Iranian Georgians

| Total population | |

|---|---|

| (100,000 + [1]) | |

| Regions with significant populations | |

| Fereydan, Gilan, Mazandaran, Golestan, Isfahan, Fars, Khorasan, Tehran | |

| Languages | |

| Persian, Georgian, Mazandarani | |

| Religion | |

| Shi'a Islam[1] | |

| Related ethnic groups | |

| Georgians, people of Iran |

Iranian Georgians (Georgian: ირანის ქართველები) are Iranian citizens who are ethnically Georgian, and are an ethnic group living in Iran. Today's Georgia was a subject to Iran from the 16th century till the early 19th century, starting with the Safavids in power. Shah Abbas I, his predecessors, and successors, relocated by force hundreds of thousands of Christian, and Jewish Georgians as part of his programs to reduce the power of the Qizilbash, develop industrial economy, strengthen the military, and populate newly built towns in various places in Iran including the provinces of Isfahan and Mazandaran.[2] A certain amount consisting of nobles also migrated voluntarily over the centuries,[3] as well as some that moved as muhajirs in the 19th century to Iran, following the Russian conquest of the Caucasus.[4] The Georgian community of Fereydunshahr have retained their distinct Georgian identity until this day, while had to adopt aspects of Iranian culture such as Persian language, and Twelver Shia Islam in order to survive in the society.[5][6][7]

History

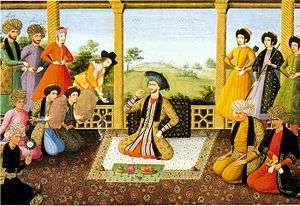

.jpg)

Safavid era

Most likely, the first extant community of Georgians within Iran was formed following Shah Tahmasp I's invasions of Georgia and the rest of the Caucasus, in which he deported some 30,000 Georgians and other Caucasians back to mainland Safavid Iran.[8][9] The first genuine compact Georgian settlements however appeared in Iran in the 1610s when Shah Abbas I relocated some two hundred thousand from their historical homeland, eastern Georgian provinces of Kakheti and Kartli, following a punitive campaign he conducted against his formerly most loyal Georgian servants, namely Teimuraz I of Kakheti and Luarsab II of Kartli.[10] Most of modern-day Iranian Georgians are the latters' descendants,[1] although the first large movements of Georgians from the Caucasus to the heartland of the Safavid empire in Iran happened as early as during the rule of Tahmasp I.[11] Subsequent waves of large deportations after Abbas also occurred throughout the rest of the 17th, but also the 18th and 19th centuries, the last ones by the Qajar Dynasty. A certain amount also migrated as muhajirs in the 19th century to Iran, following the Russian conquest of the Caucasus. The Georgian deportees were settled by the Shah's government into the scarcely populated lands which were quickly made by their new inhabitants into the lively agricultural areas. Many of these new settlements were given Georgian names, reflecting the toponyms found in Georgia. During the Safavid era, Georgia became so politically and somewhat culturally intertwined with Iran that Georgians replaced the Qizilbash among the Safavid officials, alongside the Circassians and Armenians.

During his travels the Italian adventurer Pietro Della Valle claimed that there was no household in Persia without its Georgian slaves, noticing the huge amounts of Georgians present everywhere in society.[12] The later Safavid capital, Isfahan, was home to many Georgians. Many of the city’s inhabitants were of Georgian, Circassian, and Daghistani descent.[13] Engelbert Kaempfer, who was in Safavid Persia in 1684-85, estimated their number at 20,000.[13][14] Following an agreement between Shah Abbas I and his Georgian subject Teimuraz I of Kakheti ("Tahmuras Khan"), whereby the latter submitted to Safavid rule in exchange for being allowed to rule as the region’s wāli (governor) and for having his son serve as dāruḡa ("prefect") of Isfahan in perpetuity, a Georgian prince converted to Islam served as governor.[13] He was accompanied by a certain number of soldiers, and they spoke in Georgian among themselves.[13] There must also have been some Georgian Orthodox Christians.[13] The royal court in Isfahan had a great number of Georgian ḡolāms (military slaves) as well as Georgian women.[13] Although they spoke Persian or Turkic, their mother tongue was Georgian.[13]

During the last days of the Safavid empire, the Safavids arch enemy, namely the neighboring Ottoman Turks, as well as neighboring Imperial Russia, but also the tribal Afghans from the far off easternmost regions of the empire took advantage of Iranian internal weakness and invaded Iran. The Iranian Georgian contribution in wars against the invading Afghans was crucial. Georgians fought in the battle of Golnabad, and in the battle of Fereydunshahr. In the latter battle they brought a humiliating defeat to the Afghan army.

