Inland Northern American English

Inland Northern (American) English,[1] also known in the United States as the Inland North or Great Lakes dialect,[2] is an American English dialect spoken in a geographic band reaching from Central New York westward along the Erie Canal, through most of the U.S. Great Lakes region, to eastern Iowa. The most advanced Inland Northern accents are spoken in the cities of Chicago, Illinois; Milwaukee, Wisconsin; Detroit, Michigan; Cleveland, Ohio; and Buffalo, Rochester, and Syracuse, New York.[3] A geographic corridor that extends across a section of Illinois, reaching from Chicago into St. Louis, Missouri, has also been infiltrated by features of the Inland Northern accent, though not historically part of the Inland North dialect region.

Distribution

The dialect region called the "Inland North" consists of western and central New York State (Utica, Syracuse, Rochester, Buffalo, Binghamton, Jamestown, Fredonia, Olean); northern Ohio (Akron, Cleveland, Toledo); Michigan's Lower Peninsula (Detroit, Flint, Grand Rapids, Lansing); northern Indiana (Gary, South Bend); northern Illinois (Chicago, Rockford); southeastern Wisconsin (Kenosha, Racine, Milwaukee); and, largely, northeastern Pennsylvania's Wyoming Valley/Coal Region (Scranton, Wilkes-Barre). This is the dialect spoken in part of America's chief industrial region, an area sometimes known as the Rust Belt.

Erie, Pennsylvania, though in the geographic area of the "Inland North," never underwent the Northern Cities Shift and now shares more features with Western Pennsylvania English. Meanwhile, in suburban areas, the dialect may be less pronounced, for example, native-born speakers in Kane, McHenry, Lake, DuPage, and Will Counties in Illinois may sound slightly different from speakers from Cook County and particularly those who grew up in Chicago. Many African-Americans in Detroit and other Northern cities are multidialectal and also or exclusively use African American Vernacular English rather than Inland Northern English, but some do use the Inland Northern dialect, as do almost all people in and around the city of Detroit who are not African Americans.

History

The dialect's origins lie in the early 19th century, when speakers around the Great Lakes began to pronounce the short 'a' sound (/æ/, as in "bat") as more of a diphthong with a starting point higher in the mouth, causing the same word to sound more like "bay-at". This development stayed largely stagnant for about a century, but around the 1960s, speakers began to use the newly opened space for the short 'o' sound (/ɒ/, as in "bot"), which then came to be pronounced with a tongue extended farther forward and sound more like "bat". Several more vowels proceeded in rapid succession, each filling in the space left by the last, and residents across the region are continuing to develop more and more features of the dialect.[4]

The unique short-a system of the Inland Northern dialect region remains today, having gradually spread westward throughout the Great Lakes cities, and no further developments occurred in the accent for about a century, until the 1960s, when this region's speakers began to use the newly opened vowel space (i.e., previously occupied by [æ]), for the short o vowel /ɒ/, as in bot, gosh, or lock, which then came to be pronounced with a tongue extended farther forward, making these words sound more like bat, gash, and lack. This vowel change was first reported in 1967, with several more vowels following suit in rapid succession, each filling in the space left by the last, including the backing of /ʌ/ (as in bug, luck, or pup), first reported in 1986;[5] altogether, this constitutes a chain shift of vowels, identified as such in 1972, and known by linguists as the Northern Cities Shift: the defining pattern of the Inland Northern accent. Residents across the region are continuing to develop more and more features of the dialect.[4]

The dialect's progression across the Midwest has, however, stopped at a general boundary line traveling through central Ohio, Indiana, and Illinois and then western Wisconsin, on the other sides of which speakers have continued to maintain their Midland and North Central accents. Sociolinguist William Labov theorizes that this separation reflects a political divide: Inland Northern speakers tend to be more politically liberal—and be perceived as such in controlled studies—than those of the other dialects, especially as Americans continue to self-segregate in residence based on ideological concerns. Paul Ryan, the 54th Speaker of the U.S. House of Representatives and vice presidential candidate running with Mitt Romney in 2012, is a rare example of a prominent Republican politician demonstrating features of the dialect.[4]

