Isotopes of americium

| Actinides and fission products by half-life | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Actinides[1] by decay chain | Half-life range (y) |

Fission products of 235U by yield[2] | ||||||

| 4n | 4n+1 | 4n+2 | 4n+3 | |||||

| 4.5–7% | 0.04–1.25% | <0.001% | ||||||

| 228Ra№ | 4–6 | † | 155Euþ | |||||

| 244Cmƒ | 241Puƒ | 250Cf | 227Ac№ | 10–29 | 90Sr | 85Kr | 113mCdþ | |

| 232Uƒ | 238Puƒ№ | 243Cmƒ | 29–97 | 137Cs | 151Smþ | 121mSn | ||

| 248Bk[3] | 249Cfƒ | 242mAmƒ | 141–351 |

No fission products | ||||

| 241Amƒ | 251Cfƒ[4] | 430–900 | ||||||

| 226Ra№ | 247Bk | 1.3 k – 1.6 k | ||||||

| 240Puƒ№ | 229Th№ | 246Cmƒ | 243Amƒ | 4.7 k – 7.4 k | ||||

| 245Cmƒ | 250Cm | 8.3 k – 8.5 k | ||||||

| 239Puƒ№ | 24.1 k | |||||||

| 230Th№ | 231Pa№ | 32 k – 76 k | ||||||

| 236Npƒ | 233Uƒ№ | 234U№ | 150 k – 250 k | ‡ | 99Tc₡ | 126Sn | ||

| 248Cm | 242Puƒ | 327 k – 375 k | 79Se₡ | |||||

| 1.53 M | 93Zr | |||||||

| 237Npƒ№ | 2.1 M – 6.5 M | 135Cs₡ | 107Pd | |||||

| 236U№ | 247Cmƒ | 15 M – 24 M | 129I₡ | |||||

| 244Pu№ | 80 M |

... nor beyond 15.7 M years[5] | ||||||

| 232Th№ | 238U№ | 235Uƒ№ | 0.7 G – 14.1 G | |||||

|

Legend for superscript symbols | ||||||||

Americium (Am) is an artificial element, and thus a standard atomic mass cannot be given. Like all artificial elements, it has no known stable isotopes. The first isotope to be synthesized was 241Am in 1944. The artificial element decays into alpha particles. Americium has an atomic number of 95 (the number of protons in the nucleus of the americium atom).

Nineteen radioisotopes of americium have been characterized, with the most stable being 243Am with a half-life of 7,370 years, and 241Am with a half-life of 432.2 years. All of the remaining radioactive isotopes have half-lives that are less than 51 hours, and the majority of these have half-lives that are less than 100 minutes. This element also has 8 meta states, with the most stable being 242mAm (t1/2 141 years). The isotopes of americium range in atomic weight from 231.046 u (231Am) to 249.078 u (249Am).

Some notable isotopes

Americium-241

Americium-241 is the most prevalent isotope of americium in nuclear waste.[6] It is the americium isotope used in an americium smoke detector based on an ionization chamber. It is a potential fuel for long-lifetime radioisotope thermoelectric generators.

| Parameter | Value |

|---|---|

| Atomic mass | 241.056829 u |

| Mass excess | 52930 keV |

| Beta decay energy | -767 keV |

| Spin | 5/2− |

| Half-life | 432.6 years |

| Spontaneous fissions | 1200 per kg s |

| Decay heat | 114 watts/kg |

Possible parent nuclides: beta from 241Pu, electron capture from 241Cm, alpha from 245Bk.

Americium-241 decays by alpha emission, with a by-product of gamma rays. Its presence in plutonium is determined by the original concentration of plutonium-241 and the sample age. Because of the low penetration of alpha radiation, Americium-241 only poses a health risk when ingested or inhaled. Older samples of plutonium containing plutonium-241 contain a buildup of 241Am. A chemical removal of americium from reworked plutonium (e.g. during reworking of plutonium pits) may be required.

Americium-242m

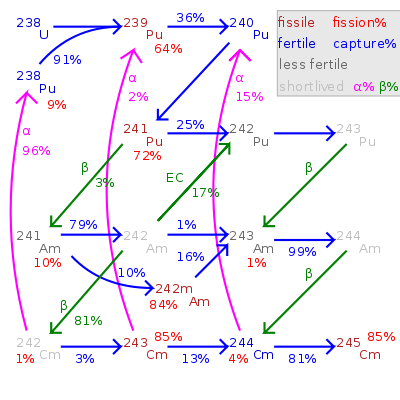

Fission percentage is 100 minus shown percentages.

Total rate of transmutation varies greatly by nuclide.

