Kowloon–Canton Railway Corporation

|

The way ahead | |

| Statutory body | |

| Industry | Public transportation |

| Founded | Hong Kong, December 1982 |

| Headquarters | Fo Tan, Hong Kong |

Number of locations | Hong Kong |

Area served | Hong Kong |

| Website |

www |

The Kowloon–Canton Railway Corporation (KCRC; Chinese: 九廣鐵路公司) was established in 1982 under the Kowloon–Canton Railway Corporation Ordinance for the purposes of operating the Kowloon–Canton Railway (KCR), and to construct and operate other new railways. On 2 December 2007, the MTR Corporation Limited, another railway operator in Hong Kong, took over the operation of the KCR network under a 50-year service concession agreement, which can be extended. Under the service concession, KCRC retains ownership of the KCR network with the MTR Corporation Limited making annual payments to KCRC for the right to operate the network. The KCRC is wholly owned by the Hong Kong Government and its activities are governed by the KCRC Ordinance as amended in 2007 by the Rail Merger Ordinance to enable the service concession agreement to be entered into with the MTR Corporation Limited.[1]

History

Summary

From 1910 to 1982, the KCR network was operated as a department of the Hong Kong Government. The Kowloon–Canton Railway Corporation was created in December 1982 after the government decided to corporatise its railway department. Until 2007, the KCR owned and operated a network of heavy rail, light rail and feeder bus routes within Kowloon and the New Territories. It was also a land developer by utilising its property development rights atop and around railway stations and depots. In December 2007, it ceased railway operations, with its business becoming primarily that of earning revenue from being the holder of railway assets. While it continues to own the rail network, the network is operated by the MTR Corporation under a 50-year service concession, for which the MTR Corporation Limited makes annual payments to KCR.

Origins of the corporation

The events leading to the present day KCR go back over one hundred years. During the 19th century, the western colonial powers competed with each other to establish and maintain commercial and political spheres of influence in China. Hong Kong held a vital position in protecting British trading interests in South China.

The idea of connecting Hong Kong and China with a railway was first proposed to prominent Hong Kong businessmen in March 1864 by a British railway engineer, Sir Rowland MacDonald Stephenson, who had considerable experience of developing railways in India. The minutes of the committee of the Chamber of Commerce meeting in Hong Kong, where a letter setting out his ideas was considered on 7 March 1864, state that "the opinions of the Chamber in respect to his suggestions should be recorded in the form of a letter, to the effect that the Committee deem it essential for the advancement of the project that short lines of railway should at first only be tried, and that it is not advisable at present to interfere with any water communications which are already established and can generally be worked more cheaply than railway traffic."[2]

The main reason for this decision, which effectively killed MacDonald Stephenson's idea, was that many of the businessmen concerned had a personal interest in protecting their investments in the established shipping companies that enjoyed a monopoly on carriage of passengers and goods into and out of China.

It took a further 30 years before the idea of building a railway from Hong Kong to China was again given serious consideration. In the last decade of the 19th century increasing diplomatic and trade activity by France in Guangdong Province and the granting of a concession to Belgian interests to construct a railway from Peking (now Beijing) to Hankow (later extended to Canton (now Guangzhou)), led to British diplomatic and commercial concerns about protecting Hong Kong as the major trading port for South China.

The British Government extracted a number of railway concessions from the Chinese Government for the British & Chinese Corporation, a joint venture formed in 1898 between the trading company of Jardine Matheson & Co. and the Hong Kong and Shanghai Bank. These concessions included the right to construct and operate a railway from Kowloon to Canton that would link to the Peking-Hankow-Canton line.

While the British & Chinese Corporation undertook a preliminary survey of the proposed route of the line in 1899, the financial uncertainties created by the Boxer Rebellion in China (1899–1901) and the Boer War (1899–1902) in South Africa made it difficult for the Corporation to raise funds for the project. However, by the beginning of the 20th century, the Hong Kong Government under the leadership of the colony's governor, Sir Henry Blake, decided that urgent action was required.

Discussions between the Colonial Office in London, the Hong Kong Government and the British & Chinese Corporation, led to an agreement in late 1904 that the Hong Kong Government would undertake the financing, construction and operation of the section of the line within Hong Kong. The remaining section to Guangzhou would be financed through a loan raised by the British & Chinese Corporation on behalf of the Chinese Government, which would operate the section after its construction by the corporation.

Settling the detailed financing arrangements for the British and Chinese sections proved to be complicated, because the funding of the British Section (as it became known) depended on the raising of the loan for the Chinese Section. The arrangements were finally ratified by the Hong Kong Government's passage of the Railway Loans Ordinance in 1905, clearing the way for construction of the British Section. It took until 1907, however, for the loan agreement for the Chinese Section to be concluded, with the financing being provided by way of a bond issue floated in London in April of the same year.

The importance attached to the project was reflected in a speech made to the Hong Kong Legislative Council by the colonial governor, Sir Frederick Lugard, in 1908:

"You will recall that in 1905 it was decided to build the railway by means of a loan. It was not a question of whether the undertaking would be an immediately remunerative concern; it was not a question of whether the railway should pay interest and sinking fund on the capital expended, or even if it would at once pay working expenses. It was a question of preserving the predominance of Hong Kong. It was a question of seeing that the final outlet of the main trunk railway should be at Kowloon, and at no other place."

