Klang (city)

| Bandaraya Klang | ||

|---|---|---|

| Charter City | ||

|

The palace of the Sultan of Selangor in Klang | ||

| ||

| Nickname(s): Klang | ||

|

Motto: Perpaduan Sendi Kekuatan (Malay) "Strength Through Unity" | ||

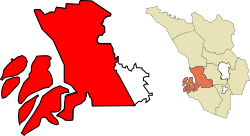

Location of area under MP Klang (red) within the Klang District (orange), and the state of Selangor (yellow). | ||

Bandaraya Klang Location of area under MP Klang (red) within the Klang District (orange), and the state of Selangor (yellow). | ||

| Coordinates: 3°02′N 101°27′E / 3.033°N 101.450°E | ||

| Country | Malaysia | |

| State | Selangor | |

| Granted Municipal Status | 1 January 1977 | |

| Government | ||

| • Administered by | Klang Municipal Council | |

| • Yang diPertua (President) | Datuk Mohd Yazid Bidin[1] | |

| Area | ||

| • Total | 573 km2 (202 sq mi) | |

| Population (2010) | ||

| • Total | 744,062 | |

| • Density | 1,298/km2 (3,360/sq mi) | |

| Time zone | MST (UTC+8) | |

| • Summer (DST) | Not observed (UTC) | |

| Website |

mpklang | |

Klang or Kelang, officially Klang City (Malay: Bandaraya Klang), is a royal town and former capital of the state of Selangor, Malaysia. It is located within the Klang District. It was the civil capital of Selangor in an earlier era prior to the emergence of Kuala Lumpur and the current capital, Shah Alam. Port Klang, which is located in the Klang District, is the 13th busiest transshipment port[2] and the 16th busiest container port in the world.

The Klang Municipal Council or MP Klang exercises jurisdiction for a majority of the Klang District while the Shah Alam City Council exercises some jurisdiction over the east of Klang District, north of Petaling District and the other parts of Selangor State including Shah Alam itself.

As of 2010, the Klang City has a total population of 240,016 (10,445 in the city centre), while the population of Klang District is 842,146, and the population of all towns managed by Klang Municipal Council is 744,062.[3]

History

[5][6] Iron age tools called "tulang mawas" ("ape bones") have also been found in Klang.[7] Commanding the approaches to the tin rich Klang Valley, Klang has always been of key strategic importance. It was mentioned as a dependency of other states as early as the 11th century.[8] Klang was also mentioned in the 14th century literary work Nagarakretagama dated to the Majapahit Empire, and the Klang River was already marked and named on the earliest maritime charts of Chinese Admiral Cheng Ho on his visits to Malacca from 1409 to 1433.[9]

The celebrated Tun Perak, the Malacca Sultanate's greatest Bendahara, came from Klang and became its territorial chief. After the fall of Melaka to the Portuguese in 1511, Klang remained in Malay hands, controlled by the Sultan Johor-Riau until the creation of Selangor sultanate in the 18th century. Klang was also once known as Pengkalan Batu meaning "stone jetty".[10]

In the 19th century the importance of Klang greatly increased by the rapid expansion of tin mining as a result of the increased demand for tin from the West. The desire to control the Klang Valley led directly to the Selangor Civil War (also called the Klang War) of 1867–1874 when Raja Mahdi fought to regain what he considered his birthright as territorial chief against Raja Abdullah.[11] During the Klang War, in 1868, the seat of power was moved to Bandar Temasya, Kuala Langat,[9] and then to Jugra which became the royal capital of Selangor.[12] Klang however did not lose its importance. Until the construction of Port Swettenham (now known as Port Klang) in 1901, Klang remained the chief outlet for Selangor's tin, and its position was enhanced by the completion of the Klang Valley railway (to Bukit Kuda) in 1886. In the 1890s its growth was further stimulated by the development of the district into the State' leading producer of coffee, and later rubber. In 1903, the royal seat was moved back to Klang when it became the official seat of Sultan Sulaiman (Sultan Alauddin Sulaiman Shah).

In 1874, Selangor accepted a British Resident who would "advise" the Sultan, and Klang became the capital of British colonial administration for Selangor from 1875 until 1880 when the capital city was moved to Kuala Lumpur.[13][14] Today Klang is no longer State capital or the main seat of the ruler, but it remains the headquarters of the District to which it gives it name.

