Robert Bell (Speaker)

| Robert Bell | |

|---|---|

| Speaker of the British House of Commons | |

|

In office 1572–1576 | |

| Preceded by | Sir Christopher Wray |

| Succeeded by | Sir John Popham |

| Serjeant-at-Law | |

|

In office 22 January 1577 – 25 July 1577 | |

| Preceded by | Sir Edward Saunders |

| Succeeded by | Sir John Jeffery |

| Lord Chief Baron of the Exchequer | |

|

In office 24 January 1577 – 27 July 1577 | |

Sir Robert Bell SL (died 1577) of Beaupre Hall, Norfolk, was a Speaker of the House of Commons (1572–1576), who served during the reign of Queen Elizabeth I.

He was legal counsel (1560) and recorder (1561) for King's Lynn, legal counsel for Great Yarmouth (1562-1563),[1] and justice of the peace of the quorum for Norfolk (1564). He became a bencher in the Middle Temple in 1565 and was elected Autumn Reader that same year and Lent Reader in 1571.[2] In 1576 he was appointed Commissioner of Grain, Musters by 1576 and in 1577 he was knighted and appointed Serjeant-at-Law and Chief Baron of the Exchequer.[2]

Marriages

Robert Bell is reported to have married:

1. Mary Chester, daughter of Anthony Chester.[1][3]

2. Elizabeth Anderson (d.1556-58?), widowed daughter in law of Edmund Anderson, Chief Justice of the Common Pleas.[3]

3. Dorothie, daughter and co-heiress of Edmonde Beaupre', Esq., d. 1567, and Katherine Wynter, widow of John Wynter (Captain of the Castle of Mayett, France), daughter of Phillip Bedingfeld of Ditchingham, Norfolk.[1][4][5]

Education and religion

Bell may have been privately tutored or mentored by John Cheke,[3] a close friend and kinsman of William Cecil, (Lord Burghley). Cecil (Lord Burghley), was Queen Elizabeth's 'chief advisor', who has been 'appraised as' "the probable behind the scenes architect of the '1566 succession question."[4] Cecil is credited with nominating Bell to the succession committee to represent the House of Commons and also with recommending Bell for Speaker in 1572.[4] John Cheke was also a relative and close friend of Peter Osbourne, a fellow Exchequer colleague of Bell's, whose daughter Anne, married Bell's first son and heir Edmond.

In 1566, Robert Bell was lampooned by Thomas Norton as "Bell the Orator" together with others who served on the succession committee. Most of the individuals featured in this publication were Puritans, for example, Christopher Yelverton who is styled "Yelverton the Poet."[2] HoP [3]

Scholars have suggested that Robert Bell may have attended Cambridge (which had Protestant leanings 16th century),[2][5][6] which can be supported by his political alignments during the 1566, parliamentary session, in particular, "Mr. Bell's complices"... (Richard Kingsmill and Robert Monson)[2] HoP with whom the Queen referred, during the debate that touched the issues of the succession question.

He gained admittance to the Middle Temple where he excelled, first elected to sit as a bencher and subsequently elected Lent and Autumn Reader.

During the period that he attended the Middle Temple, the religious denomination of the pupils and Masters of the bench was primarily Catholic, with emerging factions of Protestants, balancing the Elizabethan membership. The register that would have recorded where he had been formerly educated, or where he attended church has long been lost.[3][7]

Career

Bell, achieved notable success at the beginning of his career, specifically (6 March 1559), upon accomplishing favorable results for the patentees of the lands of John White, bishop of Winchester, involving a suit that protected their interest; of which he was of counsel together with Alexander Nowell.[8]

His career was further secured and launched with his fortunate marriage (15 October 1559), to the baroness Dorothie Beaupre. This afforded him not only a family, but a large estate in Outwell, along with the local offices and status that came with it; including the office of MP, for King's Lynn. During the 1563, 1566, and 1571 parliaments, Bell made a 'thorough' nuisance of himself to the government, and was considered a radical; noted by William Cecil as one of the two leading trouble makers during the 1566, session.[2][5]

Additionally, it would appear that, Elizabeth I, witnessed this 'maverick' style of behavior, as 'on 19 October 1566, '[Bell] did argue very boldly' to pursue the succession question; "in the face of the Queen's command to leave it alone". "In her own words 'Mr Bell with his complices... must needs prefer their speeches to the upper house to have you, my lords, consent with them, whereby you were seduced, and of simplicity did assent unto it'.[2]

Of course, it should be clarified that he was merely conveying the concern of the House, following Elizabeth's near death illness, and for the realm, which may have collapsed into civil war upon her death.

