Hubble's law

| Part of a series on | |||

| Physical cosmology | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| |||

|

Early universe

|

|||

|

Components · Structure |

|||

| |||

Hubble's law is the name for the observation in physical cosmology that:

- Objects observed in deep space (extragalactic space, 10 megaparsecs (Mpc) or more) are found to have a Doppler shift interpretable as relative velocity away from Earth;

- This Doppler-shift-measured velocity, of various galaxies receding from the Earth, is approximately proportional to their distance from the Earth for galaxies up to a few hundred megaparsecs away.[1][2]

Hubble's law is considered the first observational basis for the expansion of the universe and today serves as one of the pieces of evidence most often cited in support of the Big Bang model.[3] The motion of astronomical objects due solely to this expansion is known as the Hubble flow.[4]

Although widely attributed to Edwin Hubble, the law was first derived from the general relativity equations by Georges Lemaître in a 1927 article where he proposed the expansion of the universe and suggested an estimated value of the rate of expansion, now called the Hubble constant.[5][6][7] Two years later Edwin Hubble confirmed the existence of that law and determined a more accurate value for the constant that now bears his name.[8] Hubble inferred the recession velocity of the objects from their redshifts, many of which were earlier measured and related to velocity by Vesto Slipher in 1917.[9][10][11][12]

The law is often expressed by the equation v = H0D, with H0 the constant of proportionality (Hubble constant) between the "proper distance" D to a galaxy (which can change over time, unlike the comoving distance) and its velocity v (i.e. the derivative of proper distance with respect to cosmological time coordinate; see Uses of the proper distance for some discussion of the subtleties of this definition of 'velocity'). The SI unit of H0 is s−1 but it is most frequently quoted in (km/s)/Mpc, thus giving the speed in km/s of a galaxy 1 megaparsec (3.09×1019 km) away. The reciprocal of H0 is the Hubble time.

Observed values

| Date published | Hubble constant (km/s)/Mpc |

Observer | Citation | Remarks / methodology |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2016-07-13 | 67.6+0.7 −0.6 |

SDSS-III Baryon Oscillation Spectroscopic Survey | [13] | |

| 2016-05-17 | 73.00±1.75 | Hubble Space Telescope | [14] | |

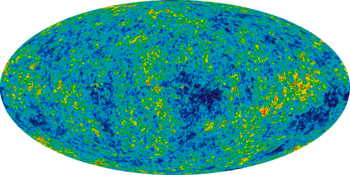

| 2013-03-21 | 67.80±0.77 | Planck Mission | [15][16][17][18][19] | The ESA Planck Surveyor was launched in May 2009. Over a four-year period, it performed a significantly more detailed investigation of cosmic microwave radiation than earlier investigations using HEMT radiometers and bolometer technology to measure the CMB at a smaller scale than WMAP. On 21 March 2013, the European-led research team behind the Planck cosmology probe released the mission's data including a new CMB all-sky map and their determination of the Hubble constant. |

| 2012-12-20 | 69.32±0.80 | WMAP (9-years) | [20] | |

| 2010 | 70.4+1.3 −1.4 |

WMAP (7-years), combined with other measurements. | [21] | These values arise from fitting a combination of WMAP and other cosmological data to the simplest version of the ΛCDM model. If the data are fit with more general versions, H0 tends to be smaller and more uncertain: typically around 67±4 (km/s)/Mpc although some models allow values near 63 (km/s)/Mpc.[22] |

| 2010 | 71.0±2.5 | WMAP only (7-years). | [21] | |

| 2009-02 | 70.1±1.3 | WMAP (5-years). combined with other measurements. | [23] | |

| 2009-02 | 71.9+2.6 −2.7 |

WMAP only (5-years) | [23] | |

| 2007 | 70.4+1.5 −1.6 |

WMAP (3-years) | [24] | |

| 2006-08 | 77.6+14.9 −12.5 |

Chandra X-ray Observatory | [25] | |

| 2001-05 | 72±8 | Hubble Space Telescope | [26] | This project established the most precise optical determination, consistent with a measurement of H0 based upon Sunyaev-Zel'dovich effect observations of many galaxy clusters having a similar accuracy. |

| prior to 1996 | 50–90 (est.) | [27] | ||

| 1958 | 75 (est.) | Allan Sandage | [28] | This was the first good estimate of H0, but it would be decades before a consensus was achieved. |

Discovery

A decade before Hubble made his observations, a number of physicists and mathematicians had established a consistent theory of the relationship between space and time by using Einstein's field equations of general relativity. Applying the most general principles to the nature of the universe yielded a dynamic solution that conflicted with the then-prevailing notion of a static universe.

