9]

Britain was in many respects unable to afford such radical changes and the government had to cut expenditures. This began with giving independence to many British oversea colonies, beginning with India and Pakistan in 1947, and Burma and Ceylon during 1948–1949. Under the post-war Bretton Woods economic system, Britain had entered into a fixed exchange rate of USD 4.03/ GBP. This rate reflected Britain's sense of its own prestige and economic aspiration and optimism but was badly judged, and hampered economic growth. In 1949, Attlee's government had little choice but to devalue to USD 2.80/ GBP, permanently damaging the administration's credibility.[10]

Despite these problems, one of the main achievements of Attlee's government was the maintenance of near full employment. The government maintained most of the wartime controls over the economy, including control over the allocation of materials and manpower, and unemployment rarely rose above 500,000, or 3% of the total workforce. In fact labour shortages proved to be more of a problem. One area where the government was not quite as successful was in housing, which was also the responsibility of Aneurin Bevan. The government had a target to build 400,000 new houses a year to replace those which had been destroyed in the war, but shortages of materials and manpower meant that less than half this number were built.

Britain became a founding member of the United Nations during this time and also helped found NATO in 1949. During the onset of the Cold War, Britain developed its own nuclear arsenal, although the first test was not carried out until 1952.

In 1948, London hosted the Olympic Games which had originally been planned for 1944 but cancelled due to the war. The event became known as "The Ration Games" due to the lean conditions in Britain at the time. The city was short on funds and a number of cost-cutting measures were undertaken including placing athletes and visiting dignitaries in existing hotels rather than the usual practice of constructing an Olympic Village. The United States and Sweden won the largest share of medals, with the host country finishing in only 12th place with three gold medals, fourteen silver, and six bronze.

The Labour Party was returned to power in the general election of 1950, its share of the popular vote holding up, much to the surprise of some commentators. The large reduction that it suffered in its parliamentary majority was mostly due to the vagaries of the first past the post voting system, plus a degree of Conservative opposition recovering support at the expense of the rapidly declining Liberal Party.[11]

Labour lost the general election of 1951 despite polling more votes than in the 1945 election, and indeed more votes than the Conservative Party.[12]

While the United States with its soil untouched by the war was enjoying prosperity and living standards of a sort never seen before in history, life in postwar Britain was comparatively grim. Living standards and life expectancy were low, there was little for working-class people to buy, and infectious diseases such as tuberculosis continued to claim many lives. Automobile and home ownership were limited to the upper class of society. Birthrates were low compared to the contemporary baby boom in the US. Mandatory military service continued, as despite the end of WWII, Britain continued to wage numerous small conflicts around the globe, in Kenya with the Mau Mau Uprising and the 1956 Suez Canal conflict.

Conservative Government, 1951–64

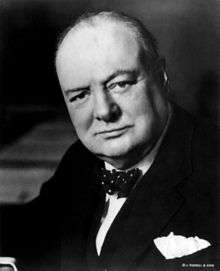

Winston Churchill (1951–55)

Winston Churchill again became Prime Minister. His third government — after the wartime national government and the short caretaker government of 1945 — would last until his resignation in 1955. During this period he renewed what he called the "special relationship" between Britain and the United States, and engaged himself in the formation of the post-war order.

His domestic priorities were, however, overshadowed by a series of foreign policy crises, which were partly the result of the continued decline of British military and imperial prestige and power. Being a strong proponent of Britain as an international power, Churchill would often meet such moments with direct action.

In February 1952, King George VI died and was succeeded by his eldest daughter Elizabeth. Her coronation on 2 June 1953 gave the British people a renewed sense of national pride and enthusiasm which had been lowered by the war. Elizabeth II has now been the monarch for 64 years, 306 days. She celebrated her diamond jubilee, marking 60 years since her ascension to the throne, in 2012.

Anglo-Iranian Oil Dispute

In March 1951, the Iranian parliament (the Majlis) voted to nationalise the Anglo-Iranian Oil Company (AIOC) and its holdings by passing a bill strongly backed by the elderly statesman Mohammed Mossadegh, a man who was elected Prime Minister the following April by a large majority of the parliament. The International Court of Justice was called in to settle the dispute, but a 50/50 profit-sharing arrangement, with recognition of nationalisation, was rejected by Mossadegh. Direct negotiations between the British and the Iranian government ceased, and over the course of 1951, the British ratcheted up the pressure on the Iranian government and explored the possibility of a coup against it. U.S. President Harry S. Truman was reluctant to agree, placing a much higher priority on the Korean War. Churchill's return to power brought with it a policy of undermining the Mossadegh government. Both sides floated proposals unacceptable to the other, each side believing that time was on its side. Negotiations broke down, and as the blockade's political and economic costs mounted inside Iran, coup plots arose from the army and pro-British factions in the Majlis.

The Mau Mau Rebellion

In 1951, grievances against the colonial distribution of land came to a head with the Kenya Africa Union demanding greater representation and land reform. When these demands were rejected, more radical elements came forward, launching the Mau Mau rebellion in 1952. On 17 August 1952, a state of emergency was declared, and British troops were flown to Kenya to deal with the rebellion. As both sides increased the ferocity of their attacks, the country moved to full-scale civil war.

Malayan Emergency

In Malaya, a rebellion against British rule had been in progress since 1948. Once again, Churchill's government inherited a crisis, and once again Churchill chose to use direct military action against those in rebellion while attempting to build an alliance with those who were not. He stepped up the implementation of a "hearts and minds" campaign and approved the creation of fortified villages, a tactic that would become a recurring part of Western military strategy in South-East Asia. (See Vietnam War).

Anthony Eden (1955–57)

Suez crisis

In April 1955, Churchill finally retired, and Sir Anthony Eden succeeded him as Prime Minister. Eden was a very popular figure, as a result of his long wartime service and also his famous good looks and charm. On taking office he immediately called a general election, at which the Conservatives were returned with an increased majority. But Sir Anthony had never held a domestic portfolio and had little experience in economic matters. He left these areas to his lieutenants such as Rab Butler, and concentrated largely on foreign policy, forming a close alliance with US President Dwight Eisenhower.

This alliance proved illusory, however, when in 1956 Sir Anthony, in conjunction with France, tried to prevent Gamal Abdel Nasser, President of Egypt, nationalising the Suez Canal, which had been owned since the 19th century by British and French shareholders in the Suez Canal Company. Sir Anthony, drawing on his experience in the 1930s, saw Nasser as another Mussolini. Sir Anthony considered the two men aggressive nationalist socialists determined to invade other countries. Others believed that Nasser was acting from legitimate patriotic concerns.

In October 1956, after months of negotiation and attempts at mediation had failed to dissuade Nasser, Britain and France, in conjunction with Israel, invaded Egypt and occupied the Suez Canal Zone. But Eisenhower immediately and strongly opposed the invasion. The US President was an advocate of decolonisation, because it would liberate colonies, strengthen US interests, and presumably make other Arab and African leaders more sympathetic to the United States. Also, the Soviet Union threatened to drop nuclear bombs on Paris and/or London unless Britain and France withdrew. Eisenhower feared another global war. When Eden asked for financial help, Eisenhower stated that Britain would have to pull out before the US would provide any more financial aid to Britain. Eden had ignored Britain's financial dependence on the US in the wake of World War II, and was forced to bow to American pressure to withdraw. The crisis arguably marks the end of Britain's status as a superpower, being able to act and control international affairs without assistance or coalition.

