South African English

| Part of a series on the |

| Culture of South Africa |

|---|

|

| History |

| People |

| Cuisine |

|

Festivals |

| Religion |

| Art |

|

Music and performing arts |

| Sport |

|

Monuments |

|

|

0–20%

20–40%

40–60% |

60–80%

80–100% |

|

<1 /km²

1–3 /km²

3–10 /km²

10–30 /km²

30–100 /km² |

100–300 /km²

300–1000 /km²

1000–3000 /km²

>3000 /km² |

South African English (SAfrE, SAfrEng, SAE, en-ZA[1]) is the set of English dialects spoken by South Africans. There is considerable social and regional variation within South African English. Three variants (termed "The Great Trichotomy" by Roger Lass)[2] are commonly identified within White South African English (as in Australian English), spoken primarily by White South Africans: "Cultivated", closely approximating England's standard Received Pronunciation and associated with the upper class; "General", a social indicator of the middle class; and "Broad", associated with the working class, and closely approximating the second-language Afrikaner variety called Afrikaans English. At least two sociolinguistic variants have been definitively studied on a post-creole continuum for the second-language Black South African English spoken by most Black South Africans: a high-end, prestigious "acrolect" and a more middle-ranging, mainstream "mesolect". Other varieties of South African English include Cape Flats English, originally associated with inner-city Cape Coloured speakers, and the Indian South African English of Indian South Africans. Further offshoots include the first-language English varieties spoken by Zimbabweans, Zambians, Swazilanders and Namibians.

Pronunciation

Like English in southern England, such as London, South African English is non-rhotic (except for some Afrikaans-influenced speakers, see below) and features the trap–bath split.

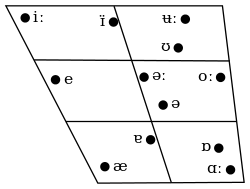

The two main phonological indicators of South African English are the behaviour of the vowels in kit and bath. The kit vowel tends to be "split" so that there is a clear allophonic variation between the close, front [ɪ] and a somewhat more central [ɪ̈]. The bath vowel is characteristically open and back in the General and Broad varieties of SAE. The tendency to monophthongise both /aʊ/ and /aɪ/ to [ɑː] and [aː] respectively, are also typical features of General and Broad SAE.

Features involving consonants include the tendency for voiceless plosives to be unaspirated in stressed word-initial environments, [tj] tune and [dj] dune tend to be realised as [tʃ] and [dʒ] respectively (See Yod coalescence), and /h/ has a strong tendency to be voiced initially.

Vowels

/ɪ/ (the KIT vowel)

- In General and Broad, this vowel is allophonically split between a more front realization ([ɪ] in General, [i] in Broad) and a more central realization ([ɪ̈] in General, [ə] in Broad). More front allophones are used in contact with velar and palatal consonants, whereas more central realizations are used in other environments, with an even more retracted [ɯ̈] being possible before the velarised allophone of /l/. The Cultivated variety lacks this split, and uses a lax front [ɪ] in every position.[4]

- Black mesolect realizes it [i], whereas in the Black acrolect, the quality varies between [ɪ] and [i].[5]

/i/ (the HAPPY vowel)

- It is realized as half-long [iˑ] in White varieties, which is their indicator. Syllables with this vowel may be either unstressed or secondarily stressed.[6]

- Black mesolect realizes it as [ɪ], whereas in the Black acrolect, the quality varies between [ɪ] and [i].[5]

/iː/ (the FLEECE vowel)

- It is realized as [iː] in all White varieties.[7]

- In Black mesolect, the quality is also [i], whereas in Black acrolect, the quality varies between [i] and [ɪ].[5]

/ʊ/ (the FOOT vowel)

- It is realized as a weakly rounded [ʊ̜] in White varieties. Broad speakers may pronounce it as more rounded [ʊ̹], but that is more common in Afrikaans English.[7]

- Black mesolect realizes it as [u], whereas in Black acrolect, the quality varies between [ʊ] and [u].[5]

/uː/ (the GOOSE vowel)

- It is usually central [ʉː] or somewhat fronter in White varieties, though in the Cultivated variety, it is closer to [uː]. Younger (particularly female) speakers of the General variety use an even more front vowel [yː].[7]

