Hurricane Juan (1985)

| Category 1 hurricane (SSHWS/NWS) | |

Hurricane Juan near peak intensity | |

| Formed | October 26, 1985 |

|---|---|

| Dissipated | November 1, 1985 |

| Highest winds |

1-minute sustained: 85 mph (140 km/h) |

| Lowest pressure | 971 mbar (hPa); 28.67 inHg |

| Fatalities | 12 overall |

| Damage | $1.5 billion (1985 USD) |

| Areas affected | Gulf Coast of the United States (especially Louisiana), central United States |

| Part of the 1985 Atlantic hurricane season | |

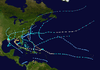

Hurricane Juan was a large and erratic tropical cyclone that looped twice near the Louisiana coast, causing widespread flooding. It was the tenth named storm of the 1985 Atlantic hurricane season, forming in the central Gulf of Mexico in late October. Juan moved northward after its formation, and was subtropical in nature with its large size. On October 27, the storm became a hurricane, reaching maximum sustained winds of 85 mph (140 km/h). Due to the influence of an upper-level low, Juan looped just off southern Louisiana before making landfall near Morgan City on October 29. Weakening to tropical storm status over land, Juan turned back to the southeast over open waters, crossing the Mississippi River Delta. After turning to the northeast, the storm made its final landfall just west of Pensacola, Florida, late on October 31. Juan continued quickly to the north and was absorbed by an approaching cold front, although its moisture contributed to a deadly flood event in the Mid-Atlantic states.

Juan was the last of three hurricanes to move over Louisiana during the season, after Danny in August and Elena in early September. It formed rapidly in the northern Gulf of Mexico, allowing little time for thorough preparations or the evacuation of offshore oil rigs. As a result, nine people died in maritime accidents off Louisiana. Onshore, the hurricane dropped torrential rain totaling 17.78 in (452 mm) in Galliano, Louisiana. The combination of the rainfall and a high storm surge flooded 50,000 houses and many communities in southern Louisiana, causing extensive agriculture losses. Damage in Louisiana alone approached $1 billion (1985 USD). Elsewhere, flooding in Texas forced the closure of roadways, while heavy rains damaged crops and houses in southern Mississippi. The outer rainbands of Juan spawned 15 tornadoes along the Florida Panhandle, causing over $1 million in damage. Overall, Juan directly inflicted about $1.5 billion in damage, making it among the costliest United States hurricanes, and there were 12 deaths. This excludes the effects from the subsequent flooding in the Mid-Atlantic.

Meteorological history

The interaction between a tropical wave and a upper-level low moving southeastward from Texas spawned a broad trough over the central Gulf of Mexico on October 24. That day, there was a marked increase in convection, or thunderstorms.[1] At the same time, the pressure gradient between the trough and a high pressure area over the southeastern United States produced winds of near gale force across the northern Gulf of Mexico.[2] Early on October 26, a tropical depression developed about 380 mi (610 km) south-southwest of New Orleans. Within 12 hours, the depression intensified into Tropical Storm Juan,[3] based on satellite imagery and reports from the Hurricane Hunters. Initially, the structure was akin to that of a subtropical cyclone, with light winds near the center. Juan moved erratically at first, eventually tracking more steadily to the north-northeast on October 27.[1] After turning to the northwest late on October 27, Juan intensified into a hurricane, with maximum sustained winds of 75 mph (120 km/h), based on reports from the Hurricane Hunters.[2]

Under the effects of a larger upper-level low, Juan slowed on October 28 while approaching the Louisiana coastline.[2] At 1200 UTC that day, the hurricane attained peak winds of 85 mph (140 km/h).[3] After executing a loop just offshore southern Louisiana, Juan turned back to the east, making landfall at peak intensity near Morgan City at 1100 UTC on October 29.[2][4] Subsequently, Juan turned sharply to the northwest, executing another loop over southern Louisiana near Lafayette. Late on October 29, the hurricane weakened to tropical storm status, emerging into Vermilion Bay early the next day with winds of 65 mph (100 km/h). Juan turned to the east, moving along the southern Louisiana coast and re-organizing slightly.[2]

