Mount Hua

| Mount Hua | |

|---|---|

Mount Hua's West peak. | |

| Highest point | |

| Elevation | 2,154 m (7,067 ft) |

| Coordinates | 34°29′N 110°05′E / 34.483°N 110.083°E |

| Geography | |

| Parent range | Qin Mountains |

| Climbing | |

| Easiest route | Cable Car |

| Mount Hua | |||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

"Mount Hua" in Simplified (top) and Traditional (bottom) Chinese | |||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Traditional Chinese | 華山 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Simplified Chinese | 华山 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||

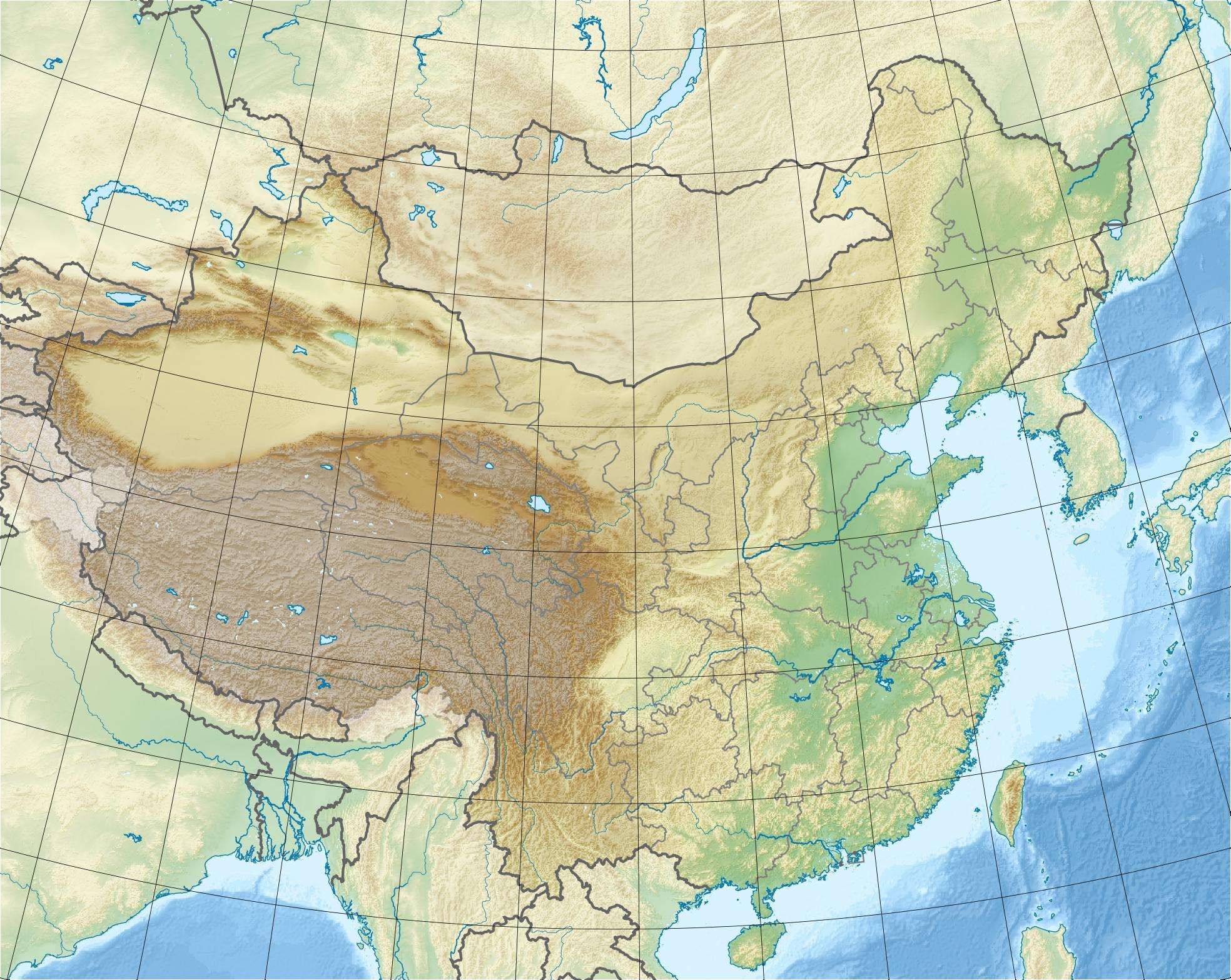

Mount Hua (simplified Chinese: 华山; traditional Chinese: 華山; pinyin: Huà shān[1]) is a mountain located near the city of Huayin in Shaanxi province, about 120 kilometres (75 mi) east of Xi'an. It is the western mountain of the Five Great Mountains of China, and has a long history of religious significance. Originally classified as having three peaks, in modern times the mountain is classified as five main peaks, of which the highest is the South Peak at 2,154.9 metres (7,070 ft).

Geography

Mount Hua is situated in Huayin City, which is 120 kilometres (about 75 miles) from Xi'an. It is located near the southeast corner of the Ordos Loop section of the Yellow River basin, south of the Wei River valley, at the eastern end of the Qin Mountains, in southern Shaanxi province. It is part of the Qinling or Qin Mountains, which divide not only northern and southern Shaanxi, but also China.

Summits

Traditionally, only the giant plateau with its summits to the south of the peak Wuyun Feng (五雲峰, Five Cloud Summit) was called Taihua Shan (太華山, Great Flower Mountain). It could only be accessed through the ridge known as Canglong Ling (蒼龍嶺, Dark Dragon Ridge) until a second trail was built in the 1980s to go around Canglong Ling. Three peaks were identified with respective summits: the East, South, and West peaks.