- Black mesolect realizes it as [u], whereas in Black acrolect, the quality varies between [ʊ] and [u].[5]

/e/ (the DRESS vowel)

- It is usually close-mid [e] in Cultivated and General varieties, sometimes even higher [e̝ ~ ɪ] in General and Broad. In Broad, it's usually open-mid [ɛ] in Broad speakers, with a potential [æ] allophone before the velarised allophone of /l/.[8]

- Black SAE (both mesolect and acrolect) realizes it as [ɛ].[5]

/ə/ (the COMMA vowel)

- It is realized as [ə] in General and Broad, and varies between [ə] and [ɐ] in Cultivated and Broad varieties close to Afrikaans English.[6]

- Black mesolect realizes it as [ɑ̈], whereas the Black acrolect realizes it as [ə].[5]

/ər/ (the LETTER vowel)

- It is realized as [ə] in White varieties.[6]

- Black mesolect realizes it as [ɑ̈], whereas the Black acrolect realizes it as [ə].[5]

/ɜː/ (the NURSE vowel)

- It is realized as a close-mid rounded vowel, either front [øː] or somewhat more central [ø̈ː] in General and Broad. In the Cultivated variety it is realized as [əː], the same as in RP.[7]

- Black mesolect realizes it as [ɛ], whereas in Black acrolect, the quality varies between [ɜ], [ə] and [ɛ].[5]

/ɔː/ (the THOUGHT vowel)

- It is realized as a close-mid back rounded vowel [oː] in General and Broad varieties, whereas in the Cultivated variety, it is realized as mid [ɔ̝ː], the same as in RP.[9]

- Black SAE (both mesolect and acrolect) realizes it as [ɔ].[5]

/æ/ (the TRAP vowel)

- In Cultivated and General varieties, it is realized as a sound between [æ] and [ɛ], i.e. [æ̝], but Broad speakers often raise it to [ɛ], which can merge with the Broad realization of /e/.[7] However, [a] seems to be the new prestige value in younger Johannesburg (specifically in the Northern Suburbs) speakers of General SAE.[10]

- Black mesolect realizes it as [ɛ], whereas in Black acrolect, the quality varies between [ɛ] and [æ].[5]

/ʌ/ (the STRUT vowel)

- It is realized as an open-to-mid central unrounded vowel [ä ~ ɐ] in White SAE.[7]

- Black mesolect realizes it as [ɑ̈], whereas in Black acrolect, the quality varies between [ʌ] and [ɑ̈].[5]

/ɑː/ (the BATH vowel)

- In the General variety, it is a fully back open unrounded vowel [ɑː]. In the Cultivated variety, it is somewhat more central [ɑ̟ː] whereas in Broad, the tendency is to realize a shortened, rounded and raised vowel [ɒ ~ ɔ].[7]

- Black mesolect realizes it as [ɑ̈], whereas in Black acrolect, the quality varies between [ɑ̈] and [ʌ].[5]

/ɒ/ (the LOT vowel)

- It is realized as a back vowel, either a centralized open rounded [ɒ̈] or an open-mid rounded [ɔ]. Younger General speakers in Cape Town and Natal tend to use an unrounded centralized open-mid [ʌ̈].[7]

- Black mesolect realizes it as [ɔ], whereas in Black acrolect, the quality varies between [ɔ] and [ɒ].[5]

/ɪə/ (the NEAR vowel)

- It is realized as [ɪə] in White varieties, but Broad speakers tend to monophthongize it to [ɪː], especially after /ɪ/.[12]

- Black SAE (both mesolect and acrolect) realizes it as [e].[5]

/ʊə/ (the CURE vowel)

- It is realized as [ʊə] in the Cultivated variety, whereas in Broad it is monophthongized to [oː]. The General variety varies between these two, with a growing tendency to use the monophthong [oː] (the same as the THOUGHT vowel or somewhat lower), especially when /ɪ/ doesn't precede.[13]

- Black mesolect realizes it as [o].[14]

/eə/ (the SQUARE vowel)

