Pallache family

| Pallache | |

|---|---|

| Family name | |

|

Interior of Synagogue of El Transito | |

| Meaning | "Palace(s)" (English) |

| Region of origin | Iberian Peninsula |

| Related names | (de) "Palacio(s)" (Spanish ), (de) "Palacio(s)" (Portuguese ), "Palacci" (Italian ), etc., all ultimately from Collis Palatium |

| Clan affiliations | from 16th to 20th centuries in Morocco, Netherlands, Turkey, Egypt and then further diaspora |

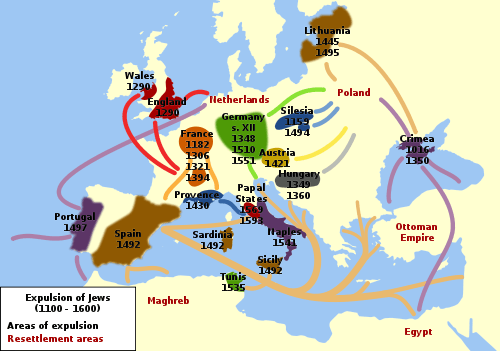

"Pallache" – also (de) Palacio(s), Palache, Palachi, Palacci, Palaggi, and many other variations (documented below) – is the surname of a prominent, Ladino-speaking, Sephardic Jewish family from the Iberian Peninsula, who spread mostly through the Mediterranean after the Alhambra Decree of March 31, 1492, and related events.

(This entry uses "Pallache" as an unifying name, based on scholarly preference, particularly three (3) entries for "Pallache" in Brill's Encyclopedia of Jews in the Islamic World[1][2][3] and the scholarly historical biography A Man of Three Worlds: Samuel Pallache, a Moroccan Jew in Catholic and Protestant Europe.[4])

The Pallache have had connections with both Portuguese and Spanish Sephardic communities, as detailed below.

The Pallache established themselves in cities in Portugal (?), Morocco, the Netherlands, Turkey, Egypt, and other countries from the 1500s through the 1900s. The family includes grand rabbis, rabbis, founders of synagogues and beth midrash, scientists, entrepreneurs, writers, and others. Best known to date are: Moroccan envoys and brothers Samuel Pallache (ca. 1550–1616) and Joseph Pallache, at least three grand rabbis of Izmir – Gaon[5] Haim Palachi (1788–1868), his son Abraham Palacci (1809–1899) and nephew Rahamim Nissim Palacci (1814–1907), at least one grand rabbi of Amsterdam, Isaac ben Judah Palache (1858-1927), linguist Juda Lion Palache (1886–1944), as well as American mineralogist Charles Palache (1869–1954).

History

Inquisitions and expulsions

In 1480, Queen Isabella I of Castile and King Ferdinand II of Aragon established a Tribunal of the Holy Office of the Inquisition (Spanish: Tribunal del Santo Oficio de la Inquisición), commonly known as the Spanish Inquisition (Inquisición española). Its dual purpose was to maintain Catholic orthodoxy in Spain while replacing the Medieval Inquisition under Papal control. On March 31, 1492, Isabella and Ferdinand issued the Alhambra Decree (or Edict of Expulsion), thereby ordering the expulsion of practicing Jews from the Kingdoms of Castile and Aragon, its territories, and it possessions by July 31 that year–in four months.[6] Jews who had converted to Christianity ("conversos") were safe from expulsion. Some 200,000 Jews converted; between 40,000 and 100,000 fled from the kingdom.[7] (On December 16, 1968, Spain revoked the Alhambra Edict.[8] On June 25, 2015, King Felipe VI of Spain announced Law Number 12/2015, which grants right of return to Sephardic Jews.[9][10][11] There are criticisms about shortcomings in the law.[12] By October 2016, Spain had processed more than 4,500 applicants, of which only three (3) had gained citizenship based on the actual law: the rest (number unstated) were naturalized by royal decree."[13])

On December 5, 1496, King ManueI of Portugal decreed that all Jews must convert to Catholicism or leave the country. Jews who converted to Christianity were known as New Christians. This initial edict of expulsion turned into an edict of forced conversion by 1497. In 1506, the Lisbon Massacre erupted. In 1535, Portugal launched its own inquisition. Portuguese Jews fled to the Ottoman Empire (notably Thessaloniki and Constantinople and to Morocco. Some went to Amsterdam, France, Brazil, Curaçao, and the Antilles. Some of the most famous descendants of Portuguese Jews who lived outside Portugal are the philosopher Baruch Spinoza (from Portuguese Bento de Espinosa), and the classical economist David Ricardo. While Portugal was under control of the Philippine Dynasty of the House of Habsburg (1581–1640), the Portuguese Inquisition blended with the Spanish.

The combined Spanish-Portuguese inquisitions caused one of the largest diasporas in Jewish history.

Iberia

(Research is currently underway to connect the Pallache more clearly back from Morocco to the Iberian Peninsula and probable ancestor, Samuel ben Meir Ha-Levi Abulafia / Samuel ha-Levi (ca. 1320–1360) of Cordoba, Andalusia, which would make the Pallache family a branch of the Abulafia family.)

According to Professor Mercedes García-Arenal,[14] the Pallaches were "a Sephardi family perhaps descended from the Bene Palyāj mentioned by the twelfth-century chronicler Abraham Ibn Da’ud as 'the greatest of the families of Córdoba'."[1]

According to Professor Giovanna Fiume,[15] "Verso i Paesi Bassi emigra anche la famiglia Pallache, forse dal Portogallo o dalla Spagna, oppure, secundo un'altra ipotesti, dalla nativa Spagna emigra a Fez." (translation: "The Pallache family also emigrated to the Netherlands, perhaps from Portugal or Spain, or, second, another hypothesizes, they emigrated [directly] from their native Spain to Fez.")[16]

According to Professor Reginald Aldworth Daly, the Pallaches were "persecuted Sephardim Jews of Portugal who were exiled to Holland."[17]

Portugal

At present, it is unclear as to whether members of the Pallache family went first to Portugal after Spain. However, new findings show that their intermarriage started earlier than supposed in A Man in Three Worlds (see "Netherlands," below).

Morocco

Jewish presence in Morocco goes back to Carthage, fared moderately, and often prospered under Muslim rule (e.g., the Marinid dynasty). From Morocco, they filtered into Al-Andalus (Islamic Spain, 711–1492) but began to return during the Spanish Reconquista, which mounted in the 10th Century. The Spanish-Portuguese expulsions and inquisitions sent floods of Jews back to Morocco on a larger scale. Resultant overcrowding in Moroccan cities led to tension, fires, and famines in Jewish quarters.

Moïse Al Palas (also Moses al-Palas[1]) (???–1535), born in Marrakesh, was a rabbi who moved to Tetuán and lived for a time in Salonica, then in the Ottoman empire. Before dying in Venice, he published Va-Yakhel Moshe (1597) and Ho'il Moshe (1597), and an autobiography.[1][18][19]

Isaac Pallache was a rabbi in Fez, Morocco, first mentioned in takkanot (Jewish community statutes) in 1588. His sons were Samuel Pallache (ca. 1550–1616) and Joseph Pallache. Isaac was married to a sister of Fez's grand rabbi, Judah Uziel; his nephew Isaac Uziel became a rabbi of the Neve Shalom community in Amsterdam.[4]

Netherlands

Jews began to settle in the Netherlands only at the end of the 16th Century. Thanks to its own recent (1581) independence from Spanish control, the Dutch Republic attracted Sephardic Jews in the Netherlands as a refuge from a common enemy, Spain.

