North Uist

| Gaelic name |

|

|---|---|

| Meaning of name | Unclear |

| Location | |

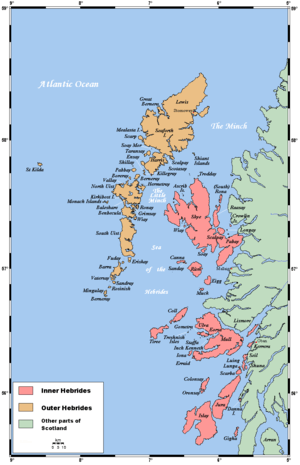

North Uist North Uist shown within the Outer Hebrides | |

| OS grid reference | NF835697 |

| Physical geography | |

| Island group | Uists and Barra |

| Area | 30,305 hectares (117 sq mi) |

| Area rank | 10 [1] |

| Highest elevation | Eaval 1,138 ft (347 m) |

| Administration | |

| Sovereign state | United Kingdom |

| Country | Scotland |

| Council area | Na h-Eileanan Siar |

| Demographics | |

| Population | 1,254[2] |

| Population rank | 12 [1] |

| Pop. density | 4.14 people/km2[2][3] |

| Largest settlement | Lochmaddy |

| References | [3][4][5][6] |

North Uist (Scottish Gaelic: Uibhist a Tuath pronounced [ˈɯ.ɪʃtʲ ə t̪ʰuə]) is an island and community in the Outer Hebrides of Scotland.

Gaelic

According to the 2011 Census, there are 887 Gaelic speakers (61%) on North Uist.[7]

Geography

North Uist is the tenth largest Scottish island[8] and the thirteenth largest island surrounding Great Britain.[9] It has an area of 117 square miles (303 km2),[3] slightly smaller than South Uist. North Uist is connected by causeways to Benbecula via Grimsay, to Berneray, and to Baleshare. With the exception of the south east, the island is very flat, and covered with a patchwork of peat bogs, low hills and lochans, with more than half the land being covered by water. Some of the lochs contain a mixture of fresh and tidal salt water, giving rise to some complex and unusual habitats. Loch Sgadabhagh, about which it has been said "there is probably no other loch in Britain which approaches Loch Scadavay in irregularity and complexity of outline", is the largest loch by area on North Uist although Loch Obisary has about twice the volume of water.[10] The northern part of the island is part of the South Lewis, Harris and North Uist National Scenic Area, one of 40 in Scotland.[11]

Settlements

The main settlement on the island is Lochmaddy, a fishing port and home to a museum, an arts centre and a camera obscura. Caledonian MacBrayne ferries sail from the village to Uig on Skye, as well as from the island of Berneray (which is connected to North Uist by road causeway), to Leverburgh in Harris. Lochmaddy also has Taigh Chearsabhagh - a museum and arts centre with a cafe, small shop and post office service. Nearby is the Uist Outdoor Centre.

The island's main villages are Sollas, Hosta, Tigharry, Hougharry, Paible, Grimsay and Cladach Kirkibost. Other settlements include Clachan Carinish, Knockquien, Port nan Long, Greinetobht and Scolpaig, home to the nineteenth century Scolpaig Tower folly. Loch Portain is a small hamlet on the east coast – some 9 miles (14 km) from Lochmaddy, with sub areas of Cheesebay and Hoebeg.

According to the 2001 census North Uist had a population of 1,271 (1,320 including Baleshare).[12]

Places of interest

North Uist has many prehistoric structures, including the Barpa Langass chambered cairn, the Pobull Fhinn stone circle, the Fir Bhreige standing stones, the islet of Eilean Dòmhnuill (which may be the earliest crannog site in Scotland),[13] and the Baile Sear roundhouses, which were exposed by storms in January, 2005.[14]

The Vikings arrived in the Hebrides in 800AD where they had large settlements.

The island is known for its birdlife, including corncrakes, Arctic terns, gannets, corn buntings and Manx shearwaters. The RSPB has a nature reserve at Balranald.[15]

Despite limited facilities, the island's athletics club (North Uist Amateur Athletics Club) has performed well at local, regional and national athletics competitions.

