List of commercial failures in video gaming

As a hit-driven business, the great majority of the video games industry's software releases have been commercial failures. In the early 21st century, industry commentators made these general estimates: 10% of published games generated 90% of revenue;[1] that around 3% of PC games and 15% of console games have global sales of 100,000+ a year, with even this level insufficient to make high-budget titles profitable;[2] and that about 20% of games make a profit.[3]

Some of these have drastically changed the video game market since its birth in the late 1970s. For example, the failures of E.T. and Pac-Man for the Atari 2600 contributed to the video game crash of 1983. Some games, despite being commercial failures, are well received by certain groups of gamers and are considered cult games. Many of these games live on through emulation.

Video game hardware failures

A commercial failure for a video game hardware platform is generally defined as a system that either fails to become adopted by a significant portion of the gaming marketplace or fails to win significant mindshare of the target audience, and may be characterized by significantly poor international sales and general financial unviability of development or support.

3DO Interactive Multiplayer

Co-designed by R. J. Mical and the team behind the Amiga, and marketed by Electronic Arts founder Trip Hawkins, this "multimedia machine" released in 1993 was marketed as a family entertainment device and not just a video game console. Though it supported a vast library of games including many exceptional third party releases,[4] a refusal to reduce pricing until almost the end of the product's life (699.95 USD at release) hampered sales. The success of subsequent next generation systems led to the platform's demise and the company's exit from the hardware market.[5] This exit also included The 3DO Company's sale of the platform's successor, the M2, to its investor Matsushita.[6]

Amstrad GX4000 and Amstrad CPC+ range

In 1990, Amstrad attempted to enter the console gaming market with hardware based on its successful Amstrad CPC range but also capable of playing cartridge-based games with improved graphics and sound. This comprised the Amstrad CPC+ computers, including the same features as the existing CPCs, and the dedicated GX4000 console. However, only a few months later the Mega Drive, a much-anticipated 16-bit console, was released in Europe, and the GX4000's aging 8-bit technology proved unable to compete. Many of the games were also direct ports of existing CPC games (available more cheaply on tape or disc) with few if any graphical improvements. Fewer than thirty games were released on cartridge, and the GX4000's failure ended Amstrad's involvement in the gaming industry. The CPC+ range fared little better, as 8-bit computers had been all but superseded by similarly priced 16-bit machines such as the Amiga, though software hacks now make the advanced console graphics and sound accessible to users.[7]

Apple Bandai Pippin

Pippin is a game console designed by Apple Computer and produced by Bandai (now Bandai Namco) in the mid-1990s based around a PowerPC 603e processor and the Mac OS. It featured a 4x CD-ROM drive and a video output that could connect to a standard television monitor. Apple intended to license the technology to third parties; however, only two companies signed on, Bandai and Katz Media,[8] while the only Pippin license to release a product to market was Bandai's. By the time the Bandai Pippin was released (1995 in Japan, 1996 in the United States), the market was already dominated by the Nintendo 64 and PlayStation,. The Bandai Pippin also cost US$599 on launch, more expensive than the competition. Total sales were only around 30,000 units.[9]

Atari 5200

The Atari 5200 was created as the successor to the highly successful Atari 2600. Reasons for the console's poor reception include that most of the games were simply enhanced versions of those played on its predecessor,[10] as well the awkward control design. The console sold only a little over a million units.[11] When it was discontinued, its predecessor would be marketed for several more years. The failure of the Atari 5200 marked the beginning of Atari's fall in the console business.

Atari 7800

Successor to the Atari 5200, and fully backwards compatible with the Atari 2600, this system failed despite getting mixed reviews from critics, and due to its graphic design and sound, it failed to get the same amount of attention from its competitors, Nintendo Entertainment System and Sega Master System

Atari Jaguar

Released by Atari Corporation in 1993, this 64-bit system was more powerful than its contemporaries, the Genesis and the Super NES (hence its "Do the Math" slogan); however, its sales were hurt by a lack of software and a number of crippling business practices on the part of Atari senior management. The controller was widely criticized as being too big and unwieldy, with a baffling number of buttons. The system never attained critical mass in the market before the release of the PlayStation and Sega Saturn, and without strong leadership to drive a recovery, it failed and brought the company down with it.[12][13] Rob Bricken of Topless Robot described the Jaguar as "an unfortunate system, beleaguered by software droughts, rushed releases, and a lot of terrible, terrible games."[14]

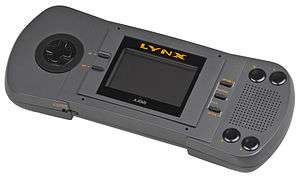

Atari Lynx

Released in 1989 in North America and Europe; later in Japan in 1990 by Atari Corporation, The Lynx is an 8 bit handheld game console that holds the distinction of being the world's first handheld electronic game with a color LCD. The Lynx was the second handheld game system to be released with the Atari name. The system was originally developed by Epyx as the Handy Game.[15] The system is also notable for its forward-looking features, advanced graphics, and ambidextrous layout.[16] In late 1991, it was reported that Atari sales estimates were about 800,000, which Atari claimed was within their expected projections.[17] Lifetime sales by 1995 amounted to fewer than 7 million units when combined with the Game Gear.[18] In comparison, the Game Boy sold 16 million units by later that year.[18] Around that time, Atari Corp. shifted its focus away from the Lynx. Overall lifetime sales were confirmed as being in the region of 3 million, a commercial failure despite positive critical reviews. In 1996, Atari Corporation collapsed due to the failures of the Lynx and Jaguar consoles.[19]

Bally Astrocade

The Bally Astrocade is a second generation console created by Bally. It was released in 1977 but only through mail order. Due to weak sales, Bally quit the console business. Shortly afterward, another company purchased the rights to the console, and rereleased it but to weak sales again.

Commodore 64 Games System

Released only in Europe in 1990 and being Commodore International's first venture in the video game market, the C64GS was basically a Commodore 64 redesigned as a cartridge-based console. Aside from some hardware issues, the console did not get much attention from the public, who preferred to buy the cheaper original computer that had far more possibilities. Also, the console appeared just as the 16-bit era was starting, which left no chance for it to succeed as it was unable to compete with consoles like the Super Nintendo Entertainment System and Mega Drive.[20]

Commodore CDTV

The CDTV was launched by Commodore in 1991. In common with the Philips CD-i and the 3DO, the CDTV was intended as an all-in-one home multimedia appliance that would play games, music, movies, and other interactive content. The name was short for "Commodore Dynamic Total Vision". The hardware was based on the Amiga computer with a single-speed CD-ROM drive rather than a floppy disk drive, in a case that was designed to integrate unobtrusively with a home entertainment center. However, the expected market for home multimedia appliances did not materialize, and the CDTV was discontinued in 1993,[21] having sold only 30,000 units.[22] Commodore's next attempt at a CD-based console, the Amiga CD32, was considerably more successful.

digiBlast

The digiBlast portable console was launched by Nikko at the end of 2005 and promised to be a cheap alternative (selling at approximately $117.86) to the Nintendo DS and PlayStation Portable. Cartridges for games, cartoon (Winx Club, SpongeBob SquarePants) episodes, and music videos were released on the handheld. A cartridge for MP3 playback and a cartridge with a 1.3-megapixel camera were released as add-ons.[23] However, there was a shortage of chips around the release date and thereafter resulted in a failed launch and loss of consumer interest.[24][25]

Dreamcast

The Dreamcast, released globally in 1999, was Sega's final console before the company focused entirely on software. Although management in the company improved significantly after harsh lessons were learned from the Sega Saturn fiasco, it did little to improve sales of the console. The console also faced stiff competition from the technically superior PlayStation 2 despite being in the market months ahead. The Dreamcast sold less than the Saturn, coming in at 9.13 million units compared to the Saturn's 9.5 million.[26] The console's development was subject to further stress by an economic recession that struck Japan shortly after the console's release, forcing Sega, among other companies, to cut costs to survive.[27][28][29]

Fairchild Channel F

The Fairchild Channel F is a second generation console released in 1976. When the Atari 2600 was release a year later, the console was completely overshadowed.[30] The Fairchild Channel F ended selling only 250,000 units.

FM Towns and FM Towns Marty

The FM Towns and FM Towns Marty are fourth and fifth generation consoles manufactured by Fujitsu. Throughout their few years in the market, both consoles sold an underwhelming 45,000 units.

Gizmondo

The Gizmondo, a handheld gaming device featuring GPS and a digital camera, was released by Tiger Telematics in the United Kingdom on 19 March 2005. With poor promotion, few games (only fourteen were ever released), short battery life, a small screen, competition from the cheaper and more reputable Nintendo DS, digiBlast and PSP, and controversy surrounding the company, the system was a commercial failure. On 23 January 2006, the UK arm of Tiger Telematics went into administration. Several high-ranking Tiger executives were subsequently arrested for fraud and other illegal activities related to the Gizmondo.[31] It is so far the world's worst selling handheld console in history, and due to its failure in the European and American video game markets, it was not released in Australia or Japan. Tiger Telematics went bankrupt when it was discontinued in February 2006, just 11 months after it was released.