The East peak consists of four summits. The highest summit is Zhaoyang Feng (朝陽峰, Facing Yang Summit, i.e. the summit facing the sun). Its elevation is reported to be 2,096 m (6,877 ft) and its name is often used as the name for the whole East Peak. To the east of Zhaoyang Feng is Shilou Feng (石樓峰, Stone Tower Summit), to the south is Botai Feng (博臺峰, Broad Terrace Summit) and to the west is Yunű Feng (玉女峰, Jade Maiden Summit). Today, Yunű Feng considered its own peak, most central on the mountain.

The South peak consists of three summits. The highest summit is Luoyan Feng (落雁峰, Landing Goose Summit), with an elevation of 2,154 m (7,067 ft). To the east is Songgui Feng (松檜峰, Pines and Junipers Summit), and to the west is Xiaozi Feng (孝子峰, Filial Son Summit).

The West peak has only one summit and it is known as Lianhua Feng (蓮花峰) or Furong Feng (芙蓉峰), both meaning Lotus Flower Summit. The elevation is 2,082 m (6,831 ft).

With the development of new trail to Hua Shan in the 3rd through 5th century along the Hua Shan Gorge, the peak immediately to the north of Canglong Ling, Yuntai Feng (雲臺峰, Cloud Terrace Peak), was identified as the North peak. It is the lowest of the five peaks with an elevation of 1,614.9 m (5,298 ft).

History

As early as the 2nd century BCE, there was a Daoist temple known as the Shrine of the Western Peak located at its base. Daoists believed that in the mountain lives the god of the underworld. The temple at the foot of the mountain was often used for spirit mediums to contact the god and his underlings. Unlike Taishan, which became a popular place of pilgrimage, Huashan, because of the inaccessibility of its summits, only received Imperial and local pilgrims, and was not well visited by pilgrims from the rest of China.[2] Huashan was also an important place for immortality seekers, as many herbal Chinese medicines are grown and powerful drugs were reputed to be found there. Kou Qianzhi (365–448), the founder of the Northern Celestial Masters received revelations there, as did Chen Tuan (920–989), who spent the last part of his life in hermitage on the west peak. In the 1230s, all the temples on the mountain came under control of the Daoist Quanzhen School.[3] In 1998, the management committee of Huashan agreed to turn over most of the mountain's temples to the China Daoist Association. This was done to help protect the environment, as the presence of taoists and nuns deters poachers and loggers.[4]

