Norman Cross

Norman Cross lies near Peterborough, Cambridgeshire. Traditionally in Huntingdonshire, it gave its name to a hundred and, from 1894 to 1974, Norman Cross Rural District. The junction of the A1 and A15 roads is here.

It was the site of the world's first purpose-built prisoner-of-war camp[1] or "depot" built during the Napoleonic Wars by the Navy.

Design and construction of prison camp

The Royal Navy Transport Board was responsible for the care of prisoners of war. When Sir Ralph Abercromby communicated in 1796 that he was transferring 4,000 prisoners from the West Indies, the Board began the search for a site for a new prison. The site was chosen because it was on the Great North Road only 76 miles (122 km) from London and was deemed far enough from the coast that escaped prisoners could not flee back to France. The site had a good water supply and close to sufficient local sources of food to sustain many thousands of prisoners and the guards. Work commenced in December 1796 with much of the timber building prefabricated in London and assembled on site. 500 carpenters and labourers worked on the site for 3 months. The cost of construction was £34,581 11s 3d.

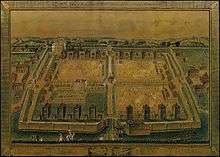

The design of the prison was based on that of a contemporary artillery fort. A ditch 27 feet (8.2 m) deep (to prevent prisoners tunnelling out) was placed inside the wall (originally a wooden stockade fence, replaced with a brick wall in 1805) and guarded by 'silent sentries' who could not be seen by the prisoners. The barracks for the garrison were placed outside and a large guard house (known as the Block House) containing troops and six cannon was placed right at the centre. The interior of the prison was divided into four quadrangles, each with four double storey wooden accommodation blocks for 500 prisoners and four ablutions blocks. One accommodation block was reserved for officers. Half of each quadrangle was a large exercise yard. The north east quadrangle contained the prison hospital. There was also a windowless block known as the Black Hole in which prisoners were kept shackled on half rations as punishment, mainly for violence towards the guards although two prisoners were sent to the Black Hole for "infamous vices".[2] 30 wells were sunk to draw drinking water for the prisoners and garrison.

Operation

The average prison population was about 5,500 men. The lowest number recorded was 3,300 in October 1804 and 6,272 on 10 April 1810 was the highest number of prisoners recorded in any official document.[2]

Norman Cross was intended to be a model depot providing the most humane treatment of prisoners of war.

Most of the men held in the prison were low-ranking soldiers and sailors, including midshipmen and junior officers, with a small number of privateers. About 100 senior officers and some civilians "of good social standing", mainly passengers on captured ships and the wives of some officers, were given parole d'honneur outside the prison, mainly in Peterborough although some as far away as Northampton, Plymouth, Melrose and Abergavenny.[2] They were afforded the courtesy of their rank within English society. Some "with good private means" hired servants and often dined out while wearing full uniform.[2] Three French officers died of natural causes while on parole and were buried with full military honours.[2] Four French officers and five Dutch officers married English women while on parole.[2] The most senior officer on parole from the prison was General Charles Lefebvre-Desnouettes who resided with his wife in Cheltenham from 1809 until they escaped back to France in 1811.

Clothing

The French prisoners, whose main pastime was gambling, were accused by the British government of selling their clothes and few personal possessions to raise money for further gambling. In 1801, the British government issued statements blaming the French Consul for not supplying sufficient clothing (the British government had paid the French for all English prisoners held in France and French colonies to be clothed).

Samuel Johnson and a Mr Serle, who visited the barracks, compiled a report on behalf of the British government, stating that the proportion of food allowance was fully sufficient to maintain both life and health, but added: "provided it is not shamefully lost by gambling." The Lords of the Admiralty, along with Doctor Johnson, instructed that naked prisoners should be clothed at once, without waiting for the French supply or payment for clothing.

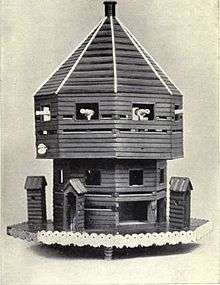

The British government provided each naked prisoner with a yellow suit, a grey or yellow cap, a yellow jacket, a red waistcoat, yellow trousers, a neckerchief, two shirts, two pairs of stockings, and one pair of shoes. The bright colours were chosen to aid the recognition of escaped prisoners. In Foulley's model of the prison (pictured right) more than half the prisoners are represented wearing these clothes.