- It is realized as [ɛə] in the Cultivated variety, monophthongized to [ɛː] in Broad and monophthongized and raised to [eː] in General.[12]

- Black mesolect realizes it as [ɛ], whereas in Black acrolect, the quality varies between [ɛ] and [e].[5]

/eɪ/ (the FACE vowel)

- It is realized as [eɪ] in General and Cultivated, with opener variants [ɛɪ ~ æɪ] being possible in accents closer to Broad SAE. In Broad SAE, the first element is back [ʌɪ].[12]

- In Black mesolect, the quality varies between [ɛɪ], [eɪ] and [ɛ], whereas in Black acrolect, the quality varies between [e] and [ɛɪ].[5]

/əʊ/ (the GOAT vowel)

- This vowel regularly has a rather front onset in Cultivated and General varieties. In Cultivated, it is realized as [ɛʊ ~ œʊ], with the former being more common. In General, the onset is always rounded, and the offset is central [œʉ̞ ~ œɨ̞], with a tendency to monophthongize it to [œː]. The Broad realization is back [ʌʊ].[12]

- In Black mesolect, the quality varies between [ɔ] and [ɔʊ], whereas in Black acrolect, the quality varies between [o], [ɔ] and [əʊ].[5]

/ɔɪ/ (the CHOICE vowel)

- It is realized as [ɔɪ] in all White varieties. In the Cultivated variety, the first element may be lowered to [ɒ].[12]

- Black SAE (both mesolect and acrolect) realizes it as [ɔɪ].[5]

/aɪ/ (the PRICE vowel)

- It is realized as a diphthong [aɪ] in Cultivated. In General and Broad, it's more often a monophthong [aː], with a diphthong with a retracted onset [ɑ̽ɪ] also possible in Broad.[12]

- Black mesolect realizes it as [ʌɪ], whereas in Black acrolect, the quality varies between [ʌɪ] and [ʌ].[5]

/aʊ/ (the MOUTH vowel)

- It is realized as [ɑ̈ʊ] in Cultivated, [ɑː] in General and [æʊ] in Broad.[12]

- In Black mesolect, the quality varies between [ɔʊ] and [o], whereas in Black acrolect, the quality varies between [aʊ] and [ɔ].[5]

Consonants

Plosives

The plosive phonemes of South African English are /p, b, t, d, k, ɡ/.

- Voicing of the plosives is contrastive in South African English.[6]

- In Broad White South African English, voiceless plosives tend to be unaspirated in all positions, which serves as a marker of this subvariety.[6][15] This is usually thought to be an Afrikaans influence.[15]

- General and Cultivated varieties aspirate /p, t, k/ before a stressed syllable, unless they are followed by an /s/ within the same syllable.[6][15]

- /t, d/ are normally alveolar.[15] In the Broad variety, they tend to be dental [t̪, d̪].[6][15] This pronunciation also occurs in older speakers of the Jewish subvariety of Cultivated SAE.[15]

Fricatives and affricates

The fricative and affricate phonemes of South African English are /f, v, θ, ð, s, z, ʃ, ʒ, x, h, tʃ, dʒ/.

- /x/ occurs only in words borrowed from Afrikaans and Khoisan, such as gogga /ˈxɒxə/ 'insect'. Many speakers realize /x/ as uvular [χ], a sound which is more common in Afrikaans.[6]

- /θ/ may be realized as [f] in Broad varieties (see Th-fronting), but it is more accurate to say that it is a feature of Afrikaans English.[6][15] This is especially common word-finally.[15]

- /v, ð, z, ʒ/ in word-final position tend to be voiceless. They contrast with /f, θ, s, ʃ/ by the presence or lack of pre-fortis clipping.[6]

- In Indian variety, the labiodental fricatives /f, v/ are realized without audible friction, i.e. as approximants [ʋ̥, ʋ].[16]

- In General and Cultivated varieties, intervocalic /h/ (as in ahead) may be voiced [f].[17]

- There is not a full agreement about the voicing of /h/ in Broad varieties:

- Lass (2002) states that:

- Voiced [f] is the normal realization of /h/ in Broad varieties.[17]