Harold Macmillan (1957–63)

Eden resigned in the wake of the Suez Crisis, and his Chancellor of the Exchequer, Harold Macmillan succeeded him as Prime Minister on 10 January. He brought the economic concerns of the exchequer into the premiership, but his approach to the economy was to seek high employment; whereas his treasury ministers argued that to support the Bretton-Wood's requirement on the pound sterling would require strict control of the money base, and hence a rise in unemployment. Their advice was rejected and in January 1958, all the Treasury ministers resigned. Macmillan brushed aside this incident as 'a little local difficulty'.[13]

Macmillan supported the creation of the National Incomes Commission as a means to institute controls on income as part of his growth without inflation policy, a further series of subtle indicators and controls were also introduced during his premiership.

One of Macmillan's more noteworthy actions was the end of conscription. National Service ended gradually from 1957; in November 1960 the last men entered service. With British youth no longer subject to military service and with postwar rationing and reconstruction ended, the stage was set for the social uprisings of the 1960s to commence.

The report The Reshaping of British Railways[14] (or Beeching I report) was published on 27 March 1963. The report starts by quoting the brief provided by the Prime Minister, Harold Macmillan, from 1960 "First, the industry must be of a size and pattern suited to modern conditions and prospects. In particular, the railway system must be modelled to meet current needs, and the modernisation plan must be adapted to this new shape "and with the premise that the railways should be run as a profitable business." It is, of course the responsibility of the British Railways Board so to shape and operate the railways as to make them pay." This led to the notorious Beeching Axe, destroying many miles of permanent way and severing towns from the railway network.

Macmillan also took close control of foreign policy. He worked to narrow the post-Suez rift with the US, where his wartime friendship with Dwight D. Eisenhower was useful, and the two had a pleasant conference in Bermuda as early as March 1957. The amiable relationship remained after the election of President John F. Kennedy.[15] Macmillan also saw the value of a rapprochement with Europe and sought entry to the European Economic Community (EEC) as well as exploring the possibility of an European Free Trade Association (EFTA). In terms of the Empire, Macmillan continued decolonisation, his Wind of Change speech in February 1960 indicating his policy. Ghana and Malaya were granted independence in 1957, Nigeria in 1960 and Kenya in 1963. However, in the Middle East Macmillan ensured Britain remained a force — intervening over Iraq in 1958 (14 July Revolution) and 1960 and becoming involved in Oman. Immigrants from the Commonwealth flocked to England after The British Government posted invitations in the British West Indies, for Workers to come to England to "help the mother Country". He led the Tories to victory in the October 1959 general election, increasing his party's majority from 67 to 107 seats. Following the technical failures of a British independent nuclear deterrent with the Blue Streak and the Blue Steel projects, Macmillan negotiated the supply of American Polaris missiles under the Nassau agreement in December 1962. Previously he had agreed to base sixty Thor missiles in Britain under joint control, and since late 1957 the American McMahon Act had been eased to allow Britain more access to nuclear technology. Britain, the US, and the Soviet Union signed the Partial Test Ban Treaty in autumn 1963. Britain's application to join the EEC was vetoed by French President Charles de Gaulle on 29 January 1963, in due to his fear that 'the end would be a colossal Atlantic Community dependent on America', and personal anger at the Anglo-American nuclear deal.

Britain's balance of payments problems led to the imposition of a seven-month wage freeze in 1961.[16] This caused the government to lose popularity and led to a series of by-election defeats. He organised a major Cabinet change in July 1962 but he continued to lose support from within his party. In 1963, he resigned on 18 October 1963 after he had been diagnosed incorrectly with inoperable prostate cancer. He died 23 years later, in 1986.

Alec Douglas-Home (1963–64)

Macmillan's successor was the Earl of Home, Alec Douglas-Home. However, as no Prime Minister had led from the House of Lords since the Marquess of Salisbury in 1902, Home chose to become a member of parliament so he could enter the House of Commons. He disclaimed his Earldom and, as "Sir Alec Douglas-Home", contested a by-election in the safe seat of Kinross & West Perthshire. Home duly won as (probably) the last peer to become Prime Minister and the only Prime Minister to resign the Lords to enter the Commons. That was his most important claim for entering the history books as his policy was not successful. Following the 1964 general election, the Labour Party was returned to power under Harold Wilson and Home became Leader of the Opposition. In July 1965, Edward Heath defeated Reginald Maudling and Enoch Powell to succeed Home as Conservative Party leader. Enoch Powell was given the post of Shadow Defence Secretary and became a figure of national prominence when he made the controversial Rivers of Blood speech in 1968, warning on the dangers of mass immigration from Commonwealth nations. It is possible that the Conservative's success in the 1970 general election was a result of the large public following Powell attained, even as he was sacked from the shadow cabinet.

Labour Government, 1964–70

Harold Wilson

In 1964, Labour regained the premiership, as Harold Wilson narrowly won the general election with a majority of five. This was not sufficient to last for a full term and, after a short period of competent government, in March 1966, he won re-election with a landslide majority of 99. As Prime Minister, his opponents accused him of deviousness, especially over the matter of devaluation of the pound in November 1967. Wilson had rejected devaluation for many years, yet in his broadcast had seemed to present it as a triumph. During his first period of office, Wilson's government set up the Open University which he would come to regard as his own greatest achievement.

Overseas, Wilson was troubled by crises in several of Britain's former colonies, especially Rhodesia and South Africa. Wilson gave diplomatic support but resisted pressure for military support to the United States in the Vietnam War. In addition to the damage done to its reputation by devaluation, Wilson's Government suffered from the perception that its response to industrial relations problems was inadequate. A six-week strike of members of the National Union of Seamen, which began shortly after Wilson' re-election in 1966, did much to reinforce this perception, along with Wilson's own sense of insecurity in office.

Also during this period, the counterculture movement spread from the US like a wildfire. Although Britain did not experience much of the same social turmoil like the Vietnam War and racial tensions, British youth readily identified with their American counterparts' desire to cast off the older generation's social mores. In this case, it took the form of a wholesale revolt against the class system, which was now being questioned for the first time in the nation's history. Rock music, which had first been introduced from the US in the 1950s, became a key instrument in the social uprisings of the young generation and Britain soon became a groundswell of musical talent thanks to groups like the Beatles, Rolling Stones, The Who, Pink Floyd, and more in coming years.

On 16 February 1965, Lord Beeching announced the second stage of his reorganisation of the railways. In The Development of the Major Railway Trunk Routes.[17] In this report he set out his conclusion that of the 7,500 miles (12,100 km) of trunk railway only 3,000 miles (4,800 km) "should be selected for future development" and invested in.

Conservative Government, 1970–74

Edward Heath

The premiership of his successor Sir Edward Heath was the bloodiest in the history of the Northern Ireland Troubles. He was prime minister at the time of Bloody Sunday in 1972 when 14 unarmed men were killed by British soldiers during a banned civil rights march in Derry. In 2003, he gave evidence to the Saville Inquiry and claimed that he never promoted or agreed to the use of unlawful lethal force in Northern Ireland. In July 1972, he permitted his Secretary of State for Northern Ireland William Whitelaw to hold unofficial talks in London with a Provisional Irish Republican Army delegation by Seán Mac Stiofáin. In the aftermath of these unsuccessful talks, the Heath government pushed for a peaceful settlement with the democratic political parties. In 1974, the Sunningdale Agreement was produced but fiercely repudiated by many Unionists and the Ulster Unionist Party ceased to support the Conservatives at Westminster.