FLRW equations

In 1922, Alexander Friedmann derived his Friedmann equations from Einstein's field equations, showing that the Universe might expand at a rate calculable by the equations.[29] The parameter used by Friedmann is known today as the scale factor which can be considered as a scale invariant form of the proportionality constant of Hubble's law. Georges Lemaître independently found a similar solution in 1927. The Friedmann equations are derived by inserting the metric for a homogeneous and isotropic universe into Einstein's field equations for a fluid with a given density and pressure. This idea of an expanding spacetime would eventually lead to the Big Bang and Steady State theories of cosmology.

Lemaitre's Equation

In 1927, two years before Hubble published his own article, the Belgian priest and astronomer Georges Lemaître was the first to publish research deriving what is now known as Hubble's Law. According to the Canadian astronomer Sidney van den Bergh, "The 1927 discovery of the expansion of the Universe by Lemaitre was published in French in a low-impact journal. In the 1931 high-impact English translation of this article a critical equation was changed by omitting reference to what is now known as the Hubble constant.".[30] It is now known that the alterations in the translated paper were carried out by Lemaitre himself.[6][31]

Shape of the universe

Before the advent of modern cosmology, there was considerable talk about the size and shape of the universe. In 1920, the famous Shapley-Curtis debate took place between Harlow Shapley and Heber D. Curtis over this issue. Shapley argued for a small universe the size of the Milky Way galaxy and Curtis argued that the Universe was much larger. The issue was resolved in the coming decade with Hubble's improved observations.

Cepheid variable stars outside of the Milky Way

Edwin Hubble did most of his professional astronomical observing work at Mount Wilson Observatory, home to the world's most powerful telescope at the time. His observations of Cepheid variable stars in spiral nebulae enabled him to calculate the distances to these objects. Surprisingly, these objects were discovered to be at distances which placed them well outside the Milky Way. They continued to be called "nebulae" and it was only gradually that the term "galaxies" took over.

Combining redshifts with distance measurements

The parameters that appear in Hubble’s law: velocities and distances, are not directly measured. In reality we determine, say, a supernova brightness, which provides information about its distance, and the redshift z = ∆λ/λ of its spectrum of radiation. Hubble correlated brightness and parameter z.

Combining his measurements of galaxy distances with Vesto Slipher and Milton Humason's measurements of the redshifts associated with the galaxies, Hubble discovered a rough proportionality between redshift of an object and its distance. Though there was considerable scatter (now known to be caused by peculiar velocities – the 'Hubble flow' is used to refer to the region of space far enough out that the recession velocity is larger than local peculiar velocities), Hubble was able to plot a trend line from the 46 galaxies he studied and obtain a value for the Hubble constant of 500 km/s/Mpc (much higher than the currently accepted value due to errors in his distance calibrations). (See cosmic distance ladder for details.)

At the time of discovery and development of Hubble's law, it was acceptable to explain redshift phenomenon as a Doppler shift in the context of special relativity, and use the Doppler formula to associate redshift z with velocity. Today, the velocity-distance relationship of Hubble's law is viewed as a theoretical result with velocity to be connected with observed redshift not by the Doppler effect, but by a cosmological model relating recessional velocity to the expansion of the Universe. Even for small z the velocity entering the Hubble law is no longer interpreted as a Doppler effect, although at small z the velocity-redshift relation for both interpretations is the same.

Hubble Diagram

Hubble's law can be easily depicted in a "Hubble Diagram" in which the velocity (assumed approximately proportional to the redshift) of an object is plotted with respect to its distance from the observer.[34] A straight line of positive slope on this diagram is the visual depiction of Hubble's law.

Cosmological constant abandoned

After Hubble's discovery was published, Albert Einstein abandoned his work on the cosmological constant, which he had designed to modify his equations of general relativity, to allow them to produce a static solution which, in their simplest form, model either an expanding or contracting universe.[35] After Hubble's discovery that the Universe was, in fact, expanding, Einstein called his faulty assumption that the Universe is static his "biggest mistake".[35] On its own, general relativity could predict the expansion of the Universe, which (through observations such as the bending of light by large masses, or the precession of the orbit of Mercury) could be experimentally observed and compared to his theoretical calculations using particular solutions of the equations he had originally formulated.

In 1931, Einstein made a trip to Mount Wilson to thank Hubble for providing the observational basis for modern cosmology.[36]

The cosmological constant has regained attention in recent decades as a hypothesis for dark energy.[37]

Interpretation

The discovery of the linear relationship between redshift and distance, coupled with a supposed linear relation between recessional velocity and redshift, yields a straightforward mathematical expression for Hubble's Law as follows:

where

- is the recessional velocity, typically expressed in km/s.

