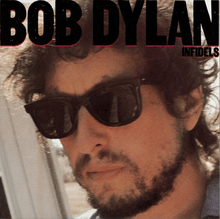

Infidels (Bob Dylan album)

| Infidels | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| ||||

| Studio album by Bob Dylan | ||||

| Released | October 27, 1983 | |||

| Recorded | April–May 1983 at the Power Station, New York | |||

| Genre | Heartland rock | |||

| Length | 41:39 | |||

| Label | Columbia | |||

| Producer | Bob Dylan, Mark Knopfler | |||

| Bob Dylan chronology | ||||

| ||||

Infidels is the twenty-second studio album by American singer-songwriter Bob Dylan, released on October 27, 1983 by Columbia Records.

Produced by Mark Knopfler and Dylan himself, Infidels is seen as his return to secular music, following a conversion to Christianity, three evangelical, gospel records and a subsequent return to a less religious lifestyle. Though he has never abandoned religious imagery, Infidels gained much attention for its focus on more personal themes of love and loss, in addition to commentary on the environment and geopolitics. Christopher Connelly of Rolling Stone called those gospel albums just prior to Infidels "lifeless", and saw Infidels as making Bob Dylan's career viable again. According to Connelly and others, Infidels is Dylan's best poetic and melodic work since Blood on the Tracks.[1]

The critical reaction was the strongest for Dylan in years, almost universally hailed for its songwriting and performances. The album also fared well commercially, reaching #20 in the US and going gold, and #9 in the UK. Still, many fans and critics were disappointed that several songs were inexplicably cut from the album just prior to mastering—primarily "Blind Willie McTell", considered a career highlight by many critics, and not officially released until it appeared on The Bootleg Series Volume III eight years later.

Recording sessions

Infidels was produced by Mark Knopfler, best known as the frontman of the band Dire Straits. Dylan initially wanted to produce the album himself, but feeling that technology had passed him by, he approached a number of contemporary artists who were more at home in a modern recording studio. David Bowie, Frank Zappa, and Elvis Costello were all approached before Dylan hired Knopfler.[2]

Knopfler later admitted it was difficult to produce Dylan. "You see people working in different ways, and it's good for you. You have to learn to adapt to the way different people work. Yes, it was strange at times with Bob. One of the great parts about production is that it demonstrates to you that you have to be flexible. Each song has its own secret that's different from another song, and each has its own life. Sometimes it has to be teased out, whereas other times it might come fast. There are no laws about songwriting or producing. It depends on what you're doing, not just who you're doing. You have to be sensitive and flexible, and it's fun. I'd say I was more disciplined. But I think Bob is much more disciplined as a writer of lyrics, as a poet. He's an absolute genius. As a singer—absolute genius. But musically, I think it’s a lot more basic. The music just tends to be a vehicle for that poetry."

Once Knopfler was aboard, the two quickly assembled a team of accomplished musicians. Knopfler's own guitar playing was paired with that of Mick Taylor, a former lead guitarist of the Rolling Stones. Having been introduced to Taylor the previous summer, Dylan had developed a friendship with him that resulted in the guitarist hearing the Infidels material first during the months leading up to the April sessions.[3] In addition, the sessions benefited as well from Taylor's ability as a slide guitarist.

Knopfler said about the instrument he plays on Infidels: "I still haven't got a flat-top wooden acoustic, because I've never found one that was as good as the two best flat tops I ever played. One … was a hand-built Greco that Rudy Pensa, of Rudy's Music Stop lent me. I used … the Greco on Infidels."

Knopfler suggested Alan Clark for keyboards as well as engineer Neil Dorfsman, both of whom were hired. According to Knopfler, it was Dylan's idea to recruit Robbie Shakespeare and Sly Dunbar as the rhythm section. Best known as Sly & Robbie, Shakespeare and Dunbar were famed reggae producers as well as recording artists in their own right.

"Bob's musical ability is limited, in terms of being able to play a guitar or a piano," said Knopfler. "It's rudimentary, but it doesn't affect his variety, his sense of melody, his singing. It's all there. In fact, some of the things he plays on piano while he's singing are lovely, even though they're rudimentary. That all demonstrates the fact that you don't have to be a great technician. It's the same old story: If something is played with soul, that's what's important."