Heath's major achievement as prime minister was to take Britain into the European Economic Community on 1 January 1973. Meanwhile, on the domestic front, galloping inflation led him into confrontation with some of the most powerful trade unions, and energy shortages related to the oil shock resulted in much of the country's industry working a Three-Day Week to conserve power. In an attempt to bolster his government, Heath called an election for 28 February 1974. The result was inconclusive: the Conservative Party received a plurality of votes cast, but the Labour Party gained a plurality of seats due to the Ulster Unionist MPs refusing to support the Conservatives. Heath began negotiations with leaders of the Liberal Party to form a coalition, but, when these failed, resigned as Prime Minister.

Labour Government, 1974–79

Harold Wilson (1974–76)

Heath was replaced by Harold Wilson, who returned on 4 March 1974 to form a minority government. Wilson was confirmed in office, with a three-seat majority, in a second election in October of the same year.[18] It was a manifesto pledge in the general election of February 1974 for a Labour government to re-negotiate better terms for Britain in the EEC, and then hold a referendum on whether Britain should stay in the EEC on the new terms. After the House of Commons voted in favour of retaining the Common Market on the renegotiated terms, a referendum was held on 5 June 1975. A majority were in favour of retaining the Common Market.[19] But WIlson was not able to end the economic crisis. Unemployment remained well in excess of 1,000,000, inflation peaked at 24% in 1975, and the national debt was increasing. The rise of punk rock bands such as the Sex Pistols and The Clash were a reflection of the discontent felt by British youth during the difficulties of the late 1970s.

James Callaghan (1976–79)

Wilson announced his surprise resignation on 16 March 1976 and unofficially endorsed his Foreign Secretary James Callaghan as his successor. His popularity with all parts of the Labour movement saw him through the ballot of Labour MPs. Callaghan was the first Prime Minister to have held all three leading Cabinet positions — Chancellor of the Exchequer, Home Secretary and Foreign Secretary — prior to becoming Prime Minister.[20]

Callaghan's support for and from the union movement should not be mistaken for a left wing position. Callaghan continued Wilson's policy of a balanced Cabinet and relied heavily on the man he defeated for the job of party leader — the arch-Bevanite Michael Foot. Foot was made Leader of the House of Commons and given the task of steering through the government's legislative programme.

Callaghan's time as Prime Minister was dominated by the troubles in running a Government with a minority in the House of Commons; by-election defeats had wiped out Labour's three-seat majority by early 1977. Callaghan was forced to make deals with minor parties in order to survive, including the Lib-Lab pact. He had been forced to accept referendums on devolution in Scotland and Wales (the first went in favour but did not reach the required majority, and the second went heavily against).

However, by the autumn of 1978 the economy was showing signs of recovery – although unemployment now stood at 1,500,000, economic growth was strong and inflation had fallen below 10%.[21] Most opinion polls were showing Labour ahead and he was expected to call an election before the end of the year. His decision not to has been described as the biggest mistake of his premiership.

Callaghan's way of dealing with the long-term economic difficulties involved pay restraint which had been operating for four years with reasonable success. He gambled that a fifth year would further improve the economy and allow him to be re-elected in 1979, and so attempted to hold pay rises to 5% or less. The Trade Unions rejected continued pay restraint and in a succession of strikes over the winter of 1978/79 (known as the Winter of Discontent) secured higher pay, although it had virtually paralysed the country, tarnished Britain's political reputation and seen the Conservatives surge ahead in the opinion polls.[22][23]

He was forced to call an election when the House of Commons passed a Motion of No Confidence by one vote on 28 March 1979. The Conservatives, with advertising consultants Saatchi and Saatchi, ran a campaign on the slogan "Labour isn't working." As expected, Margaret Thatcher (who had succeeded Edward Heath as Conservative leader in February 1975) won the general election held on 3 May, becoming Britain's first female prime minister.

Historian Kenneth Morgan states:

- The fall of James Callahan in the summer of 1979 meant, according to most commentators across the political spectrum, the end of an ancien régime, a system of corporatism, Keynesian spending programmes, subsidized welfare, and trade union power.[24]

Historians Alan Sked and Chris Cook have summarized the general consensus of historians regarding Labour in power in the 1970s:

- If Wilson's record as prime minister was soon felt to have been one of failure, that sense of failure was powerfully reinforced by Callahan's term as premier. Labour, it seemed, was incapable of positive achievements. It was unable to control inflation, unable to control the unions, unable to solve the Irish problem, unable to solve the Rhodesian question, unable to secure its proposals for Welsh and Scottish devolution, unable to reach a popular modus vivendi with the Common Market, unable even to maintain itself in power until it could go to the country and the date of its own choosing. It was little wonder, therefore, that Mrs. Thatcher resoundingly defeated it in 1979.[25]

Conservative Government, 1979–97

Margaret Thatcher (1979–90)

Thatcher formed a government on 4 May 1979, with a mandate to reverse the UK's economic decline and to reduce the role of the state in the economy. Thatcher was incensed by one contemporary view within the Civil Service that its job was to manage the UK's decline from the days of Empire, and wanted the country to punch above its weight in international affairs. She was a philosophic soulmate with Ronald Reagan, elected in 1980 in the United States, and to a lesser extent, Brian Mulroney, who was elected in 1984 in Canada. It seemed for a time that conservatism might be the dominant political philosophy in the major English-speaking nations for the era.

Irish issues

In May 1980, one day before she was due to meet the Irish Taoiseach, Charles Haughey to discuss Northern Ireland, she announced in the House of Commons that "The future of the constitutional affairs of Northern Ireland is a matter for the people of Northern Ireland, this government, this Parliament and no-one else."

In 1981, a number of Provisional IRA and Irish National Liberation Army prisoners in Northern Ireland's Maze prison went on hunger strike to regain the status of political prisoners, which had been revoked five years earlier. After 10 men had starved themselves to death and the strike had ended political status was restored to all paramilitary prisoners. This was a major propaganda coup for the IRA and is seen as the beginning of Sinn Féin's electoral rise, as they capitalised on the gains made during the hunger strikes.

Thatcher continued the policy of "Ulsterisation" of the previous Labour government and its Secretary of State for Northern Ireland, Roy Mason, believing that the unionists of Ulster should be at the forefront in combating Irish republicanism. This meant relieving the burden on the mainstream British army and elevating the role of the Ulster Defence Regiment and the Royal Ulster Constabulary.

Sheer luck on the early morning of 12 October 1984 saved Thatcher's life in the bomb planted by the Provisional Irish Republican Army in Brighton's Grand Hotel during the Conservative Party conference. Five people died in the attack.

On 15 November 1985, Thatcher signed the Hillsborough Anglo-Irish Agreement, the first acknowledgement by a British government that the Republic of Ireland had an important role to play in Northern Ireland. The agreement was greeted with fury by Irish unionists. The Ulster Unionists and Democratic Unionists made an electoral pact and on 23 January 1986, staged an ad-hoc referendum by re-fighting their seats in by-elections, and won with one seat lost to the nationalist Social Democratic and Labour Party (SDLP). Then, unlike the Sunningdale Agreement in 1974, they found they could not bring the agreement down by a general strike. This was another effect of the changed balance of power in industrial relations. The agreement stood, and Thatcher "punished" the unionists for their non-cooperation by abolishing a devolved assembly she had created only four years before, although unionists have traditionally been of two minds about political devolution (witness the "Home Rule" crisis that led to the Anglo-Irish War), and the politicians most affected by the abolishment of the assembly were the constitutional nationalists, i.e., the SDLP, not Sinn Féin, which was not interested in a devolved assembly at that time, nor would it be for many years to come. The Anglo-Irish Agreement therefore, enraged the Unionists and alienated moderate nationalists, while doing little to reduce IRA violence. The British Government's intention may have been to solidify support from Dublin. However, the British Government had proved an unreliable ally since Éamon de Valera's time, adopting the strategy of making conciliatory gestures or minor concessions with one hand and undermining Ireland with the other.