Characteristics

Phonology and phonetics

| Pure vowels (Monophthongs) | ||

|---|---|---|

| English diaphoneme | Inland Northern phoneme | Example words |

| /æ/ | eə~ɪə | bath, trap, man |

| /ɑː/ | a~ä | blah, bother, father, lot, top, wasp |

| /ɒ/★ | ||

| ɒ(ː) | all, dog, bought, loss, saw, taught | |

| /ɔː/ | ||

| /ɛ/ | ɛ~ɜ | dress, met, bread |

| /ə/ | ə | about, syrup, arena |

| /ɪ/ | ɪ~ɪ̈ | hit, skim, tip |

| /iː/ | ɪi~i | beam, chic, fleet |

| /ɨ/ | ɪ~ɪ̈~ə | island, gamut, wasted |

| /ʌ/ | ʌ~ɔ | bus, flood, what |

| /ʊ/ | ʊ | book, put, should |

| /uː/ | u~ɵu | food, glue, new |

| Diphthongs | ||

| /aɪ/ | ae~aɪ~æɪ | ride, shine, try |

| ɐɪ~ɐi | bright, dice, fire | |

| /aʊ/ | äʊ~ɐʊ | now, ouch, scout |

| /eɪ/ | eɪ | lame, rein, stain |

| /ɔɪ/ | ɔɪ | boy, choice, moist |

| /oʊ/ | ʌo~oʊ~o | goat, oh, show |

| R-colored vowels | ||

| /ɑr/ | äɻ~ɐɻ | barn, car, park |

| /ɪər/ | iɻ~iɚ | fear, peer, tier |

| /ɛər/ | eɪɻ | bare, bear, there |

| /ɜr/ | əɻ~ɚ | burn, doctor, first, herd, learn, murder |

| /ər/ | ||

| /ɔr/ | ɔɻ~oɻ | hoarse, horse, poor score, tour, war |

| /ɔər/ | ||

| /ʊər/ | ||

| /jʊər/ | jəɻ~jɚ | cure, Europe, pure |

| ★ Footnotes When followed by /r/, the phoneme /ɒ/ is pronounced entirely differently by Inland North speakers as [ɔ~o], for example, in the words orange, forest, and torrent. The only exceptions to this are the words tomorrow, sorry, sorrow, borrow and, for some speakers, morrow, which use the sound [a~ä]. | ||

A Midwestern accent (which may refer to other dialectal accents as well), Chicago accent, or Great Lakes accent are all common names in the United States for the sound quality produced by speakers of this dialect. Many of the characteristics listed here are not necessarily unique to the region and are oftentimes found elsewhere in the Midwest.

- Rhoticity: As in General American, Inland North speech is rhotic, and the "r" sound is typically the retroflex (or perhaps, more accurately, the bunched or molar) [ɻ].

- Mary–marry–merry merger: Words containing /æ/, /ɛ/, or /eɪ/ before an r and a vowel are all pronounced "[ɛ~eɪ]-r-vowel", so that Mary, marry, and merry all sound the same, and have the same first vowel as Sharon, Sarah, and bearing. This merger is widespread throughout the Midwest, West, and Canada.

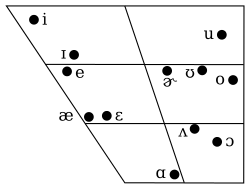

- Northern Cities Vowel Shift: This chain shift is found primarily in the Inland North—in fact, it is the feature that largely defines the Inland North, for modern dialectological purposes. Note that this shift is in progress across the region, but that each subsequent stage is a result of the previous one(s), so that an individual speaker may not display all of these shifts, but no speakers will display the last without also showing the ones before it. This vowel shift has been occurring in six stages:

- The first and most common stage of the shift is the raising, fronting, and "breaking" of /æ/ universally (i.e., every instance of the "short a," thus, in words like cat, trap, bath, staff, etc.), which therefore comes to be realized as a tensed diphthong of the type [eə] or [ɪə]; e.g. "naturally."

- The second stage is the fronting of /ɒ/, which in most American accents is [ɑ~ä], towards [a~æ]—in words like not, wasp, blah, and coupon (

[ˈkʰupan])—which occupies a place close to (but opener than) the former /æ/.

