Neanderthal anatomy

| Neanderthal Temporal range: Middle to Late Pleistocene, 0.6–0.03 Ma | |

|---|---|

| |

| Mounted Neanderthal skeleton, American Museum of Natural History | |

| Scientific classification | |

| Kingdom: | Animalia |

| Phylum: | Chordata |

| Class: | Mammalia |

| Order: | Primates |

| Family: | Hominidae |

| Genus: | Homo |

| Species: | H. neanderthalensis |

| Binomial name | |

| Homo neanderthalensis King, 1864 | |

| Synonyms | |

| |

Neanderthal anatomy differed from modern humans in that they had a more robust build and distinctive morphological features, especially on the cranium, which gradually accumulated more derived aspects, particularly in certain isolated geographic regions. Evidence suggests they were much stronger than modern humans[2] while they were comparable in height; based on 45 long bones from at most 14 males and 7 females, Neanderthal males averaged 164–168 cm (65–66 in) and females 152–156 cm (60–61 in) tall.[3] Samples of 26 specimens in 2010 found an average weight of 77.6 kg (171 lb) for males and 66.4 kg (146 lb) for females.[4] A 2007 genetic study suggested some Neanderthals may have had red hair.[5][6]

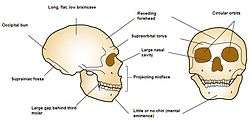

Distinguishing physical traits

The magnitude of autapomorphic traits in specimens differ in time. In the latest specimens, autapomorphy is unclear. The following is a list of physical traits that distinguish Neanderthals from modern humans. However, not all of them distinguish specific Neanderthal populations from various geographic areas, evolutionary periods, or other extinct humans. Also, many of these traits occasionally manifest in modern humans, particularly among certain ethnic groups traced to Neanderthal habitat ranges. Nothing is certain (from unearthed bones) about the shape of soft parts such as eyes, ears, and lips of Neanderthals.[8]

While the structure of the head and face were not very far removed from those of modern humans, there were still quite noticeable differences. Notably the neanderthal head is much longer, with a more pronounced facial front. The Neanderthal chin and forehead sloped backwards and the nose region protruded forward more than in modern humans. The common shapes of the nose are not known but in general it was likely more robust, and possibly slightly larger, than in modern humans. The brain space of the skull, and so most likely the brain itself, were larger than in modern humans.

When comparing traits to worldwide average present day human traits in Neanderthal specimens, the following traits are distinguished. The magnitude on particular trait changes with 300,000 years timeline. The large number of classic Neanderthal traits is significant because extreme examples of Homo sapiens may sometimes show one or more of these traits, but not most or all of them.

- Cranial

- Suprainiac fossa, a groove above the inion

- Occipital bun, a protuberance of the occipital bone, which looks like a hair knot[9]

- Projecting mid-face

- Less neotenized skull than modern humans[7]

- Low, flat, elongated skull

- A flat basicranium[10][11][12]

- Supraorbital torus, a prominent, trabecular (spongy) brow ridge

- 1,500–1,900 cm3 (92–116 cu in) skull capacity (modern man: 1425 cm3)

- Lack of a protruding chin (mental protuberance; although later specimens possess a slight protuberance)

- Crest on the mastoid process behind the ear opening

- No groove on canine teeth

- A retromolar space posterior to the third molar

- Bony projections on the sides of the nasal opening, projecting nose

- Distinctive shape of the bony labyrinth in the ear

- Larger mental foramen in mandible for facial blood supply

- Sub-cranial

- Considerably more robust, stronger build

- Long collar bones, wider shoulders

- Barrel-shaped rib cage

- Short, bowed shoulder blades

- More laterally curved radius with a radial tuberosity placed more medially, a longer radial neck, a more ovoid radial head, and a well-developed interosseous crest.[13]

- On the ulna, the trochlear notch is facing more anteriorly, the brachialis insertion is lower, the mid-shaft is larger, and the shaft is more sinusoidal.[13]

- Larger round finger tips

- Large kneecaps

- Thick, bowed shaft of the thigh bones, bowed femur

- Short shinbone and calf bone, longer torso and proportionally shorter legs

- Longer calcaneus (heel bone).[14]

