Prehistoric Indonesia

Prehistoric Indonesia is a prehistoric period in the Indonesian archipelago that spanned from the Pleistocene period to about the 4th century CE when the Kutai people produced the earliest known stone inscriptions in Indonesia.[1] Unlike the clear distinction between prehistoric and historical periods in Europe and the Middle East, the division is muddled in Indonesia. This is mostly because Indonesia's geographical conditions as a vast archipelago caused some parts — especially the interiors of distant islands — to be virtually isolated from the rest of the world. West Java and coastal Eastern Borneo, for example, began their historical periods in the early 4th century, but megalithic culture still flourished and script was unknown in the rest of Indonesia, including in Nias, Batak, and Toraja. The Papuans on the Indonesian part of New Guinea island lived virtually in the stone age until their first contacts with modern world in early 20th century. Even today living megalithic traditions still can be found on the island of Sumba and Nias.

Geology

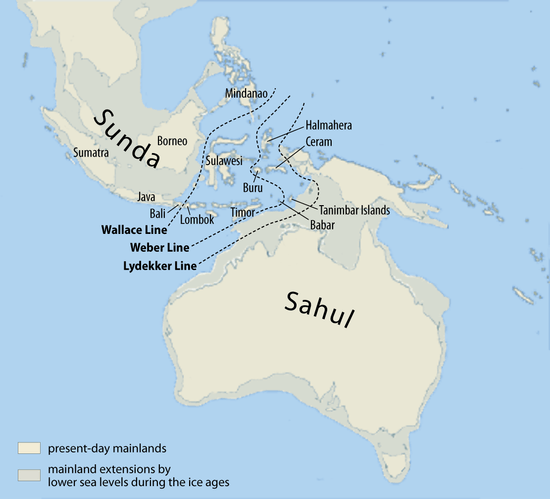

Geologically, the area of modern Indonesia appeared from under the Southeast Asian seas as the result of the Indian and Australian plates colliding and slipping under the Sunda Plate, sometime in the early Cenozoic era around 63 million years ago.[2] This tectonic collision created Sunda volcanic Arc that has produced chains of islands of Sumatra, Java and the Lesser Sunda Islands. The active volcanic arc creating supervolcano that today become Lake Toba in Sumatra. The massive eruption of Toba supervolcano that occurred some time between 69,000 and 77,000 years ago instigated the Toba catastrophe theory, a global volcanic winter that caused a bottleneck in human evolution. Other notable volcanoes in Sunda Arc are Mount Tambora and Krakatau. The region is known for its instability due to volcano formations and other volcanic and tectonic activities as well as climate changes; resulted in lowlands drowned occasionally under shallow seas, the formation of islands, the connection and disconnection of islands through narrow land-bridges, etc.

The Indonesian archipelago nearly reached its present form in the Pleistocene period. For some periods, the Sundaland was still linked with Asian mainland, creating the landmass extension of Southeast Asia that enabled the migrations of some Asian animals and hominid species. Geologically the New Guinea island and the shallow seas of Arafura is the northern part of Australia tectonic plate and once connected as a land bridge identified as Sahulland. During the end of the last ice age (around 20,000–10,000 years ago), earth experienced global climate change; a global warming with the rising of average temperature caused the melting of polar ice caps and contributed to the rising of sea surface. Sundaland was submerged under shallow sea, creating Malacca Strait, South China Sea, Karimata Strait and Java Sea. During that period, Malay peninsula, Sumatra, Java, Borneo and the islands around them were formed. On the east, New Guinea and Aru Islands were separated from the Australia mainland. The rise of sea surface created isolated areas that separated plants, animals and hominid species, causing further evolution and specification.

Human migration

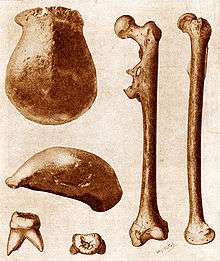

In 2007 analysis of cut marks on two bovid bones found in Sangiran, showed them to have been made 1.5 to 1.6 million years ago by clamshell tools, and is the oldest evidence for the presence of early man in Indonesia. Fossilised remains of Homo erectus, popularly known as the "Java Man" were first discovered by the Dutch anatomist Eugène Dubois at Trinil in 1891, and are at least 700,000 years old, at that time the oldest human ancestor ever found. Further Homo erectus fossils of a similar age were found at Sangiran in the 1930s by the anthropologist Gustav Heinrich Ralph von Koenigswald, who in the same time period also uncovered fossils at Ngandong alongside more advanced tools, re-dated in 2011 to between 550,000 and 143,000 years old.[3][4] In 1977 another Homo erectus skull was discovered at Sambungmacan.[5]