[ˈkʰupan])—which occupies a place close to (but opener than) the former /æ/. - In the third stage, /ɔː/ (in words like law, thought and all) lowers towards [ɑ] or [ɒ]; with Inland North speakers, this is more precisely [ɒ(ː)], since they front the Middle English /ɒ/ phoneme (e.g., in "rod") to [a], thus maintaining a distinction between words like cot [kʰat] and caught [kʰɒːt].[7] However, there is a definite scattering of Inland North speakers who are in a state of transition towards a cot–caught merger; this is particularly noticeable in northeastern Pennsylvania.[8][9]

- The fourth stage is the backing and lowering of /ɛ/, almost towards [ɐ].

- During the fifth stage, /ʌ/ (in words like cut, mud and luck) is backed in the mouth.

- In the sixth stage, /ɪ/ (in words like if, bib and pin) is lowered and backed, although it is kept distinct from /ɛ/ in all phonetic environments, so the pin–pen merger does not occur.

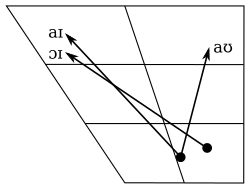

- Canadian raising: Two phenomena typically exist, corresponding with identical phenomena in Canadian English, involving tongue-raising in the nuclei (beginning points) of gliding vowels that start in an open front (or central) unrounded position:

- The raising of the tongue for the nucleus of the gliding vowel /aɪ/ is found in the Inland North when the vowel sound appears before any voiceless consonant, just like in General American, thus distinguishing, for example, between writer and rider (

listen).[10] However, unlike General American, the raising occurs even before certain voiced consonants, including in the words fire, tiger, iron, and spider. When it is not subject to raising, the nucleus of /aɪ/ is pronounced with the tongue further to the front of the mouth as [a̟ɪ] or [ae]; however, in the Inland North speech of Pennsylvania alone, the nucleus is centralized, thus: [äɪ].[11]

listen).[10] However, unlike General American, the raising occurs even before certain voiced consonants, including in the words fire, tiger, iron, and spider. When it is not subject to raising, the nucleus of /aɪ/ is pronounced with the tongue further to the front of the mouth as [a̟ɪ] or [ae]; however, in the Inland North speech of Pennsylvania alone, the nucleus is centralized, thus: [äɪ].[11] - The nucleus of /aʊ/ may be more backed than in other common North American accents (towards [ɐʊ] or [äʊ]).

- The raising of the tongue for the nucleus of the gliding vowel /aɪ/ is found in the Inland North when the vowel sound appears before any voiceless consonant, just like in General American, thus distinguishing, for example, between writer and rider (

- The nucleus of /oʊ/ (as in go and boat), remains a back vowel [oʊ~ʌo], not undergoing the fronting that is common in other American dialects, such as Southern and Midland American English. Similarly, the traditionally high back vowel /uː/ tends to be conservative and less fronted in the North than in other regions, though it still undergoes some fronting after coronal consonants: [ɵu].[12]

- /ɑːr/ (as in bar, sorry, or start) is centralized or fronted for many speakers in this region, resulting in variants like [äɻ~ɐɻ].

- Working-class th-stopping: The two sounds represented by the spelling th—/θ/ (as in thin) and /ð/ (as in those)—may shift from fricative consonants to stop consonants among urban and working-class speakers: thus, for example, thin may approach the sound of tin (using [t]) and those may merge to the sound of doze (using [d]).[13] This was parodied in the comedy sketch "Bill Swerski's Superfans," in which characters hailing from Chicago pronounce "The Bears" as "Da Bears."

Vocabulary

Note that not all of these are specific to the region.

- Faucet vs. Southern spigot.

- (Peach) Pit vs. Southern stone or seed.

- Pop for soft drink, vs. East-Coastal and Californian soda and Southern coke. The "soda/pop line" has been found to run between Western and Central New York State (Buffalo residents say "pop", Syracuse residents who used to say "pop" until sometime in the 1970s now say "soda", and Rochester residents say either. Lollipops are also known as "suckers" in this region.) as well as in parts of eastern Wisconsin.

- Shopping cart vs. Southern buggy.

- Teeter totter vs. Southern seesaw.

