Rachel Chiesley, Lady Grange

| Rachel Chiesley | |

|---|---|

Portrait of Lady Grange by Sir John Baptiste de Medina c. 1710 | |

| Born | 1679 |

| Died |

12 May 1745 (aged 66) Trumpan, Skye, Inverness-shire, Scotland |

| Known for | Abductee |

| Title | Lady Grange |

| Religion | Church of Scotland |

| Spouse(s) | James Erskine, Lord Grange |

| Children | Charlie, Johnie, James, Mary, Meggie, Fannie, Jeannie, Rachel, John |

| Parent(s) | John Chiesley of Dalry and Margaret Nicholson |

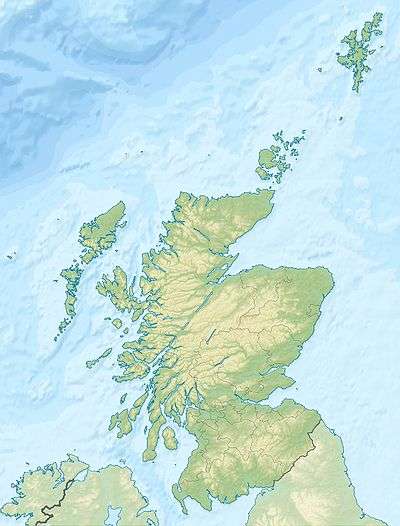

Rachel Chiesley, usually known as Lady Grange (1679–1745), was the wife of Lord Grange, a Scottish lawyer with Jacobite sympathies. After 25 years of marriage and nine children, the Granges separated acrimoniously. When Lady Grange produced letters that she claimed were evidence of his treasonable plottings against the Hanoverian government in London, her husband had her kidnapped in 1732. She was incarcerated in various remote locations on the western seaboard of Scotland, including the Monach Isles, Skye and the distant islands of St Kilda.

Lady Grange's father was convicted of murder and she is known to have had a violent temper; initially her absence seems to have caused little comment. News of her plight eventually reached her home town of Edinburgh however, and an unsuccessful rescue attempt was undertaken by her lawyer, Thomas Hope of Rankeillor. She died in captivity, after being in effect imprisoned for 13 years. Her life has been remembered in poetry, prose and plays.

Early years

Rachel Chiesley was one of ten children born to John Chiesley of Dalry and Margaret Nicholson. The marriage was unhappy and Margaret took her husband to court for aliment. She was awarded 1,700 merks by Sir George Lockhart of Carnwath, the Lord President of the Court of Session. Furious with the result, John Chiesley shot Lockhart dead on the High Street of Edinburgh as he walked home from church on Easter Sunday, 31 March 1689.[1] The assailant made no attempt to escape and confessed at his trial, held before the Lord Provost the next day. Two days later he was taken from the Tolbooth to the Mercat Cross on the High Street. His right hand was cut off before he was hanged, and the pistol he had used for the murder was placed round his neck.[2] Rachel Chiesley's birthday is unknown but she was baptised on 4 February 1679 and was probably born shortly before then, making her about ten years old at the time of her father's execution.[3]

Marriage and children

The date of Chiesley's marriage to James Erskine is uncertain: based on the text of a letter she wrote much later in life, it may have been in 1707 when she was about 28.[Note 1] Erskine was the younger son of Charles Erskine, Earl of Mar and in 1689 his older brother John Erskine, became Earl of Mar on their father's death.[7][Note 2] These were politically troubled times; the Jacobite cause was still popular in many parts of Scotland, and the younger Earl was nicknamed "Bobbing John" for his varied manoeuverings.[10] After playing a prominent role in the Jacobite rebellion of 1715 he was stripped of his title, sent into exile, and never returned to Scotland.[9]

The young Lady Grange has been described as a "wild beauty", and it is likely the marriage only took place after she became pregnant.[11][Note 3] This uncertain background notwithstanding, Lord and Lady Grange led a superficially uneventful domestic life. They divided their time between a town house at the foot of Niddry's Wynd off the High Street in Edinburgh and an estate at Preston (near Prestonpans in East Lothian), where Lady Grange was the factor (or supervisor) for a time.[13][14] Her husband was a successful lawyer, becoming Lord Justice Clerk in 1710,[15] and the marriage produced nine children:

- Charlie, born August 1709.[12]

- Johnie, born March 1711, died age two months.[12]