Food

Food was prepared by cooks drawn from the prison ranks. The cooks, one for every 12 prisoners, were paid a small allowance by the British government. The initial daily food ration for each prisoner was 1 lb of beef, 1 lb of bread, 1 lb of potatoes, and 1 lb of cabbage or pease. As the majority of prisoners were Roman Catholic, herrings or cod was substituted for beef on Fridays. Each prisoner was also allowed 2oz of soap per week. In November 1797 the British and French governments agreed that each should feed their own citizens in their enemy's prisons. The French provided a daily ration of 1 pint of beer, 8oz of beef or fish, 26oz of bread, 2oz of cheese and 1 lb of potato or fresh vegetables. They were also allowed 1 lb of soap and 1 lb of tobacco per month. Patients in the prison hospital were given a daily ration of 1 pint of tea morning and evening, 16oz of bread, 16oz of beef, mutton or fish, 1 pint of broth, 16oz of green vegetables or potato, and 2 pints of beer.

The British government went to great lengths to provide food of a quality at least equal to that available to locals. The senior officer from each quadrangle was permitted to inspect the food as it was delivered to the prison to ensure it was of sufficient quality.[2]

Despite the generous supply and quality of food, some prisoners died of starvation after gambling away their rations.[2]

Education

Most prisoners were illiterate and were offered the opportunity to learn to read and write in their native language and English. Prisoners who could read were given access to books. News on the progress of the war, including successes and defeats on both sides, was reported to prisoners.

In July 1799, Dutch prisoners sought permission to use one building as a theatre. The Sea Lords refused. However Foulley's model, depicting the prison as it was in about 1809, shows a theatre in the south west quadrangle.

Religion

There was no prison chapel but a Catholic priest resided in the garrison barracks. From 1808, Stephen John Baptist Lewis de Galois de la Tours, the former Bishop of Moulins who was expelled from France in 1791 and lived a mile from the prison at Stilton, was permitted by the Admiralty to minister and provide charity to the prisoners at his own expense.[2]

Health

Sick prisoners were initially treated in the prison hospital by two French navy surgeons and 24 orderlies.[2]

As the number of prisoners increased, disease spread throughout the camp. 1,020 prisoners died in a typhus outbreak in 1800–1801.[2] A special 'typhus cemetery' was dug near the camp.[3]

Leonard Gillespie, Surgeon to the Fleet, wrote in 1804 that pneumonia was common with some cases becoming fatal carditis.[4] There were also many cases of consumption. A brick house for a resident British surgeon was built adjacent to the prison hospital in 1805.[3]

A peculiar outbreak of Nyctalopia or night-blindness affected many of the prisoners in 1806. They became severely dyspeptic and completely blind from sunset until dawn, to the extent that their fitter companions had to lead them around the camp. Various treatments were tried and failed; finally they were cured with black hellebore, given as snuff, which relieved the dyspepsia and restored their night vision within a few days.[5]

A total of 1,770 prisoner deaths from disease were recorded during the time the prison was in operation, although the records are incomplete.[2]

Craft and prison economy

At the outbreak of the war, the Transport Board wrote that "the prisoners in all the depots in the country are at full liberty to exercise their industry within the prisons, in manufacturing and selling any articles they may think proper excepting those which would affect the Revenue in opposition to the Laws, obscene toys and drawings, or articles made either from their clothing or the prison stores".

Many prisoners at Norman Cross made artefacts such as toys, model ships and dominoes sets from carved wood or animal bone, and straw marquetry. Examples of the prisoners' craftwork were sold to visitors and passers by. Some highly skilled prisoners were commissioned by wealthy individuals, some of the prisoners becoming very rich in the process.[6] Archdeacon William Strong, a regular visitor to the prison, notes in his diary of 23 October 1801 that he provided a piece of mahogany and paid a prisoner £1 15s 6d to build a model of the Block House and £2 2s for a straw picture of Peterborough Cathedral.[2]

Prisoners were permitted to sell artefacts twice a week at the local market, or daily at the prison gate. Prices were regulated so the prisoners did not undersell local industries. In return, prisoners were permitted to buy additional food, tobacco, wine, clothes or materials for further work.

At the end of the war, the Transport Board noted that some prisoners had earned as much as 100 guineas.

Thousands of Norman Cross artefacts survive today in local museums, including 500 in Peterborough Museum, and private collections. A collection of model ships made at Norman Cross is on display at Arlington Court in Devon.

During December 1804, prisoners Nicholas Deschamps and Jean Roubillard were discovered forging £1 notes. Engraved plates of a very high standard and printing implements were found. The prisoners were convicted of forgery at the Huntingdon Assizes. Forging banknotes was a capital offence at the time. They were sentenced to death but this was commuted. They remained in Huntingdon Gaol until they were repatriated to France in 1814.