After an unsuccessful attempt to return to Spain in the mid-1600s, Samuel and Joseph Pallache settled a new branch of the Pallache family in the Netherlands by 1608. There, they represented their benefactor, Zidan al-Nasir of Morocco, as well as the Dutch government, in complex negotiations with Morocco, the Netherlands, Spain, France, England, the Ottoman Empire, and other European states – often on behalf of more than one sponsoring state and (as stateless Jews) on their own behalf.[4]

The sons of both brothers continued in their fathers's footsteps, some remaining in the Netherlands (e.g., David Pallache), others returning to Morocco (e.g., Moses Pallache).

In the Netherlands, the surname solidified as "Palache" (a spelling variation which started in the 16th Century), and the family continues as Palache in the Netherlands to the present. In recent times, prominent members have included grand rabbi Isaac ben Judah Palache (1858-1927) and his son, Professor Juda Lion Palache (1887-1944).

A Man in Three Worlds did not find intermarriage between the Pallache brothers or sons and members of the Portuguese Sephardic community in the Netherlands. In fact, it documents the contrary, e.g., that sons Isaac and Joshuae did not go make such marriages. "It seems significant that no male member of the Pallache family ever married a woman from the Portuguese community... it is surely significant that neither Samuel nor any of his heirs were ever to marry into the great trading families of 'the Portuguese nation'."[4] In September 2016, however, two 1643 marriage certificates were discovered for David Pallache (1598–1650[20][21][22]) and Judith Lindo (???–October 30, 1665[23][24]) of Antwerp, daughter of Ester Lindo[25][26] Death details for David Pallache also confirm the marriage.[27] Further, three years later, in 1646, Samuel Pallache (1616–???), nephew of David, married Abigail (born 1622), sister of Judith Lindo.[28]

Turkey

Jewis have lived in Asia Minor (Turkey) since the 5th Century BCE. The Ottoman Empire welcomed Sephardic Jews expelled from the Iberian Peninsula. (Today, the majority of Turkish Jews live in Israel, while modern-day Turkey continues to host a modest Jewish population.)

The first reported Pallache in Turkey (then, the Ottoman Empire) dates to 1695, when Isaac Pallache of Leghorn (Livorno, Italy) wrote a letter to the Dutch consul in Smyrna (1695)[4][19] Currently, it is unknown whether the Pallache settled first in Istanbul or Izmir.

The Pallache appear in Izmir (then, "Smyrna") no later than the time of rabbi Jacob Pallache, who married the daughter of a previous grand rabbi Joseph Raphael ben Hayyim Hazzan.[29] Jacob's son became grand rabbi Haim Palachi (1788–1868), two of whose sons, Abraham (1809–1899) and Isaac aka Rahamim Nissim (1814–1907) also became grand rabbis there.

According to the Encyclopedia of Jews in the Islamic World:

The Pallache... produced several leading rabbinical scholars in the Ottoman city of Izmir (Smyrna) during the nineteenth and early twentieth centuries. Two of them, Hayyim ben Jacob and his sone Abraham, served as chief rabbi (hakham bashi) and became the focus of a fierce dispute that engulfed the town's Jewish community, while a third, Soloman ben Abraham, contributed to its decline.[2]

The Pallache continued in Turkey past the 1922 great fire of Smyrna; some left during Allied evacuation during World War II and died during the Holocaust (see below).[30]

Egypt

The Torah documents a long history of Jews in Egypt. Jews lived quietly under the Romans until the advent of Christianity (e.g., Emperor Heraclius I and Patriarch Cyrus of Alexandria). After the Arab conquest, Jews survived reasonably well under the Tulunids (863–905), the Fatimids (969–1169), and the Ayyubids (1174–1250) during whose rule Maimonides lived. Under the Bahri Mamluks (1250–1390), Jews began to feel less secure and less so under the Burji Mamluks (1390–1517). The Ottomans (1517–1922) took more active interest in the Jewish community and made substantial changes in their governance. Shabbatai Zvi visited Cairo, where his movement continued under Abraham Miguel Cardozo, physician to the pasha Kara Mohammed. Following the Damascus Affair, Moses Montefiore, Adolphe Crémieux, and Salomon Munk visited Egypt in 1840 and helped found schools with Rabbi Moses Joseph Algazi.

It was a period of rapid change in Egypt. As of 1867, the government began changing from pasha to khedive, to sultan and threw off Ottoman suzerainty. It also saw the building of the Suez Canal. Political unrest exploded after World War I, led by Saad Zaghlul and the Wafd Party) and culminating in the Egyptian revolution of 1919 and the issue by the UK government (colonial controllers in the 1800s) of a unilateral declaration of Egyptian independence on February 22, 1922.. (See History of Egypt under the British.) The new Egyptian government drafted and implemented a constitution in 1923 based on a parliamentary system. In 1924, Zaghlul became Prime Minister of Egypt. In 1936, Egypt concluded a new treaty with the UK. In 1952, the 1952 Revolution of the Free Officers Movement forced King Farouk to abdicate in support of his son Fuad, secured a British promise of withdrawal by 1954–1956, and led to the accession of Egypt's first modern president Gamal Abdel-Nasser.

No later than the close of the 19th Century, a branch of the Pallache family had settled in Egypt, with some remaining in Cairo into the 1950s.

Which members of the family had what foreign citizenship is as yet undetermined, e.g., Spanish under the Decree-Law of 29 December 1948 (Decreto-Ley de 29 de Deciembre de 1948) to extend Spanish protection for Sephardic Jews in Greece and Egypt:

DECRETO-LEY de 29 de diciembre de 1948 por el que se reconoce la condición de súbditos españoles en 1. extranjero a determinados sefardies protegidos de España: Por Canje de Notas efectuado por España con Egipto el dieciséis y diecisiete de enero de mil novecientos treinta y cinco, y con Grecia el siete de abril de mil novecientos treinta y seis, se convino que España continuarla otorgando su patrocinio y documentando, en consecuencia, a una serie de familias sefardies que, desde tiempos del imperIo ottoman, gozaban en aquellos territorios de tal gracia; y a dicho efecto, y como anejo a las referidas Notas, se establecireron unas listas, cuidadosamente seleccionadas, de esos beneficiarios, cuya futura condición de súbditos españoles se preveía en aquellas Notas...

(Legislative Decree of 29 December 1948 on the condition recognized Spanish subjects in certain Sephardim abroad 1. protected from Spain: Exchange of Notes effected by Spain with Egypt the sixteenth and seventeenth of January in 1935, and Greece on the seventh of April in 1936, it was agreed that Spain continue it by providing sponsorship and documenting, consequently, a number of Sephardic families from the Ottoman Empire times, enjoyed in the territories of such grace; and for this purpose, and as annexed to these notes, few, carefully selected lists of those beneficiaries, whose future status of Spanish subjects envisaged in those Notes were established...)[31]

(Neither "Palacci" nor variations on the surname appear in either the Egyptian or Greek lists.)

Palacci department store

In 1897, Palacci brothers Vita, Henri, and family established the "Palacci"[32] (Arabic Balaatshi) department store.[19][33] In 1904, the company's name was "Palacci Menasce et Fils",[34]). Shortly thereafter, it had become "Palacci Fils, Haim et Cie",[35] located on Muski street near the old Opera House.[33] By 1907, Vita Palacci had become head of the store.[36] Also in 1907, the Jewish Chronicle of London mentions "Mr. Vita Pallacci, the distinguished chief of the house of Palacci Pils, Halm and Co., which is well known inEurope and America."[37] By 1909, the Palacci had partnered with A. Hayam,[33] and the store employed 20 office clerks and more than 100–120 sales staff.[33][38] In 1910, "Albert Palacci & Co." appears as a Cairo firm interested in trading in silk.[39] At an unclear date, "Palacci, Menasce & Co." are recorded as having stores in Cairo, Tanta, and Mansoura.[40]

In 1916, "Palacci, Fils, Haym, and Co." were listed among "persons who have been granted licenses to trade in Egypt, with the British Empire, and with Allies of Great Britain."[41] The same year, "Palacci Fil, Haim & Co." filed a suit against "Mohamed Moh. Sélim."[42]

As community leaders, the Palacci supported Jewish causes inside and outside Egypt. In 1907, Vita Palacci was serving as president of la société de bienfaisence a "Hachemia":

En 1901, fut fondée au Caire une société de bienfaisance israélite dénommée "Hachemia." Cette institution qui est l'oeuvre exclusive des israélites de Turquie résidant en Egypte, prend de jour en jour un développement sensible. Pendant le dernier exercice, Hachemia a donne des soins médicaux à 1.000 malades furent visites à raison d'une piastre (0 fr. 25) par visite, sans compter les malades seignés à son compete dans divers hôpitaux du Caire et d'Alexandrie...