- Tennis shoes or gym shoes vs. Northeast sneakers.

Individual cities and regions also have their own vocabularies; for example:

- In a large portion of southern and eastern Wisconsin, drinking/water fountains are known as bubblers.

- In the Chicago area, sneakers are often known as gym shoes and the ATM is known as the "cash station".

- In Michigan, convenience stores are called party stores

- In Detroit, sliding glass doors may be called doorwalls

- In Buffalo, Rochester, Syracuse, Utica, Binghamton (all New York), as well as Scranton (Pennsylvania), athletic/tennis shoes are often called sneakers.

- In Cleveland, the road verge (grass between the sidewalk and the street) is called a tree lawn, whereas in nearby Akron the same space is called a devilstrip.

- In northeastern Pennsylvania, surrounding and including its urban center of Scranton, the plural of you (typically you guys or simply you in most of the Inland North and the rest of the country) are commonly heard to be yous(e).

Notable lifelong native speakers

- Hillary Clinton – "playing down her flat Chicago accent"[14]

- Joan Cusack — "a great distinctive voice" she says is due to "my Chicago accent... my A's are all flat"[15]

- Richard M. Daley — "makes no effort to tame a thick Chicago accent"[16]

- Kevin Dunn — "a blue-collar attitude and the Chicago accent to match"[17]

- David Draiman – "distinct Chicago accent"[18]

- Rahm Emanuel – "more refined (if still very Chicago)"[19]

- Siobhan Fallon Hogan

- Dennis Farina — "rich Chicago accent"[20]

- Chris Farley – "beatific Wisconsin accent"[21]

- Dennis Franz — "tough-guy Chicago accent"[22]

- Gerald Ford — "Ford's unremarkable and r-ful accent is from Michigan"[23]

- Susan Hawk — "a Midwestern truck driver whose accent and etiquette epitomized the stereotype of the tacky, abrasive, working-class character"[24]

- Bill Lipinski – "I could live only 100 miles from the gentleman from Illinois (Mr. Lipinski) and he would have an accent and I do not"[25]

- Jim "Mr. Skin" McBride — "a clipped Chicago accent"[26]

- Michael Moore — "a Flintoid, with a nasal, uncosmopolitan accent"[27] and "a recognisable blue-collar Michigan accent"[28]

- Suze Orman — "broad, Midwestern accent"[29]

- Iggy Pop — "plainspoken Midwestern accent"[30]

- Paul Ryan – "may be the first candidate on a major presidential ticket to feature some of the Great Lakes vowels prominently"[31]

- Michael Symon — "Michael Symon's local accent gives him an honest, working-class vibe"[32]

- Lily Tomlin — "Tomlin's Detroit accent"[33]

See also

- List of dialects of the English language

- List of English words from indigenous languages of the Americas

- American English regional differences

- African-American English

- Chicano English

- North Central American English

- Northern cities vowel shift

- Spanglish

References

- ↑ Kortmann, Bernd, Kate Burridge, Rajend Mesthrie, Edgar W. Schneider and Clive Upton (eds) (2004). A Handbook of Varieties of English. Volume 1: Phonology, Volume 2: Morphology and Syntax. Berlin / New York: Mouton de Gruyter. p. xvi.

- ↑ Garn-Nunn, Pamela G.; Lynn, James M. (2004). Calvert's Descriptive Phonetics. Thieme, p. 136.

- ↑ Gordon, Matthew J. (2004). "New York, Philadelphia, and other northern cities: phonology." Kortmann, Bernd, Kate Burridge, Rajend Mesthrie, Edgar W. Schneider and Clive Upton (eds). A Handbook of Varieties of English. Volume 1: Phonology, Volume 2: Morphology and Syntax. Berlin / New York: Mouton de Gruyter. p. 297.

- 1 2 3 Sedivy, Julie (March 28, 2012). "Votes and Vowels: A Changing Accent Shows How Language Parallels Politics". Discover. Retrieved January 24, 2016.

- ↑ Labov, William (2008). "Yankee Cultural Imperialism and the Northern Cities Shift". PowerPoint presentation for paper given at Yale University, October 20, 2008. Online at University of Pennsylvania. Slide 94.