In May 1890, a local authority, known as Klang Health Board, was established to administer Klang town. The official boundary of Klang was first defined in 1895. In 1926 the health boards of Klang and Port Swettenham were merged, and in 1945 the local authority was renamed Klang Town Board.[15] In 1954, the Town Board became the Klang Town Council after a local election was set up to select its members in accordance with the Local Government Election Ordinance of 1950. In 1963, the Port Klang Authority was created and it now administers three Port Klang areas: Northport, Southpoint, and West Port.[16]

In 1971, the Klang District Council, which incorporated the nearby townships of Kapar and Meru as well as Port Klang, was formed. After undergoing a further reorganisation according to the Local Government Act of 1976 (Act 171), Klang District Council was upgraded to Klang Municipal Council (KMC) on 1 January 1977.[15] From 1974 to 1977, Klang was the state capital of Selangor before the seat of government shifted to Shah Alam in 1977.[9]

Etymology

Klang may have taken its name from the Klang River which runs through the town. The entire geographical area in the immediate vicinity of the river, which begins at Kuala Lumpur and runs west all the way to Port Klang, is known as the Klang Valley.

One popular theory on the origin of the name is that it is derived from the Mon–Khmer word Klong.[17] The word may mean a canal or waterway,[17] alternatively it has also been argued that it means "warehouses", from the Malay word Kilang – in the old days, it was full of warehouses (kilang currently means "factory").[18]

Districts

.jpg)

Klang is divided into North Klang and South Klang, which are separated by the Klang River. North Klang is divided into three sub-districts which are Kapar (Located at the north of North Klang), Rantau Panjang (situated at the west of North Klang) and Meru (at the east of North Klang).

Klang North used to be the main commercial centre of Klang, but since 2008, more residential and commercial areas as well as government offices are being developed in Klang South. Most major government and private health care facilities are also located at Klang South. Hence, this area tends to be busier and becomes the centre of social and recreational activities after office hours and during the weekends. This is triggered by the rapid growth of new and modern townships such as Bandar Botanic, Bandar Bukit Tinggi, Taman Bayu Perdana, Glenmarie Cove, Kota Bayuemas etc. all located within Klang South.

At the Klang North side, some of the older and established residential areas include Berkeley Garden, Taman Eng Ann, Taman Klang Utama, Bandar Baru Klang and so forth. Newer townships include Bandar Bukit Raja, Aman Perdana and Klang Sentral.

Malaysia's busiest port, Port Klang is located at Klang South.

Economy

The economy of Klang is closely linked with that the greater Klang Valley conurbation which is the most densely populated, urbanised and industrialised region of Malaysia.[19] There is a wide range of industries within the Klang municipality, major industrial areas may be found in Bukit Raja, Kapar, Meru, Taman Klang Utama and Sungai Buloh, Pulau Indah, Teluk Gong and others.[20] Rubber used to be an important part of the economy of the region, but from the 1970s onwards, many rubber plantations have switched to palm oil, and were then converted again for urban development and infrastructure use.[21][22]

Port Klang forms an important part of the economy of Klang. It is home to about 95 shipping companies and agents, 300 custom brokers, 25 container storage centres, as well as more than 70 freight and transport companies.[23] It handled almost 50% of Malaysia's sea-borne container trade in 2013.[24] The Port Klang Free Zone was established in 2004 to transform Port Klang into a regional distribution hub as well as a trade and logistics centre.[25]

Politics

Klang encompasses three parliamentary seats: Kapar (Mr. Manikavasagam a/l Sundaram of PKR), Kota Raja (Mdm. Siti Mariah Mahmud of Amanah), and Klang (Mr. Charles Anthony Santiago of DAP). All three are held by the Pakatan Harapan coalition. These constituencies are subdivided into state seats.

Demographics

The following are the census figures for the population of Klang. The 1957 and 1970 figures are for the Klang district and were collected before Klang reorganisation and Bumiputra status being used as a category. The 2010 figures are for MP Klang. The figure for Klang city is not given as what constitutes Bandar Klang appears to be inconsistent with considerable fluctuation in numbers over the years.