- James, born March 1713.[12] He married his uncle "Bobbing" John's daughter Frances. Their son John eventually became Earl of Mar after the title was restored.[16][17]

- Mary, born July 1714,[12] who married John Keith the 3rd Earl of Kintore in August 1729.[17][18]

- Meggie, who died young in May 1717.[19]

- Fannie, born December 1716.[12]

- Jeannie, born in December 1717.[19]

- Rachel.[12]

- John.[12]

In addition, Lady Grange miscarried twice and one of the above children is known to have died in 1721.[12]

Acrimony and separation

There was evidently an element of discord in the marriage that eventually became public knowledge. In late 1717 or early 1718, Erskine received warnings from a friend that he had enemies in the government. At about the same time one of the children's tutors recorded in his diary that Lady Grange was "imperious with an unreasonable temper".[20] Her outbursts were evidently also capable of frightening her younger daughters and after Lady Grange's kidnapping, no action was ever taken on her behalf by any of her children, the eldest of whom would have been in their early twenties when she was abducted. Macaulay writes that "[t]he calm acceptance by the family of their mother's disappearance would persuade many that it need not be a matter of concern to them either".[21][Note 4] This restraint may have been influenced by the fact their mother had previously disinherited all of them when the youngest were still infants, an outcome described as "unnatural" by the Sobieski Stuarts,[21][22] two English brothers who claimed descent from Prince Charles Edward Stuart.[Note 5]

As the Erskines' marriage trouble increased, Lady Grange's behaviour became increasingly unpredictable. In 1730, the factorship of the Preston estate was removed from her, further increasing her angst. Her discovery of an affair her husband was conducting with coffeehouse owner Fanny Lindsay can only have made matters worse. In April of that year, she threatened suicide and to run naked through the streets of Edinburgh. She may have kept a razor under her pillow and attempted to intimidate her husband by reminding him whose daughter she was. On 27 July, she signed a formal letter of separation from James Erskine but things did not improve.[24] For example, she barracked her husband in the street and in church and he and one of their children were forced to hide from her in a tavern for two hours or more on one occasion. She intercepted one of his letters and took it to the authorities alleging it was evidence of treason. She is also said to have stood outside the house in Niddry's Wynd, waving the letter and shouting obscenities on at least two occasions. In January 1732 she booked a stagecoach to London and James Erskine and his friends, afraid her presence there would cause them further trouble, decided it was time to take decisive action.[25]

Kidnap

Lady Grange was abducted from her home on the night of 22 January 1732 by two Highland noblemen, Roderick MacLeod of Berneray and Macdonald of Morar, and several of their men. After a bloody struggle, she was taken out of the city in a sedan chair and then on horseback to Wester Polmaise near Falkirk, where she was held until 15 August on the ground floor of an uninhabited tower.[26] She was by then over fifty years old.

Upon the 22d of Jan 1732, I lodged in Margaret M'Lean house and a little before twelve at night Mrs M'Lean being on the plot opened the door and there rush'd in to my room some servants of Lovats and his Couson Roderick Macleod he is a writer to the Signet they threw me down upon the floor in a Barbarous manner I cri'd murther murther then they stopp'd my mouth I puled out the cloth and told Rod: Macleod I knew him their hard rude hands bleed and abassed my face all below my eyes they dung out some of my teeth and toere the cloth of my head and toere out some of my hair I wrestled and defend'd -my self with my hands then Rod: order'd to tye down my hands and cover my face most pity- fully there was no skin left on my face with a cloath and stopp'd my mouth again they had wrestl'd so long with me that it was al that I could breath, then they carry'd me down stairs as a corps.[27]

Letter written by Lady Grange on St Kilda, 1738

From there she was taken west by Peter Fraser (a page of Lord Lovat) and his men through Perthshire. At Balquhidder, according to MacGregor tradition, she was entertained in the great hall, provided with a meal of venison, and slept on a heather bed covered with deerskins.[28] The existence of St Fillan's Pool on the River Fillan near Tyndrum would have provided useful cover for her captors: it was regularly used as a cure for insanity, which would have helped to explain her presence to the curious.[29] The details of the onward route from there are not clear but it is likely she was taken through Glen Coe to Loch Ness and then through Glen Garry to Loch Hourn on the west coast. After a short delay she was then put on board ship to the Monach Isles. The difficulty of her position must have quickly become evident. She was in the company of men whose loyalty was to clan chieftains rather than the law, and few of them spoke any English at all. Their native Gaelic would have been incomprehensible to her, although as her years of captivity wore on she slowly learned something of the language.[30] She complained that young members of the local aristocracy visited her as she waited by the shores of Loch Hourn, but that "they came with design to see me, but not to relieve me".[31]

