Reynard

Reynard (Dutch: Reinaert; French: Renart; German: Reineke; Latin: Renartus) is the main character in a literary cycle of allegorical Dutch, English, French and German fables. Those stories are largely concerned with Reynard, an anthropomorphic red fox and trickster figure. His adventures usually involve him deceiving other anthropomorphic animals for his own advantage or trying to avoid retaliations from them. His main enemy and victim across the cycle is his uncle, the wolf Isengrim (or Ysengrim). While the character of Reynard appears in later works, the core stories were written during the Middle Ages by multiple authors and are often seen as parodies of medieval literature such as courtly love stories and chansons de geste, as well as a satire of political and religious institutions.[1]

Etymology of the name

Theories about the origin of the name Reynard are:

- from the Germanic man's name Reginhard, which came from 'regin' = "the divine powers of the old Germanic religion" and "hard": "made hard by the gods", but with the disuse of the old Germanic religion was later likely interpreted as "rain-hard" meaning "staying steady under a rain of blows from weapons in battle" or similar.

- from the Germanic man's name Reginhard (later condensed to Reinhard), which comes from 'regin' = "counsel" and 'harti' = "strong", denoting someone who is wise, clever, or resourceful.

Because of the popularity of the Reynard stories, renard became the standard French word for "fox", replacing the old French word for "fox", which was goupil from Latin vulpecula. Goupil is now dialectal or archaic.

In medieval European folklore and literature

_detail.jpg)

The figure of Reynard is thought to have originated in Lorraine folklore from where it spread to France, the Low Countries, and Germany.[2] An extensive treatment of the character is the Old French Le Roman de Renart written by Pierre de Saint-Cloud around 1170, which sets the typical setting. Reynard has been summoned to the court of king Noble, or Leo, the lion, to answer charges brought against him by Isengrim the wolf. Other anthropomorphic animals, including Bruin the bear, Baldwin the ass, and Tibert (Tybalt) the cat, all attempt one stratagem or another. The stories typically involve satire whose usual butts are the aristocracy and the clergy, making Reynard a peasant-hero character.[2] The story of the preaching fox found in the Reynard literature was used in church art by the Catholic Church as propaganda against the Lollards.[3] Reynard's principal castle, Maupertuis, is available to him whenever he needs to hide away from his enemies. Some of the tales feature Reynard's funeral, where his enemies gather to deliver maudlin elegies full of insincere piety, and which feature Reynard's posthumous revenge. Reynard's wife Hermeline appears in the stories, but plays little active role, although in some versions she remarries when Reynard is thought dead, thereby becoming one of the people he plans revenge upon. Isengrim (alternate French spelling: Ysengrin) is Reynard's most frequent antagonist and foil, and generally ends up outwitted, though he occasionally gets revenge.

Ysengrimus

Reynard appears first in the medieval Latin poem Ysengrimus, a long Latin mock-epic written c. 1148-1153 by the poet Nivardus in Ghent, that collects a great store of Reynard's adventures. He also puts in an early appearance in a number of Latin sequences by the preacher Odo of Cheriton. Both of these early sources seem to draw on a pre-existing store of popular culture featuring the character.

Roman de Renart

The first "branch" (or chapter) of the Roman de Renart appears in 1174, written by Pierre de St. Cloud, although in all French editions it is designated as "Branch II". The same author wrote a sequel in 1179—called "Branch I"—but from that date onwards, many other French authors composed their own adventures for Renart li goupil ("the fox"). There is also the text Reinhard Fuchs by Heinrich der Glïchezäre, dated to c.1180.

Pierre de St. Cloud opens his work on the fox by situating it within the larger tradition of epic poetry, the fabliaux and Arthurian romance:

| This would roughly translate as: | |

|

Seigneurs, oï avez maint conte |

Lords, you have heard many tales, |

Van den vos Reynaerde

A mid 13th-century Middle Dutch version of the story by Willem die Madoc maecte (Van den vos Reynaerde, Of Reynaert the Fox), is also made up of rhymed verses (the same AA BB scheme). Like Pierre, very little is known of the author, other than the description by the copyist in the first sentences:[4]

| Middle Dutch | English |

|

Willem, die Madocke maecte, |

Willem who made Madocke, |

Madocke or Madoc is thought to be another one of Willem's works that at one point existed but was lost. The Arnout mentioned was an earlier Reynard poet whose work Willem (the writer) alleges to have finished. However, there are serious objections to this notion of joint authorship, and the only thing deemed likely is that Arnout was French-speaking ("Walschen" in Middle Dutch referred to northern French-speaking people, specifically the Walloons).[5] Willem's work became one of the standard versions of the legend, and was the foundation for most later adaptations in Dutch, German, and English, including those of William Caxton, Goethe, and F. S. Ellis.[4]