- H0 is Hubble's constant and corresponds to the value of (often termed the Hubble parameter which is a value that is time dependent and which can be expressed in terms of the scale factor) in the Friedmann equations taken at the time of observation denoted by the subscript 0. This value is the same throughout the Universe for a given comoving time.

- is the proper distance (which can change over time, unlike the comoving distance, which is constant) from the galaxy to the observer, measured in mega parsecs (Mpc), in the 3-space defined by given cosmological time. (Recession velocity is just v = dD/dt).

Hubble's law is considered a fundamental relation between recessional velocity and distance. However, the relation between recessional velocity and redshift depends on the cosmological model adopted, and is not established except for small redshifts.

For distances D larger than the radius of the Hubble sphere rHS , objects recede at a rate faster than the speed of light (See Uses of the proper distance for a discussion of the significance of this):

Since the Hubble "constant" is a constant only in space, not in time, the radius of the Hubble sphere may increase or decrease over various time intervals. The subscript '0' indicates the value of the Hubble constant today.[32] Current evidence suggests that the expansion of the Universe is accelerating (see Accelerating universe), meaning that, for any given galaxy, the recession velocity dD/dt is increasing over time as the galaxy moves to greater and greater distances; however, the Hubble parameter is actually thought to be decreasing with time, meaning that if we were to look at some fixed distance D and watch a series of different galaxies pass that distance, later galaxies would pass that distance at a smaller velocity than earlier ones.[39]

Redshift velocity and recessional velocity

Redshift can be measured by determining the wavelength of a known transition, such as hydrogen α-lines for distant quasars, and finding the fractional shift compared to a stationary reference. Thus redshift is a quantity unambiguous for experimental observation. The relation of redshift to recessional velocity is another matter. For an extensive discussion, see Harrison.[40]

Redshift velocity

The redshift z is often described as a redshift velocity, which is the recessional velocity that would produce the same redshift if it were caused by a linear Doppler effect (which, however, is not the case, as the shift is caused in part by a cosmological expansion of space, and because the velocities involved are too large to use a non-relativistic formula for Doppler shift). This redshift velocity can easily exceed the speed of light.[41] In other words, to determine the redshift velocity vrs, the relation:

is used.[42][43] That is, there is no fundamental difference between redshift velocity and redshift: they are rigidly proportional, and not related by any theoretical reasoning. The motivation behind the "redshift velocity" terminology is that the redshift velocity agrees with the velocity from a low-velocity simplification of the so-called Fizeau-Doppler formula[44]

Here, λo, λe are the observed and emitted wavelengths respectively. The "redshift velocity" vrs is not so simply related to real velocity at larger velocities, however, and this terminology leads to confusion if interpreted as a real velocity. Next, the connection between redshift or redshift velocity and recessional velocity is discussed. This discussion is based on Sartori.[45]

Recessional velocity

Suppose R(t) is called the scale factor of the Universe, and increases as the Universe expands in a manner that depends upon the cosmological model selected. Its meaning is that all measured proper distances D(t) between co-moving points increase proportionally to R. (The co-moving points are not moving relative to each other except as a result of the expansion of space.) In other words:

where t0 is some reference time. If light is emitted from a galaxy at time te and received by us at t0, it is red shifted due to the expansion of space, and this redshift z is simply:

Suppose a galaxy is at distance D, and this distance changes with time at a rate dtD . We call this rate of recession the "recession velocity" vr:

We now define the Hubble constant as

and discover the Hubble law:

From this perspective, Hubble's law is a fundamental relation between (i) the recessional velocity contributed by the expansion of space and (ii) the distance to an object; the connection between redshift and distance is a crutch used to connect Hubble's law with observations. This law can be related to redshift z approximately by making a Taylor series expansion:

If the distance is not too large, all other complications of the model become small corrections and the time interval is simply the distance divided by the speed of light:

- or

According to this approach, the relation cz = vr is an approximation valid at low redshifts, to be replaced by a relation at large redshifts that is model-dependent. See velocity-redshift figure.

Observability of parameters

Strictly speaking, neither v nor D in the formula are directly observable, because they are properties now of a galaxy, whereas our observations refer to the galaxy in the past, at the time that the light we currently see left it.

For relatively nearby galaxies (redshift z much less than unity), v and D will not have changed much, and v can be estimated using the formula where c is the speed of light. This gives the empirical relation found by Hubble.

For distant galaxies, v (or D) cannot be calculated from z without specifying a detailed model for how H changes with time. The redshift is not even directly related to the recession velocity at the time the light set out, but it does have a simple interpretation: (1+z) is the factor by which the Universe has expanded while the photon was travelling towards the observer.