Monach Isles

The Monach Isles, also known as Heisker, lie 8 kilometres (5 mi) west of North Uist in the Outer Hebrides, an archipelago itself lying off the western coast of Scotland. The main islands are Ceann Ear, Ceann Iar and Shivinish, which are all linked at low tide and have a combined area of 357 hectares (880 acres). The islands are low-lying and fertile, and their population in the 18th century may have been about 100.[32][Note 6] At the time they were owned by Sir Alexander MacDonald of Sleat, and Lady Grange was housed with his tacksman, another Alexander MacDonald, and his wife. When she complained about her condition, she was told by her host that he had no orders to provide her with either clothes, or food other than the normal fare he and his wife were used to. She lived in isolation for two years, not even being told the name of the island where she was living, and it took her some time to find out who her landlord was. She was there until June 1734, when John and Norman MacLeod from North Uist arrived to move her on. They told her they were taking her to Orkney, but instead set sail for the Atlantic outliers of St Kilda.[32][33]

St Kilda

One of the more poignant ruins on the island of Hirta in the St Kilda archipelago is the site of Lady Grange's House.[34] The "house" is in fact a large cleit or stone storage hut in the Village meadows that is said to resemble "a giant Christmas pudding".[35] Some authorities believe it was rebuilt on the site of a larger blackhouse where she lived during her incarceration,[36] although in 1838 the grandson of a St Kildan who had assisted her quoted the dimensions as being "20 feet by 10 feet" (7 metres by 3 metres), which is roughly the size of the cleit.[35][Note 7]

Hirta is more remote than the Monach Isles, lying 66 kilometres (41 mi) west-northwest of Benbecula in the North Atlantic Ocean[39] and the predominant theme of life on St Kilda was isolation. When Martin Martin visited the islands in 1697,[40] the only means of making the journey was by open longboat, which could take several days and nights of rowing and sailing across the open ocean and was next to impossible in autumn and winter. In all seasons, waves up to 12 metres (40 ft) high lash the beach of Village Bay, and even on calmer days landing on the slippery rocks can be hazardous. Cut off by distance and weather, the natives knew little of the rest of the world.[41]

Lady Grange's circumstances were correspondingly more uncomfortable and no-one on the island spoke any English.[38] She described Hirta as "a viled neasty, stinking poor Isle" and insisted that "I was in great miserie in the Husker but I'm ten times worse and worse here".[27] Her lodgings were very primitive. They had an earthen floor, rain ran down the walls and in winter snow had to be scooped out in handfuls from behind the bed.[42] She spent her days asleep, drank as much whisky as was available to her, and wandered the shore at night bemoaning her fate. During her sojourn on Hirta she wrote two letters relating her story, which eventually reached Edinburgh. One, dated 20 January 1738, found its way to Thomas Hope of Rankeillor, her lawyer, in December 1740. Some sources state that the first letter had been hidden in some yarn that was collected as part of a rent payment and taken to Inverness and thence to Edinburgh.[43] The idea of the letter's concealment in yarn is also mentioned by James Boswell in his Journal of a Tour to the Hebrides (1785). However, Macaulay states that this method for the delivery of the letter(s) has "no basis in reality" and that both letters were smuggled off Hirta by Roderick MacLennan, the island's minister.[44] Whatever its route, the letter caused a sensation in Edinburgh although James Erskine's friends managed to block attempts by Hope to obtain a warrant to search St Kilda.[Note 8]

In the second letter, addressed to Dr Carlyle, minister of Inveresk, Lady Grange writes bitterly of the roles of Lord Lovat and Roderick MacLeod in her capture and bemoans being described by Sir Alexander MacDonald as "the cargo".[27][47][Note 9] Hope had known of Lady Grange's removal from Edinburgh but had assumed she would be well cared for. Appalled by her condition, he paid for a sloop with twenty armed men on board to go to St Kilda at his own expense. It had already set sail by 14 February 1741, but it arrived too late.[43][48] Lady Grange had been removed from the island, probably in the summer of 1740.[49]