L'année dernière, le baron Edmond de Rothschild, lors de son dernier séjour au Cairo, fit a cette société un don de 3.000 fr. En 2901 Mme la baronne de Rothschild lue fil un don pareil.

Le comité directeur de la Hachemia est composé de personnalités marquantes de Caire. M. Vita Palacci, le distingué chef de l'importante maison du commerce Palacci fils, Haim et Cie, qui est bien connue en Egypte et au Soudain, en est le president actif et dévoué. Parmi ses collaborateurs, citons de Dr. Beneroya, le directeur du journal "La Vara"; M. Talvi, ingénieur au ministère des Travaux publies, etc.; Dr. Amster, médecin a l'administration des services sanitaire; et Dr. Isaac J. Levy d'Alexandrie, médecin de la communauté de l'hôpital Menascé, de la ligue contra la tuberculose et de la Municipalite de cette ville. Ces deux derniers étant membres honoraires théoriquement, actifs, pratiquement.

In 1901, a Jewish mutual aid society was founded in Cairo called the "Hachemia." This institution, which is a charitable organization for Turkish [Ottoman] Jews residing in Egypt, is making positive advances. Since the last fiscal year, Hachemia has provided medical care to a thousand visiting patients at the rate of one piaster (0.25 French francs) per visit, not including patients cared for and covered by Hachemia in several hospitals in Cairo and Alexandria...

Last year, Baron Edmond de Rothschild, during his last visit to Cairo, donated 3,000 francs. In 1901, Baroness de Rothschild made a gift in the same amount.

The committee leadership of Hachemia is composed of prominent people of Cairo. Mr. Vita Palacci, the distinguished head of the major commercial house Palacci Sons, Haim and Co., well known in Egypt and in Sudan, is the current and committed president of Hachemia. Among the other members of the leadership are: Dr. Beneroya, the editor of the newspaper "La Vara"; Mr. Talvi, an engineer at the Ministry of Public Works, etc.; Dr. Amster, doctor administering health services; and Dr. Isaac J. Levy of Alexandria, doctor at the Jewish Community Menascé Hospital, of Anti-Tuberculosis League, and the Alexandria Municipality. The latter two are honorary members theoretically, actively, and practically.[43]

During 1916–1917, "Palacci Fils, Haym & Co." was one of numerous donors in Egypt to the "Yeshibat Erez Israel (Rabbinical Institution) for the Refugee Rabbis from the Holy Land, established by the Alexandrian Rabbinate." From 1 Eyar 5676 through Sivan 5677 (4 April 1916 through to 29 June 1917), this group collected 120,427.5 PT (piasters), routed to its treasurer, E. Anzurat and published its third financial report. Donors were from Alexandria, Cairo, "suburbs," England, Australia, Canada, S. Africa, India, France, and the USA. The local collector in Cairo was Rabbi Haim Mendelof. The Palacci donated 500 PT, as did Maurice Calamari, I.M. Cattaui & Fils, Le Fils de M. Cicurel, Jaques & Elie Green.[44]

When Vita died in 1917, his oldest son Albert Vita Palacci succeeded as manager.[45][46] The store had offices overseas in Paris (1922) to purchase draperies and hardware, while its Cairo offices exported household essentials and perfumes.[47] By the mid-1920s, Palacci had branches on Fuad Street and in Heliopolis.[33]

In 1925, the Palacci partook in a "Gran Corso Carnivalesque" in Cairo, organized b the International Union of Commercial Establishment Employees of Cairo, along with 24 other grand department stores, including: Cicurel,[48] Bon Marché, Mawardi, Salamander, and Paul Favre. Other department stores of that time included: Chemla Fréres (see Jacqueline Kahanoff), Orosdi-Back, Sednaoui (see Elisa Sednaoui), Hannaux, Chalons, Ades (see Ades Synagogue and Yaakov Ades), Gattegno (see Caleb Gattegno and Joseph Gattegno), Madkur, Ahmad, Yusuf Gamal, Benzion (see owner Moïse Lévy de Benzion and Levi de Benzion), Morum's, Stein's, Raff's, Robert Hughes, Mayer, Tiring.[33] The history Maadi: 1904-1962 lists the following Jewish families around the Adly synagogu including: Rasson, Romano, Gold, Kabili, Rofe, Mizrahi, Chalem, Calderon, Agami, setton, Simhon, Sofeir. It also lists those Jewish families close by, including: Harris, Risolevi, Hettena, Sullam, Ades, Watoury, Palacci, Curiel, Basri, Farhi, Hazan, and Hazan.[49] The history Egypt: The Lost Homeland lists the following Jewish families in Cairo who "were considered Austrian and enjoyed the protection of the Austrian embassy, event though they were not Austrian citizens": Adda, Benarojo, Belilios, Cattaui, Forte, Goldstein, Heffez, Ismalun, Mondolfo, Pallaci, Picciotto, Rossano, and Romano.[50]

In 1933, the family of Mahmoud Abel Bak El Bitar had a lawsuit against "Pallaci, Haym & Co."[51] By 1935, the Palacci department store had experienced financial difficulties and then burned down; the family did not rebuild.[52][53] Nevertheless, the family company or derivatives continued. In 1947, an "H.M. Palacci & Co." appears as an agent of the G. R. Marshall & Co. exporting company of Richmond, Canada.[54]

The 1948 Cairo bombings, which included the Ades and Gattegno stores, did not deter the family; both Albert Vita Palacci and Dr. Victor Palacci appear in a 1955 Who's Who for Egypt,[55] while Henry Menahem Palacci in Cairo appears in the mid-1950s (along with an Albert Palacci in Belgium).[56] By the time Nasser had nationalized all Jewish-owned assets in Egypt (1958), most Palacci had left Cairo in diaspora–yet "Palacci Fils, Hayem et Cie." remained listed as a business in Cairo as late as 1959.[57]

Cairo residences

The Pallache family settled around the main home of Vita Palacci, a villa ("Palacci-Naggar-Ades Building") at No. 23 Ahmed Basha Street (Ahmad Pasha Street) in Garden City, Cairo.[58][59][60][61] Two of Vita Palacci's grandchildren, siblings Eddy and Colette, have written memoirs of their childhoods in Cairo (and Paris), which document Sephardic Jewish life in Cairo in the 1930s, including traditions, use of Ladino, and food recipes.[52][53] [59]

Alexandria

Pallache also settled in Alexandria. "Mordahai Palacci-Miram was likewise a Sephardi but from Constantinople, when he married Rosa Alterman, an Ashkenazi of German origin. Several of their children were born in Constantinople... but to escape an outbreak of plague came to Alexandria..." A "Ventura Palacci-Miram" is also mentioned.[62]

Congo venture: La Coupole

After World War I, participation of the Force Publique in the East African campaign resulted in a League of Nations mandate over the previously German colony of Ruanda-Urundi to Belgium as Belgian Congo (read more at "Belgian Congo").