Expansion velocity vs relative velocity

In using Hubble's law to determine distances, only the velocity due to the expansion of the Universe can be used. Since gravitationally interacting galaxies move relative to each other independent of the expansion of the Universe, these relative velocities, called peculiar velocities, need to be accounted for in the application of Hubble's law.

The Finger of God effect is one result of this phenomenon. In systems that are gravitationally bound, such as galaxies or our planetary system, the expansion of space is a much weaker effect than the attractive force of gravity.

Idealized Hubble's Law

The mathematical derivation of an idealized Hubble's Law for a uniformly expanding universe is a fairly elementary theorem of geometry in 3-dimensional Cartesian/Newtonian coordinate space, which, considered as a metric space, is entirely homogeneous and isotropic (properties do not vary with location or direction). Simply stated the theorem is this:

- Any two points which are moving away from the origin, each along straight lines and with speed proportional to distance from the origin, will be moving away from each other with a speed proportional to their distance apart.

In fact this applies to non-Cartesian spaces as long as they are locally homogeneous and isotropic; specifically to the negatively and positively curved spaces frequently considered as cosmological models (see shape of the universe).

An observation stemming from this theorem is that seeing objects recede from us on Earth is not an indication that Earth is near to a center from which the expansion is occurring, but rather that every observer in an expanding universe will see objects receding from them.

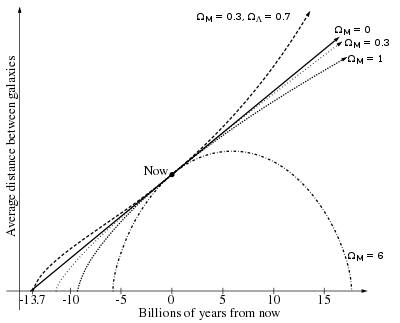

Ultimate fate and age of the universe

The value of the Hubble parameter changes over time, either increasing or decreasing depending on the value of the so-called deceleration parameter , which is defined by

In a universe with a deceleration parameter equal to zero, it follows that H = 1/t, where t is the time since the Big Bang. A non-zero, time-dependent value of simply requires integration of the Friedmann equations backwards from the present time to the time when the comoving horizon size was zero.

It was long thought that q was positive, indicating that the expansion is slowing down due to gravitational attraction. This would imply an age of the Universe less than 1/H (which is about 14 billion years). For instance, a value for q of 1/2 (once favoured by most theorists) would give the age of the Universe as 2/(3H). The discovery in 1998 that q is apparently negative means that the Universe could actually be older than 1/H. However, estimates of the age of the universe are very close to 1/H.

Olbers' paradox

The expansion of space summarized by the Big Bang interpretation of Hubble's Law is relevant to the old conundrum known as Olbers' paradox: if the Universe were infinite, static, and filled with a uniform distribution of stars, then every line of sight in the sky would end on a star, and the sky would be as bright as the surface of a star. However, the night sky is largely dark. Since the 17th century, astronomers and other thinkers have proposed many possible ways to resolve this paradox, but the currently accepted resolution depends in part on the Big Bang theory and in part on the Hubble expansion. In a universe that exists for a finite amount of time, only the light of a finite number of stars has had a chance to reach us yet, and the paradox is resolved. Additionally, in an expanding universe, distant objects recede from us, which causes the light emanating from them to be redshifted and diminished in brightness.[47]

Dimensionless Hubble parameter

Instead of working with Hubble's constant, a common practice is to introduce the dimensionless Hubble parameter, usually denoted by h, and to write the Hubble's parameter H0 as h × 100 km s−1 Mpc−1, all the uncertainty relative of the value of H0 being then relegated to h.[48] If a subscript is presented after h, it refers to the value of h used in that text's preceding calculation, and is equal to H0 / 100. Currently h = 0.678, which can be represented as h0.678. This should not be confused with the dimensionless value of Hubble's constant, usually expressed in terms of Planck units, with current value of H0×tP = 1.18 × 10−61.

Determining the Hubble constant

The value of the Hubble constant is estimated by measuring the redshift of distant galaxies and then determining the distances to the same galaxies (by some other method than Hubble's law). Uncertainties in the physical assumptions used to determine these distances have caused varying estimates of the Hubble constant.

Earlier measurement and discussion approaches

For most of the second half of the 20th century the value of was estimated to be between 50 and 90 (km/s)/Mpc.

The value of the Hubble constant was the topic of a long and rather bitter controversy between Gérard de Vaucouleurs, who claimed the value was around 100, and Allan Sandage, who claimed the value was near 50.[27] In 1996, a debate moderated by John Bahcall between Sidney van den Bergh and Gustav Tammann was held in similar fashion to the earlier Shapley-Curtis debate over these two competing values.