- 1 2 Hillenbrand, James M. (2003). "American English: Southern Michigan". Journal of the International Phonetic Association. 33 (1): 122. doi:10.1017/S0025100303001221.

- ↑ Labov et al., Chapter 14, p. 189.

- ↑ Labov et al., p. 61.

- ↑ Herold, Ruth (1990). "Mechanisms of Merger: The Implementation and Distribution of the Low Back Merger in Eastern Pennsylvania." Ph.D. diss., Univ. of Pennsylvania.

- ↑ Labov et al. (2006), pp. 203-204.

- ↑ Labov et al. (2006), pp. 161.

- ↑ Labov et al. (2006), p. 187

- ↑ van den Doel, Rias (2006). How Friendly Are the Natives? An Evaluation of Native-Speaker Judgements of Foreign-Accented British and American English (PDF). Landelijke onderzoekschool taalwetenschap (Netherlands Graduate School of Linguistics). pp. 268–269.

- ↑ Chozick, Amy (December 28, 2015). "How Hillary Clinton Went Undercover to Examine Race in Education". The New York Times. Retrieved February 2, 2016.

- ↑ Gostin, Nick (2011). "Joan Cusack on 'Mars Needs Moms,' Raising Kids and Her Famous Brother". Parentdish (AOL Inc.)republished at http://www.childcarequest.com/Parent-Dish/joan-cusack-on-mars-needs-moms-raising-kids-and-her-famous-brother.html

- ↑ Stein, Anne (2003). "The über-mayor: what's behind Daley's longevity". Christian Science Monitor.

- ↑ Wawzenek, Bryan. "10 Actors Who Always Show Up on the Best TV Shows." Diffuser.

- ↑ "Disturbed? not if you're David Draiman". Today. June 15, 2006. Retrieved April 5, 2016.

- ↑ Moser, Whet (March 29, 2012). "Where the Chicago Accent Comes From and How Politics is Changing It". Chicago Mag. Retrieved December 27, 2015.

- ↑ Dennis Farina, 'Law & Order' actor, dies at 69. NBC News. 2013.

- ↑ Desowitz, Bill (October 16, 2009). "'Fantastic Mr. Fox' Goes to London". Animation World Network. Retrieved January 7, 2016.

- ↑ "Dennis Franz". Encyclopædia Brittanica. 2014.

- ↑ Metcalf, Allan (2004). Presidential Voices: Speaking Styles from George Washington to George W. Bush. Houghton Mifflin Harcourt. p. 156.

- ↑ Media Literacy: A Reader. Peter Lang. 2007. p. 55.

- ↑ Congressional Record, V. 150, Pt. 17, October 9 to November 17, 2004

- ↑ Brooks, Jake (2004). "Mr. Skin Invades Sundance". The New York Observer. Observer Media.

- ↑ McClelland, Edward (2013). Nothin' but Blue Skies. Bloomsbury Publishing USA. p. 85.

- ↑ "Bush fears Moore because he speaks to the heart of America". The Independent (UK). 2004.

- ↑ Dominus, Susan (2009). "Suze Orman Is Having a Moment". The New York Times.

- ↑ AFP (October 14, 2014). "Iggy Pop's advice for young rockers". Sydney Morning Herald. Retrieved April 1, 2016.

- ↑ Landers, Peter (October 11, 2012). "Paul Ryan Sounds Radical to Linguists". The Wall Street Journal. Retrieved January 24, 2016.

- ↑ "Michael Symon: 2007 winner of 'The Next Iron Chef'". Chicago Tribune. 2015.

- ↑ Maupin, Elizabeth (1997). "'Signs': Still Briming With Intelligent Life." Orlando Sentinel.

Sources

- Labov, William, Sharon Ash, and Charles Boberg (2006). The Atlas of North American English. Berlin: Mouton de Gruyter. ISBN 3-11-016746-8

External links

- Chicago Dialect Samples

- The Guide to Buffalo English

- The Northern Cities Vowel Shift

- NPR interview with Professor William Labov about the shift

- PBS resource from the show "Do you Speak American?"

- Select Annotated Bibliography On the Speech of Buffalo, NY

- Telsur Project Maps