Songs

Beginning with Infidels, Dylan ceased to preach a specific religion, revealing little about his personal religious beliefs in his lyrics. In 1997, after recovering from a serious heart condition, Dylan said in an interview for Newsweek, "Here's the thing with me and the religious thing. This is the flat-out truth: I find the religiosity and philosophy in the music. I don't find it anywhere else … I don't adhere to rabbis, preachers, evangelists, all of that. I've learned more from the songs than I've learned from any of this kind of entity."[4]

Though Infidels is often cited as a return to secular work (following a trio of albums heavily influenced by born-again Christianity), many of the songs recorded during the Infidels sessions retain Dylan's penchant for Biblical references and religious imagery.[5] An example of this is the opening track, "Jokerman". Along with Biblical references, the song's lyrics reference populists who are overly concerned with the superficial ("Michelangelo indeed could've carved out your features") and more about action than thinking through the complexities ("fools rush in where angels fear to tread"). A number of critics have called Jokerman a sly political protest, addressed to an antichrist-like[6] figure, a "manipulator of crowds … a dream twister."

The second track, "Sweetheart Like You", is sung to a fictitious woman. Oliver Trager's book, Keys to the Rain: The Definitive Bob Dylan Encyclopedia, mentions that some have criticized this song as sexist. Indeed, music critic Tim Riley makes that accusation in his book, Hard Rain: A Dylan Commentary, singling out lyrics like "a woman like you should be at home/That's where you belong/Taking care of somebody nice/Who don't know how to do you wrong." However, Trager also cites other interpretations that dispute this claim.[7] Some have argued that "Sweetheart Like You" is being sung to the Christian church ("what's a sweetheart like you doing in a dump like this?"), claiming that Dylan is mourning the church's deviation from scriptural truth. The song was later covered by Rod Stewart on his 1995 album A Spanner in the Works and translated and sung by the Italian songwriter Francesco De Gregori in his 2015.

A few critics like Robert Christgau and Bill Wyman claimed that Infidels betrayed a strong, strange dislike for space travel, and it can be heard on the first few lines of "License to Kill". ("Man has invented his doom/First step was touching the moon.") A harsh indictment accusing mankind of imperialism and a predilection for violence, the song deals specifically with humanity’s relationship to the environment, either on a political scale or a scientific one, beginning with the first line: "Man thinks because he rules the Earth/He can do with it as he please." A skeptical opinion toward the American space program was shared among other evangelicals of Dylan's generation.[8]

The song "Neighborhood Bully" is a song from the point of view of someone using sarcasm to defend Israel's right to exist; the title bemoans Israel's and the Jewish People's historic treatment in the populist press. Events in the history of the State of Israel are referenced, such as the Six-Day War and Operation Opera, Israel's bombing of the Osirak nuclear reactor near Baghdad on June 7, 1981, or previous bomb making sites bombed by Israeli soldiers. Events in the history of the Israelites as a whole are mentioned, such as being enslaved by Rome (commemorated on the Arch of Titus, and extensively in the Jewish Talmud[9]), Egypt (remembered on the Jewish holiday Passover, and the Book of Exodus), and Babylon (commemorated on the Jewish holiday Tisha B'Av and the Book of Lamentations). Events in modern Jewish secular history are noted as well, such as the ridiculing of holy books by anti-semitic groups like the Nazis and the Soviet Union, and Jews' historic role in the advancement of medicine ("took sickness and disease and turned them into health"). Historic restrictions on Jewish commerce are mentioned as well.[10] In 1983, Dylan visited Israel again, but for the first time allowed himself to be photographed there, including a shot at Jerusalem's open-air synagogue wearing a yarmulkah and orthodox Jewish phylactories, and tallith. Dylan made some roundabout comments on the song in a 1984 interview with Rolling Stone.[11] In 2001, the Jerusalem Post described the song as "a favorite among Dylan-loving residents of the territories".[12] Israeli singer Ariel Zilber covered "Neighborhood Bully" in 2005 in a version translated to Hebrew.[13]