Diana

During the summer of 1981, the nation's spirits were raised by the wedding of Prince Charles and Lady Diana Spencer. The globally-televised ceremony, also brought the royal family, which had been almost forgotten by most of the general public, back into the headlines where they would become a permanent fixture in tabloids and celebrity gossip publications.

Economics

In economic policy, Thatcher started out by increasing interest rates to drive down the money supply. She had a preference for indirect taxation over taxes on income, and value added tax (VAT) rose sharply to 15% with the result that inflation also rose. These moves hit businesses, especially in the manufacturing sector, and unemployment – which had stood at 1,500,000 by the time of the 1979 general election – was above 2,000,000 by the end of 1980. It continued to rise throughout 1981, passing the 2,500,000 mark during the summer of that year – although inflation was now down to 12% compared to 27% two years earlier. The economy was now in recession.

Her early tax policy reforms were based on the monetarist theories of Friedman rather than the supply-side economics of Arthur Laffer and Jude Wanniski, which the government of Ronald Reagan espoused. There was a severe recession in the early 1980s, and the Government's economic policy was widely blamed. In January 1982, the inflation rate dropped to single figures and interest rates were then allowed to fall. Unemployment continued to rise, peaking at a figure of more than 3.2 million[26] (estimated by the International Labour Organization). Despite the preference of most UK Governments to use the smaller figure of claimant count, this number itself exceeded 3,000,000 by early 1982.[27] The recession of the early 1980s was the deepest in Britain since the depression of the 1930s and Thatcher's popularity plummeted with most predicting she would lose the next election.

Falklands

In Argentina, an unstable military junta was in power and keen on reversing its huge economic unpopularity. On 2 April 1982, it invaded the Falkland Islands, the only invasion of a British territory since World War II. Argentina has claimed the islands since an 1830s dispute on their settlement. Thatcher sent a naval task force to recapture the Islands. The ensuing military campaign saw the swift defeat of Argentina in only a few days of fighting, resulting in a wave of patriotic enthusiasm for her personally, at a time when her popularity had been at an all-time low for a serving Prime Minister. Opinion polls showed a huge surge in Conservative support which would be sufficient to win a general election.

One British destroyer had been sunk by an Argentine vessel armed with a French Exocet missile launcher, an event that disturbed relations with Paris for some months, but by the end of the year, the storm clouds had mostly blown away.

This "Falklands Factor", as it came to be known, was crucial to the scale of the Conservative majority in the June 1983 general election, with a fragmented Labour Party enduring its worst postwar election result, while the SDP-Liberal Alliance (created two years earlier in a pact between the Liberal Party and the new Social Democratic Party (UK) formed by disenchanted former Labour MP's) trailed Labour closely in terms of votes if not seats.

Hong Kong

China demanded the return of Hong Kong with the expiration of Britain's 99-year lease on most of the territory in 1997. Thatcher negotiated directly in September 1982 with that country's leader Deng Xiaoping. They agreed on the Sino-British Joint Declaration over the Question of Hong Kong which provided for a peaceful transfer of Hong Kong to Beijing's control in 15 years' time, after which the city would be allowed to retain its "capitalistic" system for another 50 years.

Thatcher's strong opposition against communism and the Soviet Union as well as the decisive military victory against Argentina, re-affirmed Britain's influential position on the world stage and bolstered Thatcher's firm leadership. In addition the economy was showing positive signs of recovery thanks mainly to substantial oil revenues from the North Sea. Also despite mass unemployment, it was implied to be transitory, and alongside it new laws had given trade union members democratic powers to restrain militant union leaderships. Additionally, Thatcher's 'Right to Buy' policy, whereby council housing residents were permitted to buy their homes at a discount did much to increase her government's popularity in working-class areas.

Thatcher was angry at the US invasion of Grenada in 1983, but supported the American move.

Nuclear disarmament

The 1983 election was also influenced by events in the opposition parties. Since their 1979 defeat, Labour was increasingly dominated by its "hard left" that had emerged from the 1970s union militancy, and in opposition its policies had swung very sharply to the left while the Conservatives had drifted further to the right. This drove a significant number of right wing Labour members and MPs to form a breakaway party in 1981, the Social Democratic Party. Labour fought the election on unilateral nuclear disarmament, which proposed to abandon the British nuclear deterrent despite the threat from a nuclear armed Soviet Union, withdrawal from the European Community, and total reversal of Thatcher's economic and trade union changes. Indeed, one Labour MP, Gerald Kaufman, has called the party's 1983 manifesto "the longest suicide note in history". Consequently, upon the Labour split, there was a new centrist challenge, the Alliance, from the Social Democrats in electoral pact with the Liberal Party, to break the major parties' dominance and win proportional representation. The British Electoral Study found that Alliance voters were preferentially tilted towards the Conservatives , but this possible loss of vote share by the Conservatives was more than compensated for by the first past the post electoral system, where marginal changes in vote numbers and distribution have disproportionate effects on the number of seats won. Accordingly, despite the Alliance vote share coming very close to that of Labour and preventing an absolute majority in votes for the Conservatives, the Alliance failed to break into Parliament in significant numbers and the Conservatives were returned in a landslide.

Trade union power

Thatcher was committed to reducing the power of the trade unions but, unlike the Heath government, adopted a strategy of incremental change rather than a single Act. Several unions launched strikes that were wholly or partly aimed at damaging her politically. The most significant of these was carried out by the National Union of Mineworkers (NUM). However, Thatcher had made preparations long in advance for an NUM strike by building up coal stocks, and there were no cuts in electric power, unlike 1972. Police tactics during the strike concerned civil libertarians: stopping suspected strike sympathisers travelling towards coalfields when they were still long distances from them, phone tapping as evidenced by Labour's Tony Benn, and a violent battle with mass pickets at Orgreave, Yorkshire. But images of massed militant miners using violence to prevent other miners from working, along with the fact that (illegally under a recent Act) the NUM had not held a national ballot to approve strike action. Scargill's policy of letting each region of the NUM call its own strike backfired when nine areas held ballots that resulted in majority votes against striking,[28] and violence against strikebreakers escalated with time until reaching a tipping point with the killing of David Wilkie (a taxi-driver who was taking a strikebreaker to work). The Miners' Strike lasted a full year, March 1984 until March 1985, before the drift of half the miners back to work forced the NUM leadership to give in without a deal. Thatcher had won a decisive victory and the unions never recovered their political power. This aborted political strike marked a turning point in UK politics: no longer could militant unions remove a democratically elected government. It also marked to beginning of a new economic and political culture in the UK based upon small government intervention in the economy and reduced dominance of the trade unions and welfare state.

Thatcher's political and economic philosophy emphasised free markets and entrepreneurialism. Since gaining power, she had experimented in selling off a small nationalised company, the National Freight Company, to its workers, with a surprisingly large response. After the 1983 election, the Government became bolder and sold off most of the large utilities which had been in public ownership since the late 1940s. Many in the public took advantage of share offers, although many sold their shares immediately for a quick profit. The policy of privatisation, while anathema to many on the left, has become synonymous with Thatcherism.

