İznik

| İznik | |

|---|---|

İznik | |

| Coordinates: 40°25′45″N 29°43′16″E / 40.42917°N 29.72111°ECoordinates: 40°25′45″N 29°43′16″E / 40.42917°N 29.72111°E | |

| Country |

|

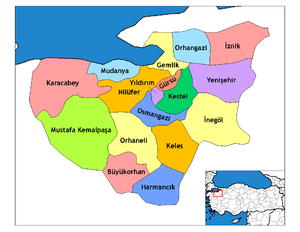

| Province | Bursa |

| Government | |

| • Mayor | Osman Sargın (AKP) |

| • Kaymakam | Hüseyin Karameşe |

| Area[1] | |

| • District | 736.51 km2 (284.37 sq mi) |

| Population (2012)[2] | |

| • Urban | 22,507 |

| • District | 43,425 |

| • District density | 59/km2 (150/sq mi) |

| Post code | 16860 |

| Website |

www |

İznik is a town and an administrative district in the Province of Bursa, Turkey.[3] It was historically known as Nicaea (Greek: Νίκαια), from which its modern name also derives. The town lies in a fertile basin at the eastern end of Lake İznik, bounded by ranges of hills to the north and south. As the crow flies, the town is only 90 kilometres (56 miles) southeast of Istanbul but by road it is 200 km (124 miles) around the Gulf of Izmit. It is 80 km (50 miles) by road from Bursa.

The town is situated with its west wall rising from the lake itself, providing both protection from siege from that direction, as well as a source of supplies which would be difficult to cut off. The lake is large enough that it cannot be blockaded from the land easily, and the city was large enough to make any attempt to reach the harbour from shore-based siege weapons very difficult.

The city was surrounded on all sides by 5 km (3 mi) of walls about 10 m (33 ft) high. These were in turn surrounded by a double ditch on the land portions, and also included over 100 towers in various locations. Large gates on the three landbound sides of the walls provided the only entrance to the city.

Today the walls are pierced in many places for roads, but much of the early work survives and as a result it is a tourist destination. The town has a population of about 15,000. It has been a district center of Bursa Province since 1930. It was in the district of Kocaeli between 1923 and 1927 and was a township of Yenişehir (bound to Bilecik before 1926) district between 1927 and 1930.

The town was an important producer of highly decorated fritware vessels and tiles in the 16th and 17th centuries.

History

- For the history before the Ottoman conquest, see the article on Nicaea.

In 1331, Orhan I captured the city from the Byzantines and for a short period the town became the capital of the expanding Ottoman emirate.[4] The large church of Hagia Sophia in the centre of the town was converted into a mosque and became known as the Orhan Mosque.[5] A madrasa and baths were built nearby.[6] In 1334 Orhan built a mosque and an imaret (soup kitchen) just outside the Yenisehir gate (Yenişeh Kapısı) on the south side of the town.[7]

The Moroccan traveller Ibn Battuta stayed in Iznik at the end of 1331 soon after the capture of the town by Orhan.[8] According to Ibn Battuta, the town was in ruins and only inhabited by a small number of people who were in the service of the sultan. Within the city walls were gardens and cultivated plots with each house surrounded by an orchard. The town produced fruit, walnuts, chestnuts and large sweet grapes.[7][9]

A census in 1520 recorded 379 Muslim and 23 Christian households while a census taken a century later in 1624 recorded 351 Muslim and 10 Christian households. Assuming five members for each household, these figures suggest that the population was around 2,000. Various estimates in the 18th and 19th centuries give similar numbers.[10] The town was poor and the population small even when the ceramic production was at its peak during the second half of the 16th century.[11]

The Byzantine city is estimated to have had a population of 20,000–30,000 but in the Ottoman period the town was never prosperous and occupied only a small fraction of the walled area. A succession of visitors described the town in unflattering terms. After his visit in 1779, the Italian archaeologist Domenico Sestini wrote that Iznik was nothing but an abandoned town with no life, no noise and no movement.[7][12] In 1797 James Dallaway described Iznik as "a wretched village of long lanes and mud walls...".[7][13] Most of the remainder of the town was destroyed during 1921 in the Greco-Turkish War (1919–1922); the population became refugees and many historical buildings were damaged or destroyed.[14]

Pottery and tiles

The town became a major center with the creation of a local faïence pottery-making industry during the Ottoman period in the 16th century, known as the İznik Çini. Iznik ceramic tiles were used to decorate many of the mosques in Istanbul designed by Mimar Sinan. However, this industry declined in the 17th century[15] and İznik became a mainly agricultural minor town in the area when a major railway bypassed it in the 19th century. Currently the style of pottery referred to as the İznik Çini is to some extent produced locally, but mainly in Kütahya, where the quality – which was in decline – has been restored to its former glory.