| Ethnic Group | Population | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1957[26] | 1970[26] | 2010[27] | ||||

| Malay | 37,003 | 24.68% | 72,734 | 31.13% | 335,739 | 45.12% |

| Other Bumiputras | 9,107 | 1.22% | ||||

| Bumiputra total | 344,846 | 46.34% | ||||

| Chinese | 65,454 | 43.65% | 100,524 | 43.02% | 190,854 | 25.65% |

| Indian | 44,393 | 29.60% | 59,333 | 25.39% | 140,519 | 18.89% |

| Others | 3,105 | 2.07% | 1,079 | 0.46% | 3,573 | 0.48% |

| Malaysian total | 679,792 | 91.36% | ||||

| Non-Malaysian | 64,270 | 8.64% | ||||

| Total | 149,955 | 100.00% | 233,670 | 100.00% | 744,062 | 100.00% |

Crime

There are a number of criminal gangs operating in Klang, and gang violence is not uncommon.[28][29] Among the Chinese community, there are the Ang Bin Hoey triad gangs such as Gang 21 which operates in Kuala Lumpur and the Klang Valley.[30] There are also Gang 24,[31] Gang 36 and others,[32] and their members are often Indians.[33] Due to economic development and changes in the industry, many rubber estates where Indian plantation workers used to live and work were closed, and this is thought to have contributed to a rise of gangsterism amongst the displaced and economically-deprived Indians.[34][35] It is thought that the Indians originally worked for Chinese gang leaders but they now dominate many of these criminal organisations.[33]

Transportation

Klang is served by five commuter stations that constitute the Batu Caves-Port Klang Route of the KTM Komuter system, namely the Bukit Badak Komuter station, the Kampung Raja Uda Komuter station, the Klang Komuter station, the Teluk Pulai Komuter station and the Teluk Gadong Komuter station.

Klang is well connected to the rest of the Klang Valley via the Federal Highway, the New Klang Valley Expressway, South Klang Valley Expressway, the North Klang Straits Bypass (New North Klang Straits Bypass) as well as the KESAS Highway.

Klang is also served by the RapidKL bus route. Klang Sentral acts as a terminal for buses and taxis in northern Klang.

Infrastructure and developments

Shopping complexes

There are several shopping complexes and hypermarkets in Klang, primarily in Klang South, namely:

- ÆON Bukit Tinggi Shopping Centre (Bandar Bukit Tinggi)

- ÆON Bukit Raja Shopping Centre (Bandar Baru Klang)

- ÆON Big Hypermarket (Kapar Road)

- Big(TUNE) Mall (formerly known as Harbour Place Shopping Mall) (Persiaran Raja Muda Musa)

- Centro Mall

- Giant Hypermarket (Bandar Bukit Tinggi, Klang Sentral)

- GM Klang Wholesale City (Bandar Botanic) – Major in Wholesale Business

- Klang Parade (Meru Road)

- KSL City Mall @ Klang (Bandar Bestari) – planned, and set to be the largest shopping mall in Klang.[36]

- Shaw Centrepoint (Klang Town)

- Tesco Extra (Bandar Bukit Tinggi)

Hospitals and medical centres

- Hospital Tengku Ampuan Rahimah (Klang General Hospital), Jalan Langat

- Manipal Hospitals Klang, Bandar Bukit Tinggi

- Pantai Hospital Klang, Persiaran Raja Muda Musa, Port Klang

- Sri Kota Medical Centre, Jalan Mohet

- KO Specialist Center Klang, Jalan Goh Hock Huat

- KPJ Klang Specialist Hospital, Bandar Baru Klang

- Metro Maternity Hospital, Jalan Pasar

- Sentosa Specialist Hospital

- Hospital Bersalin Razif, Taman Sri Andalas

- Columbia Asia Hospital Klang, Bandar Bukit Raja (under construction)

- Klinik Kesihatan Bandar Botanic (Government health clinic)

Local landmarks and attractions

- Istana Alam Shah – The royal residence of the Sultan of Selangor was built in 1950 in south Klang to replace the old Mahkota Puri Palace. Parts of the Palace are accessible to the public but only on a few days of the week.[37] Near the Palace is the Klang Royal City Park (Taman Bandar Diraja Klang), and located in front of the Palace is a sports stadium (Stadium Padang Sultan Sulaiman) and the Royal Klang Club.

- Sultan Sulaiman Royal Mosque – The royal Mosque was built in 1932.

- Church of Our Lady of Lourdes – Built in 1928, the church celebrated its Golden Jubilee in 2008 after the church building had undergone restoration. Father Souhait played a large part in the design of the church building, modelling it on the pilgrimage church in Lourdes, France. The design of the church follows the style of a Gothic architecture.

- Kota Raja Mahadi – This historic fort was actually an arch of the fort. In the old days, there was a struggle between Raja Mahadi and Raja Abdullah for the control of the Klang district.