After the Battle of Culloden in 1746, it was rumoured that Prince Charles Edward Stuart and some of his senior Jacobite aides had escaped to St Kilda. An expedition was launched, and in due course British soldiers were ferried ashore to Hirta. They found a deserted village, as the St Kildans, fearing pirates, had fled to caves to the west. When they were persuaded to come down, the soldiers discovered that the isolated natives knew nothing of the Prince and had never heard of King George II either.[50] Paradoxically, Lady Grange's letters and her resultant evacuation from the island may have prevented her being found by this expedition.[Note 10]

Skye

By 1740 Lady Grange was 61 years old. Removed from St Kilda in haste, she was transported to various locations in the Gàidhealtachd including possibly Assynt in the far north west of mainland Scotland and the Outer Hebridean locations of Harris and Uist before arriving at Waternish on Skye in 1742.[Note 11] Local folklore suggests she may have been kept for 18 months in a cave either at Idrigill on the Trotternish peninsula[53] or on the Duirinish coast near the stacks known as a "Macleod's Maidens".[54] She was certainly later housed with Rory MacNeil at Trumpan in Waternish. She died there on 12 May 1745, and MacNeil had her "decently interred" the following week in the local churchyard. For reasons unknown a second funeral was held at nearby Duirinish some time thereafter, where a large crowd gathered to watch the burial of a coffin filled with turf and stones.[55]

It is sometimes stated that this was her third funeral, Lord Grange having conducted one in Edinburgh shortly after her kidnapping.[56][57] However, this story first appears in writing in 1845 and no other evidence of its veracity has emerged.[52][58]

Motivations

Lady Grange's story is a remarkable one[Note 12] and various issues have been raised by Macaulay (2009) as requiring explanation. These include: what drove James Erskine to these extraordinary lengths?;[60] why were so many individuals willing to participate in this illegal and dangerous kidnapping of his wife?;[61] and how was she held for so long without rescue?[60]

The first and second of these issues are related. Erskine's brother had already been exiled for his support of the Jacobites. Simon Fraser, Lord Lovat, a key figure in Lady Grange's abduction was himself executed for his part in the Jacobite Rising of 1745.[62] No concrete evidence of Erskine's plotting against the crown or government has ever emerged, but any threat of such exposure, whether based in fact or fantasy would certainly have been taken very seriously by all concerned. It was thus relatively easy for Erskine to find accomplices amongst the Highland gentry. In addition to Simon Fraser and Alexander Macdonald of Sleat, the Sobieski Stuarts listed Norman MacLeod of Dunvegan[63]—who became known as "The Wicked Man"[64]—as the senior accomplices.[65] Erskine himself was a "singular compound of good and bad qualities".[66] In addition to his legal career he was elected to Parliament in 1734 and he survived the vicissitudes of the Jacobite rebellions unscathed.[15] He was a philanderer and over-partial to claret, whilst at the same time deeply religious.[67] This last quality would have been instrumental in any decision not to have his wife assassinated,[68] and he did not marry his long-term partner Fanny Lindsay until after he had heard of the first Lady Grange's death.[69]

The reason no successful rescue was ever effected lies in the remoteness of the Hebrides from the anglophone world in the early 18th century. No reliable naval charts of the area became available until 1776.[Note 13] Without local assistance and knowledge, finding a captive in this wilderness would have required a significant expeditionary force. Nonetheless, the lack of action taken by Edinburgh society in general and her children in particular to retrieve one of their own is remarkable. The Kirk hierarchy, for example, made no attempt to contact her or convey news of her condition to the capital, yet they could easily have done so. Whatever the call of morality and natural justice may have suggested, John Chiesley's daughter evidently did not command a sympathetic audience in her home town.[71]

In her account of the affair, Margaret Macaulay explores 18th-century attitudes to women in general as a significant factor[72] and notes that although numerous documents from the hands of Lord Grange's friends and supporters are still extant, not a single contemporary female view of the affair has survived, save that of Lady Grange herself.[73] Divorces were complex and divorced mothers were rarely given custody of children.[74][Note 14] Furthermore, Lord Grange's powerful friends in both the church and the legal profession might have made this a risky endeavour.[75] Something of James Erskine's attitude to these matters may perhaps be gleaned from the fact that for his first speech in the House of Commons he chose to oppose the repeal of various laws relating to witchcraft. Even in his day this appeared unduly conservative and his perorations were met with laughter, which effectively ended his political career before it had begun.[76] Writing in the mid-19th century the Sobieski Stuarts told the tale from the perspective of the descendants of the Highland aristocrats who had been responsible for Chiesley's kidnap and imprisonment. They emphasise Lady Grange's personal shortcomings, although to modern sensibilities these hardly seem good reasons for a judge and Member of Parliament and his wealthy friends to organise an illegal kidnapping and life sentence.[77]