This previously wide variance in estimates was partially resolved with the introduction of the ΛCDM model of the Universe in the late 1990s. With the ΛCDM model observations of high-redshift clusters at X-ray and microwave wavelengths using the Sunyaev-Zel'dovich effect, measurements of anisotropies in the cosmic microwave background radiation, and optical surveys all gave a value of around 70 for the constant.

More recent measurements from the Planck mission indicate a lower value of around 67.[15]

See table of measurements above for many recent and older measurements.

Acceleration of the expansion

A value for measured from standard candle observations of Type Ia supernovae, which was determined in 1998 to be negative, surprised many astronomers with the implication that the expansion of the Universe is currently "accelerating"[49] (although the Hubble factor is still decreasing with time, as mentioned above in the Interpretation section; see the articles on dark energy and the ΛCDM model).

Derivation of the Hubble parameter

Start with the Friedmann equation:

where is the Hubble parameter, is the scale factor, G is the gravitational constant, is the normalised spatial curvature of the Universe and equal to −1, 0, or +1, and is the cosmological constant.

Matter-dominated universe (with a cosmological constant)

If the Universe is matter-dominated, then the mass density of the Universe can just be taken to include matter so

where is the density of matter today. We know for nonrelativistic particles that their mass density decreases proportional to the inverse volume of the Universe, so the equation above must be true. We can also define (see density parameter for )

so Also, by definition,

and

where the subscript nought refers to the values today, and . Substituting all of this into the Friedmann equation at the start of this section and replacing with gives

Matter- and dark energy-dominated universe

If the Universe is both matter-dominated and dark energy- dominated, then the above equation for the Hubble parameter will also be a function of the equation of state of dark energy. So now:

where is the mass density of the dark energy. By definition, an equation of state in cosmology is , and if this is substituted into the fluid equation, which describes how the mass density of the Universe evolves with time, then

If w is constant, then

Therefore, for dark energy with a constant equation of state w, . If this is substituted into the Friedman equation in a similar way as before, but this time set , which assumes a spatially flat universe, then (see Shape of the Universe)

If the dark energy derives from a cosmological constant such as that introduced by Einstein, it can be shown that . The equation then reduces to the last equation in the matter-dominated universe section, with set to zero. In that case the initial dark energy density is given by[50]

- and

If dark energy does not have a constant equation-of-state w, then

and to solve this, must be parametrized, for example if , giving

Other ingredients have been formulated recently.[51][52][53]

Units derived from the Hubble constant

Hubble time

The Hubble constant has units of inverse time; the Hubble time tH is simply defined as the inverse of the Hubble constant,[54] i.e. = 14.4 billion years. This is slightly different from the age of the universe 13.8 billion years. The Hubble time is the age it would have had if the expansion had been linear, and it is different from the real age of the universe because the expansion isn't linear; they are related by a dimensionless factor which depends on the mass-energy content of the universe, which is around 0.96 in the standard Lambda-CDM model.

We currently appear to be approaching a period where the expansion is exponential due to the increasing dominance of vacuum energy. In this regime, the Hubble parameter is constant, and the universe grows by a factor e each Hubble time:

Over long periods of time, the dynamics are complicated by general relativity, dark energy, inflation, etc., as explained above.

Hubble length

The Hubble length or Hubble distance is a unit of distance in cosmology, defined as cH0−1 — the speed of light multiplied by the Hubble time. It is equivalent to 4,550 million parsecs or 14.4 billion light years. (The numerical value of the Hubble length in light years is, by definition, equal to that of the Hubble time in years.) The Hubble distance would be the distance between the Earth and the galaxies which are currently receding from us at the speed of light, as can be seen by substituting D = c/H0 into the equation for Hubble's law, v = H0D.

Hubble volume

The Hubble volume is sometimes defined as a volume of the Universe with a comoving size of c/H0. The exact definition varies: it is sometimes defined as the volume of a sphere with radius c/H0, or alternatively, a cube of side c/H0. Some cosmologists even use the term Hubble volume to refer to the volume of the observable universe, although this has a radius approximately three times larger.

See also

Notes

- ↑ Riess, A.; et al. (September 1998). "Observational Evidence from Supernovae for an Accelerating Universe and a Cosmological Constant". The Astronomical Journal. 116 (3): 1009–1038. arXiv:astro-ph/9805201

. Bibcode:1998AJ....116.1009R. doi:10.1086/300499.

. Bibcode:1998AJ....116.1009R. doi:10.1086/300499. - ↑ Perlmutter, S.; et al. (June 1999). "Measurements of Omega and Lambda from 42 High-Redshift Supernovae". The Astrophysical Journal. 517 (2): 565–586. arXiv:astro-ph/9812133

. Bibcode:1999ApJ...517..565P. doi:10.1086/307221.