- Tugu Keris (Keris Monument) – A memorial erected to commemorate the Silver Jubilee of the Sultan of Selangor's installation in 1985. The monument is specially designed to depict the Keris Semenanjung that symbolises power, strength and unity.

- Kai Hong Hoo (开封府) – The only temple in Malaysia dedicated to the worship of Justice Bao (包公), who was a government officer in ancient China's Song Dynasty. Justice Bao consistently demonstrated extreme honesty and uprightness and is today respected as the cultural symbol of justice in the Chinese community worldwide.

- Tanjung Harapan (The Esplanade) – Fronting the Straits of Malacca, the Esplanade is a sea-side family recreation spot near to Northport that houses several seafood restaurants. Nice setup for sunset-gazing and also for anglers to fish.

- Little India (Klang) – Colourful street from the striking saris hanging from shops to the snacks and sweetmeats on sale from shops and roadside stalls. During Deepavali, the Indian festival of lights, the street is astoundingly transformed into a colourful spectacle of lights and booming sound of music.

- Sri Sundararaja Perumal Temple – Built in 1896, it is one of the oldest and the largest of the Vaishnavite temples in Malaysia. The temple is often referred to as the "Thirupathi of South East Asia" after its famous namesake in India.

- Sri Subramania Swamy Temple,Klang – A Hindu temple devoted to the worship of Lord Murugan in Teluk Pulai,Klang that was established on 14 February 1914. It holds a unique distinction among the Hindu temples in Klang as it was founded and managed by the Ceylonese/Sri Lankan community who lived around the vicinity of the temple. Prayer rituals are done like those in Sri Lanka and certain festivals specific to the Ceylonese/Jaffnese community are celebrated here. The arasamaram or sacred fig tree which is in the temple was there since 1914 and is possibly one of the oldest living tree in Klang.

- Kuan Im Teng Klang (巴生观音亭)(Goddess of Mercy Temple) – Kuan Im Teng (as pronounced in the Hokkien dialect) is over 100 years old. This Goddess of Mercy Temple is located at the Jalan Barat Daya, near Simpang Lima. Bustling with devotees during the first day and the fifteenth day of lunar calendar. It is one of the oldest temple in Malaya since colonial period, It was established during 1892. The temple is also involved in charity work, contributing to several health and educational organisations. On the eve of Chinese New Year, the temple is opened all night and the street is often packed with devotees queuing shoulder to shoulder to enter the temple hall to offer their incense to the Kwan Yin in hope for an auspicious start to the New Year.

- Connaught Bridge is one of the oldest bridge in Malaysia's Klang Valley region. It was built in 1948 by the British. The bridge is located in Jalan Dato' Mohd Sidin (Federal route ) near Connaught Bridge Power Station in Klang Selangor. At one time, Connaught bridge can only be crossed one vehicle at a time. No lorry could pass it because it was limited to car, van and small vehicle only. While on the bridge, you will heard the sound of wood 'cracking'! The wooden bridge closed in 1993–1994. In 1995 the wooden bridge was replaced by a concrete box girder bridge.

- Jambatan Kota is the first double-decked bridge in Malaysia and is located in Klang, Selangor. The bottom deck is a pedestrian walkway bridge while the top deck is a motorist bridge. The bridge was closed to car traffic in the '90s due to high demand that necessitated the construction of a new bridge. The new Jambatan Kota is located beside of the old bridge. The old bridge was constructed between 1957 and 1960, and was officially opened in 1961 by the late Sultan of Selangor, Almarhum Sultan Salahuddin Abdul Aziz Shah as part of the celebration of his coronation as the ninth Sultan of Selangor.

- Sultan Abdul Aziz Royal Gallery is the royal gallery located at Bangunan Sultan Suleiman, Klang. Various collections depicting the reign of Sultan Salahuddin Abdul Aziz Shah; from his early childhood through his appointment as the eighth Sultan Selangor in 1960 and as the eleventh Yang di-Pertuan Agong in 1999.

Cuisine

Malay food

The most significant food spot in Klang is at "Emporium Makan", this old spot situated in the heart the city, opposite of Pasar Jawa and next to Jambatan Kota. One of the popular stalls is "Lontong Klang". This is the first stall and visited by all races, Malay, Chinese and Indian, and still open until now. They sell the unforgettable dishes such as, lontong and nasi lemak sambal sotong.