HyperScan

Released in late 2006 by Mattel, the HyperScan was the company's first video game console since the Intellivision. It used radio frequency identification (RFID)[32] along with traditional video game technology. The console used UDF format CD-ROMs. Games retailed for $19.99 and the console itself for $69.99 at launch, but at the end of its very short lifespan, prices of the system were down to $9.99, the games $1.99, and booster packs $0.99. The system was sold in two varieties, a cube, and a 2-player value pack. The cube box version was the version sold in stores. It included the system, controller, an X-Men game disc, and 6 X-Men cards. Two player value packs were sold online (but may have been liquidated in stores) and included an extra controller and 12 additional X-Men cards.[33][34] The system was discontinued in 2007 due to poor console, game, and card pack sales.[35] It is featured as one of the ten worst systems ever by PC World magazine.[36]

Neo Geo CD

Released in Japan and Europe between months in 1994 and a year later in North America, the Neo Geo CD was first unveiled at the 1994 Tokyo Toy Show.[37][38] Three versions of the Neo Geo CD were released: a front-loading version, only distributed in Japan, with 25,000 total units built; a top-loading version, marketed worldwide, as the most common model; the Neo Geo CDZ, an upgraded, faster-loading version, released in Japan only. The front-loading version was the original console design, with the top-loading version developed shortly before the Neo Geo CD launch as a scaled-down, cheaper alternative model.[39] The CDZ was released on December 29, 1995[40][41] as the Japanese market replacement for SNK's previous efforts (the "front loader" and the "top loader"). The Neo Geo CD had met with limited success due to it being plagued with slow loading times that could vary from 30 to 60 seconds between loads, depending on the game. Although SNK's American home entertainment division quickly acknowledged that the system simply was unable to compete with the 3D-able powerhouse systems of the day like Nintendo's 64, Sega's Saturn and Sony's PlayStation, SNK corporate of Japan felt they could continue to maintain profitable sales in the Japanese home market by shortening the previous system's load-times.[42] Their Japanese division had produced an excess number of single speed units and found that modifying these units to double speed was more expensive than they had initially thought, so SNK opted to sell them as they were, postponing production of a double speed model until they had sold off the stock of single speed units.[43] As of March 1997, the Neo Geo CD had sold 570,000 units worldwide.[44] Although this was the last known home console released under SNK's Neo Geo line, the newly reincarnated SNK Playmore relaunched the Neo Geo line with the release of the Neo Geo X in 2012.[45]

Neo Geo Pocket and Pocket Color

The two handheld video game consoles, created by SNK Playmore (formerly SNK Corporation), were released between 1998-99 through markets dominated by Nintendo. The Neo Geo Pocket is considered to be an unsuccessful console, as it was immediately succeeded by the Color, a full color device allowing the system to compete more easily with the dominant Game Boy Color handheld, and which also saw a western release. Though the system enjoyed only a short life, there were some significant games released on the system. After a good sales start in both the U.S. and Japan with 14 launch titles (a record at the time)[46] subsequent low retail support in the U.S.,[47] lack of communication with third-party developers by SNK's American management,[48] the craze about Nintendo's Pokémon franchise,[49] anticipation of the 32-bit Game Boy Advance,[49] as well as strong competition from Bandai's WonderSwan in Japan, led to a sales decline in both regions.[50] Meanwhile, SNK had been in financial trouble for at least a year – the company soon collapsed, and was purchased by American pachinko manufacturer Aruze in January 2000.[50][51] Eventually on June 13, 2000, Aruze decided to quit the North American and European markets, marking the end of SNK's worldwide operations and the discontinuation of Neo Geo hardware and software there.[50] The Neo Geo Pocket Color (and other SNK/Neo Geo products) did however, last until 2001 in Japan. It was SNK's last video game console, as the company went bust on October 22, 2001.[50][52] Despite these failures, the Neo Geo Pocket and Pocket Color had been regarded as influential systems.[53][54][49] It also featured an arcade-style microswitched 'clicky stick' joystick, which was praised for its accuracy and being well-suited for fighting games.[55] The Pocket Color system's display and 40-hour battery life were also well received.[49] Although these were the last known systems released under SNK's Neo Geo line, the newly reincarnated SNK Playmore relaunched the Neo Geo line with the release of the Neo Geo X in 2012.[45]

Nintendo 64DD

A disk drive add-on and Internet appliance for the Nintendo 64, it was first announced at 1995's Nintendo Shoshinkai game show event (now called Nintendo World); however, the 64DD was delayed until its release in Japan on December 1, 1999. Nintendo, anticipating poor sales, sold the 64DD through its Randnet subscription service rather than directly to retailers or consumers. As a result, the 64DD was only supported by Nintendo for a short period of time and only nine games were released for it. Most 64DD games were either canceled entirely, released as normal Nintendo 64 cartridges, or ported to other systems such as Nintendo's next-generation GameCube. During its lifetime, of a total of 100k sets, 15,000 sets were sold worldwide, while 85,000 sets became scrap.[56]

N-Gage

Made by the Finnish mobile phone manufacturer Nokia, and released in 2003, the N-Gage is a small handheld console, designed to combine a feature-packed mobile/cellular phone with a handheld games console. The system was mocked for its taco-like design, and sales were so poor that the system's price dropped by $100 within a week after its release. Common complaints included the difficulty of swapping games and the fact that its cellphone feature required users to hold the device "sideways" (i.e. the long edge of the system) against their cheek.[57] A redesigned version, the N-Gage QD, was released to eliminate these complaints. However, the N-Gage brand still suffered from a poor reputation and the QD did not address the popular complaint that the control layout was "too cluttered." The N-Gage failed to reach the popularity of the Game Boy Advance, Nintendo DS, or the Sony PSP. In November 2005, Nokia announced the failure of its product, in light of poor sales (fewer than three million units sold during the platform's three-year run, against projections of six million), and while gaming software is still being produced for its Series 60 phones, Nokia ceased to consider gaming a corporate priority until 2007, when it expected improved screen sizes and quality to increase demand.[58] However, Nokia's presence in the cell phone market was soon eclipsed by the iPhone and later Android phones, causing development to gravitate to them and sealing the fate of the N-Gage brand. In 2012, Nokia abandoned development on the Symbian OS which was the base for N-Gage and transitioned to the Windows Phone.

Nuon

The Nuon, a hybrid of a video game console and DVD player failed due to one of its games such as Iron Soldier 3 being recalled due to incapable controls and a short library of games.

Ouya

The Ouya is an Android based microconsole released in 2013. Even though the OUYA was an outstanding success on Kickstarter, the product was plagued by problems from the beginning. [59] The console was very slow to ship and suffered hardware issues.[60] On top of this, the console had a very limited library of games. [61] The critical reception ranged from lukewarm to outright calling the console a 'scam'. Just two years after its release, the OUYA was in a dire financial situation and negotiated a buyout with Razer. [62]

PC-FX

The PC-FX is the Japan-exclusive successor to the PC Engine, released by NEC in late 1994. Originally intended to compete with the Super Famicom and the Mega Drive, it instead wound up competing with the PlayStation, Sega Saturn, and Nintendo 64. The console's 32-bit architecture was created in 1992, and by 1994 it was outdated, largely due to the fact that it was unable to create 3D images, instead utilizing an architecture that relied on JPEG video. The PC-FX was severely underpowered compared to other fifth generation consoles and had a very low budget marketing campaign, with the system never managing to gain a foothold against its competition or a significant part of the marketshare. The PC-FX was discontinued in early 1998 so that NEC could focus on providing graphics processing units for the upcoming Sega Dreamcast. Around this time, NEC announced that they had only sold 100,000 units with a library of only 62 titles, most of which were dating sims.

Philips CD-i

In 1991, electronics company Philips entered the console gaming business by creating the Compact Disc Interactive console, better known as the CD-i. Like the 3DO, the CD-i was marketed as not only a video game console, but also a multimedia console. Besides CD-i discs, the console was capable of playing Video CDs. The launch price was $700.[63] It was originally intended to be an add-on for the Super NES, but the deal fell through. Nintendo, however, did give Philips the rights and permission to use five Nintendo characters for the CD-i games. In 1993, Philips released two Zelda games, Link: The Faces of Evil and Zelda: The Wand of Gamelon. A year later, Philips released another Zelda game, Zelda's Adventure, and a few months later, a Mario game titled Hotel Mario. All four of these Nintendo-themed games are commonly cited by critics as being among the worst ever made. Much criticism was also aimed at the CD-i's controller.[64] Although it was extensively marketed by Philips, consumer interest remained low. Sales began to slow by 1994, and in 1998, Philips announced that the product had been discontinued. In all, roughly 570,000 units were sold,[65] with 133 games released.