In 2003, on the island of Flores, fossils of a new small hominid dated between 74,000 and 13,000 years old and named "Flores Man" (Homo floresiensis) were discovered much to the surprise of the scientific community.[6] This 3 foot tall hominid is thought to be a species descended from Homo Erectus and reduced in size over thousands of years by a well known process called island dwarfism. Flores Man seems to have shared the island with modern Homo sapiens until only 12,000 years ago, when they became extinct. In 2010 stone tools were discovered on Flores dating from 1 million years ago, which is the oldest evidence anywhere in the world that early man had the technology to make sea crossings at this very early time.[7]

The archipelago was formed during the thaw after the latest ice age. Early humans travelled by sea and spread from mainland Asia eastward to New Guinea and Australia. Homo sapiens reached the region by around 45,000 years ago.[8] In 2011 evidence was uncovered in neighbouring East Timor, showing that 42,000 years ago these early settlers had high-level maritime skills, and by implication the technology needed to make ocean crossings to reach Australia and other islands, as they were catching and consuming large numbers of big deep-sea fish such as tuna.[9]

Around 2000 BCE there was an expansion of seafaring Austronesian people from Asia, who spread throughout Maritime Southeast Asia to Madagascar and Oceania. Austronesian people form the majority of the modern population.[10]

Chronology

Paleolithic

Homo erectus were known to utilise simple coarse paleolithic stone tools and also shell tools, discovered in Sangiran and Ngandong. Cut mark analysis of Pleistocene mammalian fossils documents 18 cut marks inflicted by tools of thick clamshell flakes on two bovid bones created during butchery at the Pucangan Formation in Sangiran between 1.6 and 1.5 million years ago. These cut marks document the use of the first tools in Sangiran and the oldest evidence of shell tool use in the world.[11]

Neolithic

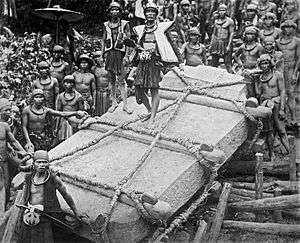

The polished stone tools of neolithic culture, such as polished stone axes and stone hoes, were developed by the Austronesian people in the Indonesian archipelago. Also during the neolithic period, large stone structures of the megalithic culture flourished in archipelago.

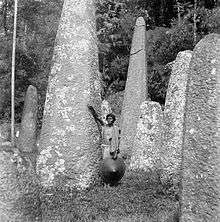

Megalithic

The Indonesian archipelago is the host of Austronesian megalith cultures both past and present. Several megalith sites and structures are also found across Indonesia. Menhirs, dolmens, stone tables, ancestral stone statues, and step pyramid structure called Punden Berundak were discovered in various sites in Java, Sumatra, Sulawesi, and the Lesser Sunda Islands.

Punden step pyramid and menhir can be found in Pagguyangan Cisolok and Gunung Padang, West Java. Cipari megalith site also in West Java displayed monolith, stone terraces, and sarcophagus.[12] The Punden step pyramid is believed to be the predecessor and basic design of later Hindu-Buddhist temples structure in Java after the adoption of Hinduism and Buddhism by the native population. The 8th century Borobudur and 15th-century Candi Sukuh featured the step-pyramid structure.

Lore Lindu National Park in Central Sulawesi houses ancient megalith relics such as ancestral stone statues. Mostly located in the Bada, Besoa and Napu valleys.[13]

Living megalith cultures can be found on Nias, an isolated island off the western coast of North Sumatra, the Batak people in the interior of North Sumatra, on Sumba island in East Nusa Tenggara and also Toraja people from the interior of South Sulawesi. These megalith cultures remained preserved, isolated and undisturbed well into the late 19th century.

Bronze age

Dong Son culture spread to Indonesia bringing with it techniques of bronze casting, wet-field rice cultivation, ritual buffalo sacrifice, megalithic practises, and ikat weaving methods. Some of these practices remain in areas including the Batak areas of Sumatra, Toraja in Sulawesi, and several islands in Nusa Tenggara. The artefacts from this period are Nekara bronze drums discovered throughout Indonesian archipelago, and also ceremonial bronze axe.