Chinese food

Klang is well known for its Bak Kut Teh (Chinese: 肉骨茶, Pinyin: Ròu Gŭ Chá), a herbal soup that uses pork ribs and tenderloins. The dish is popularly thought to have originated in Klang.[38] Bak Kut Teh is popular in various locations including Taman Intan (previously called Taman Rashna), Teluk Pulai, Jalan Kereta Api and Pandamaran.

There are a number of foodcourts in Klang which served local cuisine. Located in Taman Eng Ann is a large foodcourt serving many daytime snacks ranging from the well-known Chee Cheong Fun, Yong Tau Foo, Popia (Chinese springrolls), the medicinal herb Lin Zhi Kang drink, to Rojak and Cendol. Other stalls found also serving Chee Cheong Fun in Klang are located around the Meru Berjaya area. The Yong Tau Foo, a Malaysian Hakka Chinese delicacy, is a popular meal for lunch and dinner as well.

Seafood

The coastal regions and islands near Port Klang are also well known for their seafood, such as Pulau Ketam, Bagan Hailam,[39] Teluk Gong,[40] Pandamaran and Tanjung Harapan.[41]

Education

Schools

- Klang High School

- SMJK Kwang Hua, Klang

- SRK Jalan Batu Tiga (1) & (2)

- Bukit Kuda Girls' School

- Anglo Chinese School, Klang

- La Salle School, Klang

- SMK Convent Klang

- Methodist Girls' School, Klang

- Sri Istana School

- Sri Lethia School

- Sri Acmar School

- SMK Tengku Ampuan Rahimah

- SMK Tengku Ampuan Jemaah

- SRK Simpang Lima (1) & (2)

- Kolej Islam Sultan Alam Shah

- SMK Kota Kemuning

- SMK Jalan Kebun

- SAMT Sultan Hisamuddin Kampung Jawa

- SMK Sungai Kapar Indah

- SMK Raja Mahadi

- SMK Tengku Idris Shah

- Regent International School

- SMK Meru

- SMK Sri Andalas

- SMK Batu Unjur

- SRK Batu Unjur

- SRK Bukit Tinggi

- SRK Jalan Kebun

- SK Sungai Binjai

- SRA Jalan kebun

- SJK(T) Simpang Lima

- SMK Pendamaran Jaya

- Smk Rantau Panjang,Klang

International relations

Sister cities

Klang currently has three sister cities:

|

References

- ↑ "Turning Klang into a clean town". The Star. Retrieved 24 November 2015.

- ↑ "PORT KLANG CELEBRATES OVER 100 YEARS OF BEING MALAYSIA'S PREMIER PORT". Port Klang Authority. Retrieved 15 May 2012.

- ↑ MPK, Klang. "TABURAN PENDUDUK DAN CIRI-CIRI ASAS DEMOGRAFI TAHUN 2010". MP Klang Site.

- ↑ British Museum Collection

- ↑ The Kettledrums of Southeast Asia: A Bronze Age World and Its Aftermath – August Johan Bernet Kempers – Google Books. Books.google.com.au. Retrieved 17 September 2013.

- ↑ W. Linehan (October 1951). "Traces of a Bronze Age Culture Associated With Iron Age Implements in the Regions of Klang and the Tembeling, Malaya". Journal of the Malayan Branch of the Royal Asiatic Society. Malaysian Branch of the Royal Asiatic Society. 24 (3 (156)): 1–59.

- ↑ R. O. Winstedt (October 1934). "A History of Selangor". Journal of the Malayan Branch of the Royal Asiatic Society. Malaysian Branch of the Royal Asiatic Society. 12 (3 (120)): 1–34.

- ↑ J.M. Gullick (1983). The Story of Kuala Lumpur, 1857–1939. Eastern Universities Press (M). p. 7. ISBN 978-9679080285.

- 1 2 3 "Background and History". Port Klang Integrated Coastal Management Project.

- ↑ JM Gullick (1955). "Kuala Lumpur 1880–1895" (PDF). Journal of the Malayan Branch of the Royal Asiatic Society. 24 (4): 10–11.

- ↑ A History of Malaysia – Barbara Watson Andaya, Leonard Y. Andaya – Google Books. Books.google.com.au. Retrieved 17 September 2013.

- ↑ Kon Yit Chin, Voon Fee Chen (2003). Landmarks of Selangor. Jugra Publications. p. 34.

- ↑ Prem Kumar Rajaram. Ruling the Margins: Colonial Power and Administrative Rule in the Past and Present. p. 35.