245Cm–248Cm are long-lived with negligible decay.

| Probability | Decay mode | Decay energy | Decay product |

|---|---|---|---|

| 99.54% | isomeric transition | 0.05 MeV | 242Am |

| 0.46% | alpha decay | 5.64 MeV | 238Np |

| (1.5±0.6) × 10−10 [8] | spontaneous fission | ~200 MeV | fission products |

Americium-242m has a mass of 242.0595492 g/mol. It is one of the rare cases, like 180mTa, where a higher-energy nuclear isomer is more stable than the lower-energy one, Americium-242.[9]

242mAm is fissile (because it has an odd number of neutrons) and has a low critical mass, comparable to that of 239Pu.[10] It has a very high cross section for fission, and if in a nuclear reactor is destroyed relatively quickly. Another report claims that 242mAm has a much lower critical mass, can sustain a chain reaction even as a thin film, and could be used for a novel type of nuclear rocket.[11][12]

| Probability | Decay mode | Decay energy | Decay product |

|---|---|---|---|

| 82.70% | beta decay | 0.665 MeV | 242Cm |

| 17.30% | electron capture | 0.751 MeV | 242Pu |

Americium-243

Americium-243 has a mass of 243.06138 g/mol and a half-life of 7,370 years, the longest lasting of all americium isotopes. It is formed in the nuclear fuel cycle by neutron capture on plutonium-242 followed by beta decay.[13] Production increases exponentially with increasing burnup as a total of 5 neutron captures on 238U are required.

It decays by either emitting an alpha particle (with a decay energy of 5.27 MeV)[13] to become 239Np, which then quickly decays to 239Pu, or infrequently, by spontaneous fission.[14]

243Am is a hazardous substance, because it can cause cancer. 239Np, which is formed from 243Am, emits dangerous gamma rays, making 243Am the most dangerous isotope of Americium.[6]

Table

| nuclide symbol |

Z(p) | N(n) | isotopic mass (u) |

half-life | decay mode(s)[15][n 1] |

daughter isotope(s) |

nuclear spin |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| excitation energy | |||||||

| 229Am[16] | 95 | 134 | 3.7 s | α | 225Np | ||

| 231Am | 95 | 136 | 231.04556(32)# | 30# s | β+ | 231Pu | |

| α (rare) | 227Np | ||||||

| 232Am | 95 | 137 | 232.04659(32)# | 79(2) s | β+ (98%) | 232Pu | |

| α (2%) | 228Np | ||||||

| β+, SF (.069%) | (various) | ||||||

| 233Am | 95 | 138 | 233.04635(11)# | 3.2(8) min | β+ | 233Pu | |

| α | 229Np | ||||||

| 234Am | 95 | 139 | 234.04781(22)# | 2.32(8) min | β+ (99.95%) | 234Pu | |

| α (.04%) | 230Np | ||||||

| β+, SF (.0066%) | (various) | ||||||

| 235Am | 95 | 140 | 235.04795(13)# | 9.9(5) min | β+ | 235Pu | 5/2−# |

| α (rare) | 231Np | ||||||

| 236Am | 95 | 141 | 236.04958(11)# | 3.6(1) min | β+ | 236Pu | |

| α | 232Np | ||||||

| 237Am | 95 | 142 | 237.05000(6)# | 73.0(10) min | β+ (99.97%) | 237Pu | 5/2(−) |

| α (.025%) | 233Np | ||||||

| 238Am | 95 | 143 | 238.05198(5) | 98(2) min | β+ | 238Pu | 1+ |

| α (10−4%) | 234Np | ||||||

| 238mAm | 2500(200)# keV | 35(10) µs | |||||

| 239Am | 95 | 144 | 239.0530245(26) | 11.9(1) h | EC (99.99%) | 239Pu | (5/2)− |