As for Lady Grange herself, her vituperative outbursts and indulgence in alcohol were clearly important factors in her undoing.[78] Alexander Carlyle described her as "stormy and outrageous", whilst noting that it was in her husband's interests to exaggerate the nature of her violent emotions.[78] Macaulay (2009) takes the view that the ultimate cause of her troubles was her reaction to her husband's infidelity. In an attempt to end his relationship with Mrs Lindsay, (who owned a coffee house in Haymarket, Edinburgh), Rachel threatened to expose him as a Jacobite sympathiser. Perhaps she did not understand the magnitude of this accusation and the danger it posed to her husband and his friends, or how ruthless their instincts of self-preservation were likely to be.[79][80]

In literature and the arts

Rachel Chiesley's tale inspired a romantic poem called "Epistle from Lady Grange to Edward D— Esq" written by William Erskine in 1798[Note 15] and a 1905 novel entitled The Lady of Hirta, a Tale of the Isles by W. C. Mackenzie. Edwin Morgan also published a sonnet in 1984 called "Lady Grange on St Kilda".[83][84] The Straw Chair is a two-act play by Sue Glover, also about the time on St Kilda, first performed in Edinburgh in 1988.[85] Burdalane is a play about these same events by Judith Adams performed in 1996 at the Battersea Arts Centre, London and on BBC Radio 4.[86]

Boswell and Johnson discussed the subject in their 1773 tour of the Hebrides. Boswell wrote: "After dinner to-day, we talked of the extraordinary fact of Lady Grange's being sent to St Kilda, and confined there for several years, without any means of relief. Dr Johnson said, if M'Leod would let it be known that he had such a place for naughty ladies, he might make it a very profitable island."[Note 16]

There are portraits of both James Erskine and Rachel Chiesley in the Scottish National Portrait Gallery in Edinburgh, by William Aikman and Sir John Baptiste de Medina respectively. When the writer Margaret Macaulay sought them out she discovered they had been placed together in the same cold store.[3]

See also

- Queen Joanna of Castile, 16th century monarch who was declared mentally ill and confined, possibly because those around her (such as her father, Ferdinand of Aragon) wished to control her kingdom.

- Lisbeth Salander, a 21st-century fictional heroine who is declared mentally incompetent by authority figures trying to control her behaviour.

- Tibbie Tamson, an 18th-century Scots woman, whose persecution may have led to her suicide.

Footnotes

- ↑ In a letter written from St Kilda, Lady Grange states that "He told me he loved me two years or he gott me and we lived 25 years together few or non I thought so happy."[6] If her recollection is accurate, 25 years before her kidnapping would give a date of 1707.

- ↑ The Mar lineage is very old and the numbering of the titles arrived at by more than one system. John Erskine is variously described as the 6th, 11th and 22nd Earl.[8][9]

- ↑ This pregnancy and another in 1708 ended in miscarriage.[12]

- ↑ Macaulay also poignantly notes that "no hue and cry was ever raised on behalf of Lady Grange by the daughter [Mary] she had called her angel".[21]

- ↑ Although taken seriously by Lord Lovat, the Sobieski Stuarts' claims were eventually exposed and the Collins Encyclopaedia of Scotland states that their publication on the history of clan tartans, Vestiarium Scoticum "is as bogus as its author's descent".[23]

- ↑ The islands were abandoned in 1810 because of overgrazing, but re-settled in 1839. In common with many of the more remote Scottish islands they were then abandoned once more in the mid-20th century. Only lighthouse keepers lived there from the early 1930s until 1942, when they too left.[32]

- ↑ According to the National Trust for Scotland the cleit is "traditionally said to be the house where she was held prisoner, but this is unlikely to be true".[37] Quine (2000) states that it is the "possible site" of the house where Lady Grange lived, but that the house itself was destroyed prior to 1876.[34] Maclean (1977) refers to the structure as a "two roomed cottage".[38] Fleming (2005) notes the various suggestions on record about the site of the dwelling but concludes that "there is no reason to believe there was any break in the islander's oral traditions in the period since the 1730s".[35]