Etymology

In Donald Munro's A Description of the Western Isles of Scotland Called Hybrides of 1549, North Uist, Benbecula and South Uist are described as one island of Ywst (Uist). Starting in the south of this 'island', he described the division between South Uist and Benbecula where "the end heirof the sea enters, and cuts the countrey be ebbing and flowing through it". Further north of Benbecula he described North Uist as "this countrey is called Kenehnache of Ywst, that is in Englishe, the north head of Ywst".[16]

Some have given the etymology of Uist from Old Norse meaning "west",[3] much like Westray in the Orkney Islands.[17] Another speculated derivation from Uist in Old Norse is Ivist,[5] derived from vist meaning "an abode, dwelling, domicile".[18]

A Gaelic etymology is also possible, with I-fheirste meaning "Crossings-island" or "Fords-island", derived from I meaning "island" and fearsad meaning "estuary, sand-bank, passage across at ebb-tide".[17][19] Place-names derived from fearsad include Fersit, and Belfast.[19] Mac an Tàilleir (2003) suggests that a Gaelic derivation of Uist may be "corn island".[20] However, whilst noting that the vist ending would have been familiar to speakers of Old Norse as meaning "dwelling" Gammeltoft (2007) states the word is "of non-Gaelic origin" and that it reveals itself as one of a number of "foreign place-names having undergone adaptation in Old Norse".[21]

Population

In the eighteenth century the total population of the combined Uists rose dramatically, before the population crash of the Highland Clearances. In 1755, there was an estimated combined population on the Uists, of 4,118; by 1794 it rose to 6,668; and in 1821 to 11,009.[3]

North Uist

The pre-clearance population of North Uist was about 5,000 and it has dwindled to about 1,300 people in 2001.

| | | | | | | | |

From Haswell-Smith (2004)[3] except as stated.

History

After the Norse occupation of the Western Isles the MacRuairidhs controlled the island.[3] North Uist was granted to Macdonald of Sleat in 1495, and remained in possession of the Macdonalds of Sleat until 1855, when it was sold to Sir John Powlett Orde.[22] Today the island is owned by the Granville family through the North Uist Trust.[22]

North Uist and the Clearances

North Uist was hit hard during the Highland Clearances, and there was large scale emigration from the island to Cape Breton, Nova Scotia, Canada.[23] The pre-clearance population of North Uist had been almost 5,000,[22] though by 1841 it had fallen to 3,870, and has further dwindled to about 1,300 people today. The clearances occurred later on North Uist, which was predominately Presbyterian, than on South Uist which was mostly Roman Catholic.[23]

The main reason for the massive scale of emigration was the failure of the island's kelp industry. Since the French Revolutionary Wars the kelp industry had been North Uist's main source of income.[23] Though with the collapse of their main source of income the crofters of North Uist could not afford the high rents.[23] Even as the landlords reduced the rents, such as in 1827 when the rents were reduced by 20%, many crofters were forced to emigrate.[23]

The first real clearances on North Uist occurred in the 1820s.[23] In 1826 the villages of Kyles Berneray, Baile Mhic Phail and Baile mhic Conon, located on the north-east corner of North Uist, were cleared of their inhabitants. Although some moved further east to Loch Portain, most of those affected moved to Cape Breton, Nova Scotia.[23] The effect of this is shown in the rental roll of 1827, which states that over fifty families had "Gone to America", meaning Cape Breton.[23] As the economic conditions worsened and with reports of islanders succeeding overseas, the numbers of families emigrating from Scotland to North America greatly increased.[23] In 1838 1,300 people from North Uist were recorded as being cleared. It is misconception that most families involved in the clearances were "cleared" from their holdings, though in 1849 there was rioting as 603 inhabitants from Sollas were forcefully cleared by Lord (the 4th Baron) Macdonald.[24] In the incident the women of Sollas took large part in the rioting.[25] As a detachment of Glasgow police officers advanced on the protesters, the Sollas men were said to have stood aside, but the women of Sollas stood up to the authorities, and pelted the police with rocks. The police then descended upon the Sollas folk and attacked them with their truncheons.[26] In fact a Hebredian settlement in Cape Breton County, Nova Scotia was originally called Sollas (now Woodbine).[27][28] North Uist surnames affected during the clearances were the MacAulays, Morrisons, MacCodrums, MacCuishs, and MacDonalds.[23]

Famous residents

- The Scottish Gaelic poet Dòmhnall Ruadh Chorùna (1887–1967) was born on North Uist and lived his life there. Due to his vivid descriptions of his experiences in the First World War, he is often referred to as "The Voice of the Trenches."

- Erskine Beveridge, LL.D., FRSE (1851–1920), a textile manufacturer and antiquary and sometime resident of Vallay, completed important archaeological excavations in the Hebrides.

- Julie Fowlis (born 1979), a singer and instrumentalist who sings primarily in Scottish Gaelic, was born and raised on North Uist.

- Alasdair Morrison (born 1968), former Member of the Scottish Parliament for the Western Isles, lived on North Uist and was educated at Paible School.

- Flight Lieutenant John Morrison, 2nd Viscount Dunrossil, CMG, JP (1926–2000), diplomat and Governor of Bermuda, lived at Clachan Sands.

- Pauline Prior-Pitt, a British poet, lives on North Uist.