| α (.01%) | 235Np | ||||||

| 239mAm | 2500(200) keV | 163(12) ns | (7/2+) | ||||

| 240Am | 95 | 145 | 240.055300(15) | 50.8(3) h | β+ | 240Pu | (3−) |

| α (1.9×10−4%) | 236Np | ||||||

| 241Am[n 2] | 95 | 146 | 241.0568291(20) | 432.2(7) y | α | 237Np | 5/2− |

| CD (7.4×10−10%) | 207Tl, 34Si | ||||||

| SF (4.3×10−10%) | (various) | ||||||

| 241mAm | 2200(100) keV | 1.2(3) µs | |||||

| 242Am | 95 | 147 | 242.0595492(20) | 16.02(2) h | β− (82.7%) | 242Cm | 1− |

| EC (17.3%) | 242Pu | ||||||

| 242m1Am | 48.60(5) keV | 141(2) y | IT (99.54%) | 242Am | 5− | ||

| α (.46%) | 238Np | ||||||

| SF (1.5×10−8%) | (various) | ||||||

| 242m2Am | 2200(80) keV | 14.0(10) ms | (2+,3−) | ||||

| 243Am[n 2] | 95 | 148 | 243.0613811(25) | 7,370(40) y | α | 239Np | 5/2− |

| SF (3.7×10−9%) | (various) | ||||||

| 244Am | 95 | 149 | 244.0642848(22) | 10.1(1) h | β− | 244Cm | (6−)# |

| 244mAm | 86.1(10) keV | 26(1) min | β− (99.96%) | 244Cm | 1+ | ||

| EC (.0361%) | 244Pu | ||||||

| 245Am | 95 | 150 | 245.066452(4) | 2.05(1) h | β− | 245Cm | (5/2)+ |

| 246Am | 95 | 151 | 246.069775(20) | 39(3) min | β− | 246Cm | (7−) |

| 246m1Am | 30(10) keV | 25.0(2) min | β− (99.99%) | 246Cm | 2(−) | ||

| IT (.01%) | 246Am | ||||||

| 246m2Am | ~2000 keV | 73(10) µs | |||||

| 247Am | 95 | 152 | 247.07209(11)# | 23.0(13) min | β− | 247Cm | (5/2)# |

| 248Am | 95 | 153 | 248.07575(22)# | 3# min | β− | 248Cm | |

| 249Am | 95 | 154 | 249.07848(32)# | 1# min | β− | 249Cm | |

- ↑ Abbreviations:

CD: Cluster decay

EC: Electron capture

IT: Isomeric transition

SF: Spontaneous fission - 1 2 Most common isotopes

Notes

- Values marked # are not purely derived from experimental data, but at least partly from systematic trends. Spins with weak assignment arguments are enclosed in parentheses – ( ).

- Uncertainties are given in concise form in parentheses after the corresponding last digits. Uncertainty values denote one standard deviation, except isotopic composition and standard atomic mass from IUPAC, which use expanded uncertainties.

See also

References

- ↑ Plus radium (element 88). While actually a sub-actinide, it immediately precedes actinium (89) and follows a three-element gap of instability after polonium (84) where no isotopes have half-lives of at least four years (the longest-lived isotope in the gap is radon-222 with a half life of less than four days). Radium's longest lived isotope, at 1,600 years, thus merits the element's inclusion here.

- ↑ Specifically from thermal neutron fission of U-235, e.g. in a typical nuclear reactor.

- ↑ Milsted, J.; Friedman, A. M.; Stevens, C. M. (1965). "The alpha half-life of berkelium-247; a new long-lived isomer of berkelium-248". Nuclear Physics. 71 (2): 299. doi:10.1016/0029-5582(65)90719-4.

"The isotopic analyses disclosed a species of mass 248 in constant abundance in three samples analysed over a period of about 10 months. This was ascribed to an isomer of Bk248 with a half-life greater than 9 y. No growth of Cf248 was detected, and a lower limit for the β− half-life can be set at about 104 y. No alpha activity attributable to the new isomer has been detected; the alpha half-life is probably greater than 300 y." - ↑ This is the heaviest isotope with a half-life of at least four years before the "Sea of Instability".

- ↑ Excluding those "classically stable" isotopes with half-lives significantly in excess of 232Th; e.g., while 113mCd has a half-life of only fourteen years, that of 113Cd is nearly eight quadrillion years.

- 1 2 "Americium". Argonne National Laboratory, EVS. Retrieved 25 December 2009.

- ↑ Sasahara, Akihiro; Matsumura, Tetsuo; Nicolaou, Giorgos; Papaioannou, Dimitri (April 2004). "Neutron and Gamma Ray Source Evaluation of LWR High Burn-up UO2 and MOX Spent Fuels". Journal of Nuclear Science and Technology. 41 (4): 448–456. doi:10.3327/jnst.41.448.

- ↑ J. T. Caldwell; S. C. Fultz; C. D. Bowman; R. W. Hoff (March 1967). "Spontaneous Fission Half-Life of Am242m242m". Physical Review. 155: 1309–1313. doi:10.1103/PhysRev.155.1309. (halflife (9.5±3.5)×1011

- ↑ 95-Am-242

- ↑ (PDF) http://typhoon.jaea.go.jp/icnc2003/Proceeding/paper/6.5_022.pdf. Retrieved February 3, 2011. Missing or empty

|title=(help) - ↑ "Extremely Efficient Nuclear Fuel Could Take Man To Mars In Just Two Weeks" (Press release). Ben-Gurion University Of The Negev. December 28, 2000.