Five years later during the next parliament (5 April 1571) he re focused his attention, and [boldly'] launched an attack on the Queen's purveyors, who took 'under pretence of her Majesty's service what they would at what price they themselves liked...' 'Later in 1576, this speech was recalled by Peter Wentworth during his motion for liberty of speech: 'The last Parliament he that is now Speaker uttered a very good speech for the calling in of certain licenses granted to four courtiers to the utter undoing of 6,000 or 8,000 of the Queen Majesty's subjects. This speech was so disliked by some of the [Privy] council, that he was sent for and so hardly dealt [Warned] with that he came into the House with such an amazed countenance that it daunted all the House,...' to the extent that for several day's no matter of great importance was raised or considered.[2] DNB

Nevertheless, on 19 April 1571, he was an advocate for the residents of less fortunate boroughs, " 'and in a loving discourse showed that it was necessary that all places should be provided for equally'." "but because some boroughs had not 'wealth to provide fit men' outsiders could sometimes be returned and no harm done". He further, proposed that all boroughs who sought to nominate a nobleman, should suffer a substantial financial penalty [£40], "mindful, no doubt of the power of the Duke of Norfolk in his county."[2]

From 1570–72, he served as crown counsel,[5] and, perhaps, it was Bell's outspokenness, hitherto, that revealed his niche, as shortly following these events, he was recommended by William Cecil for Speaker (Prolocutor),[4] elected by the House, and approved by Elizabeth I, 8 May 1572.[9] 'The Queen on her part', he was told, had 'sufficiently heard of your truth and fidelity towards her and... understandith your ability to accomplish the same.'[2]

Bell's second disabling speech of that day was full of luminous detail and "was a model of circumspection:, a lawyer's piece larded with legal precedent; in his careful transmission of royal messages and his preference that attempts to persuade a reluctant queen should be by written arguments rather than by his spoken word;"[5] 'some of it is worth quoting'... 'as an early example of the taste for precedents that became common place in the history of the House during the seventeenth century.'

- ..The transcription of Mr. Bell's second Oration.

Your highness’ noble progenitors kings of this realm not many years after the conquest did publish and set forth divers ordinances and constitutions. But the same was not confirmed by parliament, and therefore proved perilous as well in not sufficiently providing for those which deserved well nor sufficient authority for punishment of them which deserved contrary. Whereupon King Henry III finding no such perfection therein as he did desire, by the mature deliberation and grave advice of his lords and council did condescend to walk in a new course of government, in which he determined that all things should be provided for by authority of parliament; and shortly after called two of the same, the first at Merton, a the second at Marlborough, b in which divers things before set forth but by charter were then confirmed and ratified by parliament, which have since been received and obeyed; who after that experience had taught him the benefit thereof did prosecute the same all the time of the rest of his reign. And King Edward I did the like, who called a parliament for one only cause, which was for that temporal possessions were gathered together by abbots and other spiritual persons and corporations, to restrain the same from that time forwards and to provide that they should live only of their spiritual promotions. c I mean to note principally but two or three statutes for my purpose. In the xiii th year of his reign he called another parliament for the punishment of felonies and robberies done by vagabonds. d In the xiiii th [recte 13 Ed. I] year of his reign he called another parliament for the only cause of the relief of his merchants, called statutum de mercatoribus. e And after him his son King Edward II in the ixth year of his reign called a parliament for the ending of a controversy between the spirituality and laity concerning discipline. f These few statutes I thought good to recite, whereby it may well appear what diligent care your Majesty’s progenitors had for reformation of every small cause, and what obedience was in the subjects. Every parliament a cause by itself, and the success thereof had good allowance in the time of King Edward III, for he finding by experience the benefit thereof, in the fourth year of his reign procured it to be enacted that there should every year once at the least a parliament be kept, and oftener if need were. g I move this the rather because I think many marvel of the sudden calling of this parliament this time of the year so shortly after the end of the last. These few examples may answer such objections and satisfy every man that it is their duties to attend. If the causes before remembered were allowed sufficient causes [to] call parliaments, then let us weigh them in balances with the weight of those causes for which this parliament is called; and if for punishment of vagabonds were a sufficient cause to call a parliament, as it was indeed then great and now not small; if the relief of merchants were a sufficient cause to call a parliament, if the determination of a controversy between the clergy and laity were a sufficient cause, let us indifferently consider whether now far greater be offered unto us, I mean the preservation of the prince upon which one only cause, who seeth not that all these causes and all other causes which may concern this state doth depend. The want of good provision in one parliament may be an overthrow to the good meaning of all the rest ... [2]