- It is often deleted, e.g. in word-initial stressed syllables (as in house), but at least as often, it is pronounced even if it seems deleted. The vowel that follows the [ɦ] allophone in the word-initial syllable often carries a low or low rising tone, which, in rapid speech, can be the only trace of the deleted /h/. That creates potentially minimal tonal pairs like oh (neutral [ʌʊ˧] or high falling [ʌʊ˦˥˩]) vs. hoe (low [ʌʊ˨] or low rising [ʌʊ˩˨]).[17]

- Bowerman (2004) states that in Broad varieties close to Afrikaans English, /h/ is voiced [f] before a stressed vowel.[6]

- Lass (2002) states that:

Sonorants

The sonorant phonemes of South African English are /m, (hw), w, n, l, r, j, ŋ/.

- General and Broad varieties have a wine–whine merger. but some speakers of Cultivated SAE (particularly the elderly) still distinguish /hw/ from /w/.[18][19]

- /n/ is normally alveolar, but it has an optional dental allophone [n̪] before dental consonants.[15][18]

- /l/ has two allophones:

- Clear (neutral or somewhat palatalised)[19] [l] in syllable-initial position;[18][19]

- Velarised [lˠ] (or uvularised [lʶ])[19] in syllable-final position.[18][19]

- One source states that the dark /l/ has a "hollow pharyngealised" quality [lˤ],[11] rather than velarised or uvularised.

- In Cultivated and General varieties, /r/ is an approximant, usually postalveolar or (less commonly)[15] retroflex.[15][18] In emphatic speech, Cultivated speakers may realize /r/ as a (often long) trill [r].[19] Older speakers of the Cultivated variety may realize intervocalic /r/ as a tap [ɾ], a feature which is becoming increasingly rare.[19]

- Broad SAE realizes /r/ as a tap [ɾ], sometimes even as a trill [r] - a pronunciation which is at times stigmatised as a marker of this variety.[18][19] The trill [r] is more commonly considered a feature of the second language Afrikaans English variety.[18][19]

- Another possible realization of /r/ is uvular trill [ʀ], which has been reported to occur in the Cape Flats dialect.[20]

- South African English is non-rhotic, except for some Broad varieties spoken in the Cape Province (typically in -er suffixes, as in writer). It appears that postvocalic /r/ is entering the speech of younger people under the influence of American English.[18][19]

- Linking /r/ (as in for a while) is used only by some speakers.[18]

- There is not a full agreement about intrusive /r/ (as in law and order) in South African English:

- Lass (2002) states that it is rare, and some speakers with linking /r/ never use the intrusive /r/.[17]

- Bowerman (2004) states that it is absent from this variety.[18]

- In contexts where many British and Australian accents use the intrusive /r/, speakers of South African English who do not use the intrusive /r/ create an intervocalic hiatus. Phonetically, it can be realized in three ways:[18]

- Vowel deletion: [loːnoːdə];[18]

- Adding a semivowel corresponding to the preceding vowel: [loːwənoːdə];[18]

- Inserting a glottal stop: [loːʔənoːdə]. This is typical of Broad varieties.[18]

- Before a high front vowel, /ɪ/ is foritified to [ɣ] in Broad and some of the General varieties.[18]

Vocabulary

There are words that do not exist in British or American English, usually derived from languages of Africa such as Afrikaans or Zulu, although, particularly in Durban, there is also an influence from Indian languages and slang developed by subcultures, particularly surfers. Terms in common with North American English include 'mom' (most British and Australian English: mum), 'freeway' or 'highway' (British English 'motorway'), 'cellphone' (British and Australian English: mobile), and 'buck' meaning money (rand, in this case, not a dollar).

One of the most noticeable traits of South African English-speakers is the strong tendency to use the Afrikaans 'ja' [='yes'] in any situation where other English-speakers would say 'yes', 'yeah' or 'Well, ...'. The parallel is extended to the expression 'ja-nee' [literally, 'yes-no'; indicating a partial agreement or acknowledgement of a point] which becomes 'Ja, no, ...'. Such usage is widely acceptable, although it is understood to be incorrect English and would not be used in strictly formal contexts, such as in court or in a job interview.

