Optic neuritis

| Optic neuritis | |

|---|---|

| Classification and external resources | |

| Specialty | Ophthalmology, neurology |

| ICD-10 | H46, G44.848 |

| ICD-9-CM | 377.30 |

| DiseasesDB | 9242 |

| MedlinePlus | 000741 |

| eMedicine | radio/488 |

| MeSH | D009902 |

Optic neuritis is a demyelinating inflammation of the optic nerve. It is also known as optic papillitis (when the head of the optic nerve is involved) and retrobulbar neuritis (when the posterior of the nerve is involved). It is most often associated with multiple sclerosis, and it may lead to complete or partial loss of vision in one or both eyes.

Partial, transient vision loss (lasting less than one hour) can be an indication of early onset multiple sclerosis. Other possible diagnoses include: diabetes mellitus, low phosphorus levels, or hyperkalaemia.

Signs and symptoms

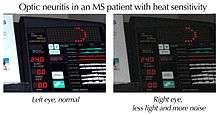

Major symptoms are sudden loss of vision (partial or complete), sudden blurred or "foggy" vision, and pain on movement of the affected eye. Early symptoms that require investigation include symptoms from Multiple Sclerosis (Twitching, No Coordination, Slurred Speech, Frequent episodes of Partial Vision Loss or blurred Vision), Episodes of "disturbed/blackened" rather than blurry indicate moderate stage and require immediate medical attention to prevent further loss of vision. Other early symptoms are reduced night vision, photophobia and red eyes. Many patients with optic neuritis may lose some of their color vision in the affected eye (especially red), with colors appearing subtly washed out compared to the other eye. Patients may also experience difficulties judging movement in depth which can be particular troublesome during driving or sport (Pulfrich effect). Likewise transient worsening of vision with increase of body temperature (Uhthoff's phenomenon) and glare disability are a frequent complaint. However, several case studies in children have demonstrated the absence of pain in more than half of cases (approximately 60%) in their pediatric study population, with the most common symptom reported simply as "blurriness." [1][2] Other remarkable differences between the presentation of adult optic neuritis as compared to pediatric cases include more often unilateral optic neuritis in adults, while children much predominantly present with bilateral involvement.

On medical examination the head of the optic nerve can easily be visualized by a slit lamp with high plus or by using direct ophthalmoscopy; however, frequently there is no abnormal appearance of the nerve head in optic neuritis (in cases of retrobulbar optic neuritis), though it may be swollen in some patients (anterior papillitis or more extensive optic neuritis). In many cases, only one eye is affected and patients may not be aware of the loss of color vision until they are asked to close or cover the healthy eye.

Etiology

The optic nerve comprises axons that emerge from the retina of the eye and carry visual information to the primary visual nuclei, most of which is relayed to the occipital cortex of the brain to be processed into vision. Inflammation of the optic nerve causes loss of vision, usually because of the swelling and destruction of the myelin sheath covering the optic nerve.

The most common etiology is multiple sclerosis or ischemic optic neuropathy (Blood Clot). Blood Clot[3] that supplies the optic nerve.[4] Up to 50% of patients with MS will develop an episode of optic neuritis, and 20-30% of the time optic neuritis is the presenting sign of MS. The presence of demyelinating white matter lesions on brain MRI at the time of presentation of optic neuritis is the strongest predictor for developing clinically definite MS. Almost half of the patients with optic neuritis have white matter lesions consistent with multiple sclerosis.

Some other common causes of optic neuritis include infection (e.g. Tooth Abscess in upper jaw, syphilis, Lyme disease, herpes zoster), autoimmune disorders (e.g. lupus, neurosarcoidosis, neuromyelitis optica), Pinch in Optic Nerve, Methanol poisoning, B12 deficiency and diabetes . Injury to the eye, which usually does not heal by itself.[5]

Less Common causes are: Papilledema, Brain tumor or abscess in occipitalregion, Cerebral trauma or hemorrhage,Meningitis Arachnoidal adhesions, sinus thrombosis, Liver Dysfunction or, Late Stage Kidney.

