Pehlwani

Wrestling match in Davangere (2005) | |

| Also known as | Kushti |

|---|---|

| Focus | Grappling |

| Country of origin |

India Pakistan Bangladesh |

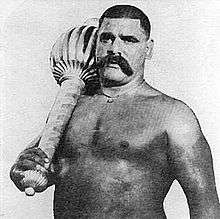

| Famous practitioners |

Babur Nathmal Pahalwan Banda Bahadur Harishchandra Birajdar The Great Gama Jatindra Charan Goho Dara Singh |

| Parenthood |

Malla-yuddha Koshti Pahlavani |

| Olympic sport | No |

| Part of a series on |

| Indian martial arts |

|---|

|

| Styles |

|

| Legendary Figures |

| Notable Practitioners |

| Related terms |

Pehlwani (Urdu/Shahmukhi: پہلوانی, Hindi: पहलवानी, Punjabi: ਪਹਿਲਵਾਨੀ, Bengali: পালোয়ানি) or kushti (Hindi: कुश्ती,Marathi: कुस्ती, Urdu/Shahmukhi: کشتی, Punjabi: ਕੁਸ਼ਤੀ, Bengali: কুস্তি) is a form of wrestling from the Indian Subcontinent. It was developed in the Mughal Empire by combining native malla-yuddha with influences from Persian koshti pahlavani.[1][2] The words pehlwani and kushti derive from the Persian terms pahlavani and koshti respectively.

A practitioner of this sport is referred to as a pehlwan while teachers are known as ustad.[2] Many southern Indian practitioners of traditional malla-yuddha consider their art to be the more "pure" form of Indian wrestling, but most South Asians do not make this clear distinction and simply view kushti as the direct descendent of ancient malla-yuddha, usually downplaying the foreign influence as inconsequential.

History

The ancient South Asian form of wrestling is called malla-yuddha.[2] Practiced at least since the 5th millenniun BC,[3] predating the Indo-Aryan invasions,[4] and described in the 13th century treatise Malla Purana, it was the precursor of modern kushti.[1]

In the 16th century, northern India was conquered by the Central Asian Mughals, who were of Turko-Mongol descent. Through the influence of Iranian and Mongolian wrestling, they incorporated groundwork to the local malla-yuddha, thereby creating modern kushti. Babur, the first Mughal emperor, was a wrestler himself and could reportedly run very fast for a long distance while holding a man under each arm. Mughal-era wrestlers sometimes even wore bagh naka on one hand, in a variation called naki ka kushti or "claw wrestling".

%2C_f.203v_-_BL_Add._27255.jpg)

During the late 17th century, Ramadasa the "father of Indian athletics" travelled the country encouraging Hindus to physical activity in homage to the great god Hanuman. Maratha rulers supported kushti by offering large sums of prize money for tournament champions. It was said that every Maratha boy at the time could wrestle and even women took up the sport. During the colonial period, local princes sustained the popularity of kushti by holding matches and competitions. Wrestling was the favourite spectator sport of the Rajputs, and were said to look forward to tournaments "with great anxiety". Every Rajput prince or chief had a number of wrestling champions to compete for his entertainment. The greatest wrestling centres were said to be Uttar Pradesh and the Panjab.

In 1909, a Bengali merchant named Adbul Jabbar Saudagar intended to unite the local youth and inspire them in the anti-British struggle against the colonists through a display of strength by holding a wrestling tournament. Known as Jabbar-er Boli Khela, this competition has continued through independence and the subsequent partition. It is still held in Bangladesh every Boishakhi Mela (Bengali new year), accompanied by playing of the traditional sanai (flute) and dabor (drum), and is one of Chittagong's oldest traditions.

In the more recent past, India had famous wrestlers of the class of the Great Gama (of British India and later Pakistan, after partition) and Gobar Goho. India reached its peak of glory in the IV Asian Games (later on called Jakarta Games) in 1962 when all the seven wrestlers were placed on the medal list and in between them they won 12 medals in freestyle wrestling and Greco-Roman wrestling. A repetition of this performance was witnessed again when all the 8 wrestlers sent to the Commonwealth Games held at Kingston, Jamaica had the distinction of getting medals for the country. During the 60s, India was ranked among the first eight or nine wrestling nations of the world and hosted the world wrestling championships in New Delhi in 1967.