In the mid-1940s, Henri Palacci, son of Menahem, son of Aaron (Henri) Palacci, founded "La Coupole" store in Kinshasa, Democratic Republic of the Congo (then Leopoldville, Belgian Congo), as documented in

Les commerçants juifs ont contribué à l'émancipation des "indigènes," en les initiant aux produits manufacturés. Ainsi, les boutiques "Au Chic" du Groupe Hasson et "La Coupole" d’Henri Palacci, ouverts, à Léopoldville, vers 1946, vendent à tous et refusent toute forme de discrimination raciale. Leurs rapports quotidiens avec les colonisés distinguaient les Juifs des autres Blancs. Et lors des évènements tragiques de 1960, aucun Juif ne fut molesté par la foule en colère.

Jewish merchants contributed to the empowerment of "indigenous" people by introducing them to manufactured goods. The shops "Au Chic" (Hasson Group) and "La Coupole" (Henry Palacci), opened in Leopoldville, around 1946, selling to all and refusing any form of racial discrimination. Daily contact with colonized Jews differed from other Whites. And during the tragic events of 1960, no Jew was molested by mobs.

(See "Congo Crisis" for more on the emergence of the DR Congo.[63])

Other countries

The Pallache had established themselves in Jamaica by the 19th Century in the sugar trade. In 1825, the London Gazette posted notice of a partnership that included Mordecai Palache and Alexander Palache "of Kingston, in the Island of Jamaica."[64] A "Charles, son of Mordechai Palache" is recorded in 1847.[65] Numerous people named Palache continued to appear.[66] Most prominent among them was the Honorable John Thomson Palache ("a coloured solicitor"[67]).[68][69][70]

A "Vita Palacci" appears in Argentina by 1855.[71]

21st Century

Continued expulsions and diaspora have dispersed the Pallache family to many countries in the Americas, Europe, and farther afield.

By the 20th Century, the Pallache had established and the United States. The family of noted American mineralogist Charles Palache (1869–1954) came to California from Jamaica.[17][72] Numerous Palacci came to the States in diaspora from Turkey and Egypt, including Colette (Palacci) Rossant.

Synagogues

Netherlands

Samuel Pallache may have helped found the first synagogue in Amsterdam.[19][73] As early as his 1769 Memorias do Estabelecimento e Progresso dos Judeos Portuguezes e Espanhoes nesta Famosa Cidade de Amsterdam, David Franco Mendes records a first minyan in Amsterdam with sixteen worshippers, including Samuel and Joseph Pallache.[74][75] Other sources go further to claim that this first minyan occurred in Palache's home, as they were dignitaries (envoys from Morocco)[76][77] and occurred around 1590[78] or Yom Kippur 1596.[79][80] However, in their book A Man of Three Worlds' on Samuel Pallache, Professors García-Arenal and Gerard A. Wiegers[81] point out that the Pallache brothers arrived in Amsterdam in the first decade of the following century.[4]

Turkey

Around 1840, the Pallache home in Smyrna became today's Beth Hillel Synagogue (Turkish Bet-Ilel Sinagogu) and seat of a yeshiva or beit madras. The synagogue lies in the Kemeraltı marketplace district in Izmir and is named after Haim or Abraham Palacci. Professor Stanford J. Shaw stated it was Haim who founded the Beth Hillel Palacci.[82] or his son Abraham. According to Jewish Izmir Heritage, "In the 19th century, Rabbi Avraham Palache founded in his home a synagogue named Beit Hillel, after the philanthropist from Bucharest who supported the publication of Rabbi Palache's books. However, the name 'Avraham Palache Synagogue' was also used by the community."[83] This synagogue forms a cluster of eight extant (from a recorded peak of 34 in the 19th Century), all adjacent... [making] Izmir is the only city in the world in which an unusual cluster of synagogues bearing a typical medieval Spanish architectural style is preserved ...[and] creating an historical architectural complex unique in the world."[84] The Zalman Shazar Center also refers to Beit Hillel synagogue as "Avraham Palaggi's synagogue" but then states that "the synagogue was founded by Palaggi Family in 1840" and that Rav Avraham Palaggi "used" it. "The building had been used as a synagogue and a Beit Midrash. The synagogue has not been used since 1960's." It concludes, "The synagogue was founded by the Palaggi family and is therefore very important."[85]

Egypt

The Palaccis were one of many families that helped maintain the Sephardic Sha'ar Hashamayim Synagogue (Cairo) on Adly Street in downtown Cairo.[86]

Yeshivas

Turkey

Journey into Jewish Heritage states that Palacci founded the Beit Hillel Yeshiva in Izmir in the middle of the 19th century.[87] Current sources are unclear, but it is likely the same as the Beit Midrash mentioned above.[85]

Israel

A seminary was named in Palachi's honor in Bnei Brak, Israel.[2]

Writings

- Haim Palachi – of 82 publications, 36 (as of September 2016) are listed under: Haim Palachi

- Many other rabbinical works by other Palache rabbis, including: Abraham Palacci, Rahamim Nissim Palacci, and Joseph Palacci

- Colette (Palacci) Rossant: Apricots on the Nile (1999, 2004)[59]

- Eddy Palacci: Des étoiles par cœur (2012)[52]

Documented spellings of surname

As the Pallache settled in new cities with new languages, spellings of the surname changed. Oftentimes, changes occurred via officialdom. In the 19th Century, for example, American officials at Ellis Island would shorten, simplify, or change altogether the spellings of foreigners upon arrival. In the 20th Century, Turkish officials forced all nationals to adopt surnames under the 1934 Surname Law.

Variations on the Pallache name appear on both Spanish and Portuguese lists of Sephardic names. For instance, "Palacci" is listed as Spanish Sephardic,[88] while "Pallache" is listed as Portuguese Sephardic.[89]

Samuel Pallache's name appeared in several forms–including variations that he himself used.[90] A German Vierteljarhschrift mentions both "Duarte de Palacios" and "Duarte Palache" when referring to the same person, thus making direct equation between the names "de Palacios" and "Palache."[91]

Documented names include:

- Pallache'[1][2][3][4][19]

- Palache[2][3][29][92] (e.g., Samuel Pallache's death certificate[93]) (as Portuguese[94])

- Palacio[1][19]

- de Palacios and Palacios[1][73][95][96][97][98] ("Clara Palacios, dochter van J[aco]b de Palacios... een dochter van Jacob de Palacios"[99])

- Palacio[4]

- Palatio[4]

- Palachio[4]

- Palazzo."[4]

- de Palatio[18][19]

- al-Palas[1][18]

- Pallas[18][19]

- Palaggi[1][2][3][18][19][100] (as Portuguese[94])

- Balyash[18][19]

- Palacci[2][19][101][102][103][104][105][106][107]

- Palate,[108][109]

- Palatie,[108]

- Paliache[110]

- Palachi as in "Haim Palachi" or "Hayim Palachi"[111]

- Paligi[109]

- Palagi (for Haim Palachi as "Chaim Palagi)[112][113][114]

- Palatchi (in Turkey)[30][115][116]

- Bene Palyāj (mentioned by the twelfth-century chronicler Abraham Ibn Da’ud as "the greatest of the families of Córdoba"[1]

- Palyaji[19]

- Ibn Falija[19]

- Falaji[117]

- Palaji[118]

- Faleseu (Semuel Palache, buried July 4, 1717)[119][120]

- Palachy[121]

- Palaci[122]

Family tree

The approach that the outline below follows is: 1) use Moïse Rahmani's essay "Les Patronymes: une histoire de nom ou histoire tout court" as a base, 2) add findings from the penultimate chapter of García-Arenal and Wiegers's A Man of Three Worlds: Samuel Pallache, a Moroccan Jew in Catholic and Protestant Europe (1999, 2007), and 3) add further information – all with citations. The index developed for Abraham Galante's Jews of Turkey is another major source for the Izmir branch of the family.