Surviving monuments

A number of monuments were erected by the Ottomans in the period between the conquest in 1331 and 1402 when the town was sacked by Timur. Among those that have survived are:

- Hacı Özbek Mosque (1333). This mosque was built only three years after the conquest. The portico on the west side of the building was demolished in 1940 to widen the road.[16]

- Yeşil Mosque of Iznik Green Mosque (1378–1391). The mosque was built for Çandarlı Kara Halil Hayreddin Pasha, the first Grand Vizier of the Ottoman Empire. It is located near the Lefke Gate on the east side of the town. It was damaged in 1922 during the Greco-Turkish War and restored between 1956 and 1969.[7][17]

- Hagia Sophia also known as Aya Sofya (Greek: Ἁγία Σοφία, "Holy Wisdom") is a Byzantine-era former church building which was built by Justinian I in the middle of the city in the 6th century.[18]

- Nilüfer Hatun Soup Kitchen (Nilüfer Hatun Imareti) (1388). The building was abandoned for many years but was restored in 1955 and is now a museum.[19]

- Süleyman Pasa Madrasa (mid 14th century). This is one of the two surviving madrasas in the town. It was restored in the 19th century and again in 1968.[20]

- Mausoleum of Çandarli Hayreddin Pasa (14th century). The main room contains fifteen sarcophagi. A lower room contains three more sarcophagi including that of Hayreddin Pasha. The mausoleum is located in a cemetery outside the Lefke gate to the east of the town.[21]

Several monuments survived into the 20th century but were destroyed during the Greco-Turkish War (1919–1922). These include:

- Church of the Koimesis/Dormition (6th–8th century but rebuilt after the 1065 earthquake). This was the only church in the town that was not transformed into a mosque.[22] It was decorated with 11th century Byzantine mosaics of which photographs survive.[23][24]

- Eşrefzâde Rumi Mosque (15th century). Eşrefzâde Rumi was married to the daughter of Hacı Bayram-ı Veli. He founded a sufi sect and after his death in 1469–70 his tomb became a pilgrimage site.[7] The mosque was decorated with Iznik tiles.[25]

- Seyh Kutbeddin Mosque and Mausoleum (15th century). The mausoleum has been rebuilt.[26]

Sport

The İznik Ultramarathon is a 130 km (81 mi) trail endurance running event that takes place around Lake İznik in April since 2012 as the country's longest single-stage athletics competition.[27]

International relations

Twin towns – sister cities

İznik is twinned with:

Spandau / Berlin, Germany

Notes

- ↑ "Area of regions (including lakes), km²". Regional Statistics Database. Turkish Statistical Institute. 2002. Retrieved 2013-03-05.

- ↑ "Population of province/district centers and towns/villages by districts - 2012". Address Based Population Registration System (ABPRS) Database. Turkish Statistical Institute. Retrieved 2013-02-27.

- ↑ Lonely Planet Turkey ed. Verity Campbell 2007 Page 291 "Original İznik tiles are antiquities and cannot be exported from Turkey, but new tiles make great, if not particularly cheap, souvenirs."

- ↑ Raby 1989, p. 19–20.

- ↑ Tsivikis, Nikolaos (23 March 2007), "Nicaea, Church of Hagia Sophia", Encyclopaedia of the Hellenic World, Asia Minor, Foundation of the Hellenic World, retrieved 20 September 2014.

- ↑ St. Sophia Museum, ArchNet, retrieved 20 September 2014.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 Raby 1989, p. 20.

- ↑ Dunn 2005, p. 158 note 20. Raby (1989, p. 20) suggests a date between 1334 and 1339.

- ↑ Defrémery & Sanguinetti 1854, pp. 323–324; Gibb 1962, p. 453

- ↑ Raby 1989, pp. 20–21.