"Union Sundown" is a political protest song against imported consumer goods and offshoring. In the song, Dylan examines the subject from several different angles, discussing the greed and power of unions and corporations ("You know capitalism is above the law,/ It don't count unless it sells./ When it costs too much to build it at home you just build it cheaper someplace else." ... "Democracy don't rule this world,/ You better get that through your head./ This world is ruled by violence/Though I guess that's better left unsaid."), the hypocrisy of Americans who complain about the lack of American jobs while not paying more for American-made products ("Lots of people complainin' that there is no work./I say, 'Why you say that for? When nothin' you got is U.S.-made? They don't make nothin' here no more"), the collaboration of the unions themselves ("The unions are big business, friend'/ And they’re goin’ out like a dinosaur."), and the desperate conditions of the foreign workers who make the goods ("All the furniture, it says “Made in Brazil”/ Where a woman, she slaved for sure/ Bringin’ home thirty cents a day to a family of twelve/ You know, that’s a lot of money to her." ... "And a man's going to do what he has to do,/ When he's got a hungry mouth to feed.").

"I and I", according to author/critic Tim Riley, "updates the Dylan mythos. Even though it substitutes self-pity for the [pessimism found throughout Infidels], you can't ignore it as a Dylan spyglass: 'Someone else is speakin' with my mouth, but I'm listening only to my heart/I've made shoes for everyone, even you, while I still go barefoot.'"[14] Riley sees the song as an exploration of the distance between Dylan's "inner identity and the public face he wears".[7]

Infidels' closer, "Don't Fall Apart On Me Tonight" stands out on the album as a pure love song. On past albums like John Wesley Harding and Nashville Skyline, Dylan closed with love songs sung to the narrator's partner, and that tradition is continued with "Don't Fall Apart On Me Tonight", with a chorus that asks "Don't fall apart on me tonight, I just don't think that I could handle it./Don't fall apart on me tonight, Yesterday's just a memory, Tomorrow is never what it's supposed to be/And I need you, yeah, you tonight."

Final sequencing and mixing

While Dylan was known to be prolific and had numerous outtakes for most of his albums, Infidels in particular garnered considerable controversy over the years regarding its final selection of songs. By June 1983, Dylan and Knopfler had set a preliminary sequence of nine songs, including two songs that were ultimately omitted: "Foot Of Pride" and "Blind Willie McTell". Other notable outtakes like "Someone's Got A Hold Of My Heart" (later re-written and re-recorded for Empire Burlesque as "Tight Connection to My Heart (Has Anyone Seen My Love)") were recorded during these sessions, but only "Foot Of Pride" and "Blind Willie McTell" received serious consideration for possible inclusion.

"Blind Willie McTell" is perhaps the most heatedly discussed outtake in Dylan's catalog. "On the surface, 'Blind Willie McTell' is about the landscape of the blues," writes Tim Riley, "and the figures Dylan pays respects to on his 1962 debut. But it's also about the landscape of pop, and how an aging persona like Dylan might feel as he casts his experienced gaze over the road he's walked. Always skeptical about the quality of his own voice, he didn't release 'Blind Willie McTell' at first because he didn't feel his tribute lived up to its sources. The irony here is that his own insecurity about living up to his imagined blues ideal becomes a subject in itself. 'Nobody sings the blues like Blind Willie McTell' becomes a way of saying how Dylan feels displaced not just by the industry … but by the music he calls home." Clinton Heylin gives "Blind Willie McTell" a more ambitious interpretation, describing it as "the world's eulogy, sung by an old bluesman recast as St. John the Divine".

Both "Foot Of Pride" and "Blind Willie McTell" were dropped from consideration soon after Mark Knopfler ended his involvement with the album. In later years, Knopfler claimed that "Infidels would have been a better record if I had mixed the thing, but I had to go on tour in Germany, and then Bob had a weird thing with CBS, where he had to deliver records to them at a certain time and I was away in Europe … Some of [Infidels] is like listening to roughs. Maybe Bob thought I'd rushed things because I was in a hurry to leave, but I offered to finish it after our tour. Instead, he got the engineer to do the final mix."[15]

Dylan spent roughly a month on remixing and overdubbing, holding a number of sessions in June rerecording vocal tracks using newly rewritten lyrics. During this time, he decided to cast aside "Foot Of Pride" and "Blind Willie McTell", replacing them with "Union Sundown".