16th-17th Centuries Morocco and Netherlands

Pallache of the 16th-17th Centuries, who originated from Morocco include:

- Moïse Al Palas (???–1535), born in Marrakesh, lived in Salonica, died in Venice[18][19]

- Isaac Pallache(???–1560[19]), rabbi of Fez (mentioned 1588)[110]

- Isaac Uziel (???-1622), nephew of Isaac Palacche, rabbi of Amsterdam's second Separhdic synagogue "Neve Shalom"

- Samuel Pallache (ca. 1550-1616), envoy and dragoman of Morocco (1608-1616)[19][110]

- Joseph Pallache (ca.1552-1638/1639/1649), envoy and dragoman of Morocco (1616-1638)[19][110][123][124]

- Isaac Palache, envoy of Morocco to the Ottoman Sultan, later broker in Amsterdam, later served sultan of Morroc (1647)[4][110]

- Yehoshua Pallache (Joshua), co-envoy of Morocco to Poland (1618-1619), tax collector of Salé, Morocco[110]

- Samuel Pallache (1616/1618–???), represented his uncle Moses's request to marry levitically the wife of his other uncle David[110]

- Manasseh ben Samuel (or Menasseh Ben Israel?), helped gain return of Jews to England from Oliver Cromwell (1656, following their expulsion in 1290)[19]

- Samuel Pallache (1616/1618–???), represented his uncle Moses's request to marry levitically the wife of his other uncle David[110]

- David Pallache (1598–1650?), envoy of Morocco to King Louis XIII of France (1631–1632), envoy and dragoman of Morocco (1638-1648/1649), and business partner of Michael de Spinoza (father of Baruch Spinoza)[27][110][125][126]

- Moses Pallache(???–1650[19]), advisor to four sultans of Morocco (1618 to 1650): Muley Zaydan (1603–1627), Muley Abd al-Malik (1623–1627), Muley al-Walid (1631–1636), and Muley Muhammad al-Shakh al-Saghir (1636–1655)[110]

- Abraham Palacci, 17th Century merchant (French négocient) to Safi, Morocco[110]

17th-20th Centuries Netherlands

Pallache (as "Palache") of the 17th-20th Centuries in the Netherlands include:

- Judah Pallache

17th-20th Centuries Ottoman empire

Pallache of the 17th-20th Centuries in Smyrna / Izmir, Turkey (then Ottoman Empire) include:

- Isaac Pallache of Leghorn (Livorno, Italy) and later Izmir, where he wrote letter to Dutch consul in Smyrna requesting projection for "Salomón Moses" (1695)[4][19][110]

- Samuel Palacci, died 1732, "among the most ancient graves in Kuşadası cemetery"[129]

[...]

- Jacob Pallache (ca. 1755-1828), 18th Century rabbi

- Isaac Palacci, brother of Haim[129]

- Salomon Palache[110]

- Hayyim Pallache (Palagi) (1788-1869), hakham bachi (1858), grand rabbi and kabbalist,[19][110] member of Communal Council in Istanbul, died February 9, 1869[129]

- Abraham Palacci (1809-1899), grand rabbi,[19][110] funded for Beit Hilel yeshiva 1840, chief rabbi 1869, died 1899[129]

- Isaac Palacci, son of Haim[129] AKA Rahamim Nissim Palacci (1813–1907), grand rabbi after Haim and Abraham and author of Avot harosh at Isaac Samuel Segura printing house Izmir 1869[129]

- Joseph Palacci (1819–1896), , rabbi and author of "Voyoseph Abraham Dito Libro en Ladino for las Ma'alot de Joseph ha-Zaddig" (1881),[110] printed book Yosef et ehav at Mordekhai Isaac Barki printinghouse in Izmir 1896[129]

[...]

- Benjamin Palacci 1890, later rabbi in Tire (a district of Izmir)[129]

- Hilel Palacci, member of Izmir communal council 1929–1933[129]

- Jacob Palacci, director of choir Choeur des Maftirim in Istanbul 19th-20th century[129]

- Nissim Palacci, helped Jewish Hospital Istanbul early 20th Century, member of Galata community committee 1928–1931, member Haskeuy community committee 1935–1939[129]

19th-20th Centuries Egypt

Other Pallache who left Turkey (Izmir or Istanbul) for Egypt include:

- Vita Palacci (ca. 1865–1917[45]), left Izmir for Cairo, co-founded Palacci department store (first "Palacci Menasce et Fils",[34]) then "Palacci Fils, Haim et Clie[35]) (1897"[33])

- Isaac Palacci (1893-1940), Paris-based négocient for Palacci department store[52][59]

- Eddy Palacci (1931–2016)[52][59]

- Colette (Palacci) Rossant (living)[52][59]

- Juliette Rossant (living)[59]

- Isaac Palacci (1893-1940), Paris-based négocient for Palacci department store[52][59]

- Henri Palacci, brother of Vita, left Izmir for Cairo, traded in chemical products in Egypt and Sudan[19]

- Menahem Palacci, (co-)founded Palacci department store in Cairo, classmate of King Fouad I of Egypt, helped Jews in Egypt become Egyptian citizens (1922)[19]

17th-20th Centuries elsewhere

Other Pallache of the 17th-20th Centuries in other lands and who are (to date) unclearly connected to Dutch or Turkish/Egyptian branches include:

- Jacob Pallache, 17th Century rabbi of Marrakesh and later Egypt, supporter of Sabbatai Tsevi (1626–1676)[4]

- Abraham Pallache, 18th Century rabbi of Safed, Israel (then Ottoman empire)[110]

- Abraham Pallache, 19th Century rabbi of Tétouan, Morocco, and author in 1837[110]

- Samuel Pallache, 18th Century rabbi in the Netherlands (author of Sheroot Be Ekhol u Bet Mishtek, published 1770)[110]

- Moshe Samuel Palache (???-1859), rabbi in Jerusalem (son of Samuel Pallache above?)[110]

- Palache of Jamaica[110][132]

- Charles Palache (1869–1954)

Holocaust victims

- Henri Palacci/Palatchi (March 26, 1898–???), deported from Istanbul to France (1942)[30] – seem to match details for Henriette Palatchi (1898–1943), died in Holocaust[133]

- Isaac Palacci/Palatchi (April 15, 1900–???), deported from Istanbul to France (1942)[30] – seems to match details for Henry Palatchi (1900–1944) died in Holocaust[134]

- Mordecai Palatchi/Palacci (1903–???), deported from Bursa to France (1942)[30] – seems to match details for Mordehai Palatchi (1903–1942), died in Holocaust.[135]

See also

- Pallache (surname)

- Samuel Pallache

- Joseph Pallache

- Moses Pallache

- David Pallache

- Isaac Pallache

- Haim Palachi

- Abraham Palacci

- Rahamim Nissim Palacci

- Joseph Palacci

- Juda Lion Palache

- Charles Palache

- Colette (Palacci) Rossant

- Juliette Rossant

- Gabriel Palatchi

- Ladino

- Kemeraltı: Synagogues

- Sephardi Jews

- History of the Jews in Spain

- History of the Jews in Portugal

- Expulsion of the Jews from Spain

- Expulsion of Jews and Muslims from Portugal

- History of the Jews in Morocco

- History of the Jews in the Netherlands

- History of the Jews in Turkey

- History of the Jews in Egypt

- History of the Jews in Jamaica

- History of the Jews in England

- History of the Jews in Latin America and the Caribbean

- List of synagogues in Turkey

- List of Caribbean Jews

- Moïse Lévy de Benzion

- Cicurel family

- Moïse Rahmani

References

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 García-Arenal, Mercedes (2010), "Pallache Family (Moroccan Branch)", in Stillman, Norman A., Encyclopedia of Jews in the Islamic World, 4, Brill

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 Lewental, D Gershon (2010), "Pallache Family (Turkish Branch)", in Stillman, Norman A., Encyclopedia of Jews in the Islamic World, 4, Brill

- 1 2 3 4 Ben Naeh, Yaron (2010), "Pallache, Ḥayyim", in Stillman, Norman A., Encyclopedia of Jews in the Islamic World, 4, Brill, pp. 38–39

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 García-Arenal, Mercedes; Wiegers, Gerard (2007). A Man of Three Worlds: Samuel Pallache, a Moroccan Jew in Catholic and Protestant Europe. Johns Hopkins University Press. pp. 12 (background, surname), 101–127 (descendants).