. Bibcode:1999ApJ...517..565P. doi:10.1086/307221. - ↑ Coles, P., ed. (2001). Routledge Critical Dictionary of the New Cosmology. Routledge. p. 202. ISBN 0-203-16457-1.

- ↑ "Hubble Flow". The Swinburne Astronomy Online Encyclopedia of Astronomy. Swinburne University of Technology. Retrieved 2013-05-14.

- ↑ Lemaître, G. (1927). "Un univers homogène de masse constante et de rayon croissant rendant compte de la vitesse radiale des nébuleuses extra-galactiques". Annales de la Société Scientifique de Bruxelles A (47): 49–59. Bibcode:1927ASSB...47...49L. Partially translated in Lemaître, G. (1931). "Expansion of the universe, A homogeneous universe of constant mass and increasing radius accounting for the radial velocity of extra-galactic nebulae". Monthly Notices of the Royal Astronomical Society. 91: 483–490. Bibcode:1931MNRAS..91..483L. doi:10.1093/mnras/91.5.483.

- 1 2 Livio, M. (2011). "Lost in translation: Mystery of the missing text solved". Nature. 479 (7372): 171. Bibcode:2011Natur.479..171L. doi:10.1038/479171a.

- ↑ Livio, M.; Riess, A. (2013). "Measuring the Hubble constant". Physics Today. 66 (10): 41. Bibcode:2013PhT....66j..41L. doi:10.1063/PT.3.2148.

- ↑ Hubble, E. (1929). "A relation between distance and radial velocity among extra-galactic nebulae". Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences. 15 (3): 168–73. Bibcode:1929PNAS...15..168H. doi:10.1073/pnas.15.3.168. PMC 522427

. PMID 16577160.

. PMID 16577160. - ↑ Slipher, V.M. (1917). "Radial velocity observations of spiral nebulae". The Observatory. 40: 304–306.

- ↑ Longair, M. S. (2006). The Cosmic Century. Cambridge University Press. p. 109. ISBN 0-521-47436-1.

- ↑ Nussbaumer, Harry (2013). 'Slipher's redshifts as support for de Sitter's model and the discovery of the dynamic universe' In Origins of the Expanding Universe: 1912-1932. Astronomical Society of the Pacific. pp. 25–38.Physics ArXiv preprint

- ↑ O'Raifeartaigh, Cormac (2013). The Contribution of V.M. Slipher to the discovery of the expanding universe in 'Origins of the Expanding Universe'. Astronomical Society of the Pacific. pp. 49–62.Physics ArXiv preprint

- ↑ Grieb, Jan N.; Sánchez, Ariel G.; Salazar-Albornoz, Salvador (2016-07-13). "The clustering of galaxies in the completed SDSS-III Baryon Oscillation Spectroscopic Survey: Cosmological implications of the Fourier space wedges of the nal sample". arXiv:1607.03143

.

. - ↑ Riess, Adam G.; Macri, Lucas M.; Hoffmann, Samantha L.; Scolnic, Dan; Casertano, Stefano; Filippenko, Alexei V.; Tucker, Brad E.; Reid, Mark J.; Jones, David O. (2016-04-05). "A 2.4% Determination of the Local Value of the Hubble Constant". arXiv:1604.01424

.

. - 1 2 3 Bucher, P. A. R.; et al. (Planck Collaboration) (2013). "Planck 2013 results. I. Overview of products and scientific Results". arXiv:1303.5062

[astro-ph.CO].

[astro-ph.CO]. - ↑ "Planck reveals an almost perfect universe". ESA. 21 March 2013. Retrieved 2013-03-21.

- ↑ "Planck Mission Brings Universe Into Sharp Focus". JPL. 21 March 2013. Retrieved 2013-03-21.

- ↑ Overbye, D. (21 March 2013). "An infant universe, born before we knew". New York Times. Retrieved 2013-03-21.

- ↑ Boyle, A. (21 March 2013). "Planck probe's cosmic 'baby picture' revises universe's vital statistics". NBC News. Retrieved 2013-03-21.

- ↑ Bennett, C. L.; et al. (2013). "Nine-year Wilkinson Microwave Anisotropy Probe (WMAP) observations: Final maps and results". The Astrophysical Journal Supplement Series. 208 (2): 20. arXiv:1212.5225

. Bibcode:2013ApJS..208...20B. doi:10.1088/0067-0049/208/2/20.