While Speaker, he presided over some of the more dynamic issues of the Elizabethan Parliaments, notably, the security of the realm, and a session concerning the question of Mary, Queen of Scots; where he was advised to shorten the discussion upon receiving a royal message that was whispered in his ear by Christopher Hatton.[10]

In 1575, he revisited the succession question, and on this occasion respectfully, petitioned Elizabeth "to make the kingdom further happy in her marriage, so that her people might hope for a continual succession of benefits in her posterity." Although he exhibited great courtesy during the course of his plea, Elizabeth still refused.[9]

Bell helped forge the realm under Elizabeth's rule, and following the 1576 session he was honorably rewarded and nominated for membership of a high powered committee for a special visitation of Oxford, that included Christopher Wray, Edwin Sandys then bishop of London and John Piers then bishop of Rochester and four others. (State Papers, Domestic, Elizabeth, p. 543)

Honors

In 1577, during the New Year's promotions, Elizabeth I, conferred a knighthood to him, made him her Serjeant-at-Law, and appointed him Chief Baron of the Exchequer; a post that he retained during the period that Francis Drake wrote the government, claiming his bounty to build his three ships in Aldeburgh,* together with the arrangements he secured from his investors, for his 1577, voyage to circumnavigate the globe.[3][11]

Bells' contemporaries respected his contributions to society; notably, James Dyer, Edmund Plowden and the historian, William Camden who considered him a 'lawyer of great renowne,' a "Sage and grave man, famous for his knowledge in the law, and deserving the character of an upright judge." [12][1][5]

Death and commemoration

While presiding as judge, at the Oxford assizes, (afterward deemed the Black Assizes), he became exposed to prisoners of foul condition during the trial of a book seller who had slandered the Queen. This stench is thought to have caused a pestilent vapour and Bell (along with an estimated 300 others) caught gaol fever.[5], (Camden, Annals, bk. 2.376)

He then moved on to Leominster, and after presiding over the assize in that district, fell ill. On 25 July, he drafted a codicil to his will, where he made his 'Loving wife Dorothie sole executor' and directed the selling of certain property for payment of debts, and future provisions for his family:

- "This Codicell and Addicon, made by me Sr Robert Bell knight Cheiff Barron of her maties Exchequer the xxvijth Daye of Julye in the yeare of oure Lorde God one Thowsande fyve hundred Seaventie Seaven, wch I will and my trewe meaninge is that it shalbe annexed and added unto my last will and Testament remayninge at my howse at Bewprehall in Norff ffirst I will my Bodye shalbe buryed in the same Towne where yt shall please God to call me at the discreation of my cheff Sr’nnts that shalbe aboute me at the Daye of my death...."