On October 31, the storm moved across the Mississippi Delta near Burrwood, Louisiana, and accelerated to the northeast,[3][2] influenced by an approaching upper-level trough.[5] At 1200 UTC that day, Juan attained a secondary peak of 70 mph (110 km/h). In the subsequent six hours, the storm weakened slightly, making its final landfall just west of Pensacola, Florida with winds of 65 mph (100 km/h) late on October 31.[3][2] After striking Florida, Juan turned to the north and weakened over land. After moving through Alabama, the storm became extratropical over Tennessee on November 1. Although the Atlantic hurricane best track ceased tracking the circulation at 1800 UTC that day,[3][2] Juan continued generally northward through the Ohio Valley, and the center eventually crossed into Canada. The energy from Juan helped spawn an occluded low in the Tennessee Valley, which produced more rainfall throughout the region.[5][6] An approaching cold front absorbed the remnants of Juan on November 3.[7]

Preparations

Before Juan made landfall, about 100 people evacuated around Port Arthur, Texas. In Louisiana, about 6,550 people evacuated, including only 700 of the 1,900 residents on Grand Isle; many of those who stayed behind there were trapped after the onslaught of the storm surge. About 6,000 people evacuated in Mississippi due to the threat for flooding.[8] Many schools were closed along the coast in Louisiana and Mississippi, and two beaches were closed both sides of the Brownsville, Texas shipping channel.[9] On October 28, governor Edwin Edwards declared a state of emergency for 13 Louisiana parishes,[10] while officials issued flash flood watches for 42 of Louisiana's 64 parishes.[11] Governor George Wallace also declared a state of emergency for Alabama, and shelters were opened along the coast.[12]

Due to the erratic motion and large size of Juan, tropical cyclone warnings and watches were issued for large portions of the northern Gulf Coast.[13] Around the time of landfall, hurricane warnings were issued from Port Arthur, Texas to Mobile, Alabama, with gale warnings farther to the east to Apalachicola, Florida and extending to the west to Port O'Connor, Texas.[9] The storm's quick development left people generally unprepared. National Hurricane Center forecaster Neil Frank likened Juan to "a spinning top [that] will spin around unpredictably and do whatever it wants."[14]

Impact

While on its erratic path off the northern Gulf Coast, Juan killed 12 people, nine of whom offshore due to overturned oil rigs or boats.[2] The hurricane directly caused about $1.5 billion in damage, making it the fourth costliest United States hurricane at the time without adjusting for inflation; it was behind only Hurricane Frederic of 1979, Hurricane Agnes of 1972, and Hurricane Alicia of 1983.[15] The damage total included losses to the oil industry, wrecked crops, and overall flooding damage, mostly in Louisiana.[2] According to the Federal Emergency Management Agency (FEMA), Juan injured 1,357 people, mostly to a minor extent.[16] Juan struck less than two months after Hurricane Elena hit the northern Gulf Coast, resulting in further damage to already ravaged areas.[8]

For about five days, Juan and its precursor produced gale-force winds along the northern Gulf of Mexico. The strongest winds in relation to Juan were on offshore oil rigs, with one rig recording peak sustained winds of 92 mph (148 km/h) and gusts to 110 mph (176 km/h). Juan also produced high waves that damaged several rigs, of which two were overturned.[2] One of the rigs collapsed and fell onto an adjacent rig about 35 mi (56 km) south of Leesville, Louisiana amid hurricane-force winds and high seas.[8] The collapsed rigs, built in 1956 and 1961, were designed to withstand 45 ft (14 m) waves that would accompany a 25 year storm at the time, though Juan produced waves approaching 70 ft (21 m).[17] The combination of the waves and strong winds in advance of the storm prevented early evacuation of the oil rigs.[2] A boat of evacuees overturned in the midst of the storm, killing one and hospitalizing two others; the remaining workers were rescued by the United States Coast Guard,[8] and overall the agency rescued at least 160 people.[18] While conducting a search and rescue mission, a boat named Miss Agnes capsized about 60 mi (97 km) south of Grand Isle, Louisiana; two members of the crew went missing and were presumed killed,[8] and two other occupants were rescued.[9] A jackup rig capsized near the mouth of the Mississippi River, killing three. A rescue helicopter off the coast of Louisiana caused three severe injuries when the rescue basket blew onto the evacuated oil rig amid strong winds.[8]

