Temple du Marais

| Temple du Marais | |

|---|---|

| Eglise Protestante Unie du Marais | |

The Temple du Marais | |

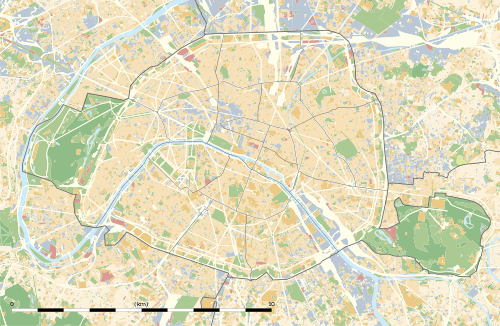

Temple du Marais The location of the Temple du Maris within Paris | |

| 48°51′12.1″N 2°21′58.5″E / 48.853361°N 2.366250°ECoordinates: 48°51′12.1″N 2°21′58.5″E / 48.853361°N 2.366250°E | |

| Location | Paris |

| Country | France |

| Denomination | United Protestant Church of France |

| Previous denomination | Reformed Church of France |

| Churchmanship | Evangelical[1] |

| Weekly attendance | 300[2] |

| Website |

eglisereformee |

| History | |

| Former name(s) | St. Mary of the Angels, Église Sainte-Marie-des-Anges |

| Authorising papal bull | 1626[3] |

| Founded | 1619 |

| Founder(s) | Francis de Sales, Jane Frances de Chantal |

| Events | Suppressed in the French Revolution and sold in 1796. Converted to a Protestant church in 1802 by decree of Napoléon Bonaparte.[4] |

| Architecture | |

| Status | Parish church |

| Functional status | Active |

| Heritage designation |

|

| Designated | 1887 as Temple Sainte-Marie |

| Architect(s) | François Mansart |

| Architectural type | Convent Church |

| Style | Baroque |

| Years built | 1632-1634 |

| Specifications | |

| Dome height (inner) | 108 feet (33 m) |

| Dome diameter (inner) | 44 feet (13 m) |

| Administration | |

| Synod | Synode régional d'Île-de-France |

| Clergy | |

| Pastor(s) | Gilles Boucomont, Caroline Bretones |

|

| |

The Temple du Marais, sometimes known as the Temple Sainte-Marie, or historically, as the Church of Sainte Marie de la Visitation, is a Protestant church located in the 4th arrondissement of Paris, in the district of Le Marais at 17 Rue Saint-Antoine. It was originally built as a Catholic convent by the Order of the Visitation of Holy Mary, whose sisters were commonly called the Visitandines. The church was closed in the French Revolution and later given to a Protestant congregation which continues its ministry to the present. The closest métro station is Bastille ![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

Catholic Convent

The Order of the Visitation of Holy Mary was founded in 1610 by Saint Francis de Sales and Saint Jane de Chantal in Annecy as a Catholic religious order of nuns. It started a convent in Paris in 1619 which built the current church and the crest of the order still surmounts the rose window above the entrance.[6] The building was designed by François Mansart in 1632, in the Baroque style. The church's benefactor, Noël Brûlart de Sillery, an admirer of the Pantheon in Rome, desired a centralized plan. Mansart, no doubt also influenced by the chapel of the Château d'Anet, delivered a highly original design with eight interconnected subsidiary spaces surrounding the central 44 feet (13 m) dome[7] including the sanctuary to the south, the vestibule to the north, three chapels, two sacrisites, and the nun's choir to the west. The design for the exterior was also quite original with the street elevation's three components, the arch with its Michelangelo inspired portal and projecting cross, the toit à l'impèriale with its lantern, and the cross-topped spire, drawing the eye heavenward.[8] The building's construction was overseen by the master mason contractor Michel Villedo.[9]

Saint Vincent de Paul served as the spiritual director of the convent for twenty-eight years.[10] The church crypt, finished in 1665, was the family mausoleum of Nicolas Fouquet, Superintendent of Finances for Louis XIV, whose remains were transferred to Paris a year after his death. The church is also home to the tomb of Henri, Marquis de Sévigné, husband of noted writer Marie de Rabutin-Chantal.[11]

In 1790 during the French Revolution the convent was seized, its furniture sold, and the building converted into storage for books seized from immigrants. In 1792 the sisters were expelled and the Society of Friends of the Law, led by the courtesan Theroigne de Mericourt, used the chapel for meetings. In 1796 the buildings were sold and all were later demolished apart from the chapel during the creation of the Rue Castex in 1805.[12] The Revolution left its mark on the chapel in the form of a Phrygian cap above a door.[13]

After the Revolution the sisters reconstituted their convent as the Monastère de la Visitation at 68 avenue Denfert-Rochereau were it continues to the present day.[14] The remains of the patron of the convent, Noël Brûlart de Sillery, as well as of the Bishop Frémiot were removed to the new location in 1836 rather than leave them in a Protestant church.[15]

Protestant Church

After the Concordat of 1801 the church was turned over, along with Saint-Louis-du-Louvre and the chapel of the Pentemont Abbey, for the use of Reformed believers in Paris who had been forced to worship in secret or in the chapels of foreign embassies since the Revocation of the Edict of Nantes in 1685. The first time that Pastor Paul-Henri Marron preached in the new church he remarked on how Protestants could now worship in freedom and security nestled between such symbols of the oppression of their forebears, the Bastille and the home of the Jesuits in the Lycée Charlemagne.[16]

The church was home to the famed city planner Georges-Eugène Haussmann and architect Victor Baltard during their student days at Collège Henri IV. While Baltard was a Lutheran he went with his more radical Protestant peers to the doctrinally stricter Calvinist church.[17] In 1830 the church held the state funeral for Benjamin Constant.[18]