Outtakes

As with most Dylan albums, outtakes and rough mixes from Infidels were eventually bootlegged. This is a partial listing of known outtakes. All titles in parentheses are "working titles".

|

|

|

Also, alternate versions of every song on Infidels are in circulation as well. None of these alternate takes has been commercially released.

- "Jokerman"

- "Sweetheart Like You" (alternate version 1)

- "Sweetheart Like You" (alternate version 2)

- "Sweetheart Like You" (Several rehearsals)

- "Neighborhood Bully" (alternate version)

- "License To Kill" (alternate version)

- "Man Of Peace" (alternate version)

- "Union Sundown" (alternate version 1)

- "Union Sundown" (alternate version 2)

- "I And I" (alternate version)

- "Don't Fall Apart On Me Tonight" (alternate version)

Reception

| Professional ratings | |

|---|---|

| Review scores | |

| Source | Rating |

| AllMusic | |

| Robert Christgau | B- [17] |

| Entertainment Weekly | A- [18] |

| MusicHound | |

| Paste | (Positive) [20] |

| Rolling Stone | |

While Infidels was better received than its predecessor, Shot of Love, Graham Lock of New Musical Express still referred to Dylan as "culturally a spent force … a confused man trying to rekindle old fires."[22] Rolling Stone and The Village Voice critic Robert Christgau was not impressed either, writing that Dylan had "turned into a hateful crackpot".[23] Greil Marcus dismissed it many years later as another "bad [album] that made no sense, didn't hang together, had no point, and did not need to exist".[24]

But even some of the skeptics found some merit in Infidels. In the same review, Christgau wrote, "All the wonted care Dylan has put into this album shows." Indeed, critics were unanimous in praising the overall sound, "one case where the streamlined production doesn't seem to work against the rugged authority he can still command as a singer," wrote Tim Riley. Music critic Bill Wyman conceded that "the songs are mature and complex" even though "melodically they are similar sounding and the affair as a whole still has echoes of his crackpot Christian days."[25]

Infidels would place tenth on The Village Voice's Pazz & Jop Critics Poll for 1983, Dylan's highest placement since 1975 when The Basement Tapes placed #1 and Blood on the Tracks placed #4. Years later, when outtakes like "Someone's Got A Hold Of My Heart", "Blind Willie McTell", and "Foot Of Pride" began to circulate, the album's stature would in some ways grow, becoming a missed opportunity at a potential masterpiece to some critics like Rob Bowman and Clinton Heylin.

Without a tour in 1983, Infidels still generated modest sales, selling consistently through the Christmas shopping season. CBS even produced a music video for "Sweetheart Like You", Dylan's first in the MTV era. Steve Ripley from Dylan's Shot of Love band was one of the guitarists in the video. The female guitar player featured and who mimed Mick Taylor's guitar solo is Carla Olson. This appearance led to her recording a live album with Mick as well as numerous studio sessions with him. And Dylan gave her the unreleased song "Clean Cut Kid" for her debut album Midnight Mission (A&M Records). "Sweetheart Like You" was followed by a second video for "Jokerman", which CBS issued as a single in February 1984.

Aftermath

Dylan spent the fall of 1983 recording demos and various songs at his home in Malibu, California. Rather than work alone, Dylan brought in a number of young musicians, including Charlie Sexton, drummer Charlie Quintana, and guitarist JJ Holiday. As Heylin notes, "this was Dylan's first real dalliance with third-generation American rock & rollers." These informal sessions set the stage for Dylan's first public performances since 1982.

