Mesosaurus

| Mesosaurus Temporal range: Cisuralian, 299–280 Ma | |

|---|---|

| |

| Mesosaurus tenuidens | |

| Scientific classification | |

| Kingdom: | Animalia |

| Phylum: | Chordata |

| Class: | Reptilia |

| Clade: | †Parareptilia |

| Order: | †Mesosauria |

| Family: | †Mesosauridae |

| Genus: | †Mesosaurus Gervais, 1864-66 |

| Type species | |

| †Mesosaurus tenuidens Gervais, 1864-66 | |

| Synonyms | |

| |

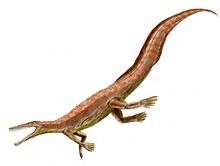

Mesosaurus (meaning "middle lizard") is an extinct genus of reptile from the Early Permian of southern Africa and South America. Along with the genera Brazilosaurus and Stereosternum, it is a member of the family Mesosauridae and the order Mesosauria. Mesosaurus was long thought to have been one of the first marine reptiles, although new data suggests that at least those of Uruguay inhabited a hypersaline water body, rather than a typical marine environment.[1] In any case, it had many adaptations to a fully aquatic lifestyle. It is usually considered to have been anapsid, although Friedrich von Huene considered that it was synapsid,[2] and this hypothesis has been revived recently.[3][4]

Description

Mesosaurus had a long skull that was larger than that of Stereosternum and had longer teeth. The teeth are angled outwards, especially those at the tips of the jaws.[5]

The bones of the postcranial skeleton are thick, having undergone pachyostosis. Mesosaurus is unusual among reptiles in that it possesses a cleithrum. A cleithrum is a type of dermal bone that overlies the scapula, and is usually found in more primitive bony fish and tetrapods. The head of the interclavicle of Mesosaurus is triangular, unlike those of other early reptiles, which are diamond-shaped.[6]

Palaeobiology

Mesosaurus was one of the first reptiles to return to the water after early tetrapods came to land in the Late Devonian or later in the Paleozoic.[7] It was around 1 metre (3.3 ft) in length, with webbed feet, a streamlined body, and a long tail that may have supported a fin. It probably propelled itself through the water with its long hind legs and flexible tail. Its body was also flexible and could easily move sideways, but it had heavily thickened ribs, which would have prevented it from twisting its body.[8]

Mesosaurus had a small skull with long jaws. The nostrils were located at the top, allowing the creature to breathe with only the upper side of its head breaking the surface, in a similar manner to a modern crocodile. The teeth were originally thought to have been straining devices for the filter feeding of planktonic organisms.[8] However, this idea was based on the assumption that the teeth of Mesosaurus were numerous and close together in the jaws. Newly examined remains of Mesosaurus show that it had fewer teeth, and that the dentition was suitable for catching small nektonic prey such as crustaceans.[5]

The pachyostosis seen in the bones of Mesosaurus may have enabled it to reach neutral buoyancy in the upper few meters of the water column. The additional weight may have stabilized the animal at the water's surface. Alternatively, it could have given Mesosaurus greater momentum when gliding underwater. While many features suggest a wholly aquatic lifestyle,[9] Mesosaurus may have been able to move onto land for short periods of time. The elbows and ankles had restricted movement, making walking impossible. It is more likely that if Mesosaurus moved onto land, it would push itself forward in a similar way to living female sea turtles when nesting on beaches.[6]

Fossil embryos of Mesosaurus have been discovered in Uruguay and Brazil. These fossils are the earliest record of amniote embryos, although amniotes are inferred to have had this reproductive strategy since their first appearance in the Late Carboniferous. Prior to their description, the oldest known amniotic embryos were from the Triassic. The embryo fossils of Mesosaurus are not surrounded by egg shells, suggesting that Mesosaurus, like many other marine reptiles, gave live birth. If this interpretation is correct, these embryos represent the earliest known example of vivipary in the fossil record. One Mesosaurus specimen called MCN-PV 2214 clearly preserves a medium-size adult and a small embryo in utero. Other specimens include small individuals, which may be embryonic, in association with the bones of larger individuals that may be their parents.[11]

Distribution

Mesosaurus was significant in providing evidence for the theory of continental drift, because its remains were found in southern Africa and eastern South America, two widely separated regions.[12] As Mesosaurus was a coastal animal, and therefore could not have crossed the Atlantic Ocean, this distribution indicated that the two continents used to be joined together.