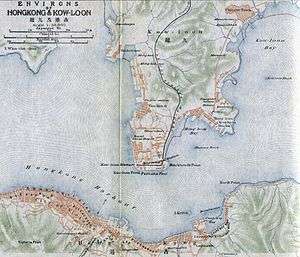

Two routes were suggested for the British Section, a western route of about 34 miles (55 km) from the tip of Kowloon peninsula via Tsuen Wan to Castle Peak Bay and thence to Yuen Long and the border with China, and a more direct eastern route of about 21 miles (34 km) requiring tunnelling through the Kowloon hills and thence to the border via Tide Cove (Sha Tin), Tai Po, Fanling and Sheung Shui. Following a detailed survey in 1905, the eastern route was proposed. Although the formal approval of the Colonial Office in London was not given until February 1906, the Governor, Sir Matthew Nathan, had anticipated a positive outcome and had already instructed the Public Works Department to start earthworks on the route from Tai Po Market to Fanling in December 1905.

The initial estimate for the project was HK$5,053,274, which included the cost of excavating a tunnel through the Kowloon hills at Beacon Hill and reclamation in Kowloon for a terminus. However, due to underestimating the problems to be overcome, changes in design, the fall of the value of the HK dollar to the pound sterling (much of the equipment had to be imported from Britain), difficulties in recruiting suitable labour coupled with a high mortality and sickness rate amongst the workers (malaria, beri beri and dysentery were endemic in Hong Kong at that time) and right-of-way land acquisition costs led to the final cost of the project to steadily rise over the construction period.

The most difficult part of the project was the construction of the Beacon Hill Tunnel, which ended up costing about one quarter of the whole project. Together with the construction of a two-foot narrow gauge branch railway from Fanling to Sha Tau Kok (making use of the rails and rolling stock used in the construction of the main line and later closed in April 1928), the final cost was HK$12,296,929, making it one of the most expensive railways in the world and, as costs escalated, the subject of much concern in both Hong Kong and London.

Although the design called for the construction of only a single track of a standard gauge of 4 feet 8½ inches, an important decision made was to ensure that as far as possible the bridges, cuttings, embankments and tunnels, with the exception of the Beacon Hill Tunnel, allowed for the laying of a future second track. This decision, although it might have seemed unnecessarily costly at the time, proved of benefit some 75 years later when the railway was finally double-tracked.

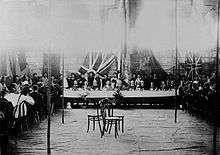

The railway was formally opened on Saturday, 1 October 1910, but without a terminus, this event being officially recorded by way of a notice in the following Friday's Hong Kong Government Gazette.

Opening Ceremony at Tsim Sha Tsui on 1 October 1910

Opening Ceremony at Tsim Sha Tsui on 1 October 1910 Original route of KCR line in Kowloon

Original route of KCR line in Kowloon Acting Governor, Sir Henry May, and his wife inspect the tracks of the British Section at Lo Wu on 1 October 1910

Acting Governor, Sir Henry May, and his wife inspect the tracks of the British Section at Lo Wu on 1 October 1910 Acting Governor, Sir Henry May, and guests at Lo Wu on 1 October 1910

Acting Governor, Sir Henry May, and guests at Lo Wu on 1 October 1910

Some 39 acres (16 ha) of the harbour at the south of the Kowloon peninsula, between Signal Hill (Blackhead Point) and Hung Hom, had taken place using material excavated from the route and carried to the site by a two-foot gauge railway. However, the final decision to locate the terminus at the tip of Kowloon peninsula was not made until 1910, and the terminus was only fully completed and commissioned in March 1916, although the platforms themselves were put into service in 1914.[3]

The railway opened in 1910 with a number of temporary stations. Part of a godown (warehouse) next to the site of the present day Star Ferry pier in Tsim Sha Tsui was rented and converted into a passenger station with rails to it laid down Salisbury Road from Signal Hill. Temporary stations were erected at Hung Hom and Lo Wu, with permanent stations being built at Sha Tin and Tai Po (later called Tai Po Kau), and a flag station at Tai Po Market.

Traffic on the new railway was at first quiet as there was little demand for passenger and freight services by the inhabitants of the then undeveloped New Territories north of Beacon Hill. Only after the Chinese Section was completed and opened in 1911 did traffic start to build up as people took advantage of the fast journey time of only 3 hours 40 minutes from Kowloon to Canton.

Little changed up until the Second World War, with the commercial success of the railway being closely linked to events in China. During the defence of Hong Kong in December 1941, various bridges and tunnels were deliberately blown up by the retreating British forces. After repairs had been made, the line was operated throughout the war by the Japanese using the services of the Chinese staff who had remained after the fall of the colony. During this period the railway gradually deteriorated through lack of adequate maintenance. Rolling stock and other equipment were also sent to China for use there by the Japanese.

After the British resumed control of Hong Kong in 1945, following the defeat of Japan, the railway was in a sorry state. Initially the task of restoring the railway to a working condition rested with the military. Twelve locomotives were urgently ordered from Britain (arriving in 1946–47) and efforts focussed on bringing the railway up to a workable condition. Civilian management of the railway was again resumed in 1946.

The post-war management faced many problems, including lack of records which had almost all been destroyed by the Japanese and had to be reconstructed from the memories of serving and previous staff; shortages of coal for the engines necessitating their conversion to burning fuel oil; currency exchange rate difficulties due to devaluation of the Chinese currency requiring agreement with the Chinese authorities to use the Hong Kong dollar as the basis for all transactions; worn out equipment and staff shortages. At the same time, there was a huge demand for passenger and freight services as people who had fled to China during the war moved back to Hong Kong, and because huge volumes of goods needed to be carried into China to help in post-war relief efforts there. From an immediate post-war figure of around 600,000, the population of Hong Kong rose to nearly 2 million by the end of 1947, with the influx reaching a rate of about 100,000 per month during this period.