- ↑ Ronen, Yigal; Shwageraus, E. (2000). "Ultra-thin 241mAm fuel elements in nuclear reactors". Nuclear Instruments and Methods in Physics Research A. 455: 442–451. doi:10.1016/s0168-9002(00)00506-4.

- 1 2 "Americium-243". Oak Ridge National Laboratory. Retrieved 25 December 2009.

- ↑ "Isotopes of the Element Americium". Jefferson Lab Science Education. Retrieved 25 December 2009.

- ↑ "Universal Nuclide Chart". nucleonica. (registration required (help)).

- ↑ "Observation of new neutron-deficient isotopes with Z ≥ 92 in multinucleon transfer reactions" http://inspirehep.net/record/1383747/files/scoap3-fulltext.pdf

Sources

- Isotope masses from:

- Audi, G.; Wapstra, A. H.; Thibault, C.; Blachot, J.; Bersillon, O. (2003). "The NUBASE evaluation of nuclear and decay properties" (PDF). Nuclear Physics A. 729: 3–128. Bibcode:2003NuPhA.729....3A. doi:10.1016/j.nuclphysa.2003.11.001.

- Isotopic compositions and standard atomic masses from:

- de Laeter, J. R.; Böhlke, J. K.; De Bièvre, P.; Hidaka, H.; Peiser, H. S.; Rosman, K. J. R.; Taylor, P. D. P. (2003). "Atomic weights of the elements. Review 2000 (IUPAC Technical Report)". Pure and Applied Chemistry. 75 (6): 683–800. doi:10.1351/pac200375060683.

- Wieser, M. E. (2006). "Atomic weights of the elements 2005 (IUPAC Technical Report)". Pure and Applied Chemistry. 78 (11): 2051–2066. doi:10.1351/pac200678112051. Lay summary.

- Half-life, spin, and isomer data selected from the following sources.

- Audi, G.; Wapstra, A. H.; Thibault, C.; Blachot, J.; Bersillon, O. (2003). "The NUBASE evaluation of nuclear and decay properties" (PDF). Nuclear Physics A. 729: 3–128. Bibcode:2003NuPhA.729....3A. doi:10.1016/j.nuclphysa.2003.11.001.

- "NuDat 2.1 database". NNDC.BNL.gov. Brookhaven National Laboratory. Retrieved September 2005. Check date values in:

|access-date=(help) - Holden, N. E. (2004). "Table of the Isotopes". In D. R. Lide. CRC Handbook of Chemistry and Physics (85th ed.). CRC Press. Section 11. ISBN 978-0-8493-0485-9.

| Isotopes of plutonium | Isotopes of americium | Isotopes of curium |

| Table of nuclides | ||

| Isotopes of the chemical elements | |||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 H |

2 He | ||||||||||||||||

| 3 Li |

4 Be |

5 B |

6 C |

7 N |

8 O |

9 F |

10 Ne | ||||||||||

| 11 Na |

12 Mg |

13 Al |

14 Si |

15 P |

16 S |

17 Cl |

18 Ar | ||||||||||

| 19 K |

20 Ca |

21 Sc |

22 Ti |

23 V |

24 Cr |

25 Mn |

26 Fe |

27 Co |

28 Ni |

29 Cu |

30 Zn |

31 Ga |

32 Ge |

33 As |

34 Se |

35 Br |

36 Kr |

| 37 Rb |

38 Sr |

39 Y |

40 Zr |

41 Nb |

42 Mo |

43 Tc |

44 Ru |

45 Rh |

46 Pd |

47 Ag |

48 Cd |

49 In |

50 Sn |

51 Sb |

52 Te |

53 I |

54 Xe |

| 55 Cs |

56 Ba |

|

72 Hf |

73 Ta |

74 W |

75 Re |

76 Os |

77 Ir |

78 Pt |

79 Au |

80 Hg |

81 Tl |

82 Pb |

83 Bi |

84 Po |

85 At |

86 Rn |

| 87 Fr |

88 Ra |

|

104 Rf |

105 Db |

106 Sg |

107 Bh |

108 Hs |

109 Mt |

110 Ds |

111 Rg |

112 Cn |

113 Nh |

114 Fl |

115 Mc |

116 Lv |

117 Ts |

118 Og |

| |

57 La |

58 Ce |

59 Pr |

60 Nd |

61 Pm |

62 Sm |

63 Eu |

64 Gd |

65 Tb |

66 Dy |

67 Ho |

68 Er |

69 Tm |

70 Yb |

71 Lu | ||

| |

89 Ac |

90 Th |

91 Pa |

92 U |

93 Np |

94 Pu |

95 Am |

96 Cm |

97 Bk |

98 Cf |

99 Es |

100 Fm |

101 Md |

102 No |

103 Lr | ||

| |||||||||||||||||