- ↑ In 1732 Lord Lovat had written "But as to that insolent fellow Mr Hope of Eankiller, I would advise him to to [not to] meddle with me, for the moment that I can prove that he attacts my character and reputation by any calumnie I'l certainly pursue him for Scandalum Magnatum".[27] Hope was well able to take care of himself and is fondly remembered in Edinburgh as the creator of The Meadows which was also known for some time as "Hope Park".[45] MacLennan was not so lucky. Ostracised in Edinburgh as a result of evidence produced against him and his wife by Lord Grange's legal counsel,[46] he eventually died in poverty on the island of Stroma, circa 1757.[45]

- ↑ No original survives of the second letter, and a copy published in 1819 is dated 1741, which makes little sense as it relates to her time on St Kilda. This may have been the date it was copied.[27]

- ↑ Although she died in May 1745 the year before this expedition, her further travails and movements after she left St Kilda may have hastened her demise.[51]

- ↑ According to a 19th-century source, she learned to spin there, in a repetition of the story relating to St Kilda, managed to smuggle a letter out in a ball of yarn, which then had the result of a government naval vessel being sent out to look for her, although there is no surviving evidence for any of these assertions. The source is Clerk (1845) and Macaulay (2009) states that no letter referring to her life on Skye has ever been found, there is no record of any such sailing by a government vessel and that "nor indeed does learning to spin sound quite like Lady Grange's style."[52]

- ↑ Boswell (1785) wrote: "The true story of this lady, which happened In this century, is as frightfully romantick as if it had been the fiction of a gloomy fancy."[59]

- ↑ The failure of the British navy to capture Bonnie Prince Charlie after the Battle of Culloden in 1746 was a major factor in the creation of a new rutter by Murdoch Mackenzie, Hydrographer to the Admiralty, called A Nautical Description researched from 1748 to 1757 and published in 1776. Johan Blaeu's 1654 map was the best chart of the area at the time, but even this was not available to the Hanoverian government and military at the time.[70]

- ↑ The Scottish legal system of the day was "fundamentally different"[74] from its English equivalent in these matters. For example, Lady Grange could have sued for divorce in Scotland as husbands and wives were treated alike in this matter, although in England at the time "adultery by the husband was generally regarded as a regrettable but understandable foible".[74]

- ↑ Erskine (c. 1769–1822), later Lord Kinneder, was a judge with an interest in literature and a mentor to Walter Scott. According to David Douglas he "became the nearest and most confidential of all [Scott's] Edinburgh associates."[81] His father was the Rev. William Erskine, Episcopalian minister of Muthill in Perthshire from 1732–1783, who was born in 1709.[82] It has not been possible to establish whether or not he was related to Rachel Chiesley.

- ↑ In an additional note Boswell added: "She was the wife of one of the Lords of Session in Scotland, a man of the very first blood of his country. For some mysterious reasons, which have never been discovered, she was seized and carried off in the dark, she knew not by whom, and by nightly journies was conveyed to the Highland shores, from whence she was transported by sea to the remote rock of St Kilda, where she remained, amongst its few wild inhabitants, a forlorn prisoner, but had a constant supply of provisions, and a woman to wait on her. No inquiry was made after her, till she at last found means to convey a letter to a confidential friend, by the daughter of a Catechist who concealed it in a clue of yarn. Information being thus obtained at Edinburgh, a ship was sent to bring her off; but intelligence of this being received, she was conveyed to M'Leod's island of Herries, where she died."[59]

References

Citations

- ↑ Macaulay (2009) pp. 23–24

- ↑ Macaulay (2009) pp. 29–30

- 1 2 Macaulay (2009) p. 19

- ↑ "Gladstone's Land". National Trust for Scotland. Retrieved 8 August 2010.

- ↑ "Gladstone's Land". VisitScotland. Retrieved 4 February 2012.

- ↑ Macaulay (2009) p. 33

- ↑ "Mormaers of Mar and Earls of Mar". Tribe of Mar. Retrieved 5 February 2012.

- ↑ Ehrenstein, Christoph von (2004) "John Erskine". Oxford Dictionary of National Biography. Retrieved 5 February 2012.