Because it looped twice near the coastline, Hurricane Juan brought extensive rainfall from eastern Texas to the western Florida Panhandle.[2] In Texas, the highest precipitation total was 12.84 in (326 mm) at a station southwest of Alto.[19] The highest rainfall related to Juan in the United States was 17.78 in (452 mm), recorded in Galliano, Louisiana.[5] Farther east, there were more reports of high rainfall, measured at 10.52 in (267 mm) and 12.23 in (311 mm) in Biloxi, Mississippi and Fairhope, Alabama, respectively.[19] In Florida, the highest rainfall was 11.71 in (297 mm) near Pensacola.[20] As well as the heavy rainfall, Juan produced heightened tides along the Gulf Coast, peaking at 8.2 ft (2.5 m) in Bayou Bienvenue in Louisiana. Tides peaked at around 3.3 ft (1 m) in the other coastal states, although offshore winds caused below-normal tides in western Louisiana and Texas after Juan exited the area.[2] The storm also spawned a few tornadoes, most of them weak.[16] Two were in Mississippi, each damaging a mobile home and downing several trees, and at least three occurred in Alabama, causing isolated building and tree damage.[8]

Hurricane Juan was one of the latest tropical cyclones in the year to affect Texas. The heavy rainfall from the storm caused flooding in the southeastern portion of the state, primarily in low-lying areas and along bayous. The flooding forced several roads to close, but there was minimal housing damage. Tides reached about 4 ft (1.2 m) above normal near Galveston, causing coastal flooding and closing a portion of Texas State Highway 87, but little beach erosion. Due to Juan's structure being closer to a subtropical cyclone than a typical hurricane, it produced strong winds well away from its center, with gusts of 58 mph (93 km/h) reported along the Texas coast. The winds were strong enough to knock down trees and power lines, causing power outages.[8] One person drowned in a boating accident off the Texas coast.[16]

In Mississippi, heavy rain from Juan flooded about 340 homes and businesses, mainly in the southern portion of the state. High winds and waves damaged ports in Pass Christian and Long Beach. Several boats were damaged along the coast, and the seafood industry suffered losses. Beach erosion damaged coastal roads, leaving debris and marsh grass behind when the storm passed. The total storm cost in the state was estimated at $776,000.[8] In neighboring Alabama, Juan only produced wind gusts of 40 mph (64 km/h), which caused little damage, but the storm's rainfall contributed to Mobile recording its wettest October on record. The rains caused flooding along streets and low-lying areas, but property generally escaped unscathed. The flooding did cause locally heavy crop damage; some farmers lost 50% of their soybean crop, and the pecan crop was damaged after earlier being affected by Hurricane Elena. Damage in the state was minor, estimated at over $65,000.[8]

Farther east in Florida, high waves caused flooding, beach erosion, and the loss of seawalls previously damaged by Elena. The rough surf washed away a house on Captiva Island.[8] The outskirts of Juan also spawned 15 tornadoes along the Florida Panhandle, causing $1 million in damage.[21] The tornadoes injured six people, destroyed 19 buildings, and damaged about 40 others.[8] One of the tornadoes struck Okaloosa Island and Fort Walton Beach, killing a dog and damaging two hotels along U.S. Route 98.[14]