Chaucer

Geoffrey Chaucer used Reynard material in the Canterbury Tales; in "The Nun's Priest's Tale", Reynard appears as "Rossel" and an ass as "Brunel". In 1481 William Caxton printed The Historie of Reynart the Foxe, which was translated from a Middle Dutch version of the fables.[2] Also in the 1480s, the Scottish poet Robert Henryson devised a highly sophisticated development of Reynardian material as part of his Morall Fabillis in the sections known as The Talking of the Tod. Hans van Ghetelen, a printer of Incunabula in Lübeck printed an early German version called Reinke de Vos in 1498. It was translated to Latin and other languages, which made the tale popular across Europe. Reynard is also referenced in the Middle English poem Sir Gawain and the Green Knight during the third hunt.

Modern treatment

Renert

Renert [full original title: Renert oder de Fuuß am Frack an a Ma’nsgrëßt],[6][7] was published in 1872 by Michel Rodange, a Luxembourgeois author.

An epic satirical work—adapted from the 1858 Cotta Edition of Goethe's fox epic Reineke Fuchs to a setting in Luxembourg—[6] it is known for its insightful analysis of the unique characteristics of the people of Luxembourg, using regional and sub-regional dialects to depict the fox and his companions.

Antisemitic version

Van den vos Reynaerde (Of Reynaert the Fox) was an anti-Semitic children's story, written by the Dutch-Belgian Robert van Genechten, and named after the medieval Dutch poem. It was first published in 1937 in Nieuw-Nederland, a monthly publication of the Dutch Nazi Party's front, the NSB. In 1941 it was published as a book.

The story features a rhinoceros called Jodocus, somewhat akin to the Dutch word jood; and a donkey, Boudewijn, who occupies the throne. Boudewijn, as King of "Belgium", was the Dutch name for the contemporary real-world Belgian crown prince. In the story, Jodocus is an outsider who comes to the Empire and subsequently introduces new ideas that drastically alter the natural order. The land is then declared a "Republic", where "liberty, equality and fraternity" are to be exercised. This dystopian view of socialist republics fits the Nazi ideology on equality and liberty as something degenerate: "There was no one who kept to the rules of the race. Rabbits crept into foxholes, the chickens wanted to build an eyrie." Eventually, Reynard and the others trick and kill Jodocus and his colleagues.[8]

Van den vos Reynaerde was also produced as a cartoon film by Nederlandfilm in 1943.[9] The film was mostly financed with German money. While lavishly budgeted, it was never presented publicly, possibly because most Dutch Jews had already been transported to the concentration camps and the film came too late to be useful as a propaganda piece, possibly also because the Dutch collaborationist Department of People's Information, Service and Arts objected to the fact that the fox, an animal traditionally seen as "villainous", should be used as a hero.[10] In 1991, parts of the film were found again in the German Bundesarchiv. In 2005, more pieces were found, and the film has been restored. The reconstructed film was shown during the 2006 Holland Animation Film Festival in Utrecht and during the KLIK! Amsterdam Animation Festival in 2008, in the Netherlands.[11]

Other adaptations, versions, and references

In movies and television series

- Ladislas Starevich's 1930 puppet-animated feature film Le Roman de Renard (The Tale of the Fox) featured the Reynard character as the protagonist.

- The documentary film Black Fox (1962) parallels Hitler's rise to power with the Reynard fable.

- Initially, Walt Disney Animation Studios considered a movie about Reynard. However, due to Walt Disney's concern that Reynard was an unsuitable choice for a hero, the studio decided to make Reynard the antagonist of a single narrative feature film named Chanticleer and Reynard (based on Edmond Rostand's Chanticleer) but the production was scrapped in the mid-1960s, in favor of The Sword in the Stone (1963). Ken Anderson used the character designs for Robin Hood (1973) such as the animal counterparts (e.g. Robin Hood like Reynard is a fox while the Sheriff of Nottingham like Isengrim is a wolf).