- 1 2 Bruce, Maurice (1937) "The Duke of Mar in Exile, 1716–32". Transactions of the Royal Historical Society. 4th Series, 20 pp. 61–82. JSTOR. Retrieved 8 May 2010.

- ↑ Keay & Keay (1994) p. 359

- ↑ "Uncovered: the lost manor of Lady Grange, Scotland's 18th century it girl". Archaeology Daily News. Retrieved 8 May 2010.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 Macaulay (2009) p. 169

- ↑ Maclean (1977) p. 83

- ↑ Macaulay (2009) pp. 34, 42

- 1 2 Brunton (1832) p. 484

- ↑ Gibbs, Vicary; Doubleday, H. A.; Howard de Walden, Lord (eds) (1932) The Complete Peerage VIII London: St Catherine Press pp. 425–27

- 1 2 Mosley, Charles (ed) (2003) Burke's Peerage, Baronetage and Knightage: 107th edition II Wilmington, Delaware: Burke's Peerage & Gentry ISBN 978-0-9711966-2-9 pp. 2604, 2608–10

- ↑ "Kintore, Earl of (S, 1677)". Cracroft's Peerage. Retrieved 5 February 2012.

- 1 2 Macaulay (2009) p. 36

- ↑ Extract from James Erksine's diary recorded by James Maidment in 1843, quoted by Macaulay (2009) p. 37

- 1 2 3 Macaulay (2009) p. 41

- ↑ Macaulay (2009) p. 161

- ↑ Keay & Keay (1994) p. 889

- ↑ Macaulay (2009) pp. 33, 41, 45, 47, 49

- ↑ Macaulay (2009) pp. 54–55, 57, 64

- ↑ Macaulay (2009) pp. 65–70

- 1 2 3 4 5 Laing (1874)

- ↑ Macaulay (2009) pp. 73, 77

- ↑ Macaulay (2009) p. 78

- ↑ Macaulay (2009) pp. 78–83

- ↑ Macaulay (2009) p. 83

- 1 2 3 Haswell-Smith (2004) pp. 254–56

- ↑ Macaulay (2009) pp. 84–86

- 1 2 Quine (2000) p. 48

- 1 2 3 Fleming (2005) p. 135

- ↑ "St Kilda, Hirta, Village Bay, Cleit 85". Canmore. Retrieved 8 May 2010.

- ↑ "St Kilda: Fascinating Facts". National Trust for Scotland. Retrieved 19 August 2007.

- 1 2 Maclean (1977) p. 84

- ↑ "St Kilda". National Trust for Scotland. Retrieved 8 May 2010.

- ↑ Martin, Martin (1703)

- ↑ Steel (1988) pp. 28–30

- ↑ Macaulay (2009) p. 130

- 1 2 Maclean (1977) p. 85

- ↑ Macaulay (2009) p. 119

- 1 2 Macaulay (2009) pp. 162–63

- ↑ Macaulay (2009) p. 131

- ↑ Macaulay (2009) p. 122

- ↑ Macaulay (2009) pp. 123–25

- ↑ Macaulay (2009) p. 127

- ↑ Steel (1988) p. 32

- ↑ Macaulay (2009) p. 144

- 1 2 Macaulay (2009) p. 142

- ↑ Macaulay (2009) p. 143

- ↑ Macleod (1906) p. 24

- ↑ Macaulay (2009) pp. 146, 149

- ↑ Keay & Keay (1994) p. 358

- ↑ Steel (1988) p. 31

- ↑ Clerk (1845)

- 1 2 Boswell (1785) "Sunday 19th September"

- 1 2 Macaulay (2009) p. 18

- ↑ Macaulay (2009) p. 17

- ↑ Furgol, Edward M. (2004) "Simon Fraser". Oxford Dictionary of National Biography. Retrieved 5 February 2012.

- ↑ Stiùbhart, Domhnall Uilleam (2004) "Norman MacLeod of Dunvegan". Oxford Dictionary of National Biography. Retrieved 5 February 2012.

- ↑ Mackenzie, Alexander (1887) The Celtic Magazine 12 Inverness: A. & W. Mackenzie pp. 119–22

- ↑ Macaulay (2009) p. 89

- ↑ Macaulay (2009) p. 155, possibly quoting the antiquarian David Laing.