- Long, gracile pelvic pubis (superior pubic ramus)

Cold-adapted theory

Some people thought that the big large Neanderthal noses were an adaptation to the cold,[15] but primate and arctic animal studies have shown sinus size reduction in areas of extreme cold rather than enlargement in accordance with Allen's rule.[16] Todd C. Rae summarizes explanations about Neanderthal anatomy as trying to find explanations for the "paradox" that their traits are not cold-adapted.[16] Therefore, Rae concludes that the design of the large and extensive Neanderthal nose was evolved for the hotter climate of the Middle East and went unchanged when the Neanderthals entered Europe.[16] However Neanderthals in Spain date back to 700 000 years, prior to them living in the Middle East.

Pathology

Within the west Asian and European record, there are five broad groups of pathology or injury noted in Neanderthal skeletons.

Fractures

Neanderthals seemed to suffer a high frequency of fractures, especially common on the ribs (Shanidar IV, La Chapelle-aux-Saints 1 'Old Man'), the femur (La Ferrassie 1), fibulae (La Ferrassie 2 and Tabun 1), spine (Kebara 2) and skull (Shanidar I, Krapina, Sala 1). These fractures are often healed and show little or no sign of infection, suggesting that injured individuals were cared for during times of incapacitation. It has been remarked that Neanderthals showed a frequency of such injuries comparable to that of modern rodeo professionals, showing frequent contact with large, combative mammals. The pattern of fractures, along with the absence of throwing weapons, suggests that they may have hunted by leaping onto their prey and stabbing or even wrestling it to the ground.[17]

Trauma

Particularly related to fractures are cases of trauma seen on many skeletons of Neanderthals. These usually take the form of stab wounds, as seen on Shanidar III, whose lung was probably punctured by a stab wound to the chest between the eighth and ninth ribs. This may have been an intentional attack or merely a hunting accident; either way the man survived for some weeks after his injury before being killed by a rock fall in the Shanidar cave. Other signs of trauma include blows to the head (Shanidar I and IV, Krapina), all of which seemed to have healed, although traces of the scalp wounds are visible on the surface of the skulls.

Degenerative disease

Arthritis was common in the older Neanderthal population, specifically targeting areas of articulation such as the ankle (Shanidar III), spine and hips (La Chapelle-aux-Saints 'Old Man'), arms (La Quina 5, Krapina, Feldhofer) knees, fingers and toes. This is closely related to degenerative joint disease, which can range from normal, use-related degeneration to painful, debilitating restriction of movement and deformity and is seen in varying degree in the Shanidar skeletons (I–IV).

Developmental Stress

.jpg)

Two non-specific indicators of stress during development are found in teeth, which record stresses, such as periods of food scarcity or illness, that disrupt normal dental growth. One indicator is enamel hypoplasia, which appears as pits, grooves, or lines in the hard enamel covering of teeth. The other indicator, fluctuating asymmetry, manifests as random departures from symmetry in paired biological structures (such as right and left teeth). Teeth do not grow in size after they form nor do they produce new enamel, so enamel hypoplasia and fluctuating asymmetry provide a permanent record of developmental stresses occurring in infancy and childhood. A study of 669 Neanderthal crowns showed that 75% of individuals suffered some degree of hypoplasia. Two studies,[18][19] compared Neanderthals with the Tigara, coastal whale-hunting people from Point Hope Alaska, finding comparable levels of linear enamel hypoplasia (a specific form of hypoplasia) and higher levels of fluctuating asymmetry in Neanderthals. Estimated stress episode duration from Neanderthal linear enamel hyoplasias suggest that Neandertals experienced stresses lasting from two weeks to up to three months.

Infection

Evidence of infections on Neanderthal skeletons is usually visible in the form of lesions on the bone, which are created by systemic infection on areas closest to the bone. Shanidar I has evidence of the degenerative lesions as does La Ferrassie 1, whose lesions on both femora, tibiae and fibulae are indicative of a systemic infection or carcinoma (malignant tumour/cancer).