Pioneer LaserActive

Made by the Pioneer LaserDisc Corporation in 1993 (a clone was produced by NEC as well), the LaserActive employed the trademark LaserDiscs as a medium for presenting games and also played the original LaserDisc movies. The LD-ROMs, as they were called, could hold 540 MB of data and up to 60 minutes of analog audio and video. In addition, expansion modules could be bought which allowed the LaserActive to play Genesis and/or TurboGrafx-16 games, among other things. Very poor marketing combined with a high price tag for both the console itself ($969 in 1993) and the various modules (e.g., $599 for the Genesis module compared to $89 for the base console and $229 for Sega CD add-on to play CD-ROM based games) caused it to be quickly ignored by both the gaming public and the gaming press.[66] Less than 40 games were produced in all (at about $120 each),[67] almost all of which required the purchase of one of the modules, and games built for one module could not be used with another. The LaserActive was quietly discontinued one year later after total sales of roughly 10,000 units.

PSX (DVR)

Built upon the PlayStation 2, the PSX enhanced multimedia derivative was touted to bring convergence to the living room in 2003 by including non-gaming features such as a DVD recorder, TV tuner, and multi-use hard drive.[68] The device was considered a failure upon its Japanese release due to its high price and lack of consumer interest,[69] which resulted in the cancellation of plans to release it in the rest of the world. Not only was it an unsuccessful attempt by Sony Computer Entertainment head Ken Kutaragi to revive the ailing consumer electronics division,[70] it also hurt Sony's media convergence plans.[71]

32X

Unveiled at June 1994's Consumer Electronics Show, Sega presented the 32X as the "poor man's entry into 'next generation' games."[72] The product was originally conceived as an entirely new console by Sega Enterprises and positioned as an inexpensive alternative for gamers into the 32-bit era, but at the suggestion of Sega of America research and development head Joe Miller, the console was converted into an add-on to the existing Mega Drive/Genesis and made more powerful, with two 32-bit central processing unit chips and a 3D graphics processor.[72] Despite these changes, the console failed to attract either developers or consumers as the Sega Saturn had already been announced for release the next year.[72] In part because of this, and also to rush the 32X to market before the holiday season in 1994, the 32X suffered from a poor library of titles, including Mega Drive/Genesis ports with improvements to the number of colors that appeared on screen.[73] Originally released at US$159, Sega dropped the price to $99 in only a few months and ultimately cleared the remaining inventory at $19.95.[72] About 665,000 units were sold.[74]

Genesis Nomad

The Nomad, a handheld game console by Sega released in North America in October 1995, is a portable variation of Sega's home console, the Genesis (known as the Mega Drive outside of North America). Designed from the Mega Jet, a portable version of the home console designed for use on airline flights in Japan, Nomad served to succeed the Game Gear and was the last handheld console released by Sega. Released late in the Genesis era, the Nomad had a short lifespan. Sold exclusively in North America, the Nomad was never officially released worldwide, and employs regional lockout. The handheld itself was incompatible with several Genesis peripherals, including the Power Base Converter, the Sega CD, and the Sega 32X. The release was five years into the market span of the Genesis, with an existing library of more than 500 Genesis games.[75] With the Nomad's late release several months after the launch of the Saturn, this handheld is said to have suffered from its poorly timed launch. Sega decided to stop focusing on the Genesis in 1999, several months before the release of the Dreamcast, by which time the Nomad was being sold at less than a third of its original price.[76] Reception for the Nomad is mixed between its uniqueness and its poor timing into the market. Blake Snow of GamePro listed the Nomad as fifth on his list of the "10 Worst-Selling Handhelds of All Time," criticizing its poor timing into the market, inadequate advertising, and poor battery life.[77]

Sega CD

The Sega CD, an add-on for the Sega Genesis set to compete against NEC's Turbo-CD and SNK's Neo Geo CD, but it failed due to numerous reasons.

Sega Saturn

The Sega Saturn was the successor to the Genesis as a 32-bit fifth-generation console, released in Japan in November 1994 and in Western markets mid-1995. The console was designed as a competitor to Sony's PlayStation, released nearly at the same time. With the system selling well in Japan and Sega wanting to get a head start over the PlayStation in North America, the company decided to release the system in May instead of September 1995, which was the same time the PlayStation was going to be released in North America. This left little time to promote the product and limited quantities of the system available at retail. Sega's release strategy also backfired when, shortly after Sega's announcement, Sony announced the price of the PlayStation as being $100 less than the list price for the Saturn.[78][79] The console also suffered from behind the scenes management conflicts and a lack of coordination between the Japanese and North American branches of the company, leading to the Saturn to be released shortly after the release of the 32X, which created distribution and retail problems.[78] By the end of 1996, the PlayStation had sold 2.9 million units in the U.S., more than twice the 1.2 million units sold by the Saturn.[80] With the added competition from the subsequent release of the Nintendo 64, the Saturn lost market share in North America and was discontinued by 1999. With lifetime sales estimated at 9.5 million units worldwide, the Saturn is considered a commercial failure.[81] The failure of Sega's development teams to release a game in the Sonic the Hedgehog series, known in development as Sonic X-treme, has been considered a factor in the console's poor performance. The impact of the failure of the Saturn carried over into Sega's next console, the Dreamcast. However, the console gained interest in Japan and was not officially discontinued until January 4, 2001.

uDraw GameTablet

The uDraw GameTablet is a graphics tablet developed by THQ for use on seventh generation gaming consoles, which was initially released for the Wii in late 2010. Versions for the PlayStation 3 and Xbox 360 were released in late 2011. THQ also invested in several games that would uniquely use the tablet, such as uDraw Pictionary. The Wii version had positive sales, with more than 1.7 million units sold, prompting the introduction of the unit for the other console systems.[82] These units did not share the same popularity; 2011 holiday sales in North America fell $100 million below company targets with more than 1.4 million units left unsold by February 2012.[83] THQ commented that if they had not attempted to sell these versions of uDraw, the company would have been profitable that respective quarter, but instead suffered an overall $56 million loss.[83] Because of this failure, THQ was forced to shelve some of its less-successful franchises, such as the Red Faction series.[84][85] THQ would eventually file for bankruptcy and sell off its assets in early 2013.[86]

Vectrex

This is perhaps the most critically acclaimed "failure" console. Though its independent monitor could display only monochrome visuals, the console's vector-based graphics and arcade-style controller with analog joystick allowed developers to create a strong games library with faithful conversions of arcade hits and critically praised exclusives.[87] However, its release shortly before the North American video game crash of 1983 doomed it to an early grave.[87]

Virtual Boy

This red monochromatic 3-D "virtual reality" system failed due to issues related to players getting eye strain, stiff necks, and headaches when trying to play it, along with the console's price and unportability. It came out in 1995 and was Nintendo's first and thus far only failed console release. Gunpei Yokoi, the designer of the platform and the person largely credited for the success of the original Game Boy handheld and the Metroid series of games, resigned from the company shortly after the Virtual Boy ceased sales in order to start his own company, although for reasons unrelated to the console's success.[88] The Virtual Boy was included in a Time "50 Worst Inventions" list published in May 2010.[89]

Video and computer game software failures

The following is an incomplete list of software that have been deemed commercial failures by industry sources.

APB: All Points Bulletin

APB: All Points Bulletin was a multiplayer online game developed by Realtime Worlds in 2010. The game, incorporating concepts from their previous title Crackdown and past work by its lead developer David Jones, who had helped create the Grand Theft Auto series, was set around the idea of a large-scale urban battle between Enforcers and Criminals; players would be able to partake in large-scale on-going missions between the two sides. The game was originally set as both a Microsoft Windows and Xbox 360 title and as Realtime Worlds' flagship title for release in 2008, but instead the company set about developing Crackdown first, and later focused APB as a Windows-only title, potentially porting the game to the Xbox 360 later. Upon launch in June 2010, the game received lukewarm reviews, hampered by the existence of a week-long review embargo, and did not attract the expected number of subscribers to maintain its business model.[90] Realtime Worlds, suffering from the commercial failure of the game, sold off a second project, Project MyWorld, and subsequently reduced its operations to administration and a skeleton crew to manage the APB servers while they attempted to find a buyer, including possibly Epic Games who had expressed interest in the title. However, without any acceptable offers, the company was forced to shut down APB in September 2010.[91] Eventually, the game was sold to K2 Network, a company that has brought other Asian massive-multiplayer online games to the Western markets as free-to-play titles, and similar changes occurred to APB when it was relaunched by K2.[92]

Battlecruiser 3000AD

One of the most notorious PC gaming failures, Battlecruiser 3000AD (shortened BC3K) was hyped for almost a decade before its disastrous release in the U.S. and Europe. The game was the brainchild of Derek Smart, an independent game developer renowned for lengthy and aggressive online responses to perceived criticism. The concept behind BC3K was ambitious, giving the player the command of a large starship with all the requisite duties, including navigation, combat, resource management, and commanding crew members. Advertisements appeared in the gaming press in the mid-1990s hyping the game as, "The Last Thing You'll Ever Desire."[93] Computer bulletin boards and Usenet groups were abuzz with discussion about the game. As time wore on and numerous delays were announced, excitement turned to frustration in the online community. Smart exacerbated the negative air by posting liberally on Usenet.[93] The posts ignited one of the largest flame wars in Usenet history.[94] During the development cycle, Smart refused to let other programmers have full access to his code and continued to change directions as new technology became available, causing the game to be in development for over seven years.