South Africans are also known for their irregular use of the word 'now'. Particularly, 'just now' is taken to mean 'in a while' or 'later' (up to a few hours' time) rather than 'this very minute', for which a South African would say 'right now'. 'Now now' is relatively more immediate, implying a delay of a few minutes to around half an hour. The word 'just' also has a looser meaning than in British English when applied to location; expressions such as 'just there', or 'just around the corner' are not taken to imply a precise point.

Another expression is to 'come with', as in 'are they coming with?'[21] This is influenced by the Afrikaans phrase hulle kom saam, literally 'they come together', with saam being misinterpreted as 'with'.[22] In Afrikaans, saamkom is a separable verb, similar to meekomen in Dutch and mitkommen in German, which is translated into English as 'to come along'.[23] 'Come with?' is also encountered in areas of the Upper Midwest of the United States, which had a large number of Scandinavian, Dutch and German immigrants, who, when speaking English, translated equivalent phrases directly from their own languages.[24]

Some words peculiar to South African English include 'takkies', 'tackie' or 'tekkie' for sneakers (American) or trainers (British), 'combi' or 'kombi' for a small van similar to a Volkswagen Kombi, 'bakkie' for a pick-up truck, 'kiff' for pleasurable, 'lekker' for nice, 'donga' for gully, 'robot' for a traffic light, 'dagga' for cannabis, 'braai' for barbecue and 'jol' for party. South Africans generally refer to the different codes of football, such as soccer and rugby, by those names.

There is some difference between South African English dialects: in Johannesburg the local form is very strongly English-based, while its Eastern Cape counterpart has a strong Afrikaans influence. Although differences between the two are sizeable, there are many similarities.

Contributions to English worldwide

Several South African words, usually from Afrikaans or other indigenous languages of the region, have entered world English: those relating to human activity include apartheid; commando and trek and those relating to indigenous flora and fauna include veld; vlei; spoor; aardvark; impala; mamba; boomslang; meerkat and wildebeest.

Recent films such as District 9 have also brought South African and Southern African English to a global audience, as have television personalities like Die Antwoord, Austin Stevens and Trevor Noah.

Large numbers of the British diaspora and other South African English speakers now live in Australia, Britain, Canada, New Zealand and some Persian Gulf states and may have influenced their host community's dialects to some degree. South African English and its slang also has a substantial presence in neighbouring countries like Namibia, Zimbabwe, Botswana and Zambia. English accents vary considerably depending on region and local ethnic influences.

Demographics

The South African National Census of 2011 found a total of 4,892,623 speakers of English as a first language,[25]:23 making up 9.6% of the national population.[25]:25 The provinces with significant English-speaking populations were the Western Cape (20.2% of the provincial population), Gauteng (13.3%) and KwaZulu-Natal (13.2%).[25]:25

English was spoken across all ethnic groups in South Africa. The breakdown of English-speakers according to the conventional racial classifications used by Statistics South Africa is described in the following table.

| Population group | English-speakers[25]:26 | % of population group[25]:27 | % of total English-speakers |

|---|---|---|---|

| Black African | 1,167,913 | 2.9 | 23.9 |

| Coloured | 945,847 | 20.8 | 19.3 |

| Indian or Asian | 1,094,317 | 86.1 | 22.4 |

| White | 1,603,575 | 35.9 | 32.8 |

| Other | 80,971 | 29.5 | 1.7 |

| Total | 4,892,623 | 9.6 | 100.0 |

English Academy of Southern Africa

The English Academy of Southern Africa (EASA) has no official connection with the government and can only attempt to advise, educate, encourage, and discourage. It was founded in 1961 by Professor Gwen Knowles-Williams of the University of Pretoria in part to defend the role of English against pressure from supporters of Afrikaans. It encourages scholarship in issues surrounding English in Africa through regular conferences.

In July 2010, the English Academy of Southern Africa launched an online magazine, Teaching English Today, for academic discussion related to English and teaching English as a subject in schools.