Although freight demand to China gradually fell, the influx of people from China continued due to the civil war between the Communists and Nationalists. Through-train passenger services to China stopped on 14 October 1949, the day prior to the capture of Canton by the Communists. Passengers and goods then had to be transhipped at the border. Despite the inconvenience that this caused, the railway benefitted by Hong Kong becoming the centre of communications and trade with southern China, especially as much of the traffic that had hitherto gone by sea could no longer do so. Refugees fleeing the new communist government of China also often settled in squatter areas along the railway and this together with an increase in the British Army's presence added to domestic travel demand in Hong Kong.

In 1951 agreement was reached with the Chinese authorities for goods wagons to again cross the border, but passenger services continued to terminate at the border at Lo Wu station. However, the Korean war (1950–1953) led to an embargo by western governments on certain goods being exported to China, and tough restrictions introduced by the Chinese government on the number of people allowed to cross the border, which together led to a severe decline in rail revenue.

The situation saw little improvement until 1955, and to reduce the operating costs of the steam locomotives a decision was taken in 1954 to gradually replace these with diesel locomotives. For the rest of the 1950s and 1960s, despite some short-term disturbances in 1967 resulting from a spill over into Hong Kong of the Cultural Revolution in China, both domestic and cross-border traffic continued to show steady overall growth.

One major decision taken during the late 1960s was to relocate the large railway workshops from Hung Hom to their present location at Ho Tung Lau in Sha Tin and to construct a new terminus at Hung Hom. This was necessary to permit construction of the first cross harbour road tunnel, replacing the previously reliance on ferries to cross the harbour from Kowloon to Hong Kong Island, and to overcome the constraints imposed on rail traffic growth by the first terminus at Tsim Sha Tsui. While the move to Ho Tung Lau took place in 1968, the Hung Hom Terminus complex was not completed and opened until November 1975, at which time the Tsim Sha Tsui Terminus was closed and shortly thereafter demolished except for the clock tower, which remains a landmark today.

So far improvements to the railway had been incremental in nature. In the 1970s it became clear that a radical rethink was needed if the railway was to cope with future demands. In 1972 the government set up a steering group to examine the need for future short-term and long-term improvements to the railway given the growth in freight and passenger traffic to China, coupled with the government's plans to construct large new towns at Sha Tin, Tai Po, Sheung Shui and Fanling in the New Territories that would further increase domestic travel demand.

At that time the new towns were intended to be constructed to a "balanced design" concept under which employment opportunities as well as people would be relocated from substandard accommodation in the older urban areas, thereby minimising the additional demand on the transport network. As later became apparent, however, while people were moved in their hundreds of thousands to live in the New Territories, the major centres of employment and of leisure activities remained in the urban areas, leading to an even greater dependence on the railway to support a rapidly increasing daily commuter flow.

In 1974 a 10-year investment programme was started to provide for the complete double-tracking and electrification of the railway from Hung Hom to Lo Wu, requiring the building of a second Beacon Hill Tunnel together with the construction or upgrading of stations and other facilities. This exercise was completed by the early 1980s and on 16 July 1983 the use of diesel-hauled trains ceased for domestic passenger services. Diesel locomotives continued to be used for through-train passenger services, which resumed in 1979 following implementation by Deng Xiao Ping of economic reforms in China, and for freight and track maintenance services.

One consequence of the electrification was that, whereas much of the old track in the New Territories had remained unfenced, with footpaths or roads alongside or across the track used by many villagers, the faster, quieter and more frequent electric services required the complete fencing off of the track from Lo Wu to Hung Hom, necessitating the construction of footbridges with both steps and sloping ramps at various village locations. As a former Assistant District Officer in Tai Po recalls, one of the claimed concerns of the villager elders at the time was to be able to carry coffins across the tracks to the nearest road as not all villages were served by an alternate road access.

During this 10-year period, thought had also been given by the government as to the future management of the railway. Hitherto the railway had been run as a department of the government, and was subject to the normal civil service rules and requirements. This made it difficult to take a commercial approach to operating what was increasingly becoming a major business in investment and revenue terms. Corporatisation of public services as a means to permit government-owned public utilities to operate more along the lines of private sector business was an approach that was beginning to gather interest at the time from several governments – the US and UK governments under Reagan and Thatcher being prime movers. The object of corporatisation was to allow the public service providers to make a commercial return on their assets, thus reducing the need for investment of public funds raised predominantly from taxes, while still remaining under government control.

On 24 December 1982, the KCRC Ordinance (Cap 372) was enacted and the KCR ceased to be a government department, although it remained wholly owned by the government. Under the Ordinance a managing board, comprising 10 members appointed by the governor (Chairman, managing director and not less than 4 nor more than 8 other members), became responsible for overseeing the day-to-day operations of the Corporation. The Corporation was required to "perform its functions with a view to achieving a rate of return on the assets employed in its undertaking, and in accordance with ordinary commercial criteria, is satisfactory."

An expanding network

The KCR expanded its operations starting in 1984. It accepted an invitation from the government to build and operate a light rail network in the north western New Territories serving the local public transport needs of the future residents of the Tuen Mun and Yuen Long new towns.

The first choice of operator for this network had not in fact been KCR, nor had the construction of a light rail network been decided when the plans for the new towns were first drawn up. Originally the focus had been on Tuen Mun, with the new town being planned from the outset with an 'exclusive public transport right of way' segregated from the ordinary road network.[4] In 1977 the government commissioned Scott Wilson Kirkpatrick & Partners, the engineering consultants for the Tuen Mun new town, to undertake the Tuen Mun Transport Study. This involved the evaluation of the respective merits and demerits of various modes of public transport to determine which would best meet the needs of the area.