- ↑ Wallach, Shalom Meir (1996). Ben Ish Chai Haggadah. Feldheim Publishers. pp. 11 ("And the Lion of the gaonim, the elderly Gaon Chaim Palaji of Izmir").

- ↑ "Edict of the Expulsion of the Jews (1492)". Foundation for the Advancement of Sephardic Studies and Culture. Retrieved 16 September 2016.

- ↑ Pérez, Joseph. History of a Tragedy. p. 17.

- ↑ Eders, Richard (17 December 1968). "1492 Ban on Jews Is Voided by Spain". New York Times.

- ↑ "Dispositions Generales: Jefature del Estado: Ley 12/2015, de 24 de junior en material de concession de la nacionalidad española a los sefardíes originarios de España" (PDF). Boletín Official del Estado. 25 June 2015. Retrieved 16 September 2016.

- ↑ "Platform for the request of Sephardic origin certificates". Federación de Comunidades Judías de España. Retrieved 16 September 2016.

- ↑ "Bill Granting the Spanish Citizenship to Sephardic Jews with Spanish Origins" (PDF). Ministerio de Asuntos Exteriores y Cooperación = Portal gestionado por la Oficina de Información Diplomática. 11 June 2015. Retrieved 15 October 2016.

- ↑ Akman, Dogan (October 2016). "Spain's correction of her "Historical Mistake and Injustice": Spanish citizenship for the 'sefardies': An assessment". Sephardic Horizons. Retrieved 24 October 2016.

- ↑ Zara, Yoram (18 October 2016). [Spain, Portugal naturalize nearly 5,000 Sephardic Jews "Spain's correction of her "Historical Mistake and Injustice": Spanish citizenship for the 'sefardies': An assessment"] Check

|url=value (help). Portuguese Citizenship Sephardic. Retrieved 24 October 2016. - ↑ "Mercedes García-Arenal Rodríguez". Centro de Ciencias Humanas y Sociales. Retrieved 13 September 2016.

- ↑ "Giovanna Fiume". University of Palermo. Retrieved 13 September 2016.

- ↑ Fiume, Giovanna (2012). Schiavitù mediterranee. Corsari, rinnegati e santi di età moderna. Milan: Bruno Mondadori. Retrieved 4 September 2016.

- 1 2 Daly, Reginald A. (1957). "Charles Palache, 1869—1954: A Biographical Memoir" (PDF). Washington: National Academy of Sciences. Retrieved 16 September 2016.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 "Palache". Jewish Virtual Library. Retrieved 1 September 2016.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 19 20 21 22 23 24 25 26 Rahmani, Moïse (December 1990). "Les Patronymes: une histoire de nom ou histoire tout court" [A Story of a Name or a Short History] (PDF). Los Muestros (in French). Sefard (Institut Sephardi Europeen): 32. Retrieved 11 September 2016.

- ↑ "Amsterdam - Burials of the Portuguese Israelite Congregation - Palache, David". Dutch Jewry. Retrieved 20 October 2016.

- ↑ "Amsterdam - Burials of the Portuguese Israelite Congregation - Archive # 19178 Palache, David". Dutch Jewry. Retrieved 20 October 2016.

- ↑ "Amsterdam - Burials of the Portuguese Israelite Congregation - Image Palache, David". Dutch Jewry. Retrieved 20 October 2016.

- ↑ "Amsterdam - Burials of the Portuguese Israelite Congregation - Palache, Judith Linda". Dutch Jewry. Retrieved 20 October 2016.

- ↑ "Amsterdam - Burials of the Portuguese Israelite Congregation - Archive # 19226 Palache, Judith Linda". Dutch Jewry. Retrieved 20 October 2016.

- ↑ "Amsterdam - Traditional Sephardic marriages - David Palache and Judith Lindo". Dutch Jewry. Retrieved 8 September 2016.

- ↑ "Amsterdam - Traditional Sephardic marriages - David Palache and Judith Lindo". Dutch Jewry. Retrieved 8 September 2016.

- 1 2 "Begraafplaats Ouderkerk a/d Amstel - Palache, David". Dutch Jewry. Retrieved 8 September 2016.

- ↑ "Amsterdam - Traditional Sephardic marriages - Samuel Palache and Abigael Lindo". Dutch Jewry. Retrieved 8 September 2016.

- 1 2 Hazan, G. Ender (2015). Hazan Genealogy: "Aaron De Yoseph Hazan - Izmir Jews 1600-2000. Lulu. p. 32. Retrieved 13 September 2016.

- 1 2 3 4 5 Klarsfeld, S. (1978). "Mémorial de la Déportation des Juifs de France 1942-1945" (PDF). Paris. Retrieved 12 September 2016.

- ↑ "Decreto-Ley de 29 de Deciembre de 1948" (PDF). Ministerio de la Presidencia del Gobierno de España: Agencia Estatal Boletín Oficial del Estado (BOE). 19 January 1949. Retrieved 16 October 2016.

- ↑ Gutkowski, Hèléne (1999). Erase una vez... Sefarad. Lumen. p. 394. Retrieved 20 September 2016.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 Reynolds, Nancy (2012). A City Consumed: Urban Commerce, the Cairo Fire, and the Politics of Decolonization in Egypt. Stanford University Press. pp. 53–55 (prominence, competitors), 61–62 (founding, Hayam, size), 224. Retrieved 29 August 2016.

- 1 2 Japan Weekly Mail. Yokohama: (unknown). 1904. pp. 359). Retrieved 29 August 2016.

- 1 2 Special Consular Reports. U.S. Government Printing Office. 1915. pp. 180). Retrieved 29 August 2016.

- ↑ Archives israélites, Volume 68. Bureau des Archives Israelites. 1907. p. 380. Retrieved 29 August 2016.

- ↑ "November 15 1907 archive". The Jewish Chronicle. 15 November 1907. pp. 10–11. Retrieved 26 October 2016.

- ↑ Atabaki, Touraj; Brockett, Gavin (2009). Ottoman and Republican Turkish Labour History. Cambridge University Press. p. 98. Retrieved 16 September 2016.

- ↑ "Egypt a Promising Market for Silk Goods". Silk, Volume 4. 1910: 36. Retrieved 20 September 2016.

- ↑ Le Brun, Annie (1994). 20,000 lieues sous les mots, Raymond Roussel. Jean-Jacques Pauvert. p. 188. Retrieved 20 September 2016.

- ↑ Great Britain and the East, Volume 12. 1916. p. 214. Retrieved 20 September 2016.

- ↑ Lebsohn, Théodore; Palagi, Dario; Rensis, A.; Schiarabati, A.; Grandmoulin, J. (1916). Bulletin de législation et du jurisprudence égyptiennes. V. Penasson. pp. xv. Retrieved 20 September 2016.

- ↑ Galante, Abraham (27 October 1907). "Correspondance Pariculiere des 'Archives'". Paris: Archives Israelites: Recoil Politique et Religieux (Volume 68). p. 380. Retrieved 26 October 2016.

- ↑ "Financial Report No. 3" (PDF). Yeshibat Erez Israel (Rabbinical Institution) for the Refugee Rabbis from the Holy Land. 1917. pp. 6–12 (Alexandra), XX (Cairo), 23 (Palacci). Retrieved 26 October 2016.

- 1 2 Gazette des tribunaux mixtes d'Egypte: revue judiciaire mensuelle, Issues 7-8. Impr. A. Procaccia. 1917. p. 183. Retrieved 29 August 2016.