Belief system

Early Indonesians were animists who honoured the spirits of nature as well as the ancestral spirits of the dead, as they believed their souls or life force could still help the living. The reverence for ancestral spirits is still widespread among Indonesian native ethnicities; such as among Nias people, Batak, Dayak, Toraja, and Papuans. These reverence among others are evident through the harvest festivals that often invoked the nature spirits and agriculture deities, to the elaborate burial rituals and processions of the deceased elders to preparing and sending them to the realm of ancestors. The prehistoric spirit of ancestors or nature that possess supernatural abilities is identified as hyang in Java and Bali, and still revered in Balinese Hinduism.

Way of life

The human livelihood of prehistoric Indonesia ranges from simple forest hunter-gatherer equipped with stone tools to elaborated agriculture society with grain cultivation, domesticated animals, with weaving and pottery industry.

Ideal agricultural conditions, and the mastering of wet-field rice cultivation as early as the 8th century BCE,[14] allowed villages, towns, and small kingdoms to flourish by the 1st century CE. These kingdoms (little more than collections of villages subservient to petty chieftains) evolved with their own ethnic and tribal religions. Java's hot and even temperature, abundant rain and volcanic soil, was perfect for wet rice cultivation. Such agriculture required a well-organised society in contrast to dry-field rice, which is a much simpler form of cultivation that doesn't require an elaborate social structure to support it.

Buni culture clay pottery was flourished in coastal northern West Java and Banten around 400 BCE to 100 CE [15] Buni culture was probably the predecessor of Tarumanagara kingdom, one of the earliest Hindu kingdom in Indonesia that produces numerous inscriptions, marked the beginning of historical period in Java.

List of sites

Prehistoric relics, such as bones of prehistoric animals and hominids, megalithic monolith such as menhirs, dolmens, statues, burial sites, and paintings in caves cliff niches, include the following:

- Putri cave, Baturaja, South Sumatra

- Pasemah prehistoric site, Lampung

- Caves of Sangkulirang Hill, East Kutai Regency, East Kalimantan

- Cibedug prehistoric site, Banten[16]

- Pangguyangan megalithic sites, Cisolok, Sukabumi Regency, West Java

- Cipari megalithic site, Kuningan, West Java

- Pawon caves, Bandung Regency, West Java

- Gunung Padang Megalithic Site, Cianjur Regency, West Java

- Gunung Padang site, Cilacap Regency, Central Java[17]

- Sangiran valley, Central Java

- Wajak prehistoric sites, Tulungagung Regency, East Java

- Mbolu village prehistoric site, Ngepo village, Tanggunggunung subdistric, Tulungagung Regency, East Java[18]

- Gilimanuk prehistoric site, Jembrana Regency, Bali

- Keramas village prehistoric site, Blahbatuh subdistric, Gianyar regency, Bali[19]

- Leang-leang caves, Maros Regency, South Sulawesi

- Megalithic statues of Lore Lindu National Park, Central Sulawesi

- Liang Bua, Flores, East Nusa Tenggara

- Biak caves prehistoric sites, Biak, Papua (40.000-30.000 SM)[20]

- Beach side prehistoric painting site, Raja Ampat, West Papua

- Tutari megalithic sites, Jayapura, Papua[20]

- Babi caves, Mount Batu Buli, Randu village, Muara Uya, Tabalong, South Kalimantan

See also

Notes

- ↑ epress.anu.edu.au

- ↑ [MacKinnon; Kathy, Alam Asli Indonesia, Penerbit PT Gramedia, Jakarta 1986, page 8]

- ↑ http://www.terradaily.com/reports/Finding_showing_human_ancestor_older_than_previously_thought_offers_new_insights_into_evolution_999.html

- ↑ Pope, G G (1988). "Recent advances in far eastern paleoanthropology". Annual Review of Anthropology. 17 (1): 43–77. doi:10.1146/annurev.an.17.100188.000355.

cited in Whitten, T; Soeriaatmadja, R. E.; Suraya A. A. (1996). The Ecology of Java and Bali. Hong Kong: Periplus Editions Ltd. pp. 309–312.; Pope, G (15 August 1983). "Evidence on the Age of the Asian Hominidae". Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 80 (16): 4988–4992. doi:10.1073/pnas.80.16.4988. PMC 384173