Insubordination and escapes

Insubordination was rife among prisoners. A force of Shropshire militia, a battalion of army reserve and a volunteer force from Peterborough were required to restrain the prisoners from breaking out during a particular period of defiance.

Six prisoners escaped in April 1801. Three of them were caught at Boston, Lincolnshire and the remaining three were caught in a fishing boat off the Norfolk coast. Each year the number of attempts to escape increased, as did the numbers in each escape. Three groups of 16 men each escaped in late 1801.

Incomplete tunnels were discovered in 1802.

After two major escape attempts in 1804 and 1807, the wooden stockade fence was replaced with a brick wall.[3]

One prisoner, Charles Francois Bourchier, stabbed a civilian Alexander Halliday while attempting to escape on 9 September 1808. He was convicted at the Huntingdon Assizes and sentenced to death by hanging. He was executed at the prison in front of the prisoners and the whole garrison. This was the only civil execution at Norman Cross.[2] After the stabbing, the entire prison was searched and 700 daggers were found.[2]

In January 1812, a French prisoner was shot whilst escaping after he had overpowered a guard and stolen a bayonet.

During August 1813, escaped prisoners from Norman Cross were discovered as far away as Hampshire.

Repatriation

Peace was finally proclaimed with France in 1814, following Napoleon's defeat and consequent abdication. The prisoners, the garrison guards and local people joined together in celebrations. The remaining prisoners left the garrison by June of that year. A few decided to remain in England and settled near Yaxley and Stilton.

Demolition

The wooden buildings were dismantled in June 1816 and the parts sold at auction. Some of the buildings were relocated to nearby towns although much of the timber structures were sold as firewood.

The commander of the depot was the Agent and his house survives. The restored stables of the Norman Cross Depot is now the Norman Cross Gallery a privately owned art gallery.

Memorial

The memorial to the 1,770 prisoners who died at Norman Cross was erected in 1914 by the Entente Cordiale Society beside the Great North Road.[7] The bronze Imperial Eagle was stolen in 1990, but replaced with a new one in 2005 following a fundraising appeal.[8]

When a section of the A1 was upgraded to motorway standard in 1998[9] the memorial required relocating.[10] On 2 April 2005, the Duke of Wellington, a patron of the appeal, unveiled the restored memorial on a new site beside the A15. A replacement bronze eagle, sculpted by John Doubleday, was placed on the re-sited column.

Study

An archaeological dig was carried out on part of the site and was an episode of the Channel 4 series Time Team in 2009. Part of the wall, an accommodation block, ablution hut and burial ground were uncovered. The site is considered of national importance and has been classified as a scheduled ancient monument.[11]

References

- ↑ "Time Team help unearth world's first prisoner of war camp". Daily Mail. 22 July 2009.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 Thomas James Walker (1913). The depot for prisoners of war at Norman Cross, Huntingdonshire, 1796 to 1816. Constable & Company.

- 1 2 3 Norman Cross Camp Cambridgeshire. Archaeological Evaluation and Assessment of Results, [Wessex Archaeology], September 2010

- ↑ Gillespie, Leonard (1804). "Short Statement of the Result of the Practice in the Hospital for Prisoners of War at Norman Cross". The London medical and physical journal. 12: 345–347.

- ↑ Waller, John Augustine, British Domestic Herbal, 1822, quoted in Barton, Benjamin Herbert & Castle, Thomas, The British Flora Medica; or, History of the Medicinal Plants of Great Britain, London, 1837; Google books online version

- ↑ Jane A. Kimball (2004). Trench art: an illustrated history. Silverpenny Press.

- ↑ Historic England. "Monument 1/4 mile north of Norman Cross (1222028)". National Heritage List for England.

- ↑ Friends of Norman Cross. The Eagle Stolen, 1990, and The Appeal, 1991, retrieved January 2, 2014

- ↑ "A1(M) Alconbury to Peterborough". Highways Agency.

- ↑ "Norman Cross Eagle Appeal". Local Heritage Initiative. Retrieved 22 January 2008.

- ↑ Historic England. "Site of Napoleonic Prisoners of War Camp, Norman Cross (1006782)". National Heritage List for England.

External links

- Friends of Norman Cross

- Time Team Series 17: Death and Dominoes – The First POW Camp (Norman Cross, Cambridgeshire), Wessex Archaeology.

- Norman Cross, Cambridgeshire Flickr collection

- Walker, Thomas James, The Depot for Prisoners of War at Norman Cross, Huntingdonshire, 1796 to 1816, London, Constable, 1913 E-book version (very poorly proof-read)

Coordinates: 52°30′14″N 0°17′27″W / 52.503836°N 0.290824°W