The building was damaged in May, 1871 by fierce fighting at a barricade directly in front of the church during the Paris Commune.[19] Restoration work was undertaken in 1874 by Marcellin Varcollier and the statues on the pediment of charity and religion were carved by Ernest-Eugène Hiolle.[20] The church's organ was built by Joseph Merklin in 1895 with additional work by Haerpfer in 1960 and Heddelin in 1992.[21]

Elisée Lacheret became the pastor of the church in 1902 moving from the more theologically liberal l'Oratoire to the more evangelical Temple du Marais. As president of the permanent commission of the Reformed Church he played an important role during the debate that led to the Laïcité policy that separated church from state in France in 1905.[22] A plaque in the church commemorates his role in assuring the free practice of religion as well as in organizing the Eglises Réformées Evangéliques, the evangelical wing of the Reformed church.[23] During the World Wars the church crypt was used as a shelter from bombardment and under the German occupation of France during World War II the organ was used to hide Jews.[24]

The church continues as part of the United Protestant Church of France and has experienced a great revitalization in recent years going from a handful of congregants in 2004 to 300 weekly attenders, most under the age of 40, today.[25] There are French services at 10:30am on Sundays, an African community service (in French) at 1:00pm, a Japanese service at 4:00pm, and an Arabic service at 6:00pm. The congregation also holds many activities throughout the week including prayer and Bible study groups.[26] The church is open to tourists on Saturday afternoons from 3:30-5:30pm and volunteers provide tours.[27]

Gallery

Fighting directly in front of the church on May 25, 1871 during the Paris Commune

Fighting directly in front of the church on May 25, 1871 during the Paris Commune The church before restoration of the facade

The church before restoration of the facade- The door and pediment with the statues of charity (right) and religion (left) by Ernest-Eugène Hiolle

The church illuminated at night with the spire and the toit à l'impèriale rising behind the cross-topped arch

The church illuminated at night with the spire and the toit à l'impèriale rising behind the cross-topped arch An art performance during Nuit Blanche 2010

An art performance during Nuit Blanche 2010

References

- ↑ "Evangélisation". Temple du Marais.

- ↑ Salamon, Laure (September 27, 2013). "L'étonnant succès du temple du Marais". La Croix.

- ↑ Pernin, Raphael (1912). "Visitation Order". The Catholic Encyclopedia. New York: Robert Appleton. 15.

- ↑ Pénin, Marie-Christine. "Couvent des Filles de la Visitation Sainte-Marie de la rue Saint-Antoine". Tombes Sépultures dans les cimetières et autres lieux.

- ↑ "Temple du Marais ou temple Sainte-Marie (ancienne chapelle du couvent des filles de la Visitation dite église de la Visitation)". Monuments Historique. Ministère de la Culture.

- ↑ Pernin, Raphael (1912). "Visitation Order". The Catholic Encyclopedia. New York: Robert Appleton. 15.

- ↑ "Eglise Reformée du Marais". Paris Marais.

- ↑ Ayers, Andrew (2004). The Architecture of Paris: An Architectural Guide. Edition Axel Menges. p. 102. ISBN 978-3930698967.

- ↑ Pénin, Marie-Christine. "Couvent des Filles de la Visitation Sainte-Marie de la rue Saint-Antoine". Tombes Sépultures dans les cimetières et autres lieux.

- ↑ "Temples in Paris: Catholic churches and other places devoted to Protestant worship after the Concordat in 1801". Musée virtuel du Protestantisme.

- ↑ Pénin, Marie-Christine. "Couvent des Filles de la Visitation Sainte-Marie de la rue Saint-Antoine". Tombes Sépultures dans les cimetières et autres lieux.

- ↑ Ayers, Andrew (2004). The Architecture of Paris: An Architectural Guide. Edition Axel Menges. p. 102. ISBN 978-3930698967.

- ↑ "Temples in Paris: Catholic churches and other places devoted to Protestant worship after the Concordat in 1801". Musée virtuel du Protestantisme.

- ↑ "Monastère de la Visitation". Monastic Euro.

- ↑ Pénin, Marie-Christine. "Couvent des Filles de la Visitation Sainte-Marie de la rue Saint-Antoine". Tombes Sépultures dans les cimetières et autres lieux.

- ↑ Paris guide par les principaux écrivains et artistes de la France. Paris: A. Lacroix , Verboeckhoven. 1867. p. 766.

- ↑ Mead, Christopher Curtis (2012). Making Modern Paris: Victor Baltard's Central Markets and the Urban Practice of Architecture. University of Pennsylvania Press. p. 26.

- ↑ "Temples in Paris: Catholic churches and other places devoted to Protestant worship after the Concordat in 1801". Musée virtuel du Protestantisme.

- ↑ Villate, Laurent. Vivre et survivre dans le Marais. Editions Le Manuscrit. p. 239.

- ↑ "Eglise Reformée du Marais". Paris Marais.

- ↑ "Paris, temple Sainte Marie". Les Orgues de France.

- ↑ Harismendy, Patrick (2005). Les protestants et la séparation des Eglises et de l'Etat. Librairie Droz. p. 603ff.

- ↑ "Pasteur Elisée Lacheret". Site Pasteurs.

- ↑ "Un peu d'histoire sur le temple et ses pierres". Temple du Marais.

- ↑ Salamon, Laure (September 27, 2013). "L'étonnant succès du temple du Marais". La Croix.

- ↑ "News in English". Temple du Marais.

- ↑ "Un peu d'histoire sur le temple et ses pierres". Temple du Marais.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Temple du Marais. |

- Church website in English

- Video of the church's architecture

- An art performance in the church during Nuit Blanche 2010