- ↑ Gazette des Tribunaux mixtes d'Égypte, Volume 7. Molco, Petrini & Company. 1917. p. 183. Retrieved 29 August 2016.

- ↑ International Trade Developer: Propagador de Comercio Internacional. International trade Developer. 1922. pp. 90 (Paris), 108 (Paris), 111–113 (Cairo), 147 (Cairo). Retrieved 29 August 2016.

- ↑ Beinin, Joel (1998). The Dispersion of Egyptian Jewry: Culture, Politics, and the Formation of a Modern Diaspora. Los Angeles: University of California Press. p. 44. ISBN 0-520-21175-8.

- ↑ Raafat, Samir (1994). Maadi 1904-1962: Society and History in a Cairo Suburb. Palm Press. pp. 104, 277, 278. Retrieved 20 September 2016.

- ↑ Douer, Alisa (2015). Egypt - The Lost Homeland: Exodus from Egypt, 1947-1967: The History of the Jews in Egypt, 1540 BCE to 1967 CE. Berlin: Logos Verlag. pp. 290 (fn 744). Retrieved 20 September 2016.

- ↑ Lebsohn, Théodore; Palagi, Dario; Rensis, A.; Schiarabati, A.; Grandmoulin, J. (1933). Bulletin de législation et de jurisprudence égyptiennes, Volumes 45-46. pp. xvii. Retrieved 20 September 2016.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 Palacci, Eddy (2012). Des étoiles par cœur. Elzevir. pp. 13–14 (difficulties). Retrieved 13 September 2016.

- 1 2 Dammond, Liliane S. (2011). The Lost World of the Egyptian Jews: First-person Accounts from Egypt's Jewish Community in the Twentieth Century. iUniverse. pp. 210 (department store), 211 (Garden City), 215 (store burns). Retrieved 16 September 2016.

- ↑ Machinery Lloyd, Volume 19, Issue 2. Continental and Overseas Organisation Limited. 1947. p. 132. Retrieved 16 September 2016.

- ↑ Blattner, James Elwyn (1955). Who's who in U.A.R and the Near East. Paul Barbey Press. p. 555. Retrieved 16 September 2016.

- ↑ Sanua, Victor D. (2005). Egyptian Jewry: guide to Egyptian Jewry in the mid-fifties of the 20th century : the beginnings of the demise of a vibrant Egyptian Jewish community. International Association of Jews from Egypt. p. 109 (Albert Palacci), 127 (Henry Palacci, son of Menahem). Retrieved 16 September 2016.

- ↑ Marconi's International Register. Telegraphic Cable & Radio Registrations. 1959. p. 992. Retrieved 16 September 2016.

- ↑ Rossant, Colette (1999). Memories of a Lost Egypt. Clarkson Potter. pp. 2–3 (photo of Vita Palacci), 19 (Palacci agencies), 30 (Garden City villa), 33 (Ladino) 48–51 (recipes – all over book), 70–76 (marriages). Retrieved 13 September 2016.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 Rossant, Colette (2004). Apricots on the Nile: A Memoir with Recipes. Atria. pp. 2–3 (photo of Vita Palacci), 19 (Palacci agencies), 30 (Garden City villa), 33 (Ladino) 48–51 (recipes – all over book), 70–76 (marriages). Retrieved 13 September 2016.

- ↑ Raafat, Samir (6 August 1998). "Garden City: A Retrospective, Part I". Retrieved 29 August 2016.

- ↑ Raafat, Samir (6 August 1998). "Garden City: A Retrospective, Part 5". Retrieved 19 September 2016.

- ↑ Haag, Michael (2004). Alexandria: City of Memory. Yale University Press. p. 232 (Mordahai Palacci-Miram), 347 (Ventura Palacci-Miram). Retrieved 16 September 2016.

- ↑ Rahmani, Moïse (February–May 2010). "La présence juive au Congo, depuis un siècle" [A Century of Jewish Presence in Congo] (PDF). Kadima No. 016 (in French). Kinshasa: Communauté Israélite de Kinshasa: 15–21. Retrieved 20 September 2016.

- ↑ Neuman, T. (1825). The London Gazette, Part 2. p. 1204. Retrieved 13 September 2016.

- ↑ Yoffe, Oron (1997). The Jews of Jamaica: tombstone inscriptions, 1663-1880. Ben Zvi Institute. pp. 73, 165, 169. Retrieved 13 September 2016.

- ↑ Eyre, Edward John (1866). Jamaica: Addresses to His Excellency Edward John Eyre, Esquire, &c., &c., 1865, 1866. Jamaica: M. DeCordova. Retrieved 13 September 2016.

- ↑ Monteith, Kathleen E. A.; Richards, Glen (2001). Jamaica in Slavery and Freedom: History, Heritage and Culture. University of the West Indies Press. p. 356. Retrieved 13 September 2016.

- ↑ Bryan, Patrick E. (2000). The Jamaican People, 1880-1902: Race, Class, and Social Control. University of the West Indies Press. Retrieved 13 September 2016.

- ↑ The Handbook of Jamaica. 1906. Retrieved 13 September 2016.

- ↑ The Handbook of Jamaica. 1908. Retrieved 13 September 2016.

- ↑ Revisit Del Río de La Plata, Issues 1831–1855. Argentina. 1917. p. 24. Retrieved 16 September 2016.

- ↑ "Palache family. Papers of the Palache family, 1839-2006 (inclusive), 1895-1988 (bulk)". Harvard University. March 2006. Retrieved 16 September 2016.

- 1 2 "The Palache Family from Almeria and Cordova, Spain & Fez, Morocco c.1510". Tzora Folk. Retrieved 13 September 2016.

- ↑ Henriques Castro, David (1875). 1675-1875: De synagoge der Portugeesch-Israelietische gemeente te Amsterdam. Belinfante. p. 5. Retrieved 1 September 2016.

- ↑ Brasz, Chaya; Kaplan, Yosef, eds. (2001). Dutch Jews As Perceived by Themselves and by Others: Proceedings of the Eighth International Symposium on the History of the Jews in the Netherlands. Brill. p. 67.

- ↑ Kurlansky, Mark (2008). A Chosen Few: The Resurrection of European Jewry. New York: Random House. p. 82. Retrieved 31 August 2016.

- ↑ Skolnik, Frank; Berenbaum, Michael, eds. (2007). Encyclopaedia Judaica, Volume 15. Macmillan Reference. p. 573.

- ↑ Kritzler, Edward (2009). "Jewish Pirates of the Caribbean". Penguin Random House. pp. 10 (background), 75–92 (chapter). Retrieved 1 September 2016.

- ↑ Henriques Castro, David (1999). Keur van grafstenen op de Portugees-Isräelietische begraafplaats te Ouderkerk aan de Amstel met beschrijving en biografische aantekeningen: met platen. Stichting tot Instandhouding en Onderhoud van Historische Joodse Begraafplaatsen in Nederland. pp. 36 (first minyan), 91–93. Retrieved 1 September 2016.

- ↑ Fendel, Zechariah (2001). Lights of the Exile. Hashkafah Publications. pp. 45–46. Retrieved 1 September 2016.

- ↑ "dhr. prof. dr. G.A. (Gerard) Wiegers". University of Amsterdam. Retrieved 13 September 2016.

- ↑ Shaw, Stanford J. The Jews of the Ottoman Empire and the Turkish Republic. p. 67 (synagogue), 170, 173–175 (dispute), 180, 183.

- ↑ "Beth Hillel Synagogue". Izmir Jewish Heritage. Retrieved 2 September 2016.

- ↑ "Synagogues". Izmir Jewish Heritage. Retrieved 2 September 2016.

- 1 2 "Index Card #7 BEIT HILLEL" (PDF). Journey into Jewish Heritage - Zalman Shazar Center. Retrieved 2 September 2016.

