People's Crusade

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

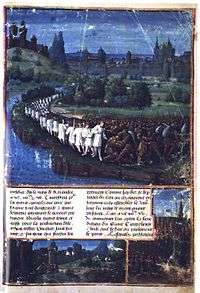

The People's Crusade was the prelude to the First Crusade and lasted roughly six months from April to October 1096. It is also known as the Peasants' Crusade, Paupers' Crusade or the Popular Crusade as it was not part of the official Catholic Church-organised expeditions that came later. Led primarily by Peter the Hermit with forces of Walter Sans Avoir, the army was destroyed by the Seljuk forces of Kilij Arslan at Civetot, northwestern Anatolia.

Historically, there has been much debate over whether Peter was the real initiator of the Crusade as opposed to Pope Urban II. The expedition's independence has been used by some historians such as Hagenmeyer to prove this.

Background

Pope Urban II planned the departure of the crusade for 15 August 1096; before this, a number of unexpected bands of peasants and low-ranking knights organized and set off for Jerusalem on their own. The peasant population had been afflicted by drought, famine, and disease for many years before 1096, and some of them seem to have envisioned the crusade as an escape from these hardships. Spurring them on had been a number of meteorological occurrences beginning in 1095 that seemed to be a divine blessing for the movement: a meteor shower, aurorae, a lunar eclipse, and a comet, among other events. An outbreak of ergotism had also occurred just before the Council of Clermont. Millenarianism, the belief that the end of the world was imminent, popular in the early 11th century, experienced a resurgence in popularity. The response was beyond expectations: while Urban might have expected a few thousand knights, he ended up with a migration numbering up to 15,000 Crusaders of mostly unskilled fighters, including women and children.[5]

A charismatic monk and powerful orator named Peter the Hermit of Amiens was the spiritual leader of the movement. He was known for riding a donkey and dressing in simple clothing. He had vigorously preached the crusade throughout northern France and Flanders. He claimed to have been appointed to preach by Christ himself (and supposedly had a divine letter to prove it), and it is likely that some of his followers thought he, not Urban, was the true originator of the crusading idea. It is often believed that Peter's army was a band of illiterate, incompetent peasants who had no idea where they were going, and who believed that every city of any size they encountered on their way was Jerusalem itself; this may have been true for some, but the long tradition for pilgrimages to Jerusalem ensured that the location and distance of the city were well known. While the majority were unskilled in fighting, there were some well-trained minor knights leading them, such as Walter Sans-Avoir (also mistakenly known as Walter the Penniless[7]), who was experienced in warfare.

Massacre of Jews in Central Europe

In the late spring and summer of 1096, crusaders destroyed most of the Jewish communities along the Rhine in a series of unprecedentedly large pogroms in France and Germany in which thousands of Jews were massacred, driven to suicide, or forced to convert to Christianity.[8][9][10][8] Eleven Jews were murdered in Speyer, where the Bishop saved the rest of the Jews for a large payment, but in Worms some 800 were murdered. In Mainz, over one thousand Jews were murdered, as well as more in Trier, Metz, Cologne, and elsewhere. Others were subjected to forced baptism and conversion. The preacher Folkmar and Count Emicho of Flonheim were the main inciters and leaders of the massacre. The major chroniclers of the 1096 killings are Solomon bar Simson and Albert of Aachen.[11][10][8][12]

Estimates of the number of Jewish men, women, and children murdered or driven to suicide by crusaders vary, ranging from 2,000 to 12,000.[13][14] Julius Aronius put the number killed at 4,000, regarding other figures as too high.[13] Norman Cohn puts the number at between 4,000 and 8,000 from May to June 1096.[11] Gedaliah ibn Yahya estimated that some 5,000 Jews were killed from April to June 1096.[15] Edward H. Flannery's estimate is that 10,000 were murdered over the longer January-to-July period, "probably one-fourth to one-third of the Jewish population of Germany and Northern France at that time."[16]

The Church opposed these attacks, and local clergy often came to the defense of Jews in their community.[17] The pogroms were decried by many Christians of the day. Some even pointed to these crimes as the reason God forsook their fellow crusaders at Nicaea and Civetot. [18]