In the Cold War, Mrs. Thatcher supported Ronald Reagan's policies of deterrence against the Soviets. This contrasted with the policy of détente which the West had pursued during the 1970s, and caused friction with allies still wedded to the idea of détente. US forces were permitted by Mrs. Thatcher to station nuclear cruise missiles at British bases, arousing mass protests by the Campaign for Nuclear Disarmament. However, she later was the first Western leader to respond warmly to the rise of reformist Soviet leader Mikhail Gorbachev, declaring she liked him and "We can do business together" after a meeting three months before he came to power in 1985. This was a start in swinging the West back to a new détente with the Soviet Union in his era, as it proved to be an indication that the Soviet regime's power was decaying. Thatcher outlasted the Cold War, which ended in 1989, and voices who share her views on it credit her with a part in the West's victory, by both the deterrence and détente postures.

She supported the US bombing raid on Libya from bases in the UK in 1986 when other NATO allies would not. Her liking for defence ties with the United States was demonstrated in the Westland affair when she acted with colleagues to prevent the helicopter manufacturer Westland, a vital defence contractor, from linking with the Italian firm Agusta in favour of a link with Sikorsky Aircraft Corporation of the United States. Defence Secretary Michael Heseltine, who had pushed the Agusta deal, resigned in protest at her style of leadership, and thereafter became a potential leadership challenger.

In 1986, the government controversially abolished the Greater London Council (GLC), then led by left-winger Ken Livingstone and six Metropolitan County Councils (MCCs). The government claimed this was an efficiency measure. However, it is widely believed to have been politically motivated, as all of the abolished councils were controlled by Labour, and had become powerful centres of opposition to her government and were in favour of higher public spending by local government.

By winning the 1987 general election, on the economic boom (with unemployment finally falling below 3,000,000 that spring) and against a stubbornly anti-nuclear Labour opposition (now led by Neil Kinnock after Michael Foot's resignation four years earlier), she became the longest serving Prime Minister of the United Kingdom since Lord Liverpool (1812–1827), and first to win three successive elections since Lord Palmerston in 1865. Most United Kingdom newspapers supported her — with the exception of The Daily Mirror and The Guardian — and were rewarded with regular press briefings by her press secretary, Bernard Ingham. She was known as "Maggie" in the tabloids, which inspired the well-known "Maggie Out!" protest song, sung throughout that period by some of her opponents. Her unpopularity on the left is evident from the lyrics of several contemporary popular songs: "Stand Down Margaret" (The Beat), "Tramp the Dirt Down" (Elvis Costello), "Mother Knows Best" (Richard Thompson), and "Margaret on the Guillotine" (Morrissey).

Many opponents believed she and her policies created a significant North-South divide from the Bristol Channel to The Wash, between the "haves" in the economically dynamic south and the "have nots" in the northern rust belt. Hard welfare reforms in her third term created an adult Employment Training system that included full-time work done for the dole plus a £10 top-up, on the workfare model from the US. The "Social Fund" system that placed one-off welfare payments for emergency needs under a local budgetary limit, and where possible changed them into loans, and rules for assessing jobseeking effort by the week, were breaches of social consensus unprecedented since the 1920s.

The sharp fall in unemployment continued as the end of the decade neared. By the end of 1987, it stood at just over 2,600,000 – having started the year still in excess of 3,000,000. It stood at just over 2,000,000 by the end of 1988, and by the end of 1989 less than 1,700,000 were unemployed. However, total economic growth for 1989 stood at 2% – the lowest since 1982 – signalling an end to the economic boom. Several other countries had now entered recession, and fears were now rife that Britain was also on the verge of another recession.[29]

In the late 1980s, Thatcher, a former chemist, became concerned with environmental issues, which she had previously ignored. In 1988, she made accepting the problems of global warming, ozone depletion and acid rain.[30] In 1990, she opened the Hadley Centre for climate prediction and research.[31]

At Bruges, Belgium in 1988, Thatcher made a speech in which she outlined her opposition to proposals from the European Community for a federal structure and increasing centralisation of decision-making. Although she had supported British membership, Thatcher believed that the role of the EC should be limited to ensuring free trade and effective competition, and feared that new EC regulations would reverse the changes she was making in the UK. "We have not successfully rolled back the frontiers of the state in Britain, only to see them re-imposed at a European level, with a new super-state exercising a new dominance from Brussels". She was specifically against Economic and Monetary Union, through which a single currency would replace national currencies, and for which the EC was making preparations. The speech caused an outcry from other European leaders, and exposed for the first time the deep split that was emerging over European policy inside her Conservative Party.

Thatcher's popularity once again declined in 1989 as the economy suffered from high interest rates imposed to stop an unsustainable boom. She blamed her Chancellor, Nigel Lawson, who had been following an economic policy which was a preparation for monetary union; Thatcher claimed not to have been told of this and did not approve. At the Madrid European summit, Lawson and Foreign Secretary Geoffrey Howe forced Thatcher to agree the circumstances under which she would join the Exchange Rate Mechanism, a preparation for monetary union. Thatcher took revenge on both by demoting Howe, and by listening more to her adviser Sir Alan Walters on economic matters. Lawson resigned that October, feeling that Thatcher had undermined him.

That November, Thatcher was challenged for the leadership of the Conservative Party by Sir Anthony Meyer. As Meyer was a virtually unknown backbench MP, he was viewed as a stalking horse candidate for more prominent members of the party. Thatcher easily defeated Meyer's challenge, but there were 60 ballot papers either cast for Meyer or abstaining, a surprisingly large number for a sitting Prime Minister.

Thatcher's new system to replace local government rates was introduced in Scotland in 1989 and in England and Wales in 1990. Rates were replaced by the "Community Charge" (more widely known as the poll tax), which applied the same amount to every individual resident, with only limited discounts for low earners. This was to be the most universally unpopular policy of her premiership, and saw the Conservative government split further behind the Labour opposition (still led by Neil Kinnock) in the opinion polls. The Charge was introduced early in Scotland as the rateable values would in any case have been reassessed in 1989. However, it led to accusations that Scotland was a 'testing ground' for the tax. Thatcher apparently believed that the new tax would be popular, and had been persuaded by Scottish Conservatives to bring it in early and in one go. Despite her hopes, the early introduction led to a sharp decline in the already low support for the Conservative party in Scotland.

Additional problems emerged when many of the tax rates set by local councils proved to be much higher than earlier predictions. Some have argued that local councils saw the introduction of the new system of taxation as the opportunity to make significant increases in the amount taken, assuming (correctly) that it would be the originators of the new tax system and not its local operators who would be blamed.

A large London demonstration against the poll tax on 31 March 1990 — the day before it was introduced in England and Wales — turned into a riot. Millions of people resisted paying the tax. Opponents of the tax banded together to resist bailiffs and disrupt court hearings of poll tax debtors. Mrs Thatcher refused to compromise, or change the tax, and its unpopularity was a major factor in Thatcher's downfall.

By the autumn of 1990, opposition to Thatcher's policies on local government taxation, her Government's perceived mishandling of the economy (especially high interest rates of 15%, which were undermining her core voting base within the home-owning, entrepreneurial and business sectors), and the divisions opening within her party over the appropriate handling of European integration made her and her party seem increasingly politically vulnerable. Her increasingly combative, irritable personality also made opposition to her grow fast and by this point, even many in her own party could not stand her.