The final selection came down to a choice of one of three systems – double-deck diesel powered buses, electrically powered trolley buses, and electrically powered light rail vehicles supported by diesel buses serving less densely populated areas or where steeper gradients limited the use of light rail vehicles. Diesel buses, although unquestionably more flexible in operation and requiring far lower initial capital costs, because they did not rely on fixed overhead power lines and tracks like trolley buses and light rail vehicles, were ruled out on grounds of air pollution.

Trolley buses were ruled out on grounds of capital costs, in that the purchase price of a trolley bus was twice that of a diesel bus but offered no greater passenger carrying capacity. They also offered less operational flexibility in that they required the provision of a fixed overhead power line. It was recognised, however, that a case for the use of trolley buses over diesel buses might made were the relative costs of diesel fuel versus electrical power to change.[5]

The consultants' final report of November 1978 recommended the construction of a light rail system. The consultants argued that a light rail system offered "the best technical and economic solution to the future travel needs of Tuen Mun. Such a system would, moreover, help to promote and develop the image of the new town." Light rail vehicles would offer greater passenger carrying capacity than buses, and, although initially more expensive to purchase than diesel or trolley buses, their economic life of around 50 years was far longer than that for diesel and trolley buses of around 15 years. The consultants estimated that over 30 years the light rail system would provide an 8% return on assets assuming an annual discount rate of 15% and an annual inflation rate of 7%. The study finally also recommended the extension of the light railway system to the Yuen Long new town.

The consultants proposed the use of double deck trams each carrying 247 passengers (diesel buses then in operation could each only carry about half that number).[6] The use of single deck trams was ruled out on the grounds of capital cost because of the need to purchase a larger number of vehicles to provide the same total passenger carrying capacity for the system. It would later transpire that no light rail vehicle manufacturer could offer such double deck vehicles and none were prepared to invest in the manufacturing capacity needed to build such vehicles given the relatively small number required. Ultimately single deck vehicles had to be ordered, which although longer at 20.2 metres, can only achieve a similar maximum passenger capacity of around 238 passengers by having all but 26 passengers standing.

| Capital Cost Comparison of Different Systems Based on 15 km of Light Rail Track Plus 10 km of Bus Feeder Routes | Capital Cost (HK$ million) |

| Diesel buses | 60 |

| Trolley buses | 109 |

| Double-deck light rail | 164 |

| Single-deck light rail | 266 |

| Source: Tuen Mun Transport Study 1978, Volume 1 | |

These recommendations came at the same time as the government was examining proposals for a mass transit system along the north of Hong Kong Island. As explained by the Secretary for Transport in the Legislative Council on 5 July 1978, the government had asked the then Mass Transit Railway Corporation (MTRC) to plan the construction of a mass transit light rail system on HK Island more or less along the alignment of Hong Kong Tramways' existing line, which had been in operation since 1904 and lacked the capacity to handle anticipated future public transport demands. If MTRC's plan was viable, the government would exercise its option under Section 30 of Tramways Ordinance to buy out the existing tramway operation.

Section 30 of the Ordinance required the government to acquire Hong Kong Tramways' land and assets at their full market value. In exchange for the surrender of the Hong Kong Tramways' Hong Kong Island operations, the government indicated its willingness to offer the right to operate the future Tuen Mun light rail system to the company. However, in January 1983 the government announced that it had not been able to reach an agreement with the Kowloon Wharf and Godown Company (the owner of the Hong Kong Tramways). The main sticking points in the negotiations appear to have been the amount of profit that the company would have been allowed to earn from the Tuen Mun light rail network and the granting of property development rights.[7][8] Also during this time, the decision had been taken to construct the MTR Island line underground as had been the case with the MTRC's earlier Kwun Tong line.

Subsequent discussions with other possible interested parties also failed and in 1984 the government turned to the KCRC to invite it to take on the construction and operation of the light rail network.

The Light Rail Transit (LRT, known later as the KCR Light Rail and currently simply as the Light Rail) came into service in September 1988. Although the system was generally successful in meeting passenger demand, it was never a commercial success. According to the corporation's annual reports, the system showed an annual cash-operating loss up to 2003.[9]

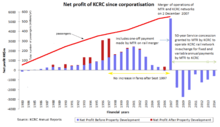

The KCRC started to participate in property development and management at around the same time as constructing Light Rail. The first joint-venture property development, Pierhead Garden, located above a light rail and bus terminus in Tuen Mun, was completed in 1988. While profits generated from property and commercial services were useful to fund new railway projects, they were never regarded as essential, being generally treated as a useful windfall. The chairman of the KCRC, K Y Yeung, highlighted this in his statement made in the 2002 annual report, by pointing out that "our main source or revenue has always been and will continue to be fares. The receipts from property developments are one-off in nature and are not a dependable, long-term source of revenue for the Corporation."

In 1994 the government published its Railway Development Strategy, which identified the need for a railway to serve the rapidly expanding new towns in the northwestern New Territories. In October 1998 KCR began work on the construction of an entirely new line of some 30.5 km in length, connecting the new towns of Yuen Long, Tin Shui Wai and Tuen Mun with urban Kowloon. Originally estimated to cost HK$64 billion, the government agreed to make an equity injection of HK$29 billion to assist the corporation, with the remaining funds coming either from the corporation's own reserves or through borrowings in the open market. In return the corporation agreed to undertake property development along the line, the profits from which (then estimated to be in excess of HK$20 billion) being returned to the government.[10]

The government also enacted an amendment to the KCR Ordinance in 1998. The purpose of the amendment was to enable the corporation to build new railway projects (other than East Rail and Light Rail) and to raise commercial loans. Also included in the amendment was the removal of the requirement on the corporation to make a return on its fixed assets. This was particularly important as it was recognised that the heavy capital investment in new railways would not enable the corporation to make a commercial return for a good number of years on what would become a far larger asset holding. The basic requirement now placed on the corporation was that. "The Corporation shall conduct its business according to prudent commercial principles and shall ensure as far as possible that, taking one year with another, its revenue is at least sufficient to meet its expenditure."[11]

The KCR West Rail (now the West Rail Line on the MTR network) was finally opened on 20 December 2003. As a result of extensive value engineering exercises, the final cost of the project came in much lower than originally forecast at HK$46.6 billion.