Temples

Huashan has a variety of temples and other religious structures on its slopes and peaks. At the foot of the mountains is the Cloister of the Jade Spring (玉泉院), which is dedicated to Chen Tuan. Additionally atop the southern-most peak there is an ancient taoist temple which in modern times has been converted into a tea house.[3]

Ascent routes

There are three routes leading to Huashan's North Peak (1,614 m (5,295 ft)), the lowest of the mountain's five major peaks. The most popular is the traditional route in Hua Shan Yu (Hua Shan Gorge), first developed in the 3rd to 4th century A.D. and with successive expansion, mostly during the Tang Dynasty. It winds for 6 km from Huashan village to the north peak. A new route in Huang Pu Yu (Huang Pu Gorge, named after the hermit Huang Lu Zi who lived in this gorge in 8th century BC) follows the cable car to the North Peak, and is actually the ancient trail used prior to the Tang Dynasty, which has since fallen into disrepair. It had only been known to local villagers living nearby at the gorges since 1949, when a group of seven People's Liberation Army soldiers with a local guide used this route to climb to the North Peak and captured over 100 Kuomintang soldiers stationed on the North Peak and along the path of the traditional route. This trail is now known as "The Intelligent Take-over Route of Hua Shan", and was reinforced in early 2000. The Cable Car System stations are built next to the beginning and ends of this trail. A second cable car line, to the West Peak, was opened in 2013.

From the North Peak, a series of paths rise up to the Canglong Ling, which is a climb more than 300 m (984 ft) on top of a mountain ridge. This was the only trail to go to the four other peaks—the West Peak (2,038 m (6,686 ft)), the Center Peak (2,042 m (6,699 ft)), the East Peak (2,100 m (6,900 ft)) and the South Peak (2154.9m),[5]—until a new path was built to the east around the ridge in 1998.

Huashan has historically been a place of retreat for hardy hermits, whether Daoist, Buddhist or other; access to the mountain was only deliberately available to the strong-willed, or those who had found "the way". With greater mobility and prosperity, Chinese, particularly students, began to test their mettle and visit in the 1980s.

Fatalities

The inherent danger of many of the exposed, narrow pathways with precipitous drops gave the mountain a deserved reputation for danger. As tourism has boomed and the mountain's accessibility vastly improved with the installation of the cable car in the 1990s, visitor numbers have surged. Despite the safety measures introduced by cutting deeper pathways and building up stone steps and wider paths, as well as adding railings, fatalities continued to occur. The local government has proceeded to open new tracks and created one-way routes on some of the more hair-raising parts, such that the mountain can be scaled without extreme risk now, barring crowds and icy conditions. Some of the most precipitous tracks have actually been closed off. The former trail that led to the South Peak from the North Peak is on a cliff face, and it was known as being extremely dangerous; there is now a new and safer stone-built path to reach the South Peak temple, and on to the Peak itself.

Many Chinese still climb at nighttime, in order to reach the East Peak by dawn—though the mountain now has many hotels. This practice is a holdover from when it was considered safer to simply be unable to see the extreme danger of the tracks during the ascent, as well as to avoid meeting descending visitors at points where pathways have scarcely enough room for one visitor to pass through safely.

See also

References

Citations

Sources

- Goossaert, Vincent. "Huashan." in Fabrizio Pregadio, ed., The Encyclopedia of Taoism (London: Routledge, 2008), 481–482. TO FIX

- Harper, Damian. China. London: Lonely Planet, 2007.

- Palmer, Martin (October 26, 2006). "Religion and the Environment in China". Chinadialogue. Retrieved on 2008-08-27.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Hua Shan. |

| Wikivoyage has a travel guide for Mount Hua. |

.svg.png)