Pehlwan who compete in wrestling nowadays are also known to cross train in the grappling aspects of judo and jujutsu. Legendary wrestlers from the bygone era like Karl Gotch have made tours to India to learn kushti and further hone their skills. Karl Gotch was even gifted a pair of mudgal (exercise equipment used by South Asian wrestlers). The conditioning exercises of pahlavani have been incorporated into many of the conditioning aspects of both catch wrestling and shoot wrestling, along with their derivative systems. These systems also borrow several throws, submissions and takedowns from kushti.

Training

Regimen

Although wrestling in South Asia saw changes in the Mughal era and the colonial period, the training regimen has remained the same for over 150 years. Fledgeling wrestlers may start as early as 6, but most begin formal training in their teens. They are sent to an akhara or traditional wrestling school where they are put under the apprenticeship of the local guru. Their only training attire is the kowpeenam or loincloth.

Vyayam or physical training is meant to build strength and develop muscle bulk and flexibility. Exercises that employ the wrestler's own bodyweight include the Surya Namaskara, shirshasana, and the danda, which are also found in hatha yoga, as well as the bethak. Sawari (from Persian savâri, meaning "the passenger") is the practice of using another person's bodyweight to add resistance to such exercises.[2]

Exercise regimens may employ the following weight training devices:

- The nal is a hollow stone cylinder with a handle inside.

- The gar nal (neck weight) is a circular stone ring worn around the neck to add resistance to danda and bethak.

- The gada (mace) is a club associated with Hanuman. An exercise gada is a heavy round stone attached to the end of a meter-long bamboo stick. Trophies take the form of gada made of silver and gold.

- Indian clubs, exercise clubs introduced by the Mughals.

Exercise regimens may also include dhakuli which involve twisting rotations, rope climbing, log pulling and running. Massage is regarded an integral part of a wrestler's exercise regimen.

A typical training day will go as follows:

- 3 AM: Wake up and perform press-ups (danda) and squats (bethak), as many as 4000. Run for 5 miles, followed by swimming and lifting stone and sandbags.

- 8 AM: Teachers watch as the trainees wrestle each other in earth pits continuously for 3 hours. This is around 25 matches in a row. Matches start with the senior wrestlers. The youngest go last.

- 10 AM: Wrestlers are given an oil massage before resting.

- 4 PM: After another massage, trainees wrestle each other for another 2 hours.

- 8 PM: The wrestler goes to sleep.

Diet

According to the Samkhya school of philosophy, everything in the universe—including people, activities, and foods—can be sorted into three gunas: sattva (calm/good), rajas (passionate/active), and tamas (dull/lethargic).

As a vigorous activity, wrestling has an inherently rajasic nature, which pehlwan counteract through the consumption of sattvic foods. Milk and ghee are regarded as the most sattvic of foods and, along with almonds, constitute the holy trinity of the pehlwani khurak (from Persian خوراک پهلوانی khorâk-e pahlavâni), or diet. A common snack for pehlwan are chickpeas that have been sprouted overnight in water and seasoned with salt, pepper and lemon; the water in which the chickpeas were sprouted is also regarded as nutritious. Various articles in the Indian wrestling monthly Bharatiya Kushti have recommended the consumption of the following fruits: apples, wood-apples, bananas, figs, pomegranates, gooseberries, lemons, and watermelons. Orange juice and green vegetables are also recommended for their sattvic nature. Some pehlwan eat meat in spite of its tamasic nature.[2]

Ideally, wrestlers are supposed to avoid sour and excessively spiced foods such as chatni and achar as well as chaat. Mild seasoning with garlic, cumin, coriander, and turmeric is acceptable. The consumption of alcohol, tobacco, and paan is strongly discouraged.[2]

Techniques

It has been said that most of the moves found in the wrestling forms of other countries are present in kushti, and some are unique to South Asia. These are primarily locks, throws, pins, and submission holds. Unlike its ancient ancestor malla-yuddha, kushti does not permit strikes or kicks during a match. Among the most favoured maneuvres are the dhobi paat (shoulder throw) and the kasauta (strangle pin). Other moves include the baharli, dhak, machli gota and the multani.

Rules

.jpg)

Wrestling competitions, known as dangal or kushti, are held in villages and as such are variable and flexible. The arena is either a circular or square shape, measuring at least fourteen feet across. Rather than using modern mats, South Asian wrestlers train and compete on dirt floors. Before training, the floor is raked of any pebbles or stones. Buttermilk, oil, and red ochre are sprinkled to the ground, giving the dirt its red hue. Water is added every few days to keep it at the right consistency; soft enough to avoid injury but hard enough so as not to impede the wrestlers' movements. Every match is preceded by the wrestlers throwing a few handfuls of dirt from the floor on themselves and their opponent as a form of blessing. Despite the marked boundaries of the arena, competitors may go outside the ring during a match with no penalty. There are no rounds but the length of every bout is specified beforehand, usually about 25–30 minutes. If both competitors agree, the length of the match may be extended. Match extensions are typically around 10–15 minutes.[5] A win is achieved by pinning the opponent's shoulders and hips to the ground simultaneously, although victory by knockout, stoppage or submission is also possible. In some variations of the rules, only pinning the shoulders down is enough. Bouts are overseen by a referee inside the ring and a panel of two judges watching from the outside.