In November 1996, Take-Two Interactive finally released the game, reportedly over protests from Smart.[93] The game was buggy, even unfinished in many areas, with outdated graphics, MIDI music, a cryptic interface, and almost no documentation, a huge problem since the commands were unintuitive (e.g. Alt-Ctrl-E to fire weapons). It was joked that the only thing that worked properly was the introductory movie. Critics and the gaming community were merciless, panning BC3K across the board. Smart continued to publicly battle his detractors, but kept working on the game, even in the face of harsh criticism. Eventually, a stable, playable version of the game was released as Battlecruiser 3000AD v2.0. Smart eventually released BC3K as freeware and went on to create several sequels under the Battlecruiser and Universal Combat titles.

Beyond Good & Evil

Although critically acclaimed and planned as the first part of a trilogy, Beyond Good & Evil (released in 2003) flopped commercially. Former Ubisoft employee Owen Hughes stated that it was felt that the simultaneous releases of internationally competing titles Tom Clancy's Splinter Cell and Prince of Persia: The Sands of Time and in Europe, XIII (all three published by Ubisoft and all of which had strong brand identity in their markets), made an impact on Beyond Good & Evil's ability to achieve interest with the public. The game's commercial failure led Ubisoft to postpone plans for any subsequent titles in the series.[95][96] A sequel was announced at the end of the Ubidays 2008 opening conference,[97] and an HD version of the original was released for the Xbox 360 and PlayStation 3 via download in 2011. Alain Corre, Ubisoft's Executive Director of EMEA Territories, commented that the Xbox 360 release "did extremely well", but considered this success "too late" to make a difference in the game's poor sales.[98]

Brütal Legend

Brütal Legend is Double Fine Productions' second major title. The game is set in a world based on heavy metal music, includes a hundred-song soundtrack across numerous metal subgenres, and incorporates a celebrity voice cast including Jack Black, Lemmy Kilmister, Rob Halford, Ozzy Osbourne, Lita Ford, and Tim Curry. The game was originally to be published by Vivendi Games via Sierra Entertainment prior to its merger with Activision. Following the merger, Activision declined to publish Brütal Legend, and Double Fine turned to Electronic Arts as their publishing partner, delaying the game's release. Activision and Double Fine counter-sued each other for breach of contract, ultimately settling out of court. The game was designed as an action adventure/real-time strategy game similar to Herzog Zwei; as games in the real-time strategy genre generally do not perform well on consoles, Double Fine was told by both Vivendi and Electronic Arts to avoid stating this fact and emphasize other elements of the game.[99] The game got panned for its real-time strategy elements that were not mentioned within the pre-release marketing, making it a difficult game to sell to players.[100] Furthermore, its late-year release in October 2009 buried the title among many top-tier games, including Uncharted 2, Batman: Arkham Asylum and Call of Duty: Modern Warfare 2. It only sold about 215,000 units within the first month, making it a "retail failure", and though Double Fine had begun on a sequel, Electronic Arts cancelled further development.[101] According to Tim Schafer, president and lead developer of Double Fine, 1.4 million copies of the game had been sold by February 2011.[102] Double Fine would go on to release four smaller and successful titles—Costume Quest, Stacking, Sesame Street: Once Upon a Monster, and Iron Brigade—that were originally envisioned while Brütal Legend was between publishers,[103] and would go on to become an independent development and publishing studio.

Daikatana

One of the more infamous failures in modern PC gaming was Daikatana, which was drastically hyped due to creator John Romero's popular status as one of the key designers behind Doom. However, after being wrought with massive over-spending and serious delays, the game finally launched to incredibly poor critical reaction because of bugs, lackluster enemies, poor gameplay, and terrible production values, all of which were made worse by its heavy marketing campaign proclaiming it as the next "big thing" in first person shooters.[104][105][106]

Dominion: Storm Over Gift 3

The first title released by Ion Storm, Dominion was a real time strategy title similar to Command & Conquer and Warcraft, based as a spin-off to the G-Nome canon. The game was originally developed by 7th Level, but was purchased by Ion Storm for US$1.8 million. The project originally had a budget of US$50,000 and was scheduled to be finished in three months with two staff members. Due to mismanagement and Ion Storm's inexperience, the project took over a year, costing hundreds of thousands of dollars.[107] Dominion was released in July 1998. It received bad reviews and sold poorly, falling far short of recouping its purchase price, let alone the cost of finishing it. The game divided employees working on Ion's marquee title, Daikatana, arguably leading to the walkout of several key development team members. It put a strain on Ion Storm's finances, leading the once well-funded startup to scramble for cash as Daikatana's development extended over several years.[108]

Duke Nukem Forever

Duke Nukem Forever was an entry in the successful Duke Nukem series, initially announced in 1997, but spent fifteen years in development, and was frequently listed as a piece of vaporware video game software. The initial development with the Quake II Engine began in 1996, and the final game was developed by Gearbox Software and released in 2011. The game was not well received and was named by several sites as their "most disappointing" game for the year. Because of its tangled development process, it is very hard to know which companies made and which lost money over the game. According to Gearbox head Randy Pitchford, the game cost 3D Realms head George Broussard US$20-30 million of his own money.[109] The sales were poorer than expected, causing Take-Two to reduce their profit estimate for the quarter,[110] though later in 2011 stated that Duke Nukem Forever would prove to be profitable for the company.[111]

E.T. the Extra-Terrestrial

.jpg)

Based on Steven Spielberg's popular 1982 movie of the same name and reportedly coded in just five weeks,[112] this Atari 2600 game was rushed to the market for the 1982 holiday season.[112]

Despite selling 1.5 million copies,[113] the sales figures came nowhere near Atari's expectations; it had ordered production of five million copies,[112] and many of the sold games were returned to Atari for refunds by consumers who were dissatisfied with the game.[112] It had become an urban legend that Atari had dumped the unsold cartridges of E.T. and other games in a landfill in Alamogordo, New Mexico; however this was confirmed in 2014 when the site was allowed to be excavated, with former Atari personnel affirming they had dumped about 800,000 cartridges total including E.T. and other poorly-selling (and best-selling) games. The financial figures and business tactics surrounding this product are emblematic of the video game crash of 1983 and contributed to Atari's bankruptcy. Atari paid $25 million for the license to produce the game, which further contributed to a debt of $536 million (equivalent to $1.32 billion today). The company was divided and sold in 1984.[112]

Grim Fandango

Known for being the first adventure game by LucasArts to use three-dimensional graphics, Grim Fandango received positive reviews and won numerous awards. It was originally thought that the game sold well during the 1998 holiday season.[114] However, the game's sales appeared to be crowded out by other titles released during the late 1998 season, including Half-Life, Metal Gear Solid and The Legend of Zelda: Ocarina of Time.[101] Based on data provided by PC Data (now owned by NPD Group), the game sold about 95,000 copies up to 2003 in North America, excluding online sales.[115] Worldwide sales are estimated between 100,000 and 500,000 units. Developer Tim Schafer along with others of the Grim Fandango development team would leave LucasArts after this project to begin a new studio (Double Fine Productions). Grim Fandango's relatively modest sales are often cited as a contributing factor to the decline of the adventure game genre in the late 1990s,[116][117] though the title's reputation as a "flop" is to an extent a case of perception over reality, as Schafer has pointed out that the game turned a profit, with the royalty check he eventually received being proof.[118] His perspective is that the adventure genre did not so much lose its audience as fail to grow it while production costs continued to rise. This made adventure games less attractive an investment for publishers; in contrast, the success of first-person shooters caused the console market to boom. The emergence of new distribution channels that did not rely on the traditional retail model would ultimately re-empower the niche genre. Double Fine has since remastered the game for high definition graphics and re-released it through these channels.[119]