- ↑ Rafaat, Samir. "Roll-Call of Contributors to the Construction/Maintenance of the Chaar Hachamaim (Adly Street Synagogue)". Historical Society of Jews From Egypt. Retrieved 8 September 2016.

- ↑ "Izmir's Jewish Community Book Collection". Journey into Jewish Heritage - Zalman Shazar Center. Retrieved 2 September 2016.

- ↑ "Family Names". Historical Society of Jews From Egypt. Retrieved 12 September 2016.

- ↑ Abecassis, José Maria. "Genealogia hebraica: Portugal e Gibraltar sécs. XVII a XX". Lisboa: Liv. Ferin. Retrieved 12 September 2016.

- ↑ citation pending from A Man in Three Worlds

- ↑ Vierteljahrschrift für Sozial- und Wirtschaftsgeschichte: Beihefte, Volumes 40-42. W. Kohlhammer. 1923. pp. 139 ("Duarte de Palacios"), 276 ("Duarte Palache"), 403, 404. Retrieved 14 September 2016.

- ↑ "Palache". Les Fleurs de l'Orient. Retrieved 18 November 2016.

- ↑ "Palache, Samuel (archive card number 19260)". Dutch Jewry. Retrieved 30 August 2016.

- 1 2 ) Malka, Jeffrey S. (2002). Sephardi Genealogy. Avotaynu. pp. 293, 349. Retrieved 20 September 2016.

- ↑ Jahrbuch der Jüdisch-Literarischen Gesellschaft, Volumes 6-7. Frankfurt am Main: J. Kauffman. 1909. p. 19. Retrieved 14 September 2016.

- ↑ Jahrbuch der Jüdisch-literarischen Gesellschaft, Volume 10. Frankfurt am Main: J. Kauffmann. 1913. p. 19. Retrieved 14 September 2016.

- ↑ Kellenbenz, Hermann (1958). Sephardim an der unteren Elbe: ihre wirtschaftliche und politische Bedeutung vom Ende des 16. bis zum Beginn des 18. Jahrhunderts. Steiner. pp. 139, 401.

- ↑ "Lista de Appelidos". Nacionalid Sefari. Retrieved 1 September 2016.

- ↑ Auswahl von Grabsteinen auf dem Niederl.-Portug.-Israel: Begräbnisplatze zu Oudekerk an der Amstel: nebst Beschreibung und biographischen Skizzen. Brill. 1883. pp. 22, 27 (quote), 30, 31. Retrieved 14 September 2016.

- ↑ "Palaggi". Les Fleurs de l'Orient. Retrieved 18 November 2016.

- ↑ Zara, Yoram. "P – Sephardic surnames". Sephardic surnames. Retrieved 24 October 2016.

- ↑ Abensur-Hazan, Laurence; Abensur, Phillip. "Sephardic names". ETSI. Retrieved 24 October 2016.

- ↑ Roth, Cecil. "Sephardic names". History of the Jews of Venice. Retrieved 24 October 2016.

- ↑ Galante, Abraham. "Sephardic names". Histoire des Juifs de Rhodes, Chio, Cos, etc. Retrieved 24 October 2016.

- ↑ Benbassa, Esther; Rodrigue, Aron. "Sephardic names". The Jews of the Balkans, The Judeo-Spanish Community , 15th to 20th Centuries. Retrieved 24 October 2016.

- ↑ Faiguenboim, Guilherme; Valadares, Paulo; Campagnano, Anna Rosa. "Sephardic names". Diciionario Sefaradi De Sobrenomes. Retrieved 24 October 2016.

- ↑ "Palacci". Les Fleurs de l'Orient. Retrieved 18 November 2016.

- 1 2 Studia Rosenthaliana. 4–5. Assen: Koninklijke Van Gorcum. 1970. pp. 112 (Palaty), 221 (Palatie). Retrieved 4 September 2016.

- 1 2 "Sephardic Surnames from a number of Jewish Sephardic sources". SephardicGen. Retrieved 8 September 2016.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 19 20 21 22 23 24 25 Laredo, Abraham Isaac (1978). Les noms des juifs de Maroc: Essai d'onomastique judéo-marocaine. Madrid: Consejo Superior de Investigaciones Científicas - Instituto Arias Montano. pp. 966–971.

- ↑ Romeu Ferre, Pilar (2006). "Masa Hayim: Una Homilía de Hayim Palachi" (PDF). Miscelánea de Estudios Árebes y Hebreos (MEAH): Revista del Dpto. de Estudios Semíticos (in Spanish). Granada: Universidad de Granada: 259–273. Retrieved 27 September 2016.

- ↑ Klein, Reuven Chaim; Klein, Shira Yael (2014). Lashon HaKodesh: History, Holiness, & Hebrew. p. 276.

- ↑ Benaim, Annette (2011). Sixteenth-Century Judeo-Spanish Testimonies. p. 517.

- ↑ "Palagi". Les Fleurs de l'Orient. Retrieved 18 November 2016.

- ↑ "Rabbis Buried in Izmir, Turkey, During the Years: 5300 - 5620 (1540 - 1860 C.E.)". SephardicGen Resources. Retrieved 6 September 2016.

- ↑ "Palatchi". Les Fleurs de l'Orient. Retrieved 18 November 2016.

- ↑ Palaggi, Hayyim. The Jewish Encyclopedia. p. 467.

- ↑ Hasida, Yisra'el Yishaq (1961). Rabbi Hayyim Palaji v-sfavarav: Reshima Biyo-Bibliografit, bi-Mlo'ot Me'a Shana li-Ftirato. Jerusalem: Moquire Maran ha-Habif.

- ↑ "Amsterdam Port Isr Gem Burials, Id 19258: Palache, Semuel (Record)". Dutch Jewry. Retrieved 20 October 2016.

- ↑ "Amsterdam Port Isr Gem Burials, Id 19258: Palache, Semuel (File)". Dutch Jewry. Retrieved 20 October 2016.

- ↑ "Palachy". Les Fleurs de l'Orient. Retrieved 18 November 2016.

- ↑ "Palaci". Les Fleurs de l'Orient. Retrieved 18 November 2016.

- ↑ "Burials of the Portuguese Israelite Congregation - Palache, Joseph". Dutch Jewry. Retrieved 8 September 2016.

- ↑ "Begraafplaats Ouderkerk a/d Amstel - Palache, Joseph". Dutch Jewry. Retrieved 8 September 2016.

- ↑ "Burials of the Portuguese Israelite Congregation - Palache, David". Dutch Jewry. Retrieved 8 September 2016.

- ↑ "(untitled - gravestone of David Palache)". Dutch Jewry. Retrieved 8 September 2016.

- ↑ Gottheil, Richard; Seeligmann, Sigmund. "Amsterdam". Jewish Encyclopedia. Retrieved 8 September 2016.

- ↑ "Palache, Judah Lion". Jewish Virtual Library. Retrieved 17 September 2016.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 "Index for Abraham Galante's Jews of Turkey". SephardicGen. Retrieved 6 September 2016.

- ↑ "Annuaire des Juifs de Juifs d'Egypt" (PDF). Cairo: Sephardic Studies. 1943. p. 321. Retrieved 12 September 2016.

- ↑ Fargeon, M. (1938). "Les Juifs en Egypt depuis l'lorigine jusqu'a ce jour (Egypt Jews from the origin till today)" (PDF). Cairo: Sephardic Studies. p. 321. Retrieved 12 September 2016.

- ↑ "Births of the Sephardic Congregation - Kingston, Jamaica, West Indies". Jamaican Family Search. Retrieved 12 September 2016.

- ↑ "Henriette Palatchi". Find a Grave. Retrieved 10 October 2016.

- ↑ "Isaac Palatchi". Find a Grave. Retrieved 10 October 2016.

- ↑ "Isaac Palatchi". Find a Grave. Retrieved 10 October 2016.

.jpg)