- ↑ Raby 1989, p. 21.

- ↑ Sestini 1789, pp. 219–220.

- ↑ Dallaway 1797, p. 169.

- ↑ Uyan, Ayhan (28 November 2011), İznik’te Milli Mücadelede Yunan Tahribatı, iznikrehber.com, retrieved 19 June 2013

- ↑ http://mini-site.louvre.fr/trois-empires/en/ceramiques-ottomanes.php

- ↑ Haci Özbek Mosque, ArchNet, retrieved 20 September 2014.

- ↑ Green Mosque, ArchNet, retrieved 20 September 2014.

- ↑ Hazlitt, Classical Gazetteer, "Nicæa"

- ↑ Nilüfer Hatun Soup Kitchen, ArchNet, retrieved 20 September 2014.

- ↑ Süleyman Pasa Madrasa, ArchNet, retrieved 20 September 2014.

- ↑ Tomb of Çandarli Hayreddin Pasa, ArchNet, retrieved 20 September 2014.

- ↑ Kastrinakis, Nikos (16 June 2005), "Nicaea (Byzantium), Dormition Church", Encyclopaedia of the Hellenic World, Asia Minor, Foundation of the Hellenic World, retrieved 20 September 2014.

- ↑ Mango 1959.

- ↑ Kanaki, Elena (22 June 2005), "Nicaea (Byzantium), Church of the Dormition, Mosaics", Encyclopaedia of the Hellenic World, Asia Minor, Foundation of the Hellenic World, retrieved 20 September 2014.

- ↑ Esrefzade Rumi Mosque, ArchNet, retrieved 20 September 2014.

- ↑ Seyh Kutbeddin Mosque and Tomb, ArchNet, retrieved 20 September 2014.

- ↑ "İznik'te maraton heyecanı başladı". Sabah (in Turkish). 2012-04-14. Retrieved 2013-11-26.

- ↑ "Twinnings" (PDF). Central Union of Municipalities & Communities of Greece. Retrieved 2013-08-25.

References

- Dallaway, James (1797), Constantinople Ancient and Modern: with excursions to the shores and islands of the archipelago and to the Troad, London: T. Cadell, junr. & W. Davies.

- Defrémery, C.; Sanguinetti, B.R. trans. and eds. (1854), Voyages d'Ibn Batoutah, Volume 2 (in Arabic and French), Paris: Société Asiatic.

- Dunn, Ross E. (2005), The Adventures of Ibn Battuta, University of California Press, ISBN 0-520-24385-4. First published in 1986, ISBN 0-520-05771-6.

- Gibb, H.A.R. trans. and ed. (1962), The Travels of Ibn Baṭṭūṭa, A.D. 1325–1354 (Volume 2), London: Hakluyt Society.

- Mango, Cyril (1959), "The date of the narthex mosaics of the Church of the Dormition at Nicaea", Dumbarton Oaks Papers, 13: 245–252, JSTOR 1291137.

- Raby, Julian (1989), "İznik, 'Une village au milieu des jardins'", in Petsopoulos, Yanni, Iznik: The Pottery of Ottoman Turkey, London: Alexandra Press, pp. 19–22, ISBN 978-1-85669-054-6.

- Sestini, Domenico (1789), Voyage dans la Grèce asiatique, à la péninsule de Cyzique, à Brusse et à Nicée: avec des détails sur l'histoire naturelle de ces contrées (in French), London and Paris: Leroy.

Further reading

- Alioğlu, E. Fusun (2001), "Similarities between early Ottoman architecture and local architecture or Byzantine architecture in Iznik", ICOMOS International Millennium Congress. More than two thousand years in the history of architecture, Session 2, Historic Towns (PDF), UNESCO-ICOMOS.

- Alioğlu, E.Fusun (2001), "Establishing the sustainable identity of a historical city field of research: Iznik", ICOMOS International Millennium Congress. More than two thousand years in the history of architecture, Session 2, Historic Towns (PDF), UNESCO-ICOMOS.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to İznik. |

-

Iznik travel guide from Wikivoyage

Iznik travel guide from Wikivoyage - Iznik, ArchNet. Information on the historic buildings in the town.

- Photographs of the town taken in 2007 by Dick Osseman