The Last Express

Released in 1997 after five years in development, this $6 million[120] adventure game was the brainchild of Jordan Mechner, the creator of Prince of Persia. The game was noted for taking place in almost complete real-time, using Art Nouveau-style characters that were rotoscoped from a 22-day live-action video shoot,[121] and featuring intelligent writing and levels of character depth that were not often seen in computer games. Despite rave reviews,[122][123] Brøderbund, the game's publisher, did little to promote the game, apart from a brief mention in a press release[124] and enthusiastic statements by Brøderbund executives,[125] in part due to the entire Brøderbund marketing team quitting in the weeks before its release.[126] Released in April, the game was not a success, selling only about 100,000 copies,[127] a million copies short of breaking even.[128]

After the release of the game, Mechner's company Smoking Car Productions quietly folded, and Brøderbund was acquired by The Learning Company,[129] who were only interested in Brøderbund's educational software, effectively putting the game out of print. Mechner was later able to reacquire the rights to the game, and in 2012, worked with DotEmu to release an iOS port of the title, before making it to Android as well.[130]

MadWorld

MadWorld is a beat 'em up title for the Wii developed by Platinum Games and distributed by Sega in March 2009. The game was purposely designed as an extremely violent video game.[131] The game features a distinctive black-and-white graphic style that borrows from both Frank Miller's Sin City and other Japanese and Western comics.[131][132] This monotone coloring is only broken by blood that comes from attacking and killing foes in numerous, gruesome, and over-the-top manners. Though there had been violent games available for the Wii from the day it was launched (e.g. Red Steel), many perceived MadWorld as one of the first mature titles for the system, causing some initial outrage from concerned consumers about the normally family-friendly system.[133] MadWorld was well received by critics, but this did not translate into commercial sales; only 123,000 units of the game sold in the United States during its first six months on the market.[134] Sega considered these sales to be "disappointing".[135][136]

Ōkami

Ōkami was a product of Clover Studios with direction by Hideki Kamiya, previously known for his work on the Resident Evil and Devil May Cry series. The game is favorably compared to a Zelda-type adventure, and is based on the quest of the goddess-wolf Amaterasu using a "celestial brush" to draw in magical effects on screen and to restore the cursed land of ancient Nippon. Released first in 2006 on the PlayStation 2, it later received a port to the Wii system, where the brush controls were reworked for the motion controls of the Wii Remote. The game was well received by critics, with Metacritic aggregate scores of 93% and 90% for the PlayStation 2 and Wii versions, respectively,[137][138] and was considered one of the best titles for 2006; IGN named it their Game of the Year.[139] Despite its strong praise, the game sold fewer than 600,000 units by March 2009.[140] These factors have led for Ōkami to be called the "least commercially successful winner of a game of the year award" in the 2010 version of the Guinness World Records Gamer's Edition.[140] Shortly after its release, Capcom disbanded Clover Studios, though many of its employees went on to form Platinum Games and produce Madworld and the more successful Bayonetta.[141] Strong fan support of the game led to a sequel, Ōkamiden, on the Nintendo DS, and a high-definition remake for the PlayStation 3.

Pac-Man (Atari 2600)

The home version of the highly popular Pac-Man arcade game was eagerly anticipated, but was a commercial disappointment for Atari despite being a best-selling game. The game was rushed to make the 1981 Christmas season. In 1982, Atari created 12 million cartridges, even though there were only 10 million Atari 2600s sold at the time, in hopes of the game boosting system sales. Pac-Man did sell close to seven million cartridges, but consumers and critics alike gave it low ratings. The high number of unsold units (over five million), coupled with the expense of a large marketing campaign, led to large losses for Atari.[142] This game and E.T. are often blamed for sparking the video game crash of 1983. Shortly after the disappointment of Pac-Man, Atari reported a huge quarterly loss, prompting parent company Warner Communications to sell the division off in 1984. Atari never regained a prominent position in the home console market.[143]

Psychonauts

Despite being a critical success for its high level of innovation,[144] including winning GameSpot's 2005 Best Game No One Played award, the game initially sold fewer than 100,000 copies.[145] The game led to troubles at publisher Majesco, including the resignation of its CEO and the plummeting of the company's stock,[146] prompting a class-action lawsuit by the company's stockholders.[147] At the time of its release in 2005, the game was considered the "poster child" for failures in innovative games.[148] Its poor sales have also been blamed on a lack of marketing. However, today the game remains a popular title on various digital download services. The creator of Psychonauts, Tim Schafer, has a cult following due to his unique and eccentric style.[149] Eventually, Double Fine would go on to acquire the full rights to publishing the game, and with funding from Dracogen, created a Mac OS X and Linux port of the game, which was sold as part of a Humble Bundle in 2012 with nearly 600,000 bundles sold; according to Schafer, "We made more on Psychonauts [in 2012] than we ever have before."[150] In August 2015, Steamspy assumes approx. 1,157,000 owners of the game on the digital distributor Steam alone.[151]

Shenmue and Shenmue II

Shenmue on the Dreamcast is more notorious for its overambitious budget than its poor sales figures. At the time of release in 1999, the game had the record for the most expensive production costs (over US$70 million),[152] and its five-year production time. In comparison, the games' total sale was 1.2 million copies.[153] Shenmue, however, was a critical hit, earning an average review score of 89%.[154] The game was supposed to be the initial installment of a trilogy. The second installment was eventually released in 2001, but by this time the Dreamcast was floundering, so the game only saw a release in Japan and Europe. Sega eventually released it for North American players for the Xbox, but the poor performance of both titles combined with restructuring have made Sega reluctant to complete the trilogy for fear of failure to return on the investment.[155] However, a Kickstarter campaign has received record support for a third title, with a release set for December 2017.[156]

Sonic Boom: Rise of Lyric and Sonic Boom: Shattered Crystal

Sonic Boom: Rise of Lyric is a spin-off from the Sonic the Hedgehog series, released in 2014 and developed by Big Red Button Entertainment and IllFonic for Sega and Sonic Team, along with its handheld counterpart Sonic Boom: Shattered Crystal, which was developed by Sanzaru Games. Rise of Lyric for the Wii U is considered one of the worst video games of all time due to many glitches, poor gameplay and weak writing. Both games failed commercially, selling only 490,000 copies as of February 2015, making them the lowest-selling games in the Sonic franchise.[157]

Sunset

Sunset, a first-person exploration game involving a housekeeper working for a dictator of a fictional country, was developed by two-person Belgian studio Tale of Tales, who previously had created several acclaimed arthouse style games and other audio-visual projects such as The Path. They wanted to make Sunset a "game for gamers" while still retaining their arthouse-style approach, and in addition to planning on a commercial release, used Kickstarter to gain funding. Sunset only sold about 4000 copies on its release, including those to Kickstarter backers. Tale of Tales opted to close their studio after sinking the company's finances into the game, and believed that if they did release any new games in the future, they would likely shy away from commercial release.[158]

Uru: Ages Beyond Myst

The fourth game in the popular Myst series, released in 2003. It was developed by Cyan Worlds shortly after Riven was completed. The game took Cyan Worlds more than five years and $12 million to complete[159] and was codenamed DIRT ("D'ni in real time"), then MUDPIE (meaning "Multi-User DIRT, Persistent / Personal Interactive Entertainment / Experience / Exploration / Environment"). Though it had generally positive reception,[160][161] the sales were disappointing.[162] In comparison, the first three Myst games had sold more than 12 million units collectively before Uru's release.[163] Uru's poor sales were also considered a factor in financially burdening Cyan, contributing to the company's near closure in 2005.[164]

Arcade game failures

I, Robot

Released by Atari in 1983, I, Robot was the first video game to use 3-D polygon graphics, and the first that allowed the player to change camera angles.[165] It also had gameplay that rewarded planning and stealth as much as reflexes and trigger speed, and included a sandbox mode called "Doodle City," where players could make artwork using the polygons. Production estimates vary, but all agree that there were no more than 1500 units made.[166]

Jack the Giantkiller

In 1982, the President of Cinematronics arranged a one-time purchase of 5000 printed circuit boards from Japan. The boards were used in the manufacture of several games, but the majority of them were reserved for the new arcade game Jack the Giantkiller, based on the classic fairy tale Jack and the Beanstalk. Between the purchase price of the boards and other expenses, Cinematronics invested almost two million dollars into Jack the Giantkiller. It completely flopped in the arcade and many of the boards went unsold, costing the company a huge amount of money at a time when it was already having financial difficulties.[167]

Radar Scope

Radar Scope was one of the first arcade games released by Nintendo. It was released in Japan first, and a brief run of success there led Nintendo to order 3,000 units for the American market in 1980. American operators were unimpressed, however, and Nintendo of America was stuck with about 2,000 unsold Radar Scope machines sitting in the warehouse.[168]

Facing a potential financial disaster, Nintendo assigned the game's designer, Shigeru Miyamoto, to revamp the game. Instead he designed a brand new game that could be run in the same cabinets and on the same hardware as Radar Scope.[169] That new game was the smash hit Donkey Kong, and Nintendo was able to recoup its investment in 1981 by converting the remaining unsold Radar Scope units to Donkey Kong and selling those.[170]

