River Tame, Greater Manchester

| River Tame | |

|---|---|

|

River Tame, seen here near Reddish Vale. | |

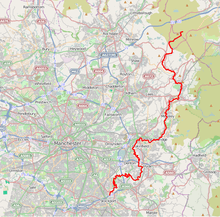

The River Tame is highlighted in red Coordinates: 53°24′51″N 2°09′25″W / 53.4142°N 2.15689°W | |

| Country | England |

| Basin | |

| Main source | Denshaw, Greater Manchester |

| River mouth |

River Mersey 40 m (130 ft)[1] |

| Basin size | 146 km2 (56 sq mi)[2] |

| Physical characteristics | |

| Length | 47.7 km (29.6 mi) |

The River Tame flows through Greater Manchester, England.

Sources

The Tame rises on Denshaw Moor in Greater Manchester, close to the border with West Yorkshire but within the historic West Riding of Yorkshire.

Course

Most of the river's catchment lies on the western flank of the Pennines. The named river starts as compensation flow (that is, a guaranteed minimum discharge[3]) from Readycon Dean Reservoir in the moors above Denshaw. The source is a little further north, just over the county border in West Yorkshire, close to the Pennine Way. The highest point of the catchment is Greater Manchester's highest point at Black Chew Head.

The river flows generally south through Delph, Uppermill, Mossley, Stalybridge, Ashton-under-Lyne, Dukinfield, Haughton Green, Denton and Hyde. The Division Bridge (which spans the river at Mossley), marks the meeting point of the traditional boundaries of Lancashire, Yorkshire and Cheshire. The section through Stalybridge was once mooted as a diversion route for the restoration of the Huddersfield Narrow Canal. For all its remaining course after the Division Bridge, the river marks much of the historical boundary dividing Cheshire and Lancashire, before confluence with the River Goyt to form the River Mersey at Stockport. The 19th century industrial concentrations in the above-named urban areas resulted in the Tame being a much polluted waterway. As well as industrial pollution from the dyes and bleaches used in textile mills, effluent from specialised paper-making [cigarette papers], engineering effluents, including base metal washings from battery manufacture, phenols from the huge coal-gas plant in Denton, rain-wash from roads and abandoned coal spoil heaps there was also the sewage effluent from the surrounding population. Up to two-thirds of the river's flow at its confluence with the Goyt had passed through a sewage works. The anti-pollution efforts of the last thirty years of the 20th century have resulted in the positive fauna distributions listed below.

The Centre for Ecology and Hydrology measures the flow at two points for the National River Flow Archive, at Portwood weir (Stockport) and at Broomstairs weir (Denton). Portwood weir is 1¼ miles above the confluence with the Mersey and contains the great majority of the final flow (with the exception of waste water from a concrete facility).[4]

Mouth

The Tame joins the River Goyt at Stockport, forming the River Mersey which eventually flows into the Irish Sea just past Liverpool.

Toponomy

The name Tame is attached to rivers across the UK in several forms, including Thames, Thame, Taff, and Tamar, alongside two other instances of Tame.[5][6] The name is Celtic in origin, but the meaning is uncertain.[7][8] Dark river or dark one has been suggested,[9][10] but Ekwall[7] finds it unlikely; Mills suggests it may simply mean river (c.f. Avon, Humber, Tyne).[6] The names of the Mersey's co-tributaries Etherow and Goyt are equally ancient and mysterious.[7] Mersey is an Old English name (i.e. more recent) derived from "river at the boundary". The earlier name is lost: Dodgson suggests that Tame may have been the name for the whole of the Mersey.[8]

The Metropolitan Borough of Tameside is named after the river. While it flows through the borough, the river neither rises nor finishes inside its boundaries; however, most of the built-up area alongside the river is in Tameside.