Dylan appeared on Late Night with David Letterman on March 22, 1984. He performed with Quintana, Holiday (introduced by Letterman as "Justin Jesting"), and bassist Tony Marsico. Performing three songs with his band of post-punk musicians, the Plugz, Dylan delivered what many consider to be his most entertaining television performance ever. The combo first performed an unrehearsed version of Sonny Boy Williamson's "Don't Start Me To Talking", then a radically different arrangement of "License To Kill". The final song was a peppy, somewhat new-wave version of "Jokerman" that ended with a harmonica solo. At the end of the performance, Letterman walked onstage and congratulated Dylan, asking him if he could come back and play every Thursday. Dylan smiled and jokingly agreed.[26]

Track listing

All songs written by Bob Dylan.

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Personnel

Additional musicians

- Alan Clark – keyboards

- Sly Dunbar – drums, percussion

- Clydie King – vocals on "Union Sundown"

- Mark Knopfler – guitar, production

- Robbie Shakespeare – bass guitar

- Mick Taylor – guitar

See also

References

- ↑ Connelly, Christopher (November 24, 1983). "Infidels Album Review". Rolling Stone. Retrieved 20 November 2013.

- ↑ Heylin, Clinton (1991). Bob Dylan: Behind the Shades Revisited, p. 550. HarperCollins (2003 paperback ed.) ISBN 0-06-052569-X.

- ↑ Heylin (1991), p. 551.

- ↑ Gates, David (October 6, 1997). "Dylan Revisited". Newsweek. Retrieved 2009-01-10.

- ↑ Balassone, Damian (April 4, 2012) "Jokerman"

- ↑ Balassone, Damian (October 29, 2010) "Dylan, the Devil and Judas", Overland.

- 1 2 Riley, Tim (1992). Hard Rain: A Dylan Commentary, pp. 271-72. New York: Da Capo Press (updated edition, 1999). ISBN 0-306-80907-9.

- ↑ This was most famously articulated by contemporary Christian music icon Larry Norman, whose songs declared variously "you say you beat the Russians to the Moon but I say you starved your children to do it" and "We need a solution/We need salvation/Let's send some people to the moon to gather information/And all they brought back was a big bag of rocks/Only cost 13 billion/Must be nice rocks".

- ↑ Examples in the Talmud include rabbis like Aqiba and Simon Bar Yohai getting tortured by the Roman Empire and their students enslaved, see wiki references to their names for the accounts in the Jewish oral history

- ↑ In most Christian law systems "Jews were barred from all guilds and were only allowed two positions, that of money lending and the selling of used clothing." see Edward Flannery's "The Anguish of the Jews" or any other well researched book on anti-Semitism

- ↑ "News". Rolling Stone. Retrieved 2012-02-25.

- ↑ David Brinn, "Brilliant when he sings", Jerusalem Post, 7 December 2001, 12B.

- ↑ Zilber's version made use of the original text but is commonly taken as referring to Israel's unilateral disengagement plan, the subject of several other songs in the album, Anabel.

- ↑ Quoted in Trager, Oliver (2004). Keys to the Rain: The Definitive Bob Dylan Encyclopedia, p. 270. New York: Billboard Books. ISBN 0-8230-7974-0.

- ↑ Quoted in Heylin (1991), p. 555.

- ↑ link

- ↑ {{http://www.robertchristgau.com/get_artist.php?name=Bob+Dylan}}

- ↑ Flanagan, Bill (1991-03-29). "Dylan Catalog Revisited". EW.com. Retrieved 2012-08-20.

- ↑ Graff, Gary; Durchholz, Daniel (eds) (1999). MusicHound Rock: The Essential Album Guide (2nd ed.). Farmington Hills, MI: Visible Ink Press. p. 371. ISBN 1-57859-061-2.

- ↑ {{http://www.pastemagazine.com/articles/2013/11/bob-dylan-the-complete-albums-collection.html}}

- ↑ Connelly, Christopher (November 24, 1983). "Infidels Album Review". Rolling Stone. Retrieved 20 November 2013.

- ↑ Quoted in Heylin (1991), p. 557.

- ↑ "CG: Bob Dylan". Robert Christgau. Retrieved 2012-02-25.

- ↑

- ↑ Wyman, Bill. "Bob Dylan – Bill Wyman". Salon.com. Retrieved 2012-02-25.

- ↑ Heylin (1991), pp. 560-61.