Examples of South African accents

The following examples of South African accents were obtained from George Mason University:

- Native English: Male (Cape Town, South Africa)

- Native English: Female (Cape Town, South Africa)

- Native English: Male (Port Elizabeth, South Africa)

- Native English: Male (Nigel, South Africa)

See also

- List of English words of Afrikaans origin

- List of lexical differences in South African English

- List of South African slang words

- Standard written English

- Regional accents of English

References

- ↑

en-ZAis the language code for South African English, as defined by ISO standards (see ISO 639-1 and ISO 3166-1 alpha-2) and Internet standards (see IETF language tag). - ↑ Lass (2002), p. 109.

- ↑ "Rodrik Wade, MA Thesis, Ch 4: Structural characteristics of Zulu English". Archived from the original on 17 May 2008. Some symbols were changed to better reflect the actual pronunciation.

- ↑ Bowerman (2004), p. 936.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 19 20 21 Van Rooy (2004), pp. 945 and 947.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 Bowerman (2004), p. 939.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 Bowerman (2004), p. 937.

- ↑ Bowerman (2004), pp. 936–937.

- ↑ Bowerman (2004), pp. 937–938.

- ↑ Bekker (2008:83–84) "More recently, Bekker and Eley (2007) conducted an acoustic analysis of the monophthongs of GenSAE, using data elicited from two sets of subjects: young females from private schools in Johannesburg and young females from public schools in East London. Results suggest that a lowered TRAP vowel is a new prestige value, particularly for the Johannesburg area, and more specifically for one of the more wealthy areas of Johannesburg; the so-called ‘Northern Suburbs’ (...)."

- 1 2 3 Collins & Mees (2013), p. 194.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 Bowerman (2004), p. 938.

- ↑ Bowerman (2004), pp. 938–939.

- ↑ Van Rooy (2004), p. 945.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 Lass (2002), p. 120.

- ↑ Mesthrie (2004), p. 960.

- 1 2 3 4 Lass (2002), p. 122.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 Bowerman (2004), p. 940.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 Lass (2002), p. 121.

- ↑ Finn (2004), p. 976.

- ↑ Africa, South and Southeast Asia, Rajend Mesthrie, Mouton de Gruyter, 2008, page 475

- ↑ A handbook of varieties of English: a multimedia reference tool. Morphology and syntax, Volume 2, Bernd Kortmann, Mouton de Gruyter, 2004, page 951

- ↑ Pharos Tweetalige skoolwoordeboek/Pharos Bilingual school dictionary, Pharos Dictionaries, Pharos, 2014

- ↑ What's with 'come with'?, Chicago Tribune, December 8, 2010

- 1 2 3 4 5 Census 2011: Census in brief (PDF). Pretoria: Statistics South Africa. 2012. ISBN 9780621413885.

Bibliography

- Bekker, Ian (2008). The vowels of South African English (PDF) (Ph.D.). North-West University, Potchefstroom.

- Bowerman, Sean (2004), "White South African English: phonology", in Schneider, Edgar W.; Burridge, Kate; Kortmann, Bernd; Mesthrie, Rajend; Upton, Clive, A handbook of varieties of English, 1: Phonology, Mouton de Gruyter, pp. 931–942, ISBN 3-11-017532-0

- Collins, Beverley; Mees, Inger M. (2013) [First published 2003], Practical Phonetics and Phonology: A Resource Book for Students (3rd ed.), Routledge, ISBN 978-0-415-50650-2

- de Gruyter, Walter (2008). Africa, South and Southeast Asia (Ph.D.).

- Finn, Peter (2004), "Cape Flats English: phonology", in Schneider, Edgar W.; Burridge, Kate; Kortmann, Bernd; Mesthrie, Rajend; Upton, Clive, A handbook of varieties of English, 1: Phonology, Mouton de Gruyter, pp. 934–984, ISBN 3-11-017532-0

- Lanham, Len W. (1967), The pronunciation of South African English, Cape Town: Balkema

- Lass, Roger (2002), "South African English", in Mesthrie, Rajend, Language in South Africa, Cambridge University Press, ISBN 9780521791052

- Mesthrie, Rajend (2004), "Indian South African English: phonology", in Schneider, Edgar W.; Burridge, Kate; Kortmann, Bernd; Mesthrie, Rajend; Upton, Clive, A handbook of varieties of English, 1: Phonology, Mouton de Gruyter, pp. 953–963, ISBN 3-11-017532-0