In total, the Persian sources mention that during the Safavid era 225,000 Georgians were transplanted to mainland Iran during the first two centuries, while the Georgian sources keep this number at 245,000.[15]

Afsharid era

During the Afsharid dynasty, 5,000 Georgian families were moved to mainland Iran according to the Persian sources,[15] while the Georgian sources keep it on 30,000 persons.[15]

Qajar era

During the Qajar dynasty, the last Iranian empire that would, despite very briefly, have effective control over Georgia, 15,000 Georgians were moved to Iran according to the Persian sources, while the Georgian ones mention 22,000 persons.[15] This last large wave of Georgian movement and settlement towards mainland Iran happened as a result of the Battle of Krtsanisi in 1795.

Modern Iran

Despite their isolation from Georgia, many Georgians have preserved their language and some traditions, but embraced Islam. The ethnographer Lado Aghniashvili was first from Georgia to visit this community in 1890.

In the aftermath of World War I, the Georgian minority in Iran was caught in the pressures of the rising Cold War. In 1945, this compact ethnic community, along with other ethnic minorities that populated northern Iran, came to the attention of the Soviet as a possible instrument for fomenting unrest in Iranian domestic politics. While the Soviet Georgian leadership wanted to repatriate them to Georgia, Moscow clearly preferred to keep them in Iran. The Soviet plans were abandoned only after Joseph Stalin realized that his plans to obtain influence in northern Iran foiled by both Iranian stubbornness and United States pressure.[16]

In June 2004, the new Georgian president, Mikheil Saakashvili, became the first Georgian politician to have visited the Iranian Georgian community in Fereydunshahr. Thousands of local Georgians gave the delegation a warm welcome, which included waving of the newly adopted Georgian national flag with its five crosses.[17][18] Saakashvili who stressed that the Iranian Georgians have historically played an important role in defending Iran put flowers on the graves of the Iranian Georgian dead of the eight years long Iran–Iraq War.[19]

Notable Georgians of Iran

Many Iranian military commanders and administrators were (Islamized) Georgians.[20] Many members of the Safavid and Qajar dynasties and nobility had Georgian blood.[21][22] In fact, the heavily mixed Safavid dynasty (1501-1736) was of partial Georgian origins from its very beginning.

List of Iranian Georgians

Military: Allahverdi Khan, Otar Beg Orbeliani, Rustam Khan the sipahsalar, Imam-Quli Khan, Yusef Khan-e Gorji, Grigor Mikeladze, Konstantin Mikeladze, Daud Khan Undiladze, Rustam Khan the qullar-aqasi, Eskandar Mirza (d. 1711), Bektash of Kakheti, Kaikhosro of Kartli, Shah-Quli Khan (Levan of Kartli), Eskandar Mirza (Prince Aleksandre of Georgia), Prince Rostom of Kartli, Vsevolod Starosselsky

Arts: Aliquli Jabbadar, Antoin Sevruguin, Nima Yooshij, Siyâvash, Ahmad Beg Gorji Aktar (fl. 1819) and his brother Mohammad-Baqer Beg "Nasati”,[23]

Royalty/nobility:[note 1] Bijan Beg Saakadze, Semayun Khan (Simon II of Kartli), Otar Beg Orbeliani, Abd al-Ghaffar Amilakhori, Sohrab I, Duke of Araghvi (Zurab), Pishkinid dynasty, Haydar Mirza Safavi, Safi of Persia, Dowlatshah, Gurgin Khan (George XI of Kartli), Imām Qulī Khān (David II of Kakheti), Bagrat Khan (Bagrat VII), Constantine Khan (Constantine I), Mahmād Qulī Khān (Constantine II of Kakheti), Ivan Aleksandrovich Bagration, Nazar Alī Khān (Heraclius I of Kakheti), 'Isa Khan Gorji (Prince Jesse of Kakheti), Isā Khān (Jesse of Kakheti), Princess Ketevan of Kakheti, Shah-Quli Khan (Levan of Kartli), Manuchar II Jaqeli, Eskandar Mirza (Prince Aleksandre of Georgia), Shah Nawaz (Vakhtang V of Kartli), Mustafa, fourth son of Tahmasp I,[24] Heydar Ali, third son of Tahmasp I.[25]

Academics: Parsadan Gorgijanidze, Jamshid Giunashvili

Politicians/officials: Shahverdi Khan (Georgian), Manouchehr Khan Gorji, Amin al-Sultan, Bahram Aryana, Manucheher Khan Motamed-od-Dowleh, Vakhushti Khan Orbeliani, Ahmad ibn Nizam al-Mulk, Ishaq Beg (Alexander of Kartli, d. 1773), Bijan Beg (son of Rustam Khan the sipahsalar), 'Isa Khan Gorji, Otar Beg Orbeliani,

Others: Undiladze, Mahmoud Karimi Sibaki

The names of actors Cyrus Gorjestani and Sima Gorjestani, as well as the late Nematollah Gorji, suggest that they are/were (at least from the paternal side) of Georgian origin. Reza Shah Pahlavi's mother was a Georgian muhajir,[26][27] who most likely came to mainland Persia after Persia was forced to cede all of its territories in the Caucasus following the Russo-Persian Wars several decades prior to Reza Shah's birth. The Iranian-Australian University Professor, Dr Leila Karimi,[28] born in a Georgian Family (originally known as Goginashvili) in Isfahan.