John Major (1990–97)

In November 1990, Michael Heseltine challenged Margaret Thatcher for leadership of the Conservative Party. Thatcher failed to gain enough votes for a majority in the first round and thus withdrew from the second round on 22 November, ending her 11-year premiership. Chancellor of the Exchequer John Major contested the second round and defeated Michael Heseltine as well as Foreign Secretary Douglas Hurd, becoming prime minister on 27 November 1990.[32]

By this stage, however, Britain had slid into recession for the third time in less than 20 years. Unemployment had started to rise in the spring of 1990 but by the end of the year it was still lower than in many other European economies, particularly France and Italy.

John Major was Prime Minister during British involvement in the Gulf War and he and The change of prime minister from Margaret Thatcher to John Major saw a turnaround in Conservative fortunes in the opinion polls, with the Conservatives managing to top many opinion polls over the next 17 months as a general election loomed. This was despite the recession deepening throughout 1991 and into 1992, with the economy for 1991 detracted by 2% and unemployment passing the 2,000,000 mark.[33]

Major called a general election for April 1992 and took his campaign onto the streets, famously delivering many addresses from an upturned soapbox as in his Lambeth days. This populist "common touch", in contrast to the Labour Party's more slick campaign, chimed with the electorate and Major won an unexpected second period in office, albeit with a small parliamentary majority. The Conservative election win was something of a surprise to the pollsters, who had predicted a hung parliament or a narrow Labour win.[34]

The narrow majority for the Conservative government proved to be unmanageable, particularly after the United Kingdom's forced exit from the Exchange Rate Mechanism on Black Wednesday (16 September 1992) just five months into the new parliament. From this stage onwards, Labour – now led by John Smith – was ascendant in the opinion polls. Major allowed his economic team to stay in place unchanged for seven months after Black Wednesday before forcing the resignation of his Chancellor, Norman Lamont, who he replaced with Kenneth Clarke. This delay was indicative of one of his weaknesses, an indecisiveness towards personnel issues that was to undermine his authority through the rest of his premiership.[35]

At the 1993 Conservative Party Conference, Major began his ill-fated "Back to Basics" campaign, which he intended to be about the economy, education, policing, and other such issues, but it was interpreted by many (including Conservative cabinet ministers) as an attempt to revert to the moral and family values that the Conservative Party were often associated with. A number of sleaze scandals involving Conservative MP's were exposed in lurid and embarrassing detail in tabloid newspapers following this and further reduced the Conservative's popularity. Despite Major's best efforts, the Conservative Party collapsed into political infighting. Major took a moderate approach but found himself undermined by the right-wing within the party and the Cabinet. In particular, his policy towards the European Union aroused opposition as the Government attempted to ratify the Maastricht Treaty. Although the Labour opposition supported the treaty, they were prepared to undertake tactical moves to weaken the government, which included passing an amendment that required a vote on the social chapter aspects of the treaty before it could be ratified. Several Conservative MPs (the Maastricht Rebels) voted against the Government and the vote was lost. Major hit back by calling another vote on the following day (23 July 1993), which he declared a vote of confidence. He won by 40 but had damaged his authority.[35]

One of the few bright spots of 1993 for the Conservative government came in April when the end of the recession was finally declared after nearly three years. Unemployment had touched 3,000,000 by the turn of the year, but had dipped to 2,800,000 by Christmas as the economic recovery continued. The economic recovery was strong and sustained throughout 1994, with unemployment falling below 2,500,000 by the end of the year. However, Labour remained ascendant in the opinion polls and their popularity further increased with the election of Tony Blair – who redesignated the party as New Labour – as leader following the sudden death of John Smith on 12 May 1994.[36] Labour remained ascendant in the polls throughout 1995, despite the Conservative government overseeing the continuing economic recovery and fall in unemployment.[37] It was a similar story throughout 1996, despite the economy still being strong and unemployment back below 2,000,000 for the first time since early 1991.[38] The Railways Act 1993 [39] (1993 c. 43) was introduced by John Major's Conservative government and passed on 5 November 1993. It provided for the restructuring of the British Railways Board (BRB), the public corporation that owned and operated the national railway system. A few residual responsibilities of the BRB remained with BRB (Residuary) Ltd.

Few were surprised when Major lost the 1997 general election to Tony Blair, though the immense scale of the defeat was not widely predicted. In the new parliament Labour won 418 seats, the Conservatives 165, and the Liberal Democrats 46, leaving the Labour party with a majority of 179 which was the biggest majority since 1931. In addition, the Conservatives lost all their seats in Scotland and Wales and several cabinet ministers including Norman Lamont, Michael Portillo, Malcolm Rifkind and Ian Lang lost their seats. Major carried on as Leader of the Opposition until William Hague was elected to lead the Conservative Party the month after the election.[40]

Labour Government, 1997–2010

Tony Blair (1997–2007)

Tony Blair became Prime Minister in 1997 after a landslide victory over the Conservative Party. Under the title of New Labour, he promised economic and social reform and brought Labour closer to the center of the political spectrum. Early policies of the Blair government included the minimum wage and university tuition fees. Chancellor of the Exchequer Gordon Brown also gave the Bank of England the power to set the base rate of interest autonomously. The traditional tendency of governments to manipulate interest rates around the time of general elections for political gain is thought to have been deleterious to the UK economy and helped reinforce a cyclical pattern of boom and bust. Brown's decision was popular with the City, which the Labour Party had been courting since the early 1990s. Blair presided over the longest period of economic expansion in Britain since the 19th century and his premiership saw large investment into social aspects, in particular health and education, areas particularly under-invested during the Conservative government of the 1980s and early 1990s. The Human Rights Act was introduced in 1998 and the Freedom of Information Act came into force in 2000. Most hereditary peers were removed from the House of Lords in 1999 and the Civil Partnership Act of 2005 allowed homosexual couples the right to register their partnership with the same rights and responsibilities comparable to heterosexual marriage.

The nation was stunned when Princess Diana died in a car accident in Paris on 31 August 1997, even though she had divorced Prince Charles a few years earlier. Numerous conspiracy theories arose about her being intentionally murdered due to her plans to marry an Arab businessman, although nothing was ever proven.

From the beginning, New Labour's record on the economy and unemployment was strong, suggesting that they could break with the trend of Labour governments overseeing an economic decline while in power. They had inherited an unemployment count of 1,700,000 from the Conservatives, and by the following year unemployment was down to 1,300,000 – a level not seen since James Callaghan was in power some 20 years previously. A minimum wage was announced in May 1998, coming into force from April 1999.[41] Unemployment would remain similarly low for the next 10 years.[42]

The long-running Northern Ireland peace process was brought to a conclusion in 1998 with the Belfast Agreement which established a devolved Northern Ireland Assembly and de-escalated the violence associated with the Troubles. It was signed in April 1998 by the British and Irish governments and was endorsed by all the main political parties in Northern Ireland with the exception of Ian Paisley's Democratic Unionist Party. Voters in Northern Ireland approved the agreement in a referendum in May 1998 and it came into force in December 1999. In August 1998, a car-bomb exploded in the Northern Ireland town of Omagh, killing 29 people and injuring 220. The attack was carried out by the Real Irish Republican Army who opposed the Belfast Agreement. It was reported in 2005, that the IRA had renounced violence and had ditched its entire arsenal.