References

- ↑ Piñeiro, G.; Ramos, A.; Goso, C.; Scarabino, F.; Laurin, M. (2012). "Unusual environmental conditions preserve a Permian mesosaur-bearing Konservat-Lagerstätte from Uruguay". Acta Palaeontologica Polonica. 57 (2): 299–318. doi:10.4202/app.2010.0113.

- ↑ Huene, F. von (1940). "Osteologie und systematische Stellung von Mesosaurus". Palaeontographica. Abteilung A. Palaeozoologie-Stratigraphie. 92: 45–58.

- ↑ Piñeiro, Graciela (2008). "Los mesosaurios y otros fosiles de fines del Paleozoico". In D. Perera. Fósiles de Uruguay. DIRAC, Montevideo.

- ↑ Piñeiro, G.; Ferigolo, J.; Ramos, A.; Laurin, M. (2012). "Cranial morphology of the Early Permian mesosaurid Mesosaurus tenuidens and the evolution of the lower temporal fenestration reassessed". Comptes Rendus Palevol. 11 (5): 379–391. doi:10.1016/j.crpv.2012.02.001.

- 1 2 Modesto, S.P. (2006). "The cranial skeleton of the Early Permian aquatic reptile Mesosaurus tenuidens: implications for relationships and palaeobiology". Zoological Journal of the Linnean Society. 146 (3): 345–368. doi:10.1111/j.1096-3642.2006.00205.x.

- 1 2 Modesto, S.P. (2010). "The postcranial skeleton of the aquatic parareptile Mesosaurus tenuidens from the Gondwanan Permian". Journal of Vertebrate Paleontology. 30 (5): 1378–1395. doi:10.1080/02724634.2010.501443.

- ↑ Laurin, Michel (2010). How Vertebrates left the Water (illustrated ed.). University of California Press. pp. xv + 199. ISBN 978-0-520-26647-6.

- 1 2 Palmer, D., ed. (1999). The Marshall Illustrated Encyclopedia of Dinosaurs and Prehistoric Animals. London: Marshall Editions. p. 65. ISBN 1-84028-152-9.

- ↑ Canoville, Aurore; Michel Laurin (2010). "Evolution of humeral microanatomy and lifestyle in amniotes, and some comments on paleobiological inferences". Biological Journal of the Linnean Society. 100 (2): 384–406. doi:10.1111/j.1095-8312.2010.01431.x.

- ↑ MacGregor, J.H. (1908) Mesosaurus brasiliensis nov. sp. IN: White, I.C. (1908) Commission for Studies on Brazilian Coal Mines - Final Report; (Bilingual report, Portuguese & English), Imprensa Nacional, Rio de Janeiro, Brazil, 617 p.: Part II, pp. 301-336.

- ↑ Piñeiro, G.; Ferigolo, J.; Meneghel, M.; Laurin, M. (2012). "The oldest known amniotic embryos suggest viviparity in mesosaurs". Historical Biology. in press. doi:10.1080/08912963.2012.662230.

- ↑ Piñeiro, Graciela (2008). D. Perera, ed. Fósiles de Uruguay. DIRAC, Montevideoy.

- Parker, Steve. Dinosaurus: the complete guide to dinosaurs. Firefly Books Inc, 2003. Pg. 90

- Carroll, R. L. (1988). Vertebrate Paleontology and Evolution. W.H. Freeman and Company.

- LeGrand, Homer Eugene (1988). Drifting Continents and Shifting Theories: The Modern Revolution in Geology and Scientific Change (illustrated ed.). Cambridge University Press. p. 313. ISBN 9780521311052. ISBN 0-521-31105-5.

- Margulis, Lynn; Clifford Matthews; Aaron Haselton. Environmental Evolution: Effects of the Origin and Evolution of Life on Planet Earth. Contributor Clifford Matthews, Aaron Haselton (2nd ed.). p. 338. ISBN 9780262631976. ISBN 0-262-63197-0.

- Sepkoski, J. J. (2002). "A compendium of fossil marine animal genera". Bulletins of American Paleontology. 363: 1–560.