- ↑ Macaulay (2009) pp. 135–36, 139

- ↑ Macaulay (2009) p. 90

- ↑ Proceedings of the Society (11 June 1877)

- 1 2 Bray (1996) pp. 58–59

- ↑ Macaulay (2009) pp. 117–18

- ↑ Macaulay (2009) pp. 170–71

- ↑ Macaulay (2009) pp. 153–54

- 1 2 3 Macaulay (2009) p. 170

- ↑ Macaulay (2009) p. 171

- ↑ Macaulay (2009) p. 135

- ↑ Sobieski Stuart (1847)

- 1 2 Macaulay (2009) p. 154

- ↑ Macaulay (2009) p. 137

- ↑ Macaulay (2009) pp. 156–57

- ↑ Scott (1771–1832) note 91

- ↑ "The Private Lives of Books: Handlist of Exhibits". (2004) (pdf) National Library of Scotland. p. 24

- ↑ Groote, Guusje. "On 'Lady Grange on St Kilda' ". edwinmorgan.com. Retrieved 7 May 2010.

- ↑ "Edwin Morgan". BBC. Retrieved 7 May 2010.

- ↑ Macaulay (2009) pp. 173–74

- ↑ "Reviews". Judith Adams. Retrieved 9 May 2013.

General references

- Boswell, James (1785) Journal of a Tour to the Hebrides with Samuel Johnson, LL.D.. Adelaide University. Retrieved 1 May 2010.

- Bray, Elizabeth (1996) The Discovery of the Hebrides: Voyages to the Western Isles 1745–1883. Edinburgh: Birlinn. ISBN 978-1-874744-59-7.

- Brunton, George (1832) An Historical Account of the Senators of the College of Justice, from its Institution in 1532. London: Saunders and Benning.

- Clerk, Rev. Archibald (1845) "Parish of Duirinish, Skye". New Statistical Account of Scotland. Edinburgh and London.

- Fleming, Andrew (2005) St. Kilda and the Wider World: Tales of an Iconic Island. Bollington, Cheshire: Windgather Press. ISBN 978-1-905119-00-4.

- Haswell-Smith, Hamish (2004) The Scottish Islands. Edinburgh: Canongate. ISBN 978-1-84195-454-7.

- Keay, J., and Keay, J. (1994) Collins Encyclopaedia of Scotland. London: HarperCollins. ISBN 978-0-00-255082-6.

- Laing, David (1874) "An episode in the life of Mrs. Rachel Erskine, Lady Grange, detailed by herself in a letter from St. Kilda, January 20, 1738, and other original papers". Proceedings of the Society of Antiquaries of Scotland. xi Edinburgh. pp. 593–608.

- Macaulay, Margaret (2009) The Prisoner of St Kilda: The true story of the unfortunate Lady Grange. Edinburgh: Luath. ISBN 978-1-906817-02-2.

- Macleod, Rev. R. C. (1906) "The Macleods: A Short Sketch Of Their Clan, History, Folk-Lore, Tales, And Biographical Notices Of Some Eminent Clansmen". Edinburgh: Clan MacLeod Society. Retrieved 22 August 2010.

- Martin, Martin (1703) "A Voyage to St. Kilda" in A Description of The Western Islands of Scotland. Appin Regiment/Appin Historical Society. Retrieved 3 March 2007.

- Maclean, Charles (1977) Island on the Edge of the World: the Story of St. Kilda. Edinburgh: Canongate. ISBN 978-0-903937-41-2.

- Proceedings of the Society (11 June 1877) "Lady Grange in Edinburgh 1730". Proceedings of the Society of Antiquaries of Scotland. Edinburgh.

- Quine, David (2000) St Kilda. Grantown-on-Spey: Colin Baxter Island Guides. ISBN 978-1-84107-008-7.

- Scott, Sir Walter (1771–1832) The Journal of Sir Walter Scott From the Original Manuscript at Abbotsford. Project Gutenberg. Retrieved 14 August 2010.

- Sobieski Stuart, John and Charles Edward (1847) Tales of the Century: or Sketches of the romance of history between the years 1746 and 1846. Edinburgh.

- Steel, Tom (1988) The Life and Death of St. Kilda. London: Fontana. ISBN 978-0-00-637340-7.

External links

- Canmore Royal Commission on the Ancient and Historical Monuments of Scotland, Lady Grange's "house" on St Kilda