Childhood

Neanderthal children may have grown faster than modern human children. Modern humans have the slowest body growth of any mammal during childhood (the period between infancy and puberty) with lack of growth during this period being made up later in an adolescent growth spurt.[20][21][22] The possibility that Neanderthal childhood growth was different was first raised in 1928 by the excavators of the Mousterian rock-shelter of a Neanderthal juvenile.[23] Arthur Keith in 1931 wrote, "Apparently Neanderthal children assumed the appearances of maturity at an earlier age than modern children."[24] The rate of body maturation can be inferred by comparing the maturity of a juvenile's fossil remains and the estimated age of death.

The age at which juveniles die can be indirectly inferred from their tooth morphology, development and emergence. This has been argued to both support[25] and question[26][27] the existence of a maturation difference between Neanderthals and modern humans. Since 2007, tooth age can be directly calculated using the noninvasive imaging of growth patterns in tooth enamel by means of x-ray synchrotron microtomography.[28]

This research supports the occurrence of much more rapid physical development in Neanderthals than in modern human children.[29] The x-ray synchrotron microtomography study of early H. sapiens sapiens argues that this difference existed between the two species as far back as 160,000 years before present.[30]

Footnotes

- ↑ Bibliography of Fossil Vertebrates 1954-1958 - C.L. Camp, H.J. Allison, and R.H. Nichols - Google Books. Books.google.ca. Retrieved on 2014-05-24.

- ↑ "Neanderthal". BBC. Retrieved 18 May 2009.

- ↑ Helmuth H (1998). "Body height, body mass and surface area of the Neanderthals". Zeitschrift für Morphologie und Anthropologie. 82 (1): 1–12. PMID 9850627.

- ↑ Froehle, Andrew W; Churchill, Steven E (2009). "Energetic Competition Between Neandertals and Anatomically Modern Humans" (PDF). PaleoAnthropology: 96–116. Retrieved 2011-10-31.

- ↑ Laleuza-Fox, Carles; Holger Römpler; et al. (2007-10-25). "A Melanocortin 1 Receptor Allele Suggests Varying Pigmentation Among Neanderthals". Science. 318 (5855): 1453–5. doi:10.1126/science.1147417. PMID 17962522.

- ↑ Rincon, Paul (25 October 2007). "Neanderthals 'were flame-haired'". BBC News. Retrieved 25 October 2007.

- 1 2 Montagu, A. (1989). Growing Young. Bergin & Garvey: CT.

- ↑ Sawyer GJ, Maley B (March 2005). "Neanderthal reconstructed". The Anatomical Record Part B: The New Anatomist. 283 (1): 23–31. doi:10.1002/ar.b.20057. PMID 15761833. Lay summary – LiveScience (March 10, 2005).

- ↑ Gunz P, Harvati K (March 2007). "The Neanderthal 'chignon': variation, integration, and homology". Journal of Human Evolution. 52 (3): 262–74. doi:10.1016/j.jhevol.2006.08.010. PMID 17097133.

- ↑ http://www.pajamacore.org/writings/origins.php

- ↑ Bower, Bruce (11 April 1992). "Neanderthals to investigators: can we talk? – vocal abilities in pre-historic humans". Science News. Retrieved 29 Apr 2014.

- ↑ Arensburg B, Schepartz LA, Tillier AM, Vandermeersch B, Rak Y (October 1990). "A reappraisal of the anatomical basis for speech in Middle Palaeolithic hominids". American Journal of Physical Anthropology. 83 (2): 137–46. doi:10.1002/ajpa.1330830202. PMID 2248373.

- 1 2 De Groote I (October 2011). "The Neanderthal lower arm". Journal of Human Evolution. 61 (4): 396–410. doi:10.1016/j.jhevol.2011.05.007. PMID 21762953.

- ↑ Edwards, Lin (7 February 2011). "Early humans won at running; Neandertals won at walking". phys.org.

- ↑ Finlayson, C (2004). Neanderthals and modern humans: an ecological and evolutionary perspective. Cambridge University Press. pp. 84. ISBN 0-521-82087-1.