.png)

The following year two extensions to the East Rail network were commissioned, both lines also forming part of the government's Railway Development Strategy. In October 2004 the KCR East Rail (now the East Rail Line on the MTR network) was extended from Hung Hom Station to East Tsim Sha Tsui Station, enabling KCR services to return to a location close to the original 1910 KCR terminus. In December 2004 Ma On Shan Rail (now the Ma On Shan Line on the MTR network) was opened, linking Wu Kai Sha with East Rail at Tai Wai Station. Some three years later, in August 2007, a third extension, the Lok Ma Chau Spur Line came into service. Extending from East Rail at Sheung Shui to a second cross-boundary terminal at Lok Ma Chau, the Spur Line was intended to alleviate congestion for cross-boundary travellers at the existing Lo Wu terminal and to provide a convenient connection to the Shenzhen Metro system.

In 2000 the government published its updated Railway Development Strategy. Included was a proposal by KCR to construct a 3.8 km extension to the West Rail line from Nam Cheong Station to East Tsim Sha Tsui Station, with the existing section of East Rail line from Hung Hom Station to East Tsim Sha Tsui Station being modified to become part of the extended West Rail line. Known as the Kowloon Southern Link (KSL), the extension, with a new intermediate station at Austin Road, was completed and opened for passenger services on 16 August 2009.

The financial impact of all these new projects can be seen in the declining net profits of the corporation from 2001. Despite increasing passengers, heavy interest expenses on borrowings and depreciation charges on the new assets pushed net profits down to close to zero by the end of 2007. However, if non-cash depreciation charges are excluded, which rose from about HK$700 million in 2001 to HK$2,400 million by 2007, the corporation continued to show a cash operating profit.

Of interest also is that the last fare increase made by the corporation was in 1997.[12] Although proposals were put forward to increase fares over the subsequent 10 years to provide comfort that the corporation would be able to service its increasing debt portfolio created by the need to fund the expansion of the KCR network, these came to naught in light of economic and political pressures. The chairman and chief executive, K.Y. Yeung, most eloquently explained the "catch-22" situation faced by the corporation in his statement contained in the 2001 annual report.

"While the Corporation has autonomy to decide fares, we face the classic dilemma of most publicly owned transport operators when it comes to raising fares. On the one hand, in the current period of economic deflation, there is considerable pressure on public transport operators not to increase fares so as to share the burden of the community. On the other hand, when inflation returns, there will be equal pressure on operators to keep any fare increases below the rate of inflation so as not to fuel inflation.

The longer term implications of this dilemma for the Corporation are obvious. A way has to be found out of this situation if we are to fund new projects. We must try to devise a consistent policy in respect of fare increases which will allow us to demonstrate to investors that we can generate the necessary stable revenue stream in the medium to long term and which, at the same time, will also allow us to demonstrate to our passengers that our fares will remain competitive with those of alternative modes of public transport."[13]

Of critical concern to the corporation was the gradual erosion of its cross-boundary market, where for many years it had enjoyed the majority share and was able charge a fare premium. The corporation faced increasing competition from road transport operators, mainly coach operators, following the opening of a number of major crossing points providing convenient road access to Shenzhen and southern China. Profits from this segment of the corporation's transport operations were considered vital to subsidise its domestic services which in general operated at a loss.[14]

Ceased to be a public transport operator

During the construction of the KSL, KCRC ceased to be a public transport operator. The government's Railway Development Strategy 2000 proposed the construction of a new line to link up the northeastern New Territories and the central business area of Hong Kong Island, to be called the Sha Tin to Central Link (SCL). Competitive proposals were invited from both KCRC and the MTR Corporation Limited (MTRCL) to design, build and operate the new line. On 25 June 2002 the government announced that KCRC had won the bid. In the same announcement the government said that, as a separate issue, the chief executive in Council had also instructed the Administration to consider the feasibility of merging the MTRCL and the KCRC into a single rail company.[15]

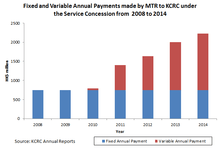

Following five years of negotiations and the enactment of the Rail Merger Ordinance after its passage through the Legislative Council, the KCRC ceased to be a public transport operator on 2 December 2007, becoming thereafter primarily simply the holder of railway assets. Instead of being the operator of those assets, KCRC granted MTRCL the right to operate KCRC's rail and feeder bus network under a service concession agreement for an initial period of 50 years, which may be extended. In return MTRCL was required to make an upfront payment to KCRC of HK$4.25 billion for the service concession and certain short-lived railway assets of KCRC such as stores and spares, and thereafter a fixed annual payment of HK$750 million and, commencing 36 months after the date of the merger (i.e. 2 December 2010), an additional variable annual payment calculated according to a pre-agreed set of sharing ratios as follows –

- 10% for gross revenue earned by MTRCL from the KCRC railway assets exceeding HK$2.5 billion and up to HK$5 billion for the year;

- 15% for gross revenue between HK$5 billion and HK$7.5 billion for the year; and

- 35% for gross revenue beyond HK$7.5 billion for the year.