- In 1985, a French animated series, "Moi Renart" (I Reynard), was created that was loosely based on Reynard's tales. In it, the original animals are anthropomorphic humanoid animals (to the point that, primary, only their heads are that of animals) and the action occurs in modern Paris with other anthropomorphic animals in human roles. Reynard is a young mischievous fox with a little monkey pet called Marmouset (an original creation). He sets off into Paris in order to discover the city, get a job and visit his grumpy and stingy uncle, Isengrim, who is a deluxe car salesman, and his reasonable yet dreamy she-wolf aunt, Hersent. Reynard meets Hermeline, a young and charming motorbike-riding vixen journalist. He immediately falls in love with her and tries to win her heart during several of the episodes. As Reynard establishes himself in Paris, he creates a small company that shares his name which offers to do any job for anyone, from impersonating female maids to opera singers. To help with this, he is a master of disguise and is a bit of a kleptomaniac, which gets him into trouble from police chief Chantecler (a rooster) who often sends cat police inspector Tybalt after him to thwart his plans.

- In 2005, a Luxembourg-based animation studio released an all CGI film titled Le Roman de Renart, based on the same fable.

- In 2016, Syfy's television series, The Magicians, Reynard is summoned accidentally.

In literature

- Tybalt in Shakespeare's Romeo and Juliet is named after the cat in Reynard the Fox (and is called 'Prince of Cats' by Mercutio in reference to this).

- Jonson's play Volpone is heavily indebted to Reynard.[12]

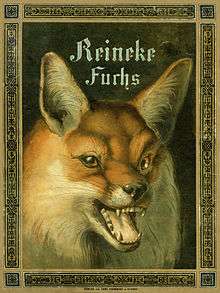

- Goethe dealt with Reynard in his fable Reineke Fuchs.[13]

- Fedor Flinzer illustrated Reineke Fuchs (Reynard the Fox) for children.

- French artist Rémy Lejeune (Ladoré) illustrated Les Aventures de Maître Renart et d'Ysengrin son compère, "Bibliolâtres de France" editions (1960)

- In Friedrich Nietzsche's The Twilight of the Idols, Nietzsche uses Reynard the Fox as an example of a dialectician.[14]

- Louis Paul Boon's novel Wapenbroeders (Brothers in Arms, 1955) is an extensive reworking of the whole tale.

- Reynard the Fox makes a short but significant appearance at the end of The Magician King, when he is accidentally summoned.

- Reynard, a genetically modified part-fox, is a major character in John Crowley's novel Beasts.

- A human version of the character appears in David R. Witanowski's novel Reynard the Fox.[15]

In art

- Dutch modern artist Leonard van Munster made an installation titled "The surrender of Reynard the Fox".

- German artist Johann Heinrich Ramberg made a series of 30 drawings which he also etched and published in 1825.[16]

In music

Reynard the Fox is the name of a number of traditional folk songs (Roud 190, 358 and 1868).

- Renard is a one-act chamber opera-ballet by Igor Stravinsky, written in 1916, with text by the composer based on Russian folk tales from the collection by Alexander Afanasyev.

- Andy Irvine recorded the traditional Irish song "Reynard The Fox" with Sweeney's Men on their 1968 debut album Sweeney's Men.

- Fairport Convention recorded the traditional English song called "Reynard The Fox"(Roud 190) (collected by Ralph Vaughan Williams in Norfolk)[17] on their 1978 album Tipplers Tales.

- Martin Carthy recorded the song "Reynard the Fox"(Roud 1868) on his 1982 album Out of the Cut.

- Julian Cope wrote a song called "Reynard the Fox" which he recorded on his 1984 album Fried.

- Brass Monkey recorded a version of the song collected by Ralph Vaughan Williams as "The Foxhunt"(Roud 190) sung by Martin Carthy on their 1986 album See How It Runs.

- Country Teasers wrote a song called "Reynard the Fox", which appears on the 1999 album Destroy All Human Life.

In advertising

In comics

- Reynard is portrayed as a character in Gunnerkrigg Court as Reynardine, a fox demon who can possess "anything with eyes", including living beings and, in his current form, a plush wolf toy. Gunnerkrigg Court also has Ysengrin, an Ysengrim analog.

- Reynard is portrayed as a character in Fables, as a smart and cunning fox who is loyal to Snow White and Fabletown, despite being one of the Fables segregated to the upstate New York "Farm" due to his non-human appearance. He initially appears as a physically normal fox, anthropomorphized only in his ability to think and speak as humans do; later, he is granted the ability to assume a handsome human appearance.

- The French comic De cape et de crocs takes place in an alternative 17th century where anthropomorphic animals live among humans. One of the two main characters, Armand Raynal de Maupertuis, is a French fox based on Reynard while his companion, Don Lope de Villalobos y Sangrin, is a Spanish wolf based on Isengrim (which is spelled Ysengrin in French).