In foreign policy, following the September 11, 2001 attacks in the United States, Blair greatly supported U.S. President George W. Bush's new War on Terror which began with the forced withdrawal of the Taliban regime in Afghanistan. Blair's case for war was based on Iraq's alleged possession of weapons of mass destruction and consequent violation of UN resolutions. He was wary of making direct appeals for regime change, since international law does not recognise this as a ground for war. A memorandum from a July 2002 meeting that was leaked in April 2005 showed that Blair believed that the British public would support regime change in the right political context; the document, however, stated that legal grounds for such action were weak. On 24 September 2002 the Government published a dossier based on the intelligence agencies' assessments of Iraq's weapons of mass destruction. Among the items in the dossier was a recently received intelligence report that "the Iraqi military are able to deploy chemical or biological weapons within 45 minutes of an order to do so". A further briefing paper on Iraq's alleged WMDs was issued to journalists in February 2003. This document was discovered to have taken a large part of its text without attribution from a PhD thesis available on the internet. Where the thesis hypothesised about possible WMDs, the Downing Street version presented the ideas as fact. The document subsequently became known as the "Dodgy Dossier".

46,000 British troops, one-third of the total strength of the British Army (land forces), were deployed to assist with the invasion of Iraq. When after the war, no WMDs were found in Iraq, the two dossiers, together with Blair's other pre-war statements, became an issue of considerable controversy. Many Labour Party members, including a number who had supported the war, were among the critics. Successive independent inquiries (including those by the Foreign Affairs Select Committee of the House of Commons, the senior judge Lord Hutton, and the former senior civil servant Lord Butler of Brockwell) have found that Blair honestly stated what he believed to be true at the time, though Lord Butler's report did imply that the Government's presentation of the intelligence evidence had been subject to some degree of exaggeration. These findings have not prevented frequent accusations that Blair was deliberately deceitful, and, during the 2005 election campaign, Conservative leader Michael Howard made political capital out of the issue. The new threat of international terrorism ultimately led to the 7 July 2005 bomb attacks in London which killed 52 people as well as the four suicide bombers who led the attack.

The Labour government was re-elected with a second successive landslide in the general election of June 2001.[43] Blair became the first Labour leader to lead the party to three successive election victories when they won the 2005 general election, though this time he had a drastically reduced majority.[44]

The Conservatives had so far failed to represent a serious challenge to Labour's rule, with John Major's successor William Hague unable to make any real improvement upon the disastrous 1997 general election result at the next election four years later. He stepped down after the 2001 election to be succeeded by Iain Duncan Smith, who did not even hold the leadership long enough to contest a general election – being ousted by his own MP's in October 2003[45] and being replaced by Michael Howard, who had served as Home Secretary in the government of John Major. Howard failed to win the 2005 general election for the Conservatives but he at least had the satisfaction of narrowing the Labour majority, giving his successor (he announced his resignation shortly after the election) a decent platform to build upon.[46] However, the Conservatives began to re-emerge as an electable prospect following the election of David Cameron as Howard's successor in December 2005. Within months of Cameron becoming Conservative leader, opinion polls during 2006 were showing a regular Conservative lead for the first time since Black Wednesday 14 years earlier. Despite the economy still being strong and unemployment remaining low, Labour's decline in support was largely blamed upon poor control of immigration and allowing Britain to become what was seen by many as an easy target for terrorists.[47]

Devolution for Scotland and Wales

Blair also came into power with a policy of devolution. A pre-legislative referendum was held in Scotland in 1997 with two questions: whether to create a devolved Parliament for Scotland and whether it should have limited tax-varying powers. Following a clear 'yes' vote on both questions, a referendum on the proposal for creating a devolved Assembly was held two weeks later. This produced a narrow 'yes' vote. Both measures were put into effect and the Scottish Parliament and Welsh Assembly began operating in 1999. The first election to the Scottish parliament saw the creation of a Labour-Liberal Democrat coalition with Donald Dewar as First Minister. In Wales, the Labour Party achieved a complete majority with Alun Michael as the Welsh First Minister. In the 2007 Scottish election, the Scottish National Party gained enough seats to form a minority government with its leader Alex Salmond as First Minister.

Devolution also returned to Northern Ireland, leaving England as the only constituent country of the United Kingdom without a devolved administration. Within England, a devolved authority for London was re-established following a 'yes' vote in a London-wide referendum.

On 18 September 2014, a referendum on Scottish independence failed with a 55/44 percentage.

Gordon Brown (2007–10)

Tony Blair tendered his resignation as Prime Minister of the United Kingdom to the Queen on 27 June 2007, his successor Gordon Brown assuming office the same afternoon. Gordon Brown took over as Prime Minister without having to face either a general election or even a contested election for leadership of the Labour Party.

Brown's style of government differed from that of his predecessor, Tony Blair, who had been seen as presidential. Brown rescinded some of the policies which had either been introduced or were planned by Blair's administration. He remained committed to close ties with the United States and to the Iraq war, although he established an inquiry into the reasons why Britain had participated in the conflict. He proposed a "government of all the talents" which would involve co-opting leading personalities from industry and other professional walks of life into government positions. Brown also appointed Jacqui Smith as the UK's first female Home Secretary, while Brown's old position as Chancellor was taken over by Alistair Darling.

His appointment as prime minister sparked a brief surge in Labour support as the party topped most opinion polls that autumn. There was talk of a "snap" general election, which it was widely believed Labour could win, but Brown decided against calling an election.[48]

Brown's government introduced a number of fiscal policies to help keep the British economy afloat during the financial crisis which occurred throughout the latter part of the 2000s (decade) and early 2010, although the United Kingdom saw a dramatic increase in its national debt. Unemployment soared through 2008 as the recession set in, and Labour standings in the opinion polls plummeted as the Conservatives became ascendant.[49]

Several major banks were nationalised after falling into financial difficulties, while large amounts of money were pumped into the economy to encourage spending. Brown was also press ganged into giving Gurkhas settlement rights in Britain by the actress and campaigner Joanna Lumley and attracted criticism for its handling of the release of Abdelbaset Al Megrahi, the only person to have been convicted over the 1988 Lockerbie bombing.

Initially, during the first four months of his premiership, Brown enjoyed a solid lead in the polls. His popularity amongst the public may be due to his handling of numerous serious events during his first few weeks as Prime Minister, including two attempted terrorist attacks in London and Glasgow at the end of June. However, between the end of 2007 and September 2008, his popularity had fallen significantly, with two contributing factors believed to be his perceived change of mind over plans to call a snap general election in October 2007, and his handling of the 10p tax rate cut in 2008, which led to allegations of weakness and dithering. His unpopularity led eight labour MPs to call for a leadership contest in September 2008, less than 15 months into his premiership. The threat of a leadership contest receded due to his perceived strong handling of the global financial crisis in October, but his popularity hit an all-time low, and his position became increasingly under threat after the May 2009 expenses scandal and Labour's poor results in the 2009 Local and European elections. Brown's cabinet began to rebel with several key resignations in the run up to local elections in June 2009.

In January 2010, it was revealed that Britain's economy had resumed growth after a recession which had seen a record six successive quarters of economic detraction. However, it was a narrow return to growth, and it came after the other major economies had come out of recession.[50]

The 2010 general election resulted in a hung parliament – Britain's first for 36 years – with the Conservative Party controlling 306 Seats, the Labour Party 258 Seats and the Liberal Democrats 57 Seats. Brown remained as prime minister while the Liberal Democrats negotiated with Labour and the Conservatives to form a coalition government. He announced his intention to resign on 10 May 2010 in order to help broker a Labour-Liberal Democrat deal. However, this became increasingly unlikely, and on 11 May Brown announced his resignation as Prime Minister and as Leader of the Labour Party. This paved the way for the Conservatives to return to power after 13 years.[51]

His deputy Harriet Harman became Leader of the Opposition until September 2010, when Ed Miliband was elected Leader of the Labour Party.