Sundance

Sundance was an arcade vector game, released in 1979. Producer Cinematronics planned to manufacture about 1000 Sundance units, but sales suffered from a combination of poor gameplay and an abnormally high rate of manufacturing defects. The fallout rate in production was about 50%, the vector monitor (made by an outside vendor) had a defective picture tube that would arc and burn out if the game was left in certain positions during shipping,[171] and according to programmer Tim Skelly, the circuit boards required a lot of cut-and-jumpering between mother and daughter boards that also made for a very fragile setup.[172] The units that survived to reach arcade floors were not a hit with gamers—Skelly himself reportedly felt that the gameplay lacked the "anxiety element" necessary in a good game and asked Cinematronics not to release it, and in an April 1983 interview with Video Games Magazine he referred to Sundance as "a total dog".[173]

See also

- List of best-selling video games

- List of video games notable for negative reception

- List of films considered the worst

- List of video games considered the best

- List of television series considered the worst

References

- ↑ Mapping the Canadian Video and Computer Game Industry Archived March 16, 2016, at the Wayback Machine. from The Canadian Video Game Industry with data from the (PDF)

- ↑ Secrets of the Game Business Archived June 17, 2014, at the Wayback Machine. from Google Book Search

- ↑ Video Game Makers Go Hollywood. Uh-Oh. Archived May 28, 2015, at the Wayback Machine. from The New York Times

- ↑ "3DO - 1993-1996 - Classic Gaming". Classicgaming.gamespy.com. Retrieved 2011-10-21.

- ↑ Slagle, Matt (2006-05-10). "How much is too much for a game console?". Associated Press. Retrieved 2007-04-01.

- ↑ Matsushita to apply M2 tech to video editing Television Digest with Consumer Electronics, March 2, 1998

- ↑ "What Console". Retrieved 2009-03-15.

- ↑ Edwards, Benj (2009-07-14). "The 10 Worst Video Game Systems of All Time – Slide 2. Apple Pippin". PCWorld. Retrieved 2011-07-31.

- ↑ 25 worst Tech Products of All Time Archived September 7, 2012, at the Wayback Machine. PC World, May 26, 2006

- ↑ Staff, New York Times (2007). The New York Times Guide To Essential Knowledge: A Desk Reference for the Curious Mind. New York: Macmillan Publishers. p. 472. ISBN 978-0-312-37659-8.

- ↑ Schrage, Michael (May 22, 1984). "Atari Introduces Game In Attempt for Survival". Washington Post: C3.

The company has stopped producing its 5200 SuperSystem games player, more than 1 million of which were sold.

- ↑ Atari Jaguar History Archived May 13, 2016, at the Wayback Machine., AtariAge.com.

- ↑ Stahl, Ted (October 4, 2005). "History of Computing: Videogames – Modern Age". thocp.net.

- ↑ Bricken, Rob (June 22, 2009). "The 11 Worst Mortal Kombat Rip-Offs". Topless Robot. Village Voice Media. Retrieved September 1, 2016.

- ↑ Jacobs, Steven. "Third Time's a Charm (They Hope)". Wired. United States: Conde Nast. Retrieved June 17, 2014.

- ↑ Lesser, Hartley; Lesser, Patricia; Lesser, Kirk (March 1990). "The Role of Computers". Dragon (155): 95–101.

- ↑ "Raze Magazine" (11). September 1991: 6.

- 1 2 Steven Kent (January 5, 1995). "Virtual Fun – Nintendo Adds A New Dimension To Games". Seattle Times. Retrieved November 7, 2013.

- ↑ Sample Contracts - Agreement and Plan of Reorganization - Atari Corp. and JT Storage Inc. - Competitive Intelligence for Investors Archived December 9, 2006, at the Wayback Machine.

- ↑ "Bo Zimmerman's Commodore Gallery". Archived from the original on 2007-12-20.

- ↑ "CDTV.org: History". Web.archive.org. 2009-04-12. Archived from the original on 2009-04-12. Retrieved 2011-10-21.

- ↑ Miller, Skyler (2010-10-03). "CDTV". Allgame. Retrieved 2011-10-21.

- ↑ "Archived copy". Archived from the original on 2016-08-28. Retrieved 2016-02-04.

- ↑ digiBLAST Has Landed Archived April 13, 2016, at the Wayback Machine. - Gizmodo

- ↑ digiBLAST at GreyInnovation

- ↑ Zackariasson, Peter; Wilson, Timothy L.; Ernkvist, Mirko (2012). "Console Hardware: The Development of Nintendo Wii". The Video Game Industry: Formation, Present State, and Future. Routledge. p. 158. ISBN 978-1138803831.

- ↑ Higgens, Tom (September 10, 2009). "Dreamcast: What Sega did next". The Telegraph. Retrieved September 27, 2015.

- ↑ Clark, Noelene; Lu, William (June 9, 2014). "Xbox One vs. PlayStation 4: Charting the video game console evolution". Los Angeles Times. Retrieved October 5, 2015.

Although the Dreamcast was Sega’s last console and a commercial failure, it left a major mark on the industry. The Dreamcast was the first console with a built-in modem for online play — technology used in “Phantasy Star Online,” the first console massively multiplayer online role-playing game. The Dreamcast lost to the PlayStation 2, which could play DVDs. The console was discontinued in 2001, and Sega refashioned itself as a third-party game company.

- ↑ McFarren, Damien (February 22, 2012). "The Rise and Fall of Sega Enterprises". Eurogamer. Retrieved October 5, 2015.

- ↑ Jeff Dunn (July 15, 2013). "Chasing Phantoms - The history of failed consoles". Games Radar. p. 2. Retrieved 2016-11-21.

- ↑ "Gizmondo Bizzaro!". Archived from the original on 2006-03-23. gamerevolution.com

- ↑ "HyperScan – RFID Game System from Mattel". About.com. Retrieved January 10, 2015.

- ↑ "Mattel and Fisher-Price Customer Service". Service.mattel.com. Retrieved 2013-05-13.

- ↑ "Mattel Makes Contactless RFID Connection with Innovision R&T for Innovative HyperScan™ Games Platform". Innovision-Group. October 18, 2006. Archived from the original on October 10, 2007. Retrieved January 10, 2015. - Site archived by Wayback Machine

- ↑ "Mattel Consumer Relations Answer Center – Product Detail >> Radica >> Radica Electronic Games". Service.mattel.com. Retrieved 2011-07-31.

- ↑ Edwards, Benj (2009-07-14). "The 10 Worst Video Game Systems of All Time – Slide 5:7. Mattel Hyperscan". PCWorld. Retrieved 2011-07-31.

- ↑ "Neo Geo CD Brings Arcade Home". Electronic Gaming Monthly. Ziff Davis (61): 60. August 1994.

- ↑ "The Neo Geo CD: An Arcade in Your Home". GamePro. IDG (79): 16. April 1995.

- ↑ "SNK CD for Spring". Electronic Gaming Monthly. Ziff Davis (63): 62. October 1994.

- ↑ Neo Geo CD World at the Wayback Machine (archived December 17, 2010) (French)

- ↑ http://www.obsolete-tears.com/snk-neogeo-cd-machine-226.html (French)

- ↑ "Archived copy". Archived from the original on 2016-03-04. Retrieved 2015-12-11.

- ↑ "Neo CD to Be Single Speed". Electronic Gaming Monthly. Ziff Davis (79): 20. February 1996.

- ↑ Consoles +, issue 73 Archived April 23, 2016, at the Wayback Machine.

- 1 2 "NEOGEO X – Witness the rebirth of the Neo Geo". SNK Playmore. Retrieved 2015-12-10.

- ↑ "Neo Geo Pocket Color". Archived from the original on February 29, 2000.

- ↑ "The end of an era: a cruel look at what we missed: Part 2". June 2000.

- ↑ "NeoGeo Pocket Color Feature". Retrieved October 9, 2010.

- 1 2 3 4 "Neo Geo Pocket Color 101, A beginner's guide".

- 1 2 3 4 "The History of SNK".

- ↑ "Archived copy". Archived from the original on 2016-03-20. Retrieved 2015-02-09. History for SNK Corporation

- ↑ "A Sign Of The Times: Game Over For SNK". IGN UK. November 2, 2001.

- ↑ "Neo Geo Pocket Color: The Portable That Changed Everything".

- ↑ "Archived copy". Archived from the original on 2016-08-29. Retrieved 2016-08-02. The life and times of the Neo Geo Pocket Color

- ↑ "Hardware Classics: SNK Neo Geo Pocket Color".

- ↑ "NUS: Nintendo64". Maru-chang.com. Retrieved 2011-10-21.