- ↑ Isabella Lucy Bird (1883). The Golden Chersonese and the Way Thither. pp. 271–272.

- 1 2 "Background". Klang Municipal Council.

- ↑ "Port Klang: Review and History". World Port Source.

- 1 2 "History". Klang Municipal Council.

- ↑ The town that tin built at the Wayback Machine (archived 31 October 2014)

- ↑ Ooi Keat Gin (2009). Historical Dictionary of Malaysia. Scarecrow Press. pp. 157–158. ISBN 978-0810859555.

- ↑ "Industrial Areas". Klang Municipal Council.

- ↑ Peter D. Tyson, ed. (2002). Global-Regional Linkages in the Earth System. Springer. p. 160.

- ↑ Garik Gutman et al. (2004). Land Change Science: Observing, Monitoring and Understanding Trajectories of Change on the Earth's Surface. Springer. p. 122. ISBN 978-9400743069.

- ↑ "Klang Introduction". Klang Chinese Chamber of Commerce and Industry.

- ↑ "Port Klang aims for 20 million TEUs". The Star. 2 July 2013.

- ↑ "Gateway" (PDF). Port Klang Authority. 2009.

- 1 2 Katiman Rostam. "Population Change of the Klang-Langat Extended Metropolitan Region, Maalaysia, 1957–2000" (PDF). Akademika. 79 (1): 1–18.

- ↑ "Table 13.1 : Total population by ethnic group, Local Authority area and state, Malaysia, 2010" (PDF). Department of Statistics, Malaysia. p. 181. Archived from the original (PDF) on 27 February 2012.

- ↑ "Brutal killings a sign of all-out gang war". The Malay Mail. 16 February 2015.

- ↑ G. Prakash (3 April 2015). "Chopped up teen linked to Klang gang war, cops say". The Malay Mail.

- ↑ Gregory F Treverton, Carl Matthies, Karla J Cunningham, Jeremiah Gouka, Greg Ridgeway (2009). Film Piracy, Organized Crime, and Terrorism. RAND Corporation. p. 68. ISBN 978-0833045652.

- ↑ Gregory F Treverton; Carl Matthies; Karla J Cunningham; Jeremiah Gouka; Greg Ridgeway (2009). Film Piracy, Organized Crime, and Terrorism. RAND Corporation. ISBN 978-0833045652.

- ↑ "'Tis the season for extortion". The Malaysian Insider. 18 February 2015.

- 1 2 "The 'Taikos' Behind Indian Gangs". Sin Chew Daily. 28 August 2013.

- ↑ C. E. R. Abraham (2006). Speaking Out: Insights Into Contemporary Malaysian Issues. Utusan Publications. p. 107. ISBN 9676117935.

- ↑ "Malaysia's gang menace". Al Jazeera. 11 July 2014.

- ↑ "Mega-mall coming up in Klang". The Star (Malaysia). 8 April 2015.

- ↑ "Istana Alam Shah".

- ↑ Su-Lyn Tan; Mark Tay (2003). Malaysia & Singapore. Lonely Planet. p. 140.

- ↑ Simon Richmond, Damian Harper. Malaysia, Singapore & Brunei. Lonely Planet. pp. 130–131. ISBN 978-1740593571.

- ↑ Charles de Ledesma, Mark Lewis, Pauline Savage (2003). The Rough Guide to Malaysia, Singapore and Brunei. Rough Guides. ISBN 978-1843530947.

- ↑ "Medan Muara Ikan Bakar @ Tanjung Harapan, Port Klang". Foodstreet.

- ↑ Yi Yanjun (2 September 2014). "Twin Towns and Sister Cities (Abroad)". Hong Shan. Archived from the original on 21 December 2015. Retrieved 21 December 2015.

- ↑ "List of Sister cities of Hunan". Hunan Government. Archived from the original on 21 December 2015. Retrieved 21 December 2015.

External links

-

Klang travel guide from Wikivoyage

Klang travel guide from Wikivoyage - Klang Online Magazine,Guide & Map

- Official portal of Klang Municipal Council (MPK)

| Preceded by first |

Capital of Selangor (1875–1880) |

Succeeded by Kuala Lumpur |

| Preceded by Kuala Lumpur |

Capital of Selangor (1974–1977) |

Succeeded by Shah Alam |

Coordinates: 3°02′N 101°27′E / 3.033°N 101.450°E