Walter and the French

Peter gathered his army at Cologne on 12 April 1096, planning to stop there and preach to the Germans and gather more crusaders. The French, however, were not willing to wait for Peter and the Germans and under the leadership of Walter Sans Avoir, a few thousand French crusaders left before Peter and reached Hungary on 8 May, passing through Hungary without incident and arriving at the river Sava at the border of Byzantine territory at Belgrade. The Belgrade commander was taken by surprise, having no orders on what to do with them, and refused entry, forcing the crusaders to pillage the countryside for food. This resulted in skirmishes with the Belgrade garrison and, to make matters worse, sixteen of Walter's men had tried to rob a market in Zemun across the river in Hungary and were stripped of their armor and clothing, which was hung from the castle walls. Eventually the crusaders were allowed to carry on to Niš, where they were provided with food and waited to hear from Constantinople.

Cologne to Constantinople

Peter and the remaining crusaders left Cologne about 20 April. About 40,000 Crusaders left immediately, while another group would follow soon after (see the German Crusade).[5] When they reached the Danube, part of the army decided to continue on by boat down the Danube, while the main body continued overland and entered Hungary at Sopron. There it continued through Hungary without incident and rejoined the Danube contingent at Zemun on the Byzantine frontier.

In Zemun, the crusaders became suspicious, seeing Walter's sixteen suits of armor hanging from the walls, and eventually a dispute over the price of a pair of shoes in the market led to a riot, which then turned into an all-out assault on the city by the crusaders, in which 4,000 Hungarians were killed. The crusaders then fled across the river Sava to Belgrade, but only after skirmishing with Belgrade troops. The residents of Belgrade fled, and the crusaders pillaged and burned the city. Then they marched for seven days, arriving at Niš on 3 July. There, the commander of Niš promised to provide escort for Peter's army to Constantinople as well as food, if he would leave right away. Peter obliged, and the next morning he set out. However, a few Germans got into a dispute with some locals along the road and set fire to a mill, which escalated out of Peter's control until Niš sent out its entire garrison against the crusaders. The crusaders were completely routed, losing about 10,000 (a quarter of their number), the remainder regrouping further on at Bela Palanka.[5] When they reached Sofia on 12 July they met their Byzantine escort, which brought them safely the rest of the way to Constantinople by 1 August.

Leadership breakdown

Byzantine Emperor Alexius I Comnenus, not knowing what else to do with such an unusual and unexpected "army", quickly ferried all 30,000 across the Bosporus by 6 August.[19] It has since been debated whether he sent them away without Byzantine guides knowing full well that they could be slaughtered by the Turks, or whether they insisted on continuing into Asia Minor despite his warnings. In any case, it is known that Alexius warned Peter not to engage the Turks, whom he believed to be superior to Peter's motley army, and to wait for the main body of crusaders, which was still on the way.[20]

Peter was rejoined by the French under Walter Sans-Avoir and a number of bands of Italian crusaders who had arrived at the same time. Once in Asia Minor, they began to pillage towns and villages until they reached Nicomedia, where an argument broke out between the Germans and Italians on one side and the French on the other. The Germans and Italians split off and elected a new leader, an Italian named Rainald, while for the French, Geoffrey Burel took command. Peter had effectively lost control of the crusade.

Even though Alexius had urged Peter to wait for the main army, Peter had lost much of his authority and the crusaders spurred each other on, moving more boldly against nearby towns until finally the French reached the edge of Nicaea, a Seljuk stronghold and provincial capital, where they pillaged the suburbs. The Germans, not to be outdone, marched with 6,000 crusaders on Xerigordon and captured the city to use as a base to raid the countryside. In response, the Turks, led by one of Kilij Arslan's generals, recovered Xerigordon[6] from the crusaders, who were forced to drink the blood of donkeys and their own urine during the siege, since their water supply was cut. Some of the crusaders who were captured converted to Islam and were sent to Khorasan, while others who refused to abandon their faith were killed.[21]