- 1 2 3 Rae TC, Koppe T, Stringer CB (February 2011). "The Neanderthal face is not cold adapted". Journal of Human Evolution. 60 (2): 234–9. doi:10.1016/j.jhevol.2010.10.003. PMID 21183202.

- ↑ T.D. Berger & E. Trinkaus (1995). "Patterns of trauma among Neadertals". Journal of Archaeological Science. 22 (6): 841–852. doi:10.1016/0305-4403(95)90013-6. Retrieved 2007-06-28.

- ↑ Guatelli-Steinberg D, Larsen CS, Hutchinson DL (2004). "Prevalence and the duration of linear enamel hypoplasia: a comparative study of Neandertals and Inuit foragers". Journal of Human Evolution. 47 (1-2): 65–84. doi:10.1016/j.jhevol.2004.05.004. PMID 15288524.

- ↑ Barrett CK, Guatelli-Steinberg D, Sciulli PW (October 2012). "Revisiting dental fluctuating asymmetry in neandertals and modern humans". American Journal of Physical Anthropology. 149 (2): 193–204. doi:10.1002/ajpa.22107. PMID 22791408.

- ↑ Walker R, Hill K, Burger O, Hurtado AM (April 2006). "Life in the slow lane revisited: ontogenetic separation between chimpanzees and humans". American Journal of Physical Anthropology. 129 (4): 577–83. doi:10.1002/ajpa.20306. PMID 16345067.

- ↑ Bogin, Barry (1997). m682 "Evolutionary hypotheses for human childhood" Check

|url=value (help). American Journal of Physical Anthropology. 104 (S25): 63–89. doi:10.1002/(SICI)1096-8644(1997)25+<63::AID-AJPA3>3.0.CO;2-8. - ↑ Bogin, Barry (1999). Patterns of human growth. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 0-521-56438-7. OCLC 39692257.

- ↑ Garrod, D. A. E., Buxton, L. H. D., Elliot-Smith, G., Bate, D.M. A. (1928). "Excavation of a Mousterian rock-shelter at Devil's Tower, Gibraltar". Journal of the Royal Anthropological Institute. 58: 33–113. JSTOR 4619528.

- ↑ Keith, Arthur (1931). New discoveries relating to the antiquity of man. London: W. W. Norton & Company. p. 346. OCLC 3665578.

- ↑ Ramirez Rozzi FV, Bermudez De Castro JM (April 2004). "Surprisingly rapid growth in Neanderthals". Nature. 428 (6986): 936–9. doi:10.1038/nature02428. PMID 15118725.

- ↑ Macchiarelli R, Bondioli L, Debénath A, et al. (December 2006). "How Neanderthal molar teeth grew". Nature. 444 (7120): 748–51. doi:10.1038/nature05314. PMID 17122777.

- ↑ Guatelli-Steinberg D, Reid DJ, Bishop TA, Larsen CS (October 2005). "Anterior tooth growth periods in Neandertals were comparable to those of modern humans". Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 102 (40): 14197–202. doi:10.1073/pnas.0503108102. PMC 1242286

. PMID 16183746.

. PMID 16183746. - ↑ Tafforeau P, Smith TM (February 2008). "Nondestructive imaging of hominoid dental microstructure using phase contrast X-ray synchrotron microtomography". Journal of Human Evolution. 54 (2): 272–8. doi:10.1016/j.jhevol.2007.09.018. PMID 18045654.

- ↑ Smith TM, Toussaint M, Reid DJ, Olejniczak AJ, Hublin JJ (December 2007). "Rapid dental development in a Middle Paleolithic Belgian Neanderthal". Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 104 (51): 20220–5. doi:10.1073/pnas.0707051104. PMC 2154412

. PMID 18077342.

. PMID 18077342. - ↑ Smith TM, Tafforeau P, Reid DJ, et al. (April 2007). "Earliest evidence of modern human life history in North African early Homo sapiens". Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 104 (15): 6128–33. doi:10.1073/pnas.0700747104. PMC 1828706

. PMID 17372199.

. PMID 17372199.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Homo neanderthalensis. |

| Wikibooks has a book on the topic of: Introduction to Paleoanthropology |

| Wikispecies has information related to: Homo neanderthalensis |