Titles

Official titles awarded to kushti champions are as follows. Note that the title Rustam is actually the hero's name of the Persian Shahnameh epic.

- "Rustam-e-Hind": Champion Of India. Dara Singh from Punjab, Krishan Kumar from Haryana, Muhammad Buta Pehlwan, Imam Baksh Pehlwan, Hamida Pehlwan, Vishnupant Nagrale, Dadu Chaugle and Harishchandra Birajdar (Lion of India)[6] from Maharashtra, Mangla Rai from Uttar Pradesh and Pehlwan Shamsher Singh (Punjab Police) held the Rustam-e-Hind title in the past. Vishnupant Nagrale was the first wrestler ever to hold this title.

- "Maharashtra Kesari": Lion of Maharashtra. Maharashtra Kesari is an Indian-style wrestling championship. Narsinh Yadav (three-time winner)[7]

- "Rustam-e-Panjaab" : (also spelled Rustam-i-Panjab) Champion of Panjab. Pehlwan Shamsher Singh (Punjab Police) Pehlwan Salwinder Singh Shinda was a six time Rustam-e-Panjab,.

- "Rustam-e-Zamana": World Champion. The Great Gama became known as Rustam-e-Zamana when he defeated Stanislaus Zbyszko in 1910.

- "Bharat-Kesari": Best heavyweight wrestler in Hindi. Recent winners include Krishan Kumar(1986), Rajeev Tomar (Railways), Pehlwan Shamsher Singh (Punjab Police) and Palwinder Singh Cheema (Punjab police).,

- "Hind Kesari": Winner of 1969 Hind Kesari Harishchandra Birajdar (Maharashtra)[8] (Lion of India);[6] Winner of 2013 Hind Kesari, Amol Barate (Maharashtra);[9] Winner of 2015 Hind Kesari, Sunil Salunkhe (Maharashtra)[10]

See also

References

- 1 2 Alter, Joseph S. (May 1992a). "The "sannyasi" and the Indian Wrestler: The Anatomy of a Relationship". American Ethnologist. 19 (2): 317–336. doi:10.1525/ae.1992.19.2.02a00070. ISSN 0094-0496.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 Alter, Joseph S. (1992b). The Wrestler's Body: Identity and Ideology in North India. Berkeley: University of California Press. ISBN 0-520-07697-4.

- ↑ Alter, Joseph S. (May 1992). "the sannyasi and the Indian wrestler: the anatomy of a relationship". American Ethnologist. 19 (2): 317–336. doi:10.1525/ae.1992.19.2.02a00070. ISSN 0094-0496.

- ↑ Donn F. Draeger and Robert W. Smith (1969). Comprehensive Asian Fighting Arts. Kodansha International Limited.

- ↑ "Jabbar-er Boli Khela and Baishakhi Mela in Chittagong". archive.thedailystar.net. April 28, 2010. Retrieved June 8, 2013.

- 1 2 "Olympian wrestler 'Lion of India' Harishchandra Birajdar passes away". dna. 14 September 2011.

- ↑ "Narsing is 'Maharashtra Kesari' for record third time | Sakal Times". Sakaaltimes.com. Retrieved 2016-01-10.

- ↑ "Wrestler Harishchandra Birajdar dies at 73 - Indian Express". Archive.indianexpress.com. 2011-09-15. Retrieved 2016-01-10.

- ↑ "Pune boy Barate is Hind Kesari | Sakal Times". Sakaaltimes.com. Retrieved 2016-01-10.

- ↑ क्रीडा (2015-02-02). "सुनील साळुंखे 'हिंद केसरी'". Loksatta.com. Retrieved 2016-01-10.

External links

- The Wrestler’s Body: Identity and Ideology in North India

- Pakistan's pehlwans wrestle to survive

- Pakistan Image Building: History of Kushti

- Dara Singh In The Wrestling Observer Hall of Fame

- Great Gama

- Upper Crust: Badam-Doodh & Kolhapuri Kusti!

- The Art of Pehlwani

- Fighting Scene in Indian Cinemas