- ↑ Nokia's Folly Archived November 6, 2016, at the Wayback Machine. CNN Money, October 6, 2003

- ↑ Nokia holds fire on mobile gaming vuunet.com, Nov 23, 2005

- ↑ "Archived copy". Archived from the original on 2016-11-20. Retrieved 2016-06-30.

- ↑ "Archived copy". Archived from the original on 2016-09-09. Retrieved 2016-06-30.

- ↑ "Archived copy". Archived from the original on 2016-05-12. Retrieved 2016-06-30.

- ↑ "Archived copy". Archived from the original on 2016-05-18. Retrieved 2016-06-30.

- ↑ "COMPANY NEWS; New Philips CD". The New York Times. 1992-04-02. Retrieved 2010-01-03.

- ↑ "Top 10 Tuesday: Worst Game Controllers". IGN. 2006-02-21. Retrieved 2009-08-07.

- ↑ Blake Snow (2007-05-04). "The 10 Worst-Selling Consoles of All Time". GamePro.com. Archived from the original on 2008-09-05. Retrieved 2007-11-25.

- ↑ "Archived copy". Archived from the original on 2012-10-19. Retrieved 2013-07-02. allgame

- ↑ Pink Godzilla - Pioneer LaserActive>

- ↑ "Sony adds Bells and Whistles to PlayStation 2" Archived May 25, 2011, at the Wayback Machine., San Francisco Gate, May 29, 2003

- ↑ "Next Gen Console Wars: Revenge of Kutaragi" Archived January 23, 2013, at the Wayback Machine., TeamXbox website, June 13, 2005

- ↑ "Mr. Idei's Kurosawa Ending" Archived March 4, 2016, at the Wayback Machine., Robert X. Cringely, March 10, 2005

- ↑ "PSX Failure is a Blow to Sony's Convergence Dreams". Archived from the original on 2007-12-13. Rob Fahey, October 9, 2004

- 1 2 3 4 Kent, Steven L. (2001). "The "Next" Generation (Part 1)". The Ultimate History of Video Games: The Story Behind the Craze that Touched our Lives and Changed the World. Roseville, California: Prima Publishing. ISBN 0-7615-3643-4.

- ↑ Buchanan, Levi (2008-10-24). "32X Follies". IGN. Retrieved 2013-08-13.

- ↑ "Videospiel-Algebra". Man!ac Magazine. May 1995.

- ↑ Kent, Steven L. (2001). The Ultimate History of Video Games: The Story Behind the Craze that Touched our Lives and Changed the World. Roseville, California: Prima Publishing. pp. 508, 531. ISBN 0-7615-3643-4.

- ↑ Retro Gamer staff. "Retroinspection: Sega Nomad". Retro Gamer. Imagine Publishing (69): 46–53.

- ↑ Snow, Blake (2007-05-04). "The 10 Worst-Selling Consoles of All Time". GamePro. Archived from the original on 2008-09-05. Retrieved 2007-10-28.

- 1 2 Parish, Jeremy (November 18, 2014). "The Lost Child of a House Divided: A Sega Saturn Retrospective". US Gamer. Retrieved September 9, 2015.

- ↑ Gallagher, Scott; Park, Seung Ho (February 2002). "Innovation and Competition in Standard-Based Industries: A Historical Analysis of the U.S. Home Video Game Market". IEEE Transactions on Engineering Management. 49 (1): 67–82.

- ↑ Schilling, Mellissa A. (Spring 2003). "Technological Leapfrogging: Lessons From the U.S. Video Game Console Industry". California Management Review. 45 (3): 12, 23.

Lack of distribution may have contributed significantly to the failure of the Sega Saturn to gain an installed base. Sega had limited distribution for its Saturn launch, which may have slowed the building of its installed base both directly (because consumers had limited access to the product) and indirectly (because distributors that were initially denied product may have been reluctant to promote the product after the limitations were lifted). Nintendo, by contrast, had unlimited distribution for its Nintendo 64 launch, and Sony not only had unlimited distribution, but had extensive experience with negotiating with retailing giants such as Wal-Mart for its consumer electronics products.

- ↑ Lefton, Terry (1998). "Looking for a Sonic Boom". Brandweek. 9 (39): 26–29.

- ↑ Dutton, Fred (2011-05-03). "THQ announces uDraw for PS3/360". Eurogamer. Retrieved 2012-04-10.

- 1 2 Dutton, Fred (2012-02-02). "THQ details full extent of uDraw disaster". Eurogamer. Retrieved 2012-04-10.

- ↑ Sherr, Ian (2012-02-02). "UPDATE: THQ Attempts To Remake Business After UDraw Failure". Dow Jones Newswires. Retrieved 2012-04-10.

- ↑ Priest, Simon (2013-03-22). "THQ's UDraw failure "invalidated" Saints Row: The Third's success". Strategy Informer. Retrieved 2013-06-25.

- ↑ Kohler, Chris (2013-01-23). "THQ Is Dead. Here's Where Its Games Are Going". Wired. Retrieved 2013-06-25.

- 1 2 Barton, Matt and Loguidice, Bill. (2007). A History of Gaming Platforms: The Vectrex Archived April 16, 2016, at the Wayback Machine., Gamasutra.

- ↑ "n-sider profile, Gunpei Yokoi". Archived from the original on 2004-04-04.

- ↑ Fletcher, Dan (2010-05-27). "The 50 Worst Inventions – Nintendo Virtual Boy". Time. Retrieved 2010-05-29.

- ↑ Elliot, Phil (2010-08-17). "Realtime Worlds enters administration". Gamesindustry.biz. Retrieved 2010-10-10.

- ↑ Minkley, Johnny (2010-09-16). "APB "plug to be pulled" within 24 hours". Eurogamer. Retrieved 2010-10-10.

- ↑ Watts, Steve (2010-11-11). "APB Bought by Free-to-Play Company K2 Network". 1UP.com. Retrieved 2010-11-29.

- 1 2 3 "The 25 Dumbest Moments in Gaming". GameSpy. Retrieved 2007-06-04.

- ↑ "Battlecriuser Flamer War Follies". Bill Huffman. Retrieved 2007-06-04.

- ↑ "Jaded Beauty". Jump Button magazine. Retrieved 2007-01-10.

- ↑ "It would be 'good to finish' BG&E – Michel Ancel". EuroGamer. Archived from the original on 2007-09-27. Retrieved 2007-01-10.

- ↑ "Beyond Good & Evil 2 revealed at Ubidays 2008". Joystiq. Retrieved 2007-01-10.

- ↑ Bertz, Matt (2011-12-06). "Ubi Uncensored". 223. pp. 40–49. Retrieved 2012-06-26.

- ↑ Esmurdoc, Caroline (2009-03-25). "Postmortem: Double Fine's Brutal Legend". Gamasutra. Retrieved 2010-05-25.

- ↑ Johnson, Stephan (2009-11-13). "Brutal Legend And DJ Hero Fail To Crack Top Ten In Sales". G4TV. Retrieved 2009-11-19.

- 1 2 Denton, Jake (2011-11-18). "5 great games that got trampled in the Christmas rush". Computer and Video Games. Retrieved 2011-11-18.

- ↑ Nutt, Christian (2011-02-11). "Schafer Admits Fantasy Of Flatulence On Youth". Gamasutra. Retrieved 2011-02-11.

- ↑ Parkin, Simon (2010-07-15). "Develop: Double Fine's Schafer On 'Amnesia Fortnights' And The Pitfalls Of AAA". Gamasutra. Retrieved 2010-07-15.

- ↑ "John Romero's Daikatana for PC". GameRankings. 2000-04-14. Retrieved 2011-10-21.

- ↑ post a comment. "The 10 biggest flops in video games (2/3), page 2, Feature Story from". GamePro. Archived from the original on 2011-06-07. Retrieved 2011-10-21.

- ↑ Morning Edition (2005-08-17). "From 'Doom' to Gloom: The Story of a Video Game Flop". NPR. Retrieved 2011-10-21.

- ↑ The 25 Dumbest Moments in Video Game History Archived June 12, 2012, at the Wayback Machine., GameSpy, June 2003

- ↑ Biederman, Christine (January 14, 1999). "Stormy Weather: Hot new computer game maker ION Storm appears to have all it needs for success -- top talent, plenty of money, and legions of anxious fans. So why is its future so cloudy?". Dallas Observer. Archived from the original on 2004-11-13.

- ↑ "Duke Nukem Forever May Have Cost George Broussard $20-30 Million". Computer and Video Games. 7 October 2010.

- ↑ "Analysts Disappointed in Duke, Far Less Sales Than Expected". Playstation Lifestyle. 6 July 2011.

- ↑ "Duke Nukem profitable, L.A. Noire ships 4 million says Take-Two". PlayStation Universe. 9 August 2011. Retrieved 10 August 2011.