See also

- Fabliau

- Foxes in culture

- Kitsune

- Króka-Refs saga

- Maleperduis

- Native American coyote mythology

- Trickster

- Ysengrimus

Notes

- ↑ Bianciotto, G. (2005). Introduction. In Le Roman de Renart. Paris: Librairie Générale Française (Livre de poche) ISBN 978-2-253-08698-7

- 1 2 3 Briggs, Asa (ed.) (1989) The Longman Encyclopedia, Longman, ISBN 0-582-91620-8

- ↑ Benton, Janetta Rebold (1 April 1997). Holy Terrors: Gargoyles on Medieval Buildings. Abbeville Press. p. 83. ISBN 978-0-7892-0182-9.

- 1 2 Bouwman, André; Besamusca, Bart (2009). Of Reynaert the Fox: Text and Facing Translation of the Middle Dutch Beast Epic Van Den Vos Reynaerde. Amsterdam: Amsterdam University Press. pp. 42–43. ISBN 908964024X.

- ↑ Lemma = Waal, INL

- 1 2 Renert at the European Literary Characters website. Retrieved on 22 April 2015.

- ↑ Rodange, Michel (2010). "Renert, oder de Fuuss Am Frack an a Mansgresst". Kessinger Publishing. Retrieved on 22 April 2015.

- ↑ Reynard the Fox and the Jew Animal by Egbert Barten and Gerard Groeneveld Archived June 18, 2006, at the Wayback Machine.

- ↑ Animation World Network. "Reynard the Fox and the Jew Animal". Awn.com. Retrieved 2012-02-20.

- ↑ Animation World Network (1996-10-01). "Reynard the Fox and the Jew Animal, page 6". Awn.com. Retrieved 2012-02-20.

- ↑ "Animaties over oorlog op filmfestival" (in Dutch). ANP.

- ↑ Jonson, B. (1999) Brian Parker and David Bevington (eds.), Volpone, Manchester, Manchester University Press pp. 3-6 ISBN 978-0-7190-5182-1

- ↑ Reineke Fuchs (Goethe) in German wikipedia

- ↑ Twilight of the Idols, Nietzsche, p. 13

- ↑ Witanowski, David R. (13 August 2012). "Reynard the Fox". Calliope Press – via Amazon.

- ↑ "Reineke Fuchs. In 30 Blattern gezeichnet und radirt von Johann Heinrich Ramberg." Hannover 1826. New edition with colored prints 2016 ISBN 978-3-89739-854-2

- ↑ "Reynard the Fox" at Mainly Norfolk: English Folk and Other Good Music website. Retrieved on 22 April 2015.

Bibliography

- Bonafin, Massimo, Le malizie della volpe: Parola letteraria e motivi etnici nel Roman de Renart (Rome: Carocci editore, 2006) (Biblioteca Medievale Saggi). cf. here an abstract of this book & cf. here a review of this book unfortunately not yet translated in English.

- Zebracki, Martin, Het grenzeloze land van Reynaerde [The boundless country of [the Fox] Reynaert]. Geografie 20 (2011: 2), pp. 30–33.

- Johann Heinrich Ramberg (artist), Dietrich Wilhelm Soltau (author), Waltraud Maierhofer (editor): "Reineke Fuchs – Reynard the Fox. 31 Originalzeichnungen u. neu kolorierte Radierungen m. Auszügen aus d. deutschen Übersetzung des Epos im populären Stil v. Soltau | 31 original drawings and newly colored etchings with excerpts from the English translation of the burlesque poem by Soltau." VDG Weimar, Weimar 2016. ISBN 978-3-89739-854-2.

External links

| Look up renard in Wiktionary, the free dictionary. |

| Wikisource has original works on the topic: Reynard |

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Reynard. |

- Le roman de Renart In French.

- The History of Reynard The Fox by Henry Morley, 1889.

- Reynard The Fox, article from the 1911 edition of Encyclopædia Britannica

- Full text of the Middle Dutch poem

- Full text of the Middle Dutch poem with notes

- Reinardus, the journal for the International Reynard Society.

- Anne Lair, "The History of Reynard the Fox: How Medieval Literature Reflects Culture," in: Falling into Medievalism, ed. Anne Lair and Richard Utz. Special Issue of UNIversitas: The University of Northern Iowa Journal of Research, Scholarship, and Creative Activity, 2.1 (2006).

- Complete Bibliography on Reynard from the Archives de littérature du Moyen Age

- Reynard The Fox in the Vondelpark 03 03 2010