- ..."and the money thereof cominge to be ymployed towardes the payment of my Debtes and bringinge upp of my children at the order and discreation of my saide Executrix "[13]

Prior to his illness, he had devoted his time and attention to the expansion of his family home, and had commissioned The Guild of Glaziers? with the production of heraldic stained glass panels, representing the various marital alliances that were shared by the Beaupre's and the Bell's.

The panels were originally bourne and incorporated around the entry way of Beaupre Hall, Norfolk, and were later cut down and relocated to windows in the rear of the Hall; perhaps after 1730 when the antiquary, Beaupre Bell, succeeded to the property.[3][9]

After his death in 1741, Mr. Greaves succeeded, who had married Beaupre Bell's sister (of whom we owe for saving the glass relics). Their daughter Jane brought it by marriage to the Townley family, who held Beaupre Hall until it passed into the hands of Mr. Edward Fordham Newling, and his brother,[14] who anticipated the Hall's ruin, and wished that the stained glass panels would be placed in the care and possession of the Victoria & Albert Museum, London, where they are currently on display.

Two panels of similar design had been commissioned in 1577:

- The Arms of Sir Robert Bell.

- The Arms of Sir Robert Bell impaling Harington (the Harington Arms are depicted with the cadency mark 'a label')---John Harington, first Baron Harington of Exton (1539/40–1613) who married Anne (c.1554–1620), the daughter and heir of Robert Keilwey, Lent Reader, Treasurer and member of the Inner Temple.[3]

Sir John's father, Sir James Harington of Exton Hall, Rutland, married Lucy, daughter of William Sidney of Penshurst, Kent.

Sir William Sidney's son, Henry Sidney lord deputy of Ireland, was a neighbour of John Peyton and Dorothy daughter of Sir John Tyndale. The Peytons' second son, John Peyton "served in Ireland under their friend and neighbour Sir Henry Sidney of Penshurst, and in 1568, he was again in Ireland with Sidney, then lord deputy and had become a member of Sidney's household."[15]

After Bell's untimely death in 1577, John Peyton married Bell's widow Dorothy, where from her estate, Peyton gained position and status in the county of Norfolk, and later became lieutenant of the Tower of London.

Descendants

"Amongst the many great families with whom the Bells were connected by their various marriages, we may mention.... Beaupre, [Montfort] , De Vere, Bedingfeld, Knyvett,Osbourne, Wiseman, Deering, Chester, Oxburgh, Le Strange, Dorewood, Oldfield, Peyton, and Hobart, all persons of great eminence and distinction."[9][16]

1. His first son, Sir Edmond Bell (de Beaupre)[17] bap. 7 April 1562, bur. 22 Dec 1607, MP for King's Lynn, & Aldeburgh 'invested heavily in privateering,'[18][19] married 1., Anne the daughter of Peter Osbourne and Anne Hays 2. Muriell Knyvet the daughter of Thomas Knyvet, 1st Baron Knyvet High Sheriff of Norfolk (c. 1539–1618) and Merriell Parry, the daughter of Thomas Parry (Comptroller of the Household) and Anne Reade.

2. His second son Sir Robert Bell (de Beaupre)[17] b. (c. 1563, d. 1639), was a 'Captain of a company in the low countries' MP, built gun ships for the navy, (c. 1600) married Elizabeth Inkpen.

3. His third son, Sinolphus Bell, Esq., b. March 1564, d. 1628, of Thorpe Manor, issue 8 sons, 3 dau., of Norfolk, married Jane (Anne) daughter of Christopher Calthrop and Jane Rookwood (daughter of Roger Rookwood) is listed among the knights of a committee to drain the fens.

4. His fourth son, Beaupre Bell b. c. 1570, d. 1638, literary scholar of Cambridge, admitted to Lincolns Inn, 1594, was made Governor of the Tower of London in 1599.[20]

5. His fifth son, Phillip Bell b. 14 June 1574, d. after 1630, Fellow of Queens College, Cambridge (1593–7)

6. His daughter, Margaret Bell b. before 1561, d. 14 September 1591, married Sir Nicholas Le Strange of Norfolk; the son of Sir Hamon Le Strange (c.1534–1580) and Elizabeth Hastings; daughter of