Louisiana

Due to the cyclone's slow movement over Louisiana, it dropped over 10 in (250 mm) of rainfall across much of the southern portion of the state.[5] The intense rainfall increased levels along rivers in southwestern Louisiana. High waves and a storm surge of 5 to 8 ft (1.5 to 2.4 m) flooded low-lying and coastal areas of southeastern Louisiana.[8] The hurricane's erratic path prevented farmers from harvesting crops for three days.[22] The combination of flooding from rainfall and storm surge covered widespread areas of crop fields, mostly affecting soybean and sugar.[8] Other crops in the state had previously been harvested.[23] About 200 cattle drowned in Terrebonne Parish, and thousands were stranded.[8] Crop damage was estimated at over $304 million,[8] including $100 million to the soybean industry, with overall damage near $1 billion across the state.[24] As well as its impact on crops, Juan severely affected the shrimp industry by washing many shrimp offshore and killing others. The storm left about $2.9 million in damage to oil facilities in the state, including the cost of damaged pipelines.[23] Overall, Juan flooded about 50,000 houses in Louisiana,[21] causing $250 million in property damage.[8]

Near Port Fourchon in Lafourche Parish, the storm surge damaged portions of Louisiana Highways 1 and 3090 and flooded about 1,200 homes, some to their roofs. Two levees in the parish were washed out and one was overtopped, inundating 100 houses near Lockport. In Terrebonne Parish, the powerful storm surge swept away parked cars, knocked a home off its foundation, and damaged a 300 ft (91 m) portion of a levee. In the parish, 800 homes were flooded, and 15,000 people were left homeless. The storm surge also washed out a 6,000 ft (1,800 m) portion of the levee protecting Grand Isle, and damaged another 14,000 ft (4,300 m).[8] The levee, built in 1984, sustained $500,000 in damages,[21] which flooded the island with 4 ft (1.2 m) of ocean water.[8] Most of the island lost power, and the city hall and high school, set up as shelters, utilized generators during the storm.[9] In Jefferson Parish, which contains Grand Isle, the storm surge entered 2,233 homes and inundated about 3,100 cars. In Violet, a man drowned when he fell from his boat into a flooded canal, and another fisherman drowned in Atchafalaya Bay. The surge flooded a 3 mi (4.8 km) section of Louisiana Route 23 in Plaquemines Parish, entering several homes, as well as a portion of Route 22. Between Livingston and Ascension parishes, about 800 homes were flooded, and another 53 homes were flooded in Tangipahoa Parish. Waters from Lake Pontchartrain swept over Airline Highway and portions of a 4 ft (1.2 m) high levee, flooding 250 nearby homes. The storm surge washed out three bridges and flooded 800 homes in St. Tammany Paris, while high waters killed a man in Slidell. One man was electrocuted and killed in Arnaudville when stepping on a downed wire.[8]

While approaching its final landfall as a weak tropical storm, Juan created a storm surge of 6.5 ft (2.0 m) along the Chandeleur Islands to its west, resulting in extensive beach erosion. The island chain is an important buffer to parts of mainland Louisiana against storms, but is frequently physically manipulated by intense hurricanes. Hurricanes Danny and Elena also impacted the islands in 1985.[25] Large portions of the Louisiana coastline lost 40 to 100 ft (12 to 30 m) of beach due to the storm, with several new temporary inlets created along barrier islands.[23]

Inland and Mid-Atlantic

In the states inland from the Gulf Coast, Juan produced lighter rainfall than where its track moved across, but there were totals as high as 6.65 in (169 mm) in Arkansas.[19] Rains directly from Juan extended into the southeastern United States, reaching 11.17 in (284 mm) on Grandfather Mountain in North Carolina,[26] and through the Mid-Atlantic with totals as high as 2.82 in (72 mm) in Bakerstown, Pennsylvania.[27] Through the Midwestern United States, Juan dropped over 4 in (100 mm) of rainfall in portions of Kentucky, Michigan, and Wisconsin.[28]

The rains from Juan and the low it spawned in the Mid-Atlantic moistened grounds across the region. The hurricane's track helped bring a plume of moisture into the Mid-Atlantic, which set the stage for a major flooding event when a low pressure area stalled on November 5 west of Washington, D.C. Major flooding occurred in Virginia and West Virginia, causing $1.4 billion in damage and 62 deaths.[6][7]