Fauna

The fish species present vary along the river's length. The lower reaches (near Reddish Vale Country Park) are home to coarse fish such as gudgeon (Gobio gobio), chub (Leuciscus cephalus), and roach (Rutilus rutilus); pike (Esox lucius) and perch (Perca fluviatilis) are also present. The upper reaches (above Ashton) support brown trout (Salmo trutta) and smaller numbers of some coarse fish. The populations are self-sustaining.[11] Furthermore,

- Carr Brook (from its source to the Tame)

- Diggle Brook (from Diggle Reservoir to the Tame)

- Hull Brook (Head of Lower Castleshaw Reservoir to the Tame)

- Swineshaw Brook (from the Head of Swineshaw Reservoir to the Tame)

- and the Tame (from the Head of Readycon Dean Reservoir to foot of New Years Bridge Reservoir)

are all declared as salmonid waters by statute, and as such have set physical and chemical water quality objectives.[12][13]

Hull Brook is a Site of Biological Importance (SBI). Hull Brook and Castleshaw Reservoir have populations of white-clawed crayfish.[14] The river is now clean enough in principle to support otters, but none were found in a survey in 2000–2002.[15]

Tributaries

- Swineshaw Brook

- Carr Brook

- Chew Brook

- Greenfield Brook

- Diggle Brook

- Hull Brook

- Rams Brook

- Summer Hill Brook

- Lumb Hole Brook

- Cherry Brook

- Brimmy Brook

- Readycon Dean Brook

- Dowry Water

See also

References

Notes

- ↑ Boyce, D (August 2005). "Mersey and Bollin Catchment abstraction management strategy" (pdf). Environment Agency North West, Warrington. p. 5. Retrieved 2007-03-13.

- ↑ Boyce, D (March 2004). "The Tame, Goyt and Etherow catchement abstraction management strategy" (pdf). Environment Agency, Warrington. p. 6. Retrieved 2007-03-13.

- ↑ "Glossary". Centre for Ecology and Hydrology. Retrieved 2008-01-08.

- ↑ "69027 - Tame at Portwood". The National River Flow Archive. Centre for Ecology and Hydrology. Retrieved 2008-01-08.

- ↑ Ekwall, Bror Oscar Eilert (1922). The Place-Names of Lancashire. Publications of the University of Manchester, English series, number 11. Manchester.

- 1 2 Mills, A D (1998). A dictionary of English place-names. Oxford: Oxford University Press. ISBN 0-19-280074-4.

- 1 2 3 Ekwall, Eilert (1928). English river names. Oxford: Clarendon Press.

- 1 2 Dodgson, J McN (1966). The place-names of Cheshire, part 1. Cambridge University Press.

- ↑ Ekwall, Bror Oscar Eilert (1947). The Concise Oxford Dictionary of English Place Names. Oxford: Clarendon Press.

- ↑ Potter, Simeon M A (1955). Cheshire Place-Names (Reprinted from the Transactions of the Historic Society of Lancashire and Cheshire). London: International University Booksellers.

- ↑ "River Tame fish survey". Environment Agency. 8 December 2004. Archived from the original on February 25, 2006. Retrieved 2008-01-07.

- ↑ "Freshwater Fish Directive". DEFRA. 13 January 2004. Retrieved 2008-01-08.

- ↑ "Schedule 2 Freshwaters in England and Wales to which Classification SW applies" (PDF). DEFRA. July 1998. Retrieved 2008-01-08.

- ↑ "Report on update of sites of biological importance" (Word document). Oldham MBC. 15 October 2007. Retrieved 2008-01-20.

- ↑ "Fourth Otter Survey of England 2000–2002" (PDF). Environment Agency. 2002. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2007-12-21. Retrieved 2008-02-04.

Bibliography

- Carter, Charles Frederick, ed. (1962). Manchester and its region : a survey prepared for the meeting of the British Association for the Advancement of Science held in Manchester August 29 to September 5, 1962. Manchester: Manchester University Press.

- Arrowsmith, Peter (1997). Stockport : a history. Stockport: Stockport Metropolitan Borough Council. ISBN 0-905164-99-7.

- Holden, Roger N. (1998). Stott & Sons : architects of the Lancashire cotton mill. Lancaster: Carnegie. ISBN 1-85936-047-5.

- Williams, Mike; D A Farnie (1992). Cotton mills in Greater Manchester. Preston: Carnegie. ISBN 0-948789-69-7.

- Greater Manchester Council (1981). Tame Valley : report of survey and issues. Greater Manchester Council.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to River Tame, Greater Manchester. |