For a more lengthy discussion on Georgians and Persia refer to.[29]

Geographic distribution, language and culture

The Georgian language is still used by a minority of people in Iran. The center of Georgians in Iran is Fereydunshahr, a small city, 150 km to the west of Isfahan in the area historically known as Fereydan. In this area there are 10 Georgian towns and villages around Fereydunshahr. In this region the old Georgian identity is retained the best compared to other places in Iran, and most people speak and understand the Georgian language there.

There were other compact settlements in Khorasan at Abbas Abad (half-way between Shahrud and Sabzevar where there remained only one old woman who remembered Georgian in 1934), Mazandaran at Behshahr and Farah Abad, Gilan, Isfahan Province at Najafabad, Badrud, Rahmatabad, Yazdanshahr and Amir Abad. These areas are frequently called Gorji Mahalleh ("Georgian neighborhood"). Many Georgians or Iranians of partial Georgian descent are also scattered in major Iranian cities, such as Tehran, Isfahan, Rasht, Karaj and Shiraz. Most of these communities no longer speak the Georgian language, but retain aspects of Georgian culture and keep a Georgian conscious.[30] Some argue that Iranian Georgians retain remnants of Christian traditions, but there is no evidence for this. Most Georgians in Fereydunshahr and Fereydan speak and understand Georgian. Iranian Georgians observe the Shia traditions and also non-religious traditions similar to other people in Iran. They observe the traditions of Nowruz.

The local self-designation of Georgians in Iran, like the rest of the Georgians over the world is Kartveli (Georgian: ქართველი, from Kartvelebi, Georgian: ქართველები, namely Georgians), although occasionally the ethonyms Gorj, Gorji, or even Gurj-i (from Persian "Gorji" which means Georgian). They call their language Kartuli (Georgian: ქართული). As Rezvani states, this is not surprising given that all other Georgian dialects in Iran are extinct.

The number of Georgians in Iran is estimated to be over 100,000. According to Encyclopaedia Georgiana (1986) some 12,000–14,000 lived in rural Fereydan c. 1896,[31] and a more recent estimation cited by Rezvani (published 2009, written in 2008) states that there may be more than 61,000 Georgians in Fereydan.[32] Modern-day estimations regarding the number of Iranian Georgians are that they compose over 100,000, but these numbers are obvious underestimations as it is believed that the modern Iranian Georgians are more than Georgians in Georgia. (3,500,000 +). They are also the largest Caucasus-derived group in the nation, ahead of the Circassians.[33]

See also

- Iran-Georgia relations

- Georgia-Persia relations

- Peoples of the Caucasus in Iran

- Islam in Georgia

- Georgians in Turkey

- Georgian Jews

- Abbas I's Kakhetian and Kartlian campaigns

- List of Georgians

- Circassians in Iran

Notes

- ↑ Most of the nobility and royalty of Georgian descent held numerous functions as officials and/or in the military, but are, for the sake of coherence and simplicity, virtually only included here in the list of "Royalty/nobility".

External links

- Pierre Oberling, Georgian communities in Persia. Encyclopædia Iranica

- (Georgian) Fereydan - Little Georgia

- (Georgian) Georgian Radio of Iran

- Ali Attār, Georgians in Iran, in Persian, Jadid Online, 2008, .

A Slide Show of Georgians in Iran by Ali Attār, Jadid Online, 2008, (5 min 31 sec).

References

- 1 2 3 Rezvani, Babak (Winter 2009). "The Fereydani Georgian Representation". Anthropology of the Middle East. 4 (2): 52–74. doi:10.3167/ame.2009.040205.

- ↑ Matthee, Rudolph P. (1999), The Politics of Trade in Safavid Iran: Silk for Silver, 1600-1730.

- ↑ Roger Savory. Iran Under the Safavids Cambridge University Press, 24 sep. 2007. ISBN 0521042518 p 184

- ↑ "Caucasus Survey". Retrieved 3 May 2015.