Aftermath

On October 29, Louisiana Governor Edwin Edwards requested that the state's congressional delegation ask President Ronald Reagan for a disaster declaration.[29] President Reagan responded and issued a disaster declaration on November 1, which included the parishes of Ascension, Jefferson, Lafourche, Livingston, Plaquemines, Saint Bernard, Saint Charles, Saint John the Baptist, Saint Tammany, Tangipahoa, and Terrebonne, as well as the Lower Ninth Ward of New Orleans.[30] The Louisiana Department of Transportation and Development estimated that highways in the state would require $3 million in repairs from damage wrought by the hurricane.[23]

Oil companies lost two to three days of production due to being closed by the hurricane.[31] The Louisiana National Guard assisted farmers by dropping hay to stranded cattle over a two-week period.[32] The American Red Cross ran out of funds while responding to the effects of Juan and the mid-Atlantic flooding, following the previous responses to hurricanes Elena and Gloria, as well as flooding in Puerto Rico; this prompted an emergency fundraising appeal.[33] The agency had provided about $8 million worth of assistance to families in southern Louisiana.[23] Along the Apalachicola Bay, the series of hurricane strikes severely damaged the local oyster industry, leaving hundreds of oystermen out of work.[34] The high waves caused by Juan prompted the United States Minerals Management Service to recommend increased inspections on older rigs and improve evacuation plans.[17] Hurricane Juan was one in a series of hurricanes that struck Louisiana coast over many years that contributed to the loss of the coastal wetlands.[35]

See also

- Hurricane Isaac (2012) - slow-moving hurricane that struck Louisiana, causing widespread flooding

- Tropical Storm Allison - weak, slow-moving tropical storm that also caused damaging floods in Texas and Louisiana

- Other storms of the same name

References

- 1 2 Gilbert B. Clark. Hurricane Juan Preliminary Report (GIF) (Report). National Hurricane Center. p. 1. Retrieved 2014-01-29.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 Robert A. Case (1986). "Atlantic Hurricane Season of 1985" (PDF). Monthly Weather Review. American Meteorological Society. 114 (7): 1401–1403. Bibcode:1986MWRv..114.1390C. doi:10.1175/1520-0493(1986)114<1390:ahso>2.0.co;2. Retrieved 2014-01-29.

- 1 2 3 4 5 National Hurricane Center; Hurricane Research Division (July 6, 2016). "Atlantic hurricane best track (HURDAT version 2)". United States National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration. Retrieved December 8, 2016.

- ↑ Continental U.S. Hurricanes (Detailed): 1851 to 1945, 1983 to 2012 (Report). Hurricane Research Division. June 2013. Retrieved 2014-01-29.

- 1 2 3 4 David M. Roth (2013-03-06). Hurricane Juan - October 26-November 3, 1985 (Report). Weather Prediction Center. Retrieved 2014-01-29.

- 1 2 D.H. Carpenter (1990). Floods in West Virginia, Virginia, Pennsylvania, and Maryland, November 1985 (PDF) (Report). Water-Resources Investigations Report. United States Geological Survey. Retrieved 2014-02-09.

- 1 2 Peter Corrigan (2010-11-04). The Floods of November, 1985: Then and Now (PDF) (Report). Blacksburg, Virginia National Weather Service. Retrieved 2014-02-04.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 19 20 "Storm Data". 27 (10). National Climatic Data Center. October 1985: 16, 21–24, 28–29. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2014-04-21. Retrieved 2014-01-30.

- 1 2 3 4 "Hurricane Threatens Gulf Coast; 2 Are Missing After Boat Capsizes". New York Times. Associated Press. 1985-10-28. Retrieved 2014-02-01.

- ↑ "Hurricane Juan Kills 3 As It Batters Gulf Coast". New York Times. Associated Press. 1985-10-28. Retrieved 2014-02-23.

- ↑ "Hurricane Juan Batters Louisiana". The Blade. Toledo, Ohio. Associated Press. 1985-10-28. Retrieved 2014-02-26.

- ↑ "Erratic Storm Returns to the Gulf, Then Veers Inland Over Alabama". New York Times. Associated Press. 1985-11-01. – via Lexis Nexis (subscription required)

- ↑ Gilbert B. Clark. Hurricane Juan Preliminary Report (GIF) (Report). National Hurricane Center. p. 4. Retrieved 2014-02-01.