Battle and outcome

Back at the main crusaders' camp, two Turkish spies had spread rumor that the Germans who had taken Xerigordon had also taken Nicaea, which caused excitement to get there as soon as possible to share in the looting. Of course, the Turks were waiting on the road to Nicaea. Peter the Hermit had gone back to Constantinople to arrange for supplies and was due back soon, and most of the leaders argued to wait for him to return (which he never did). However, Geoffrey Burel, who had popular support among the masses, argued that it would be cowardly to wait, and they should move against the Turks right away. His will prevailed and, on the morning of 21 October, the entire army of 20,000 marched out toward Nicaea, leaving women, children, the old and the sick behind at the camp.[4]

Three miles from the camp, where the road entered a narrow, wooded valley near the village of Dracon, the Turkish army was waiting. When approaching the valley, the crusaders marched noisily and were immediately subjected to a hail of arrows.[22] Panic set in immediately and within minutes, the army was in full rout back to the camp. Most of the crusaders were slaughtered; however, women, children, and those who surrendered were spared. Three thousand, including Geoffrey Burel, were able to obtain refuge in an abandoned castle. Eventually the Byzantines under Constantine Katakalon sailed over and raised the siege; these few thousand returned to Constantinople, the only survivors of the People's Crusade.[23]

See also

References

- ↑ John France, Victory in the East: A Military History of the First Crusade, (Cambridge University Press, 1997), pg. 159

- ↑ Paul L. Williams, The Complete Idiot's Guide to the Crusades, pg. 48

- ↑ Tom Campbell, Rights: A Critical Introduction, pg. 71

- 1 2 J. Norwich, Byzantium: The Decline and Fall, 35

- 1 2 3 4 J. Norwich, Byzantium: The Decline and Fall, 33

- 1 2 Jim Bradbury, The Routledge Companion to Medieval Warfare, pg. 186

- ↑ Jonathan Riley-Smith, The Crusades: A History, 2nd ed. (Yale University Press, 2005), pg. 27

- 1 2 3 Nikolas Jaspert, The Crusades. Routledge, 2006: 39–40.

- ↑ Gerd Mentgen, "Crusades" in Antisemitism: A Historical Encyclopedia of Prejudice and Persecution (Vol. 1), ed. Richard S. Levy, 151-53.

- 1 2 Jonathan Phillips, Holy Warriors: A Modern History of the Crusades. Random House, 2010: 9–10.

- 1 2 Norman Cohn, The Pursuit of the Millennium: Revolutionary Millenarians and Mystical Anarchists of the Middle Ages. Oxford University Press, 1970: 69–70.

- ↑ Gerd Mentgen, "Crusades" in Antisemitism: a Historical Encyclopedia of Prejudice and Persecution (Vol. 1), ed. Richard S. Levy, 151-53.

- 1 2 Jits van Straten, Jewish Migrations from Germany to Poland: the Rhineland Hypothesis Revisited, Mankind Quarterly 44 (2003).

- ↑ Simon Dubno and Moshe Spiegel, History of the Jews: From the Roman Empire to the Early Medieval Period (Vol. 2). Associated University Presse, 1980: 677.

- ↑ Rodney Stark, One True God: Historical Consequences of Monotheism. Princeton University Press, 2003: 140–41

- ↑ Edward H. Flannery, The Anguish of the Jews: Twenty-Three Centuries of Antisemitism. Paulist Press, 1985: 93.

- ↑ "Archived copy". Archived from the original on 2014-10-06. Retrieved 2014-07-27. The Church and the Jews in the Middle Ages

- ↑ http://historymedren.about.com/od/firstcrusade/p/The-Peoples-Crusade.htm The People's Crusade History

- ↑ J. Norwich, Byzantium: The Decline and Fall, 34

- ↑ http://historymedren.about.com/od/firstcrusade/p/The-Peoples-Crusade.htm The People's Crusade History

- ↑ Steven Runciman, The First Crusade, pg. 59

- ↑ Steven Runciman, The First Crusade, pg. 60

- ↑ Skoulatos, Basile (1980). Les personnages byzantins de I'Alexiade: Analyse prosopographique et synthese (in French). p. 64

- Peter the Hermit and the People's Crusade: Collected Accounts.

- Duncalf, Frederic. "The Peasants Crusade." American Historical Review 26 (1921): pg. 440–453.

- Cohn, Norman. The Pursuit of the Millennium.

- See also First Crusade – selected sources and further reading