- Mott, Brian (2012), "Traditional Cockney and popular London speech", Dialectologia, RACO (Revistes Catalanes amb Accés Obert), 9: 69–94, ISSN 2013-2247

- van Rooy, Bertus (2004), "Black South African English: phonology", in Schneider, Edgar W.; Burridge, Kate; Kortmann, Bernd; Mesthrie, Rajend; Upton, Clive, A handbook of varieties of English, 1: Phonology, Mouton de Gruyter, pp. 943–952, ISBN 3-11-017532-0

Further reading

- Bekker, Ian (2012), "The story of South African English: A brief linguistic overview", International Journal of Language, Translation and Intercultural Communication, 1, doi:10.12681/ijltic.16

- Bosch, Barbara; De Klerk, Vivian (1996), "Language Attitudes and their Implications for the Teaching of English in the Eastern Cape", in De Klerk, Vivian, Focus on South Africa, John Benjamins Publishing, ISBN 90-272-4873-7

- Branford, William (1994), "9: English in South Africa", in Burchfield, Robert, The Cambridge History of the English Language, 5: English in Britain and Overseas: Origins and Development, Cambridge University Press, pp. 430–496, ISBN 0-521-26478-2

- Branford, William (1996), "English in South African society: a Preliminary Overview", in De Klerk, Vivian, Focus on South Africa, John Benjamins Publishing, ISBN 90-272-4873-7

- Da Silva, Arista B. (2008), South African English: a sociolinguistic investigation of an emerging variety.

- Gough, David (1996), "Black English in South Africa", in De Klerk, Vivian, Focus on South Africa, John Benjamins Publishing, ISBN 90-272-4873-7

- Lanham, Len W. (1979), The Standard in South African English and Its Social History, Heidelberg: Julius Groos Verlag, ISBN 3-87276-210-9

- Lanham, Len W. (1996), "A History of English in South Africa", in De Klerk, Vivian, Focus on South Africa, John Benjamins Publishing, ISBN 90-272-4873-7

- Malan, Karen (1996), "Cape Flats English", in De Klerk, Vivian, Focus on South Africa, John Benjamins Publishing, ISBN 90-272-4873-7

- Mesthrie, Rajend (1996), "Language Contact, Transmission, Shift: South African Indian English", in De Klerk, Vivian, Focus on South Africa, John Benjamins Publishing, ISBN 90-272-4873-7

- Prinsloo, Claude Pierre (2000), A comparative acoustic analysis of the long vowels and diphthongs of Afrikaans and South African English (PDF), Pretoria: University of Pretoria

- Silva, Penny (1996), "Lexicography for South African English", in De Klerk, Vivian, Focus on South Africa, John Benjamins Publishing, ISBN 90-272-4873-7

- Titlestad, Peter (1996), "English, the Constitution and South Africa's Language Future", in De Klerk, Vivian, Focus on South Africa, John Benjamins Publishing, ISBN 90-272-4873-7

- Watermeyer, Susan (1996), "Afrikaans English", in De Klerk, Vivian, Focus on South Africa, John Benjamins Publishing, ISBN 90-272-4873-7

- Webb, Victor (1996), "English and Language Planning for South Africa: the Flip Side", in De Klerk, Vivian, Focus on South Africa, John Benjamins Publishing, ISBN 90-272-4873-7

- Wells, John C. (1982), "8.3 South Africa", Accents of English 3: Beyond The British Isles, Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, pp. 610–622, ISBN 0-521-28541-0

- Wright, Lawrence (1996), "The Standardisation Question in Black South African English", in De Klerk, Vivian, Focus on South Africa, John Benjamins Publishing, ISBN 90-272-4873-7

External links

- English Academy of South Africa

- Picard, Brig (Dr) J. H, SM, MM. "English for the South African Armed Forces" at the Wayback Machine (archived 22 June 2008)

- Zimbabwean Slang Dictionary

- "Surfrikan", South African surfing slang

- The influence of Afrikaans on SA English (in Dutch)

- The Expat Portal RSA Slang

- Several Samples of The Dialect

Countries.png)