- ↑ Muliani, S. (2001) Jaygah-e Gorjiha dar Tarikh va Farhang va Tammadon-e Iran. Esfahan: Yekta [The Georgians’ position in the Iranian history and civilization]

- ↑ Rahimi, M.M. (2001) Gorjiha-ye Iran; Fereydunshahr. Esfahan: Yekta [The Georgians of Iran; Fereydunshahr]

- ↑ Sepiani, M. (1980) Iranian-e Gorji. Esfahan: Arash [Georgian Iranians]

- ↑ Hamilton Alexander Rosskeen Gibb, Bernard Lewis, Johannes Hendrik Kramers, Charles Pellat, Joseph Schacht. The Encyclopaedia of Islam, parts 163-178 (Volume 10). Original from the University of Michigan. p 109

- ↑ "ṬAHMĀSP I". Retrieved 29 October 2015.

- ↑ Mikaberidze 2015, pp. 291, 536.

- ↑ Slaves of the Shah:New Elites of Safavid Iran. 2004. Retrieved 1 April 2014.

- ↑ "Georgians in Safavid Iran". Retrieved 26 April 2014.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 Isfahan-Safavid Period VII

- ↑ Matthee 2012, p. 67.

- 1 2 3 4 Babak Rezvani. Iranian Georgians

- ↑ Svetlana Savranskaya and Vladislav Zubok (editors), Cold War International History Project Bulletin, I issue, 14/15 – Conference Reports, Research Notes and Archival Updates, p. 401. Woodrow Wilson International Center for Scholars. Accessed on September 16, 2007.

- ↑ Sanikidze, George. Walker, Edward W. Islam and Islamic Practices in Georgia Publication Date; 08-01-2004. p 19

- ↑ Mikaberidze 2015, p. 536.

- ↑ http://www.iran-newspaper.com/1383/830420/html/internal.htm

- ↑ Babak Rezvani. "Ethno-territorial conflict and coexistence in the caucasus, Central Asia and Fereydan" Amsterdam University Press, 15 mrt. 2014 ISBN ISBN 978-9048519286 p 171

- ↑ Aptin Khanbaghi (2006)The Fire, the Star and the Cross: Minority Religions in Medieval and Early. London & New YorkIB Tauris. ISBN 1-84511-056-0, pp. 130-1.

- ↑ Babak Rezvani. "Ethno-territorial conflict and coexistence in the caucasus, Central Asia and Fereydan" Amsterdam University Press, 15 mrt. 2014 ISBN 978-9048519286 p 171

- ↑ Khaleghi-Motlagh, DJ (1984). "Aḵtar, Aḥmad Beg Gorjī". Encyclopædia Iranica, Vol. I, Fasc. 7. pp. 730–731. Retrieved 15 February 2015.

- ↑ Juan de Persia, Don Juan of Persia, (Routledge, 2004), 129.

- ↑ Savory, Roger, Iran Under the Safavids, (Cambridge University Press, 2007), 68.

- ↑ "The Life and Times of the Shah". Retrieved 22 April 2015.

- ↑ "The Pahlavi Dynasty: An Entry from Encyclopaedia of the World of Islam". Retrieved 22 April 2015.

- ↑ http://www.latrobe.edu.au/health/about/staff/profile?uname=LKarimi

- ↑ Encyclopædia Iranica on Gorjestan

- ↑ Mikaberidze 2015, p. 291.

- ↑ Encyclopaedia Georgiana (1986), vol. 10, Tbilisi: p. 263.

- ↑ Rezvani, Babak. The Fereydani Georgian Representation of Identity and Narration of History 2009 Journal; Anthropology of the Middle East. Berghahn Journals. Vol 4. No 2. p 52

- ↑ Encyclopedia of the Peoples of Africa and the Middle East Facts On File, Incorporated ISBN 143812676X p 141

Sources

- Matthee, Rudi (2012). Persia in Crisis: Safavid Decline and the Fall of Isfahan. I.B.Tauris. ISBN 978-1845117450.

- Mikaberidze, Alexander (2015). Historical Dictionary of Georgia (2 ed.). Rowman & Littlefield. ISBN 978-1442241466.

- Muliani, S. (2001) Jâygâhe Gorjihâ dar Târix va Farhang va Tamaddone Irân (The Georgians’ Position in Iranian History and Civilization). Esfahan: Yekta Publication. ISBN 978-964-7016-26-1. (Persian)

- Rahimi, M. M. (2001) Gorjihâye Irân: Fereydunšahr (The Georgians of Iran; Fereydunshahr). Esfahan: Yekta Publication. ISBN 978-964-7016-11-7. (Persian)

- Sepiani, M. (1980) Irâniyâne Gorji (Georgian Iranians). Esfahan: Arash Publication. (Persian)

- Rezvani, B. (2008) "The Islamization and Ethnogenesis of the Fereydani Georgians". Nationalities Papers 36 (4): 593-623. doi:10.1080/00905990802230597

- Oberling, Pierre (1963). "Georgians and Circassians in Iran". Studia Caucasica (1): 127-143

- Saakashvili visited Fereydunshahr and put flowers on the graves of the Iranian Georgian martyrs' graves, showing respect towards this community (Persian)