MTRCL also paid KCRC HK$7.79 billion on the merger for the acquisition of property and other related commercial interests.[16]

KCRC and MTRCL remain as separate entities. KCRC employs a small number of management staff answerable to its Managing Board, with specialist legal, financial and other support being provided through outsourcing and consultancy arrangements. The Corporation's key responsibilities include overseeing and fulfilling its obligations with respect to its service concession with the MTRCL, raising new financing as needed to service its debts (over HK$10 billion was raised in 2009), ensuring compliance with its obligations under a number of cross-border leases covering its rolling stock and other assets, and being the majority shareholder for West Rail Property Development Limited, which is responsible for the development of some 13 residential property sites along West Rail. In addition to the revenue earned from the concession payments made by the MTRCL, it earns rental revenue from leasing out four floors of Citylink Plaza above Shatin Station.[17]KCRC also retains a 22.1% shareholding in Octopus Holdings Limited (OHL), which was first established in 2005 and is owned by the major public transport operators in Hong Kong. OHL is the holding company of Octopus Cards Limited, which is a world leader in smart card payment systems used not only for making public transport journeys within Hong Kong but also for making small purchases in supermarkets and other convenience stores.

KCRC also remained responsible for funding the full construction costs of the KSL, which was under construction at the time of the merger, with the MTRCL paid a fee for project managing the works. KCRC also funded the purchase of 22 additional light rail vehicles needed to accommodate the increase in patronage expected on light rail feeder routes to West Rail stations as a result of the opening of the KSL. MTRCL assumed responsibility for operating the KSL and the new light rail vehicles under the service concession.

Although the corporation's annual revenues saw a sharp decline from over HK$5.5 billion before the merger to less than HK$1 billion immediately after the merger, its operating costs similarly declined. The corporation was also fortunate in being able to refinance a substantial portion of its large debt portfolio during the low interest environment that prevailed during 2009 and 2010. This reduced the corporation's interest costs by more than half because the effective interest rate on its debt fell from above 7% to around 3%.[18] Excluding non-cash depreciation charges, the corporation enjoys a cash operating profit, which should continue to increase over time as reflected in MTRCL's variable annual payments.

The variable annual payment for 2010 was HK$45 million, covering the period from 2 to 31 December 2010 only. For the first full year of 2011 the variable annual payment was HK$647 million. By 2013 the annual variable payment had increased to HK$1,247 million. With the HK$750 million fixed annual payment, the total cash payment made by MTRCL under the Service Concession for 2013 was HK$1.997 billion.[19]

Plans

After the announcement in June 2002 that KCRC had won the bid to design, build and operate the SCL, the corporation proceeded with detailed planning for the project. In 2005, however, work was suspended pending an announcement by the Government of its decision on how and by whom the SCL would in fact be constructed. By this time KCRC had incurred some HK$1.188 billion in costs on the project.[20]

Following the rail merger, the government took over responsibility for the project. According to the government's latest plan as explained to the Legislative Council in March 2008, the cost of building the SCL will be borne by the government, with MTRCL given responsibility for managing the design and construction of the line. The government has indicated that it may vest the completed line in, or lease the line to, KCRC, which would then grant an additional service concession to the MTRCL to operate the line. KCRC has indicated that such an arrangement would enable recovery of the corporation's earlier costs on the project.[21]

Chairmen, managing directors, chief executive officers and chief officers since corporatisation

| 1983 | |

| H M G Forsgate | Chairman |

| D M Howes | MD (until 18 December) |

| P V Quick | MD (from 19 December) |

| 1984 to 1989 | |

| H M G Forsgate | Chairman |

| P V Quick | MD |

| 1990 | |

| H M G Forsgate | Chairman (until 23 December) |

| P V Quick | MD (until 31 August) |

| Kevin O Hyde | Chairman and chief executive (from 24 December) |

| 1991 to 1995 | |

| Kevin O Hyde | Chairman and chief executive |

| 1996 | |

| Kevin O Hyde | Chairman and chief executive (until 23 December) |

| K Y Yeung | Chairman and chief executive (from 24 December) |

| 1997 to 2000 | |

| K Y Yeung | Chairman and chief executive |

| 2001 | |

| K Y Yeung | Chairman and chief executive (until 23 December) |

| Michael Tien | Chairman (from 24 December) |

| K Y Yeung | Chief executive officer (from 24 December) |

| 2002 and 2003 | |

| Michael Tien | Chairman |

| K Y Yeung | Chief executive officer |

| 2004 and 2005 | |

| Michael Tien | Chairman |

| Samuel Lai | Acting chief executive officer |

| 2006 | |

| Michael Tien | Chairman |

| Samuel Lai | Acting chief executive officer (until 30 April) |

| James Blake | Chief executive officer (from 1 May) |

| 2007 | |

| Michael Tien | Chairman (until 1 December) |

| James Blake | Chief executive officer (until 1 December) |

| Prof K C Chan | Chairman (from 2 December) |

| James Blake | Chief officer (from 2 December) |

| 2008 to 2012 | |

| Prof K C Chan | Chairman |

| James Blake | Chief officer |

| 2013 to present | |

| Prof K C Chan | Chairman |

| Edmund K H Leung | Chief officer |

Corporate governance

From corporatisation in December 1982 until the rail merger 25 years later, corporate governance issues periodically troubled the corporation. Reflecting this were the changes that took place in the relationship between the chairman of the managing board and the head of the executive management team.

Initially the root causes of this were the commercial and political tensions arising from the change from a government department to an organisation expected to operate in a prudent commercial manner so as to make a return on its fixed assets. While expected to make a profit to comply with its mandate under the KCRC Ordinance, because the corporation remained 100% government owned, it faced at the same time strong public and political pressure not to increase fares. These difficulties were further complicated by corporate governance issues involving senior management and members of the corporation's managing board.