- 1 2 3 4 5 "Five Million E.T. Pieces". Snopes. 2007-02-02. Retrieved 2009-02-12.

- ↑ Matt Matthews (2007-08-13). "The 30 defining moments in gaming". Next-Gen.biz. Archived from the original on 2007-12-16. Retrieved 2008-01-31.

- ↑ Albertson, Joshua (1998-12-08). "Tech Gifts of the Season". Smart Money. Archived from the original on 2004-12-21. Retrieved 2008-08-23.

- ↑ Sluganski, Randy. "(Not) Playing the Game, Part 4". Just Adventure. Archived from the original on 2007-10-22. Retrieved 2007-12-02.

- ↑ Cook, Daniel (2007-05-07). "The Circle of Life: An Analysis of the Game Product Lifecycle". Gamasutra. Retrieved 2008-03-03.

- ↑ Lindsay, Greg (1998-10-08). "Myst And Riven Are A Dead End. The Future Of Computer Gaming Lies In Online, Multiplayer Worlds". Salon. Archived from the original on January 30, 2011. Retrieved 2008-03-13.

- ↑ Martins, Todd (2015-01-24). "Game designer Tim Schafer's 'Grim' path tracks adventure genre's growth". Hero Complex. Retrieved 2015-05-25.

- ↑ Edgar, Sean (2014-02-04). "A New Age For Tim Schafer And Double Fine Productions". Past Magazine. Retrieved 2015-05-25.

- ↑ "The Last Express Interview – Archived from GamesDomain.com". gamesdomain.com. Retrieved 2006-08-19.

- ↑ "Mark Moran – Programming – Resume". Mark Moran. Retrieved 2006-08-19.

- ↑ "The Last Express Review (from the Internet Archive)". Games Domain. Archived from the original on 1997-06-13. Retrieved 2006-08-19.

- ↑ "The Last Express Review". Computer Games Online. Archived from the original on 1997-06-07. Retrieved 2006-08-19.

- ↑ "Broderbund Software – Press News". Coming Soon Magazine. Retrieved 2006-08-19.

- ↑ "Conference Call, 03/27/97: Broderbund Q2". The Motley Fool. Retrieved 2006-08-19.

- ↑ Remo, Chris (2008-11-28). "The Last Express: Revisiting An Unsung Classic". Gamasutra. Retrieved 2009-02-28.

- ↑ "Mark Moran – Programming – Interviews". Mark Moran. Retrieved 2006-08-19.

- ↑ "Mark Moran – Programming – The Last Express". Mark Moran. Retrieved 2006-08-19.

- ↑ "The Learning Co. buys Broderbund". CNET News. Archived from the original on 2004-11-26. Retrieved 2006-08-19.

- ↑ Conduit, Jessica (2012-03-16). "All aboard The Last Express on iOS, Mechner's classic adventure revamped". Joystiq. Retrieved 2013-02-15.

- 1 2 McEachern, Martin (June 2009). "It's a Mad, Mad, Mad, MadWorld". 32 (6). Computer Graphics World.

- ↑ Driftwood (September 20, 2008). "Interview: Atsushi Inaba". Gamersyde.com. Retrieved 2009-04-04.

- ↑ Black, Rosemary (2009-03-12). "Parents groups protest release of Wii's violent video game, 'Madworld'". New York Daily News. Archived from the original on 2009-03-13. Retrieved 2010-03-18.

- ↑ Matthews, Matt (September 14, 2009). "Analysis: Where Now For M-Rated Wii Games?". Gamasutra.com. Retrieved 2009-09-14.

- ↑ John, Tracey (2009-08-12). "Wii Audience a 'Mismatch' for MadWorld, says Sega West President". Wired. Retrieved 2010-03-18.

- ↑ Radd, David (2010-03-18). "Wii Audience a 'Mismatch' for MadWorld, says Sega West President". Industry Gamers. Retrieved 2010-03-18.

- ↑ "Ōkami Reviews". MetaCritic. Retrieved 2007-08-09.

- ↑ "Okami (wii: 2007)". Metacritic. Retrieved 2008-04-12.

- ↑ Roper, Chris. "IGN.com Presents the Best of 2006 - Overall Game of the Year". IGN. Retrieved 2007-08-09.

- 1 2 2010 Guinness World Records Gamers Edition. BradyGames. 2010. ISBN 978-0-7440-1183-8.

- ↑ Ermac (2006-10-12). "Capcom Dissolving Clover Studios". ErrorMacro. Archived from the original on 2007-09-28. Retrieved 2007-08-11.

- ↑ "Five Million E.T. Pieces". Snopes.com. Retrieved 2009-10-09.

- ↑ Mikkelson, Barbara and David (2001-03-21). "Five Million E.T. Pieces". Urban Legends Reference Pages. Retrieved 2006-07-20.

- ↑ "Gamespot: Best of 2005 Special Achievement" Archived October 7, 2013, at the Wayback Machine., GameSpot

- ↑ "Life After Shelf Death". The Escapist. Archived from the original on 2007-11-15., The Escapist, 13 November 2007

- ↑ "Majesco stock plummets as CEO quits", GameSpot Xbox, July 12, 2005

- ↑ "Stockholders sue Majesco en masse", GameSpot Xbox, July 19, 2005

- ↑ "Bitter medicine: What does the game industry have against innovation?" Archived October 4, 2013, at the Wayback Machine., GameSpot Xbox, December 20, 2005

- ↑ Caron, Frank (2007-10-12). "Game Informer details new Tim Schafer title, starring Jack Black". Arstechnica.com. Retrieved 2011-12-05.

- ↑ "Double Fine Double Feature". Polygon. 2012-12-13. Retrieved 2013-02-05.

- ↑ Psychonauts Archived May 6, 2016, at the Wayback Machine. on Steamspy.com (2015-08-13)

- ↑ "Most Expensive Video Game". October 9, 2006. Retrieved 2007-04-14.

- ↑ "Microsoft Announces Leading Sega Games for Xbox". Microsoft. 2001-10-12. Archived from the original on 2009-03-19. Retrieved 2007-12-12.

- ↑ "Shenmue – DC". Archived from the original on 2008-01-18. on GameRankings

- ↑ "SEGA says they'll trade exclusivity for Shenmue funding".

- ↑ "Shenmue III Brings Back Ryo's Japanese, English Voice Actors". Anime News Network. 2015-07-16. Retrieved 2015-07-16.

- ↑ "Sonic Boom games shifted just 490,000 copies?".

- ↑ Blake, Vikki (2015-06-22). "SUNSET DEV TALE OF TALES QUITS COMMERCIAL GAME DEVELOPMENT". IGN. Retrieved 2015-08-03.

- ↑ Gerianos, Nicholas (2003-11-23). "Creator of 'Myst' launches new game". USA Today. Retrieved 2008-09-17.

- ↑ "Uru: Ages Beyond Myst (pc: 2003): Reviews". Metacritic. Retrieved 2008-10-18.

- ↑ "Uru: Ages Beyond Myst Reviews". GameRankings. Retrieved 2008-10-15.

- ↑ Hamilton, Anita (2004-08-09). "Secrets of The New Myst". Time. Retrieved 2008-11-17.

- ↑ "New and Expanded Features Revealed for Highly-Anticipated Uru: Ages Beyond 'Myst'" (Press release). Business Wire. 2003-05-07. Retrieved 2008-09-18.

- ↑ Allin, Jack (2005-09-04). "Sayonara to Cyan Worlds". Adventure Gamers. Retrieved 2008-11-01.

- ↑ "Jeff Anderson's ''I, Robot'' page". Ionpool.net. 2004-02-18. Retrieved 2011-10-21.

- ↑ "''I, Robot entry on KLOV". Arcade-museum.com. Retrieved 2011-10-21.

- ↑ "History of Cinematronics Inc.". Archived from the original on 2008-02-15. Jack and the 'Company' Killer

- ↑ "Experience the invasion of the SONIC GAMMA RAIDERS with supernatural "Laser Sound."". Archived from the original on 2007-12-14. Radar Scope @ Everything2.com

- ↑ "Do the Donkey Kong (1980-1983)". GameSpot. Archived from the original on 2007-10-14. GameSpot: The History of Nintendo

- ↑ "Radar Scope at Arcade-History.com". Archived from the original on 2008-02-12.

- ↑ "Sundance at Arcade-History.com". Archived from the original on 2008-02-12.

- ↑ "Tim Skelly's history of Cinematronics". Dadgum.com. 1999-06-01. Retrieved 2011-10-21.

- ↑ interview with Tim Skelly Archived November 27, 2016, at the Wayback Machine. Video Games magazine

External links

- The Dumbest 25 moments in gaming from GameSpy

- The Silicon Valley 10 & 1 06.16.10: Top 10 Console Failures!