- Brothers Rory and Calum MacDonald, members of the Gaelic rock band Runrig

- Angus MacAskill, largest "true giant" and strongest man who ever lived from Berneray, off North Uist

Footnotes

- 1 2 Area and population ranks: there are c. 300 islands over 20 ha in extent and 93 permanently inhabited islands were listed in the 2011 census.

- 1 2 3 National Records of Scotland (15 August 2013) (pdf) Statistical Bulletin: 2011 Census: First Results on Population and Household Estimates for Scotland - Release 1C (Part Two). "Appendix 2: Population and households on Scotland’s inhabited islands". Retrieved 17 August 2013.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 Haswell-Smith, Hamish (2004). The Scottish Islands. Edinburgh: Canongate. ISBN 978-1-84195-454-7.

- ↑ Ordnance Survey. Get-a-map (Map). 1:25,000. Leisure. Ordinance Survey. Retrieved 21 August 2013.

- 1 2 edited by Munch & Goss (1874). "The Chronicles of Mann vol 22.". Isle of Man: Manx Society. Retrieved 31 October 2007.

- ↑ Geir T. Zoëga (1910). "A Concise Dictionary of Old Icelandic". Germanic Lexicon Project. Retrieved 4 July 2007.

- ↑ Census 2011 stats BBC News. Retrieved 20 April 2014.

- ↑ List of islands of Scotland

- ↑ List of European islands by area

- ↑ Murray and Pullar (1908) "Lochs of North Uist" Pages 188–89, Volume II, Part II. National Library of Scotland. Retrieved 20 December 2009.

- ↑ "National Scenic Areas". SNH. Retrieved 30 Mar 2011.

- 1 2 "Number of residents and households in all inhabited islands" (PDF). General Register Office for Scotland. Retrieved 17 October 2007.

- ↑ Armit, Ian (1998). Scotland's Hidden History. Stroud, Gloucestershire: Tempus. ISBN 0-7524-1400-3.

- ↑ Ross, John (11 July 2007). "Race to study Iron Age roundhouses before they are lost to sea storms". The Scotsman. Retrieved 4 December 2007.

- ↑ "Wildlife and habitats of Uist". Scottish Natural Heritage. Retrieved 6 January 2008.

- ↑ A Description of the Western Isles of Scotland Called Hybrides; Monro, Donald, 1549

- 1 2 Thomas, F. W. L. "Did the Northmen extirpate the Celtic Inhabitants of the Hebrides in the Ninth Century?". Proc. Soc. of Antiq. Scot. 11: 475–476.

- ↑ Cleasby, Richard & Vigfusson, Gudbrand (1874). "An Icelandic-English dictionary". Germanic Lexicon Project. p. 711. Retrieved 6 January 2008.

- 1 2 "An Etymological Dictionary of the Gaelic Language". Retrieved 31 October 2007.

- ↑ Mac an Tàilleir (2003) p. 116

- ↑ Gammeltoft, Peder "Scandinavian Naming-Systems in the Hebrides—A Way of Understanding how the Scandinavians were in Contact with Gaels and Picts?" in Ballin Smith et al (2007) p. 487

- 1 2 3 4 Hebridean Princess Scotland Retrieved on 17 October 2007

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 Lawson, Bill. "From The Outer Hebrides to Cape Breton - Part II". The Global Gazette. 10 September 1999. Retrieved on 14 October 2007

- ↑ History of Scotland The Highland Clearances Retrieved on 16 October 2007

- ↑ Island Fling, September, 2002. Vancouver Island Scottish Country Dance Society. Retrieved on 17 October 2007

- ↑ MacQuarrie, Brian. "In search of Scottish roots". Boston Globe Retrieved on 17 October 2007

- ↑ Turas Rannsachaidh dha 'n Albainn: Research Trip to Gaelic Scotland Retrieved on 16 October 2007

- ↑ Places in Cape Breton County, Nova Scotia Retrieved on 16 October 2007

References

- Ballin Smith, Beverley; Taylor, Simon; and Williams, Gareth (2007) West over Sea: Studies in Scandinavian Sea-Borne Expansion and Settlement Before 1300. Leiden. Brill. ISBN 978-90-04-15893-1

- Mac an Tàilleir, Iain (2003) Ainmean-àite/Placenames. (pdf) Pàrlamaid na h-Alba. Retrieved 26 August 2012.

External links

North Uist travel guide from Wikivoyage

North Uist travel guide from Wikivoyage- North Uist local community website

- Balranald Nature Reserve

- Taigh Chearsabhagh

- Explore North Uist

- Am Paipear Community Newspaper

Chisholm, Hugh, ed. (1911). "Uist, North and South". Encyclopædia Britannica (11th ed.). Cambridge University Press.

Chisholm, Hugh, ed. (1911). "Uist, North and South". Encyclopædia Britannica (11th ed.). Cambridge University Press.

Coordinates: 57°36′N 7°20′W / 57.600°N 7.333°W