| Cause and Rank based on Deaths | Annual Num Cases TOTAL (US) (2011) | Annual Cases leading to Optic Neuritis | Percent | Prognosis and Treatment |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Multiple Sclerosis (Rank 33) | 400, 042 | 146,232 | 45% | Most Common cause, Almost all patients will experience some form of vision dysfunction. Partial vision loss can occur through the duration of the disease, Total vision loss occurs in severe cases and late stages |

| Blood Clot (Rank 29) (Optic ONLY) | 17,000 | 16,777 | 5% | Reversible if early and before reduced Blood flow causes permanent damage. |

| Nerve Pinch, (0) | NOT REPORTED | 4% | Usually heals itself, Treatment Not needed | |

| Injury to Optic Nerve (Including Poisoning, i.e. Methanol) (0) | 23,827 | 20,121 | <1% | Depends on Severity, Usually Treatable |

| Liver Dysfunction (Rank 19) If untreated can lead to Failure (Rank 8) | 141,211 | 11,982 | 7% | Poor Outcomes and Progresses and can lead to total vision loss |

| Reduced Kidney Function (Treatable with diet change) (Rank 67 - If untreated, can progress to Late Stage with much greater mortality rates. | 509,898 | 16,281 | 9% | Good Outcomes if Early, and can usually be treated with diet changes, Progresses and can lead to total vision loss |

| Late Stage Kidney Failure (Rank 7) | 33,212 | 1,112 | 2% | Poor Outcomes - Usually permanent nerve damage at this stage |

| Papilledema, (Brain tumor or abscess ) (Rank 10) | 45,888 | 9,231 | 3% | Depends on Severity |

| Meningitis (Rank 61) | 2,521 | 189 | <1% | Depends on Severity |

| Other Infections (Not from Abscess) | 5,561 | <1% | Good Outcomes, Treatable with Antibiotics or other Microbial drugs | |

| Diabetes (early Stage Treatable) Late Stage has worse prognosis (Rank 6) | 49,562 | 21,112 | 15% | Type 1 carries poor prognosis, Type 2 can be treated and vision returned |

| Unknown | n/a | 2% |

Demyelinating recurrent optic neuritis and non-demyelinating (CRION)

The repetition of an idiopathic optic neuritis is considered a distinct clinical condition, and when it shows demyelination, it has been found to be associated to anti-MOG and AQP4-negative neuromyelitis optica[7]

When an inflammatory recurrent optic neuritis is not demyelinating, it is called "Chronic relapsing inflammatory optic neuropathy" (CRION)[8]

When it is anti-MOG related, it is demyelinating and it is considered inside the anti-MOG associated inflammatory demyelinating diseases.

Treatment and prognosis

In the vast majority of MS associated optic neuritis, visual function spontaneously improves over the first 2–3 months, and there is evidence that corticosteroid treatment does not affect the long term outcome. However, for optic neuritis that is not MS associated (or atypical optic neuritis) the evidence is less clear and therefore the threshold for treatment with intravenous corticosteroids is lower. Intravenous corticosteroids have also been found to reduce the risk of developing MS in the following two years in those patients who have MRI lesions; but this effect disappears by the third year of follow up.[9]

Paradoxically it has been demonstrated that oral administration of corticosteroids in this situation may lead to more recurrent attacks than in non-treated patients (though oral steroids are generally prescribed after the intravenous course, to wean the patient off the medication). This effect of corticosteroids seems to be limited to optic neuritis and has not been observed in other diseases treated with corticosteroids.[10]

A Cochrane Systematic Review studied the effect of corticosteroids for treating participants suffering from optic neuritis.[11] Treatments reviewed included intravenous methylprednisone, oral methylprednisone, and oral prednisone. All treatments reviewed did not show any benefit in terms of recovery to visual acuity, contrast sensitivity, or visual field.[11]

The only case of Optic Neuritis being a vessel for another virus was in South Africa. Patient Master L Naicker had Optic Neuritis in 1998 and recovered quickly but he was later diagnosed with an extremely rare case of Viral Encephalitis. The virus was Herpes Simplex Type 1. The virus was cloaked by Optic Neuritis and soon entered the brain. Fortunately the above patient Master L Naicker recovered and is still the only case in history to have survived.