. Bibcode:2013ApJS..208...20B. doi:10.1088/0067-0049/208/2/20. - 1 2 Jarosik, N.; et al. (2011). "Seven-year Wilkinson Microwave Anisotropy Probe (WMAP) observations: Sky maps, systematic errors, and basic results". The Astrophysical Journal Supplement Series. 192 (2): 14. arXiv:1001.4744

. Bibcode:2011ApJS..192...14J. doi:10.1088/0067-0049/192/2/14.

. Bibcode:2011ApJS..192...14J. doi:10.1088/0067-0049/192/2/14. - ↑ Results for H0 and other cosmological parameters obtained by fitting a variety of models to several combinations of WMAP and other data are available at the NASA's LAMBDA website.

- 1 2 Hinshaw, G.; et al. (WMAP Collaboration) (2009). "Five-year Wilkinson Microwave Anisotropy Probe observations: Data processing, sky maps, and basic results". The Astrophysical Journal Supplement. 180 (2): 225–245. arXiv:0803.0732

. Bibcode:2009ApJS..180..225H. doi:10.1088/0067-0049/180/2/225.

. Bibcode:2009ApJS..180..225H. doi:10.1088/0067-0049/180/2/225. - ↑ Spergel, D. N.; et al. (WMAP Collaboration) (2007). "Three-year Wilkinson Microwave Anisotropy Probe (WMAP) Observations: Implications for cosmology". The Astrophysical Journal Supplement Series. 170 (2): 377–408. arXiv:astro-ph/0603449

. Bibcode:2007ApJS..170..377S. doi:10.1086/513700.

. Bibcode:2007ApJS..170..377S. doi:10.1086/513700. - ↑ Bonamente, M.; Joy, M. K.; Laroque, S. J.; Carlstrom, J. E.; Reese, E. D.; Dawson, K. S. (2006). "Determination of the cosmic distance scale from Sunyaev–Zel'dovich effect and Chandra X‐ray measurements of high‐redshift galaxy clusters". The Astrophysical Journal. 647: 25. arXiv:astro-ph/0512349

. Bibcode:2006ApJ...647...25B. doi:10.1086/505291.

. Bibcode:2006ApJ...647...25B. doi:10.1086/505291. - 1 2 Freedman, W. L.; et al. (2001). "Final results from the Hubble Space Telescope Key Project to measure the Hubble constant". The Astrophysical Journal. 553 (1): 47–72. arXiv:astro-ph/0012376

. Bibcode:2001ApJ...553...47F. doi:10.1086/320638.

. Bibcode:2001ApJ...553...47F. doi:10.1086/320638. - 1 2 Overbye, D. (1999). "Prologue". Lonely Hearts of the Cosmos (2nd ed.). HarperCollins. p. 1ff. ISBN 978-0-316-64896-7.

- ↑ Sandage, A. R. (1958). "Current problems in the extragalactic distance scale". The Astrophysical Journal. 127 (3): 513–526. Bibcode:1958ApJ...127..513S. doi:10.1086/146483.

- ↑ Friedman, A. (1922). "Über die Krümmung des Raumes". Zeitschrift für Physik. 10 (1): 377–386. Bibcode:1922ZPhy...10..377F. doi:10.1007/BF01332580. Translated in Friedmann, A. (1999). "On the Curvature of Space". General Relativity and Gravitation. 31 (12): 1991–2000. Bibcode:1999GReGr..31.1991F. doi:10.1023/A:1026751225741.

- ↑ van den Bergh, Sydney. "The Curious Case of Lemaitre's Equation No. 24". arXiv:1106.1195

.

. - ↑ Block, David (2012). 'Georges Lemaitre and Stigler's law of eponymy' in Georges Lemaitre: Life, Science and Legacy (Holder and Mitton ed.). Springer. pp. 89–96.

- 1 2 Keel, W. C. (2007). The Road to Galaxy Formation (2nd ed.). Springer. pp. 7–8. ISBN 3-540-72534-2.

- ↑ Weinberg, S. (2008). Cosmology. Oxford University Press. p. 28. ISBN 0-19-852682-2.

- ↑ Kirshner, R. P. (2003). "Hubble's diagram and cosmic expansion". Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences. 101 (1): 8–13. Bibcode:2003PNAS..101....8K. doi:10.1073/pnas.2536799100.

- 1 2 "What is a Cosmological Constant?". Goddard Space Flight Center. Retrieved 2013-10-17.

- ↑ Isaacson, W. (2007). Einstein: His Life and Universe. Simon & Schuster. p. 354. ISBN 0-7432-6473-8.

- ↑ "Einstein's Biggest Blunder? Dark Energy May Be Consistent With Cosmological Constant". Science Daily. 28 November 2007. Retrieved 2013-06-02.

- ↑ Davis, T. M.; Lineweaver, C. H. (2001). "Superluminal Recessional Velocities". AIP Conference Proceedings. 555: 348–351. arXiv:astro-ph/0011070

. Bibcode:2001AIPC..555..348D. doi:10.1063/1.1363540.