- 1 2 Storer Rowley (1985-10-29). "1 Dead, 3 Lost As Hurricane Slams Oil Rigs". Chicago Times. Retrieved 2014-02-01.

- ↑ Paul J. Hebert; Robert A. Case (March 1990). The Deadliest, Costliest, and Most Intense United States Hurricanes of This Century (and Other Frequently Requested Hurricane Facts) (PDF) (Report). National Hurricane Center. p. 7. Retrieved 2014-01-29.

- 1 2 3 Gilbert B. Clark. Hurricane Juan Preliminary Report (GIF) (Report). National Hurricane Center. p. 3. Retrieved 2014-01-30.

- 1 2 "Structural check urged for U.S. gulf platforms". Oil and Gas Journal. 1988-01-18. – via Lexis Nexis (subscription required)

- ↑ "Hurricane Makes Return Visit to Shore and Stalls". New York Times. 1985-10-30. – via Lexis Nexis (subscription required)

- 1 2 3 David M. Roth (2013-03-06). Tropical Cyclone Rainfall for the Gulf Coast (Report). Weather Prediction Center. Retrieved 2014-01-29.

- ↑ David M. Roth (2013-03-06). Tropical Cyclone Rainfall for Florida (Report). Weather Prediction Center. Retrieved 2014-01-30.

- 1 2 3 "Hurricane Juan Flooding Still a Threat". Lewiston Daily Sun. Associated Press. 1985-11-02. Retrieved 2014-02-26.

- ↑ "National Weather Summary" (PDF). Weekly Weather and Crop Bulletin. United States Department of Agriculture. 72 (44). 1985-11-05. Retrieved 2014-02-18.

- 1 2 3 4 5 United States Minerals Management Service (1996). Proposed oil and gas lease sales 110 and 112, Gulf of Mexico OCS Region: draft environmental impact statement (Report). United States Department of the Interior. pp. D7–D19. Retrieved 2014-03-11.

- ↑ Janet McConnaughey (1985-11-02). "Louisiana Surveys Hurricane's Flood Damage". Associated Press. – via Lexis Nexis (subscription required)

- ↑ Sarah Fearnley; et al. (2009). "Hurricane Impact and Recovery Shoreline Change Analysis and Historical Island Configuration: 1700s to 2005" (PDF). United States Geological Survey. p. 20. Retrieved 2014-03-04.

- ↑ David M. Roth (2013-03-06). Tropical Cyclone Rainfall in the Southeast (Report). Weather Prediction Center. Retrieved 2014-01-30.

- ↑ David M. Roth (2013-03-06). Tropical Cyclone Rainfall in the Mid-Atlantic (Report). Weather Prediction Center. Retrieved 2014-01-30.

- ↑ David M. Roth (2013-03-06). Tropical Cyclone Rainfall in the Midwest (Report). Weather Prediction Center. Retrieved 2014-01-30.

- ↑ Michael L. Graczyk (1985-10-30). "Juan grew too fast to evacuate offshore workers, officials say". Evening Independent. Houston, Texas. Associated Press. p. 3. Retrieved 2013-02-06.

- ↑ United States Department of Homeland Security (2004-11-23). "Louisiana Hurricane Juan". Federal Emergency Management Agency. Archived from the original on January 3, 2012. Retrieved 2012-06-23.

- ↑ "Domestic Crude". Platt's Oilgram Price Report. 1985-10-31. – via Lexis Nexis (subscription required)

- ↑ "National Guard Dropping Hay to Stranded Cattle". Associated Press. 1985-11-09. – via Lexis Nexis (subscription required)

- ↑ Sandy Johnson (1985-11-08). "Disaster-Filled Year Drains Red Cross Relief Fund". Associated Press. – via Lexis Nexis (subscription required)

- ↑ "Apalachicola Still Gives Thanks After Taking Beatings By Hurricanes". Ocala Star-Banner. 1985-11-29. Retrieved 2014-02-27.

- ↑ Austin Wilson (1989-06-21). "'First Line of Defense' for Wetlands Is Also Vanishing". Associated Press. – via Lexis Nexis (subscription required)