Conservative Government, 2010–present

David Cameron (2010–16)

Coalition government: 2010–15

The Conservative Party won the 2010 general election but did not win enough seats to win an outright majority. David Cameron, who has led the party since 2005 became Prime Minister on 11 May 2010 after the Conservatives formed a coalition government with the Liberal Democrats. Nick Clegg, leader of the Liberal Democrats was appointed Deputy Prime Minister and several other Liberal Democrats were given cabinet positions. Cameron promised to reduce Britain's spiralling budget deficit by cutting back on public service spending and by transferring more power to local authorities. He committed his government to Britain's continuing role in Afghanistan and stated that he hopes to remove British troops from the region by 2015. An emergency budget was prepared in June 2010 by Chancellor of the Exchequer George Osborne which stated that VAT will be raised to 20% and there will be a large reduction in public spending. A key Liberal Democrat policy is that of voting reform, to which a referendum took place in May 2011 on whether or not Britain should adopt a system of Alternative Vote to elect MPs to Westminster. However, the proposal was rejected overwhelmingly, with 68% of voters in favour of retaining first-past-the-post. The Liberal Democrat turnabout on tuition policy at the universities alienated their younger supporters, and the continuing weakness of the economy, despite spending cutbacks, alienated the elders.

In March 2011, UK, along with France and USA voted for military intervention against Gaddafi's Libya leading to 2011 military intervention in Libya. Prince William married Kate Middleton on 29 April 2011 in a globally televised event much like his parents' wedding 30 years earlier. In July 2013, the royal couple welcomed their first child, Prince George. In May 2015, they welcomed their second child, Charlotte Elizabeth Diana. On 6 August, the Death of Mark Duggan sparked off the 2011 England riots.

In 2012, the Summer Olympics returned to London for the first time since 1948. The United States claimed the largest count of gold medals, with Britain running third place after China.

Scottish independence referendum: 2014

On 18 September, Scotland voted in a referendum on the question of becoming an independent country. The No side, supported by the three major UK parties, secured a 55% to 45% majority for Scotland to remain part of the United Kingdom. Following the result, Scotland's First Minister, Alex Salmond, announced his intention to step down as First Minister and leader of the SNP. He was replaced by his deputy, Nicola Sturgeon.

Majority government: 2015–16

After years of austerity, the British economy was on an upswing in 2015. In line with the Fixed Term Parliaments Act, the 2015 general election was called for 7 May 2015. The Conservatives claimed credit for the upswing, promising to keep taxes low and reduce the deficit aa well as promising am In/Out referendum on the UK's relationship with the European Union. The rival Labour party called for a higher minimum wage, and higher taxes on the rich. In Scotland, the SNP attacked the austerity programme, opposed nuclear weapons and demanded that promises of more autonomy for Scotland made during the independence referendum be delivered.

Pre-election polls had predicted a close race and a hung parliament, but the surprising result was that a majority Conservative government was elected. The Conservatives with 37% of the popular vote held a narrow majority with 331 of the 650 seats. The other main victor was the Scottish National Party which won 56 of the 59 seats in Scotland, a gain of 50. Labour suffered its worst defeat since 1987, taking only 31% of the votes and 232 seats; they lost 40 of their 41 seats in Scotland. The Liberal Democrats vote plunged by 2/3 and they lost 49 of their 57 seats, as their coalition with the Conservatives had alienated the great majority of their supporters. The new UK Independence Party (UKIP), rallying voters against Europe and against immigration, did well with 13% of the vote count. It came in second in over 115 races but came in first in only one. Women now comprise 29% of the MPs.[52][53] Following the election, the Leaders of the Labour Party and Liberal Democrats both resigned. They were replaced by Jeremy Corbyn and Tim Farron, respectively.

Brexit: 2016

On 23 June 2016, UK voters elected to withdraw from the European Union by a thin margin (48% in favour of remaining, 52% in favour of leaving the European Union). London, Scotland, and Northern Ireland were three regions most in favour of the "Remain" vote, while Wales and England's northern region were strongly pro-"Leave". Although he called for the referendum, British Prime Minister David Cameron had campaigned ardently for the "Remain" vote. He faced significant opposition from other parties on the right who came to view British membership in the EU as a detriment to the country's security and economic vitality. United Kingdom Independence Party leader Nigel Farage called the vote Britain's "independence day".[54]

Brexit had a few immediate consequences. Hours after the results of the referendum, David Cameron announced that he would resign as Prime Minister, claiming that "fresh leadership" was needed.[55] In addition, because Scottish voters were highly in favour of remaining in the EU, Scotland's First Minister Nicola Sturgeon announced that the Scottish government would begin to organize another referendum on the question of Scottish independence.[56] On the economic side of things, the value of the British pound declined sharply after the results of the election were made clear. Stock markets in both Britain and New York were down the day after the referendum. Oil prices also fell.[57]

As part of the 2016 British political crisis, on July 4, 2016, Nigel Farage announced his resignation as head of UKIP.[58]

Theresa May (2016–)

A Conservative Party leadership election occurred following Cameron's announcement of his resignation. All candidates except Theresa May had either been eliminated or withdrawn from the race by 11 July 2016; a result, May automatically became the new Leader of the Conservative Party, to become Prime Minister on 13 July.

See also

Footnotes

- ↑ Bognador, Vernon. "Britain in the 20th Century: The Character of the Post-war Period". Gresham University. Retrieved 28 May 2013.

- ↑ Murphy, Mary (May 1952). "Nationalisation of British Industry". The Canadian Journal of Economics and Political Science. 2. 18. JSTOR 138140.

- 1 2 Darwin, John. "Britain, the Commonwealth and the End of Empire". BBC. Retrieved 28 May 2013.

- ↑ "Sir Edward Heath". Enclyclopædia Britannica. Retrieved 28 May 2013.

- ↑ Young, Hugo. "Margaret Thatcher (prime minister of United Kingdom)". Enclyclopædia Britannica. Retrieved 28 May 2013.

- ↑ "Margaret Thatcher: The lady who changed the world". The Economist. 8 April 2013. Retrieved 28 May 2013.

- ↑ Gallagher, Tom. "Tony Blair (prime minister of United Kingdom)". Enclylopædia Britannica.

- ↑ Butler 1989, p. 5.

- ↑ Brown, Jak. "History of Clement Attlee". Government of the United Kingdom. Retrieved 28 May 2013.

- ↑ Stephens (1997) p.xiv

- ↑ Butler (1989) p.9

- ↑ Butler (1989) p.11

- ↑ Bogdanor, Vernon (1 July 2005). "Harold Macmillan | Obituary". London: The Guardian. Retrieved 28 May 2013.

- ↑ Garry Keenor. "The Reshaping of British Railways – Part 1: Report". The Railways Archive. Retrieved 25 July 2010.

- ↑ E. Bruce Geelhoed, Anthony O. Edmonds (2003): Eisenhower, Macmillan and Allied Unity, 1957-1961. Palgrave Macmillan, ISBN 978-0-333-64227-6. (Review

- ↑ http://www.nationalarchives.gov.uk: Cabinet Papers - Strained consensus and Labour

- ↑ Beeching, Richard (1965). "The Development Of The Major Railway Trunk Routes" (PDF). HMSO.

- ↑ Philip Ziegler, Wilson: The Authorised Life (1993).