At corporatisation the positions of (non-executive) chairman of the managing board and that of the (executive) managing director were separate, with the managing director answerable to the board for the day-to-day business of the corporation. D M (Bobby) Howes, the previous general manager of KCR remained for a few months until his successor, Peter Quick, took up the post. Unlike Howes, who was a traditional railway man, Quick came from a commercial background, and from the outset, adopted a strong commercial approach to the operation of the railway. His efforts were reflected in the gradually increasing profitability of the corporation.[22]

However, as a result of public controversy in late 1988 over claimed "golden handshakes" paid to two senior executives as a result of termination of their services, and in 1989 a fare increase with the corporation already enjoying a significant profit, the government took the decision that both the chairman and the managing director should leave upon expiry of their period of office.[23][24]

At the end of 1990, with the appointment of Kevin Hyde, a Lawyer and the former chief executive of New Zealand Railways Corporation, the two formerly separate positions were combined into the single position of chairman and chief executive. During his tenure, Hyde oversaw unprecedented growth in the business as well as spearheading a number of significant commercial and engineering projects, including the West Rail Project. Hyde forged new and productive working relationships with the KCRC's Mainland counterparts and Ministry Officials leading to a number of co-operative projects on both sides of the border. He also introduced a 'post-colonial' ethos within the business, actively developing and promoting local executives and expertise. Hyde left in 1996 having decided that it was important that the business entered the 1997 handover with a local person in the position of chairman and chief executive.

He was replaced by K Y Yeung, a former senior civil servant with the Hong Kong government. While the KCRC continued to prosper financially, K Y Yeung’s style of management, founded as it was in his civil service background, did not sit well with some.[25]

In December 2001 the government enacted an amendment to the KCRC Ordinance to provide for the separation of the functions and duties of the chairman from those of the chief executive by creating the office of chief executive officer (CEO), who also became a member of the managing board. The government argued that, with the then planned expansion of the railway network, there was a growing need to separate the strategic planning functions and day-to-day management responsibilities of KCRC. Enacting legislation to separate the functions and duties of the chairman and the CEO was intended to put in place an effective governance structure to ensure transparency, accountability and responsibility. By strengthening the independence of the KCRC board and providing clear lines of reporting, there would be improved checks and balances over senior management.[26]

Unfortunately, as set out in a paper by the legal adviser to Hong Kong’s Legislative Council, the amendments did not spell out in detail the duties and functions of the chairman and the CEO, or at least their responsibilities. The government argued that this would not be appropriate as it was important for KCRC, which operated along prudent commercial principles, to retain the flexibility to determine and fine-tune the relationship between the managing board (led by the chairman) and the executives (led by the CEO) to suit its operational needs and the prevailing corporate practices which change over time.[27] This deliberate lack of clarity arguably sowed the seed for a future controversy.

Michael Tien, a businessman, was subsequently appointed as the chairman, with the former chairman and chief executive, K Y Yeung, stepping down to become the CEO. It rapidly became publicly evident, however, that there was personal tension between the two, exemplified by Michael Tien's denial that he was a good friend of K Y Yeung when the two briefed the media in 2002 on the findings of the investigation into the Siemens incident. (The investigation dealt with the payment of an additional HK$100 million to Siemens under a supplementary agreement to the telecommunications contract for the West Rail project, and the interaction between the managing board and the executive management team.)[28]

The situation did not improve with K Y Yeung’s departure at the end of 2003, following the opening of West Rail. At the heart of the problem was the lack of clarity in the respective roles and responsibilities of the chairman and the CEO. On 9 March 2006, with the signed support of all 5 operations directors and 19 managers, the Acting chief executive officer, Samuel Lai, wrote to the Managing Board to complain about the leadership style of the chairman. Around 80% of the staff signed in support of Lai. In Lai's letter he stated that little had changed since 2001, and that the necessary distinctions between the different but complementary roles of the executive and non-executive functions frequently became blurred, with the chairman interfering in how day-today matters should be handled.[29]

On the following day, Michael Tien met the chief executive of Hong Kong, Donald Tsang. In the afternoon of 12 March 2006, Tien announced his resignation, with the effective date to be determined by Tsang. After further negotiation, Tien withdrew his resignation. The KCRC managing board convened a meeting on 14 March 2006 and decided on a set of measures to more clearly delineate the work of the chairman and CEO.

While the board meeting was being held, 20 of the corporation's senior executives met the media in a room next to where the board meeting was being held. The managing board considered this to be a very serious matter, and that the incident had caused serious damage to the reputation and image of the corporation. A further meeting of the board was held the next day on 15 March 2006. The board decided to terminate the employment contract of one of the 20 senior executives and to issue warning letters to the remaining 19. At the meeting Lai resigned. The reason given in the government's paper to the Legislative Council's Panel on Transport was because Lai, being the CEO, felt that he should be held responsible for the acts of his staff.[30] Lai, in the personal account given in his book published in 2007 (九天風雲 (English title: The Longest Week)), explained that the original decision of the board had been to sack all 20 senior executives, but by his offering to resign, the board had agreed to dismiss only the senior executive who had acted as the spokesman for the 20 on 14 March.

A civil engineer, James Blake, the former Secretary for Works in the Hong Kong Government and afterwards the Senior Director Projects of the corporation until the end of 2003, took over as the chief executive officer (not acting) at age 71. The incident was seen to have sped up the government's plan to merge the operations of Hong Kong's two railway networks. Lai in his book states that at the board meeting held on 15 March 2006, the first item on the agenda was the appointment of Blake as the deputy CEO responsible for the proposed rail merger, which was raised by the then Secretary for Financial Services and the Treasury on behalf of the government as the sole shareholder of the corporation. The appointment was unanimously approved. With Lai's resignation, the board had then decided to invite Blake to become the CEO.[31] Lai agreed to stay with the corporation for a while longer to ensure a smooth handover to Blake.