. Bibcode:2001AIPC..555..348D. doi:10.1063/1.1363540. - ↑ "Is the universe expanding faster than the speed of light?". Ask an Astronomer at Cornell University. Archived from the original on 23 November 2003. Retrieved 5 June 2015.

- ↑ Harrison, E. (1992). "The redshift-distance and velocity-distance laws". The Astrophysical Journal. 403: 28–31. Bibcode:1993ApJ...403...28H. doi:10.1086/172179.

- ↑ Madsen, M. S. (1995). The Dynamic Cosmos. CRC Press. p. 35. ISBN 0-412-62300-5.

- ↑ Dekel, A.; Ostriker, J. P. (1999). Formation of Structure in the Universe. Cambridge University Press. p. 164. ISBN 0-521-58632-1.

- ↑ Padmanabhan, T. (1993). Structure formation in the universe. Cambridge University Press. p. 58. ISBN 0-521-42486-0.

- ↑ Sartori, L. (1996). Understanding Relativity. University of California Press. p. 163, Appendix 5B. ISBN 0-520-20029-2.

- ↑ Sartori, L. (1996). Understanding Relativity. University of California Press. pp. 304–305. ISBN 0-520-20029-2.

- ↑ "Introduction to Cosmology", Matts Roos

- ↑ Chase, S. I.; Baez, J. C. (2004). "Olbers' Paradox". The Original Usenet Physics FAQ. Retrieved 2013-10-17. See also Asimov, I. (1974). "The Black of Night". Asimov on Astronomy. Doubleday. ISBN 0-385-04111-X.

- ↑ Peebles, P. J. E. (1993). Principles of Physical Cosmology. Princeton University Press.

- ↑ Perlmutter, S. (2003). "Supernovae, Dark Energy, and the Accelerating Universe" (PDF). Physics Today. 56 (4): 53–60. Bibcode:2003PhT....56d..53P. doi:10.1063/1.1580050.

- ↑ Carroll, Sean (2004). Spacetime and Geometry: An Introduction to General Relativity (illustrated ed.). San Fraancisco: Addison-Wesley. p. 328. ISBN 978-0-8053-8732-2.

- ↑ Tawfik, A.; Harko, T. (2012). "Quark-hadron phase transitions in the viscous early universe". Physical Review D. 85 (8): 084032. arXiv:1108.5697

. Bibcode:2012PhRvD..85h4032T. doi:10.1103/PhysRevD.85.084032.

. Bibcode:2012PhRvD..85h4032T. doi:10.1103/PhysRevD.85.084032. - ↑ Tawfik, A. (2011). "The Hubble parameter in the early universe with viscous QCD matter and finite cosmological constant". Annalen der Physik. 523 (5): 423. arXiv:1102.2626

. Bibcode:2011AnP...523..423T. doi:10.1002/andp.201100038.

. Bibcode:2011AnP...523..423T. doi:10.1002/andp.201100038. - ↑ Tawfik, A.; Wahba, M.; Mansour, H.; Harko, T. (2011). "Viscous quark-gluon plasma in the early universe". Annalen der Physik. 523 (3): 194. arXiv:1001.2814

. Bibcode:2011AnP...523..194T. doi:10.1002/andp.201000052.

. Bibcode:2011AnP...523..194T. doi:10.1002/andp.201000052. - ↑ Hawley, John F.; Holcomb, Katherine A. (2005). Foundations of modern cosmology (2nd ed.). Oxford [u.a.]: Oxford Univ. Press. p. 304. ISBN 0-19-853096-X.

References

- Hubble, E. P. (1937). The Observational Approach to Cosmology. Clarendon Press. LCCN 38011865.

- Kutner, M. (2003). Astronomy: A Physical Perspective. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 0-521-52927-1.

- Liddle, A. R. (2003). An Introduction to Modern Cosmology (2nd ed.). John Wiley & Sons. ISBN 0-470-84835-9.

Further reading

- Freedman, W. L.; Madore, B. F. (2010). "The Hubble Constant". Annual Review of Astronomy and Astrophysics. 48: 673. arXiv:1004.1856

. Bibcode:2010ARA&A..48..673F. doi:10.1146/annurev-astro-082708-101829.

. Bibcode:2010ARA&A..48..673F. doi:10.1146/annurev-astro-082708-101829.

External links

- NASA's WMAP - Big Bang Expansion: the Hubble Constant

- The Hubble Key Project

- The Hubble Diagram Project

- Merrifield, Michael (2009). "Hubble Constant". Sixty Symbols. Brady Haran for the University of Nottingham.