. PMID 6410399.

cited in

Whitten, T; Soeriaatmadja, R. E.; Suraya A. A. (1996). The Ecology of Java and Bali. Hong Kong: Periplus Editions Ltd. p. 309.;

de Vos, J.P.; P.Y. Sondaar (9 December 1994). "Dating hominid sites in Indonesia" (PDF). Science Magazine. 266 (16): 4988–4992. doi:10.1126/science.7992059.

cited in Whitten, T; Soeriaatmadja, R. E.; Suraya A. A. (1996). The Ecology of Java and Bali. Hong Kong: Periplus Editions Ltd. p. 309.

. PMID 6410399.

cited in

Whitten, T; Soeriaatmadja, R. E.; Suraya A. A. (1996). The Ecology of Java and Bali. Hong Kong: Periplus Editions Ltd. p. 309.;

de Vos, J.P.; P.Y. Sondaar (9 December 1994). "Dating hominid sites in Indonesia" (PDF). Science Magazine. 266 (16): 4988–4992. doi:10.1126/science.7992059.

cited in Whitten, T; Soeriaatmadja, R. E.; Suraya A. A. (1996). The Ecology of Java and Bali. Hong Kong: Periplus Editions Ltd. p. 309. - ↑ http://pages.nycep.org/nmg/pdf/Delson_et_al_%20sm3.pdf

- ↑ Brown, P.; Sutikna, T., Morwood, M. J., Soejono, R. P., Jatmiko, Wayhu Saptomo, E. & Rokus Awe Due (27 October 2004). "A new small-bodied hominin from the Late Pleistocene of Flores, Indonesia.". Nature. 431 (7012): 1055–1061. doi:10.1038/nature02999. PMID 15514638. Cite uses deprecated parameter

|coauthors=(help); Morwood, M. J.; Soejono, R. P., Roberts, R. G., Sutikna, T., Turney, C. S. M., Westaway, K. E., Rink, W. J., Zhao, J.- X., van den Bergh, G. D., Rokus Awe Due, Hobbs, D. R., Moore, M. W., Bird, M. I. & Fifield, L. K. (27 October 2004). "Archaeology and age of a new hominin from Flores in eastern Indonesia.". Nature. 431 (7012): 1087–1091. doi:10.1038/nature02956. PMID 15510146. Cite uses deprecated parameter|coauthors=(help) - ↑ http://www.redorbit.com/news/science/1838192/flores_man_could_be_1_million_years_old/

- ↑ Smithsonian (July 2008). "The Great Human Migration": 2.

- ↑ http://www.pasthorizonspr.com/index.php/archives/11/2011/evidence-of-42000-year-old-deep-sea-fishing-revealed

- ↑ Taylor (2003), pages 5–7

- ↑ "Shell tool use by early members of Homo erectus in Sangiran, central Java, Indonesia: cut mark evidence". Journal of Archaeological Science. 34: 48–58. doi:10.1016/j.jas.2006.03.013.

- ↑ |Cipari archaeological park discloses prehistoric life in West Java.

- ↑ |Lore Lindu National Park, Central Sulawesi.

- ↑ Taylor, Jean Gelman. Indonesia. New Haven and London: Yale University Press. pp. 8–9. ISBN 0-300-10518-5.

- ↑ Zahorka, Herwig (2007). The Sunda Kingdoms of West Java, From Tarumanagara to Pakuan Pajajaran with Royal Center of Bogor, Over 1000 Years of Propsperity and Glory. Yayasan cipta Loka Caraka.

- ↑ Ada Lagi Situs Megalitikum, Kali Ini di Cibedug Banten

- ↑ Ada Lagi Mirip "Gunung Padang" di Cilacap

- ↑ Ratusan Fosil Purba Berusia 40.000 SM Ditemukan di Tulungagung

- ↑ Ditemukan Benda Purbakala Sarkofagus & Rangka Manusia Megalitikum di Bali

- 1 2 Papua Kaya Situs Arkeologi Kuno. Kompas daring. Edisi 17 April 2009.

- Moore, MW; Brumm (2007). "Stone artifacts and hominins in island Southeast Asia: New insights from Flores, eastern Indonesia". Journal of Human Evolution. 52 (1): 85–102. doi:10.1016/j.jhevol.2006.08.002.