Thereafter matters moved fairly swiftly on the merger, resulting in the corporation finally ceasing to be the operator of its railway assets on 2 December 2007.

Until the rail merger, the KCRC Ordinance had required that the corporation appoint a CEO. As part of the Rail Merger Ordinance an amendment was made to the KCRC Ordinance to provide for the post of the CEO to be left vacant should the corporation so decide. On the merger the decision was taken not to fill the post and instead Mr. James Blake, the former CEO, was appointed as the Chief Officer to head the small management team.[32] The composition of the managing board also changed, the number of members being reduced from 10 (of whom only two were government officials) to six (all of whom are government officials), with the chairman of the board being the Secretary for Financial Services and the Treasury.

See also

- MTR Corporation

- Transportation in Hong Kong

- List of Hong Kong companies

- List of Chinese companies

- Guangzhou–Shenzhen Railway

- Shenzhen Metro

References

- ↑ LC Paper No. CB(1)1291/05-06(01). Legislative Council Panels on Transport and Financial Affairs. Merger of MTR and Kowloon–Canton Railway Systems – Proposed Way Forward, 11 April 2006

- ↑ Kowloon–Canton Railway (British Section) – A History, Robert J Phillips, An Urban Council Publication, 1990

- ↑ Kowloon–Canton Railway (British Section) Annual Reports for 1914 to 1916

- ↑ Minutes of the Legislative Council meeting of 16 July 1986

- ↑ The case for adopting trolley buses might be stronger today given increased oil prices, and the considerable progress made over the past few years in battery, supercapacitor and hybrid power systems that allow trolley buses to partially free themselves from total dependence on fixed overhead power lines.

- ↑ The proposed vehicles were 16.5 metres long, seating 103 passengers on the upper deck, with 32 sitting and 112 standing passengers on the lower deck.

- ↑ South China Morning Post, 21 July 1982

- ↑ Minutes of Legislative Council Meeting of 2 February 1983

- ↑ In December 2003, the corporation introduced free light rail feeder services for those light rail passengers paying by Octopus Card who also made use of the new West Rail line for part of their journey. The free feeder service was intended to encourage use of the new line and to release light rail vehicles from the previous long-distance Tuen Mun to Yuen Long routes, which were now paralleled by West Rail, for reallocation to those more congested internal routes within the two new towns. With the total fare for the combined Light Rail plus West Rail journey now becoming simply the West Rail fare, and given the large number of Light Rail passengers taking such combined journeys, the corporation ceased to publish separate operating profit figures for Light Rail from the end of 2003.

- ↑ Paper for the Finance Committee of the Legislative Council FCR(97–98)97 dated 27 February 1998

- ↑ Kowloon–Canton Railway Corporation (Amendment) Ordinance 1998

- ↑ In fact all railway fares, except those of the Airport Express, cross-boundary trips to and from Lo Wu and Lok Ma Chau, intercity, Light Rail and the Ngong Ping 360, were reduced by a minimum of 10% on the rail merger in 2007 and were not increased again on the KCRC network until 2009, when the first adjustment was made under the Fare Adjustment Mechanism agreed at the time of the 2007 rail merger.

- ↑ This dilemma has since been addressed by the government in the form of the Fare Adjustment Mechanism agreed with MTR as part of the rail merger package, details of which are set out in the paper to the Legislative Council Panel on Transport, dated April 2011, LC Paper No. CB(1)1836/10-11(05)

- ↑ 2004 KCRC Annual Report – Chairman's Statement, page 13

- ↑ Hong Kong Government press release dated 25 June 2002

- ↑ LC Paper No. CB(1)1291/05-06(01) issued on 11 April 2006

- ↑ KCRC Annual Report 2009

- ↑ 2009 and 2010 KCRC Annual Reports

- ↑ 2013 KCRC Annual Report

- ↑ 2005 KCRC Annual Report

- ↑ 2009 KCRC Annual Report

- ↑ A Century of Commitment – the KCRC Story

- ↑ Hiving off: the case of the Kowloon–Canton Railway Corporation, Emily Leung Pik-yee, June 1989, HKU http://hdl.handle.net/10722/28310

- ↑ Moving millions: the commercial success and political controversies of Hong Kong’s railways, Ricky Yeung, HK University Press, 2008

- ↑ Moving millions: the commercial success and political controversies of Hong Kong’s railways, Ricky Yeung, HK University Press, 2008

- ↑ Deliberations of the Legislative Council’s Bills Committee on Kowloon–Canton Railway Corporation (Amendment) Bill 2001

- ↑ Paper for the House Committee meeting of the Legislative Council on 2 November 2001 (LC Paper No LS2/01-02)

- ↑ http://www.legco.gov.hk/yr01-02/english/panels/tp/tp_rdp/papers/tp_rdp0516report.pdf

- ↑ 九天風雲 (English title: The Longest Week) by 黎文熹 (Mr. Samuel Lai Man-hay), Joyful Books Ltd., 2007 (Chinese language only)

- ↑ LC Paper No CB(1)1131/05-06(01) of March 2006

- ↑ LC Paper No.CB(1)1083/05-06 of March 2006

- ↑ 2008 KCRC Annual Report

External links

- Official website of the Kowloon–Canton Railway Corporation

- 踩場九鐵經理勢受處分 – 明報通識網LIFE

- Paper for LegCo Panel on Transport on 21 March 2006 dealing with KCRC Corporate Governance – EnglishChinese

- 頭條日報頭條網- 九天英雄黎文熹