Epidemiology

Optic neuritis typically affects young adults ranging from 18–45 years of age, with a mean age of 30–35 years. There is a strong female predominance. The annual incidence is approximately 5/100,000, with a prevalence estimated to be 115/100,000.[12]

Society and culture

In the season five episode of Dr. Quinn, Medicine Woman, "Season of Miracles", Reverend Timothy Johnson is struck blind by optic neuritis on Christmas Day, 1872. He remains blind for the duration of the series. In Charles Dickens' "Bleak House" the main character, Esther Summerville suffers from a transient episode of visual loss with symptoms also observed during the course of optic neuritis.[13] Sir William Searle Holdsworth suggested "Bleak House" to have taken place in 1827.

See also

References

- ↑ Lucchinetti, C. F.; L. Kiers; A. O'Duffy; M. R. Gomez; S. Cross; J. A. Leavitt; P. O'Brien; M. Rodriguez (November 1997). "Risk factors for developing multiple sclerosis after childhood optic neuritis". Neurology. 59 (5): 1413–1418. doi:10.1212/WNL.49.5.1413. PMID 9371931.

- ↑ Lana-Peixoto, MA; Andrade, GC (June 2001). "The clinical profile of childhood optic neuritis". Arquivos de neuro-psiquiatria. 59 (2–B): 311–7. doi:10.1590/S0004-282X2001000300001. PMID 11460171.

- ↑ Rizzo JF, Lessell S (1991). "Optic neuritis and ischemic optic neuropathy. Overlapping clinical profiles". Arch. Ophthalmol. 109: 1668–72. doi:10.1001/archopht.1991.01080120052024. PMID 1841572.

- ↑ http://www.nejm.org/doi/full/10.1056/NEJMoa141296

- ↑ http://www.nature.com/eye/journal/v18/n11/full/6701575a.html

- ↑ http://smm.sagepub.com/content/early/2011/12/16/0962280211432067.abstract?rss=1

- ↑ Chalmoukou Konstantina; et al. (2015). "Recurrent Optic Neuritis (rON) is characterised by Anti-MOG Antibodies: A follow-up study". Neurology. 84 (14): 274.

- ↑ Kidd D.; Burton B.; Plant G. T.; Graham E. M. "Chronic relapsing inflammatory optic neuropathy (CRION)". Brain. 126: 276–284. doi:10.1093/brain/awg045.

- ↑ Beck RW, Cleary PA, Trobe JD, Kaufman DI, Kupersmith MJ, Paty DW, Brown CH (1993). "The effect of corticosteroids for acute optic neuritis on the subsequent development of multiple sclerosis. The Optic Neuritis Study Group". N. Engl. J. Med. 329 (24): 1764–9. doi:10.1056/NEJM199312093292403. PMID 8232485.

- ↑ Beck RW, Cleary PA, Anderson MM, Keltner JL, Shults WT, Kaufman DI, Buckley EG, Corbett JJ, Kupersmith MJ, Miller NR (1992). "A randomized, controlled trial of corticosteroids in the treatment of acute optic neuritis. The Optic Neuritis Study Group". N. Engl. J. Med. 326 (9): 581–8. doi:10.1056/NEJM199202273260901. PMID 1734247.

- 1 2 Vedula SS, Brodney Folse S, Gal RL, Beck R (2007). "Corticosteroids for treating optic neuritis". Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 1: CD001430. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD001430.pub2. PMID 17253459.

- ↑ Rodriguez M, Siva A, Cross SA, O'Brien PC, Kurland LT (1995). "Optic neuritis: a population-based study in Olmsted County, Minnesota". Neurology. 45 (2): 244–50. doi:10.1212/WNL.45.2.244. PMID 7854520.

- ↑ Petzold A (2013). "Optic Neuritis: Another Dickensian Diagnosis". Neuro-Ophthalmology. 37 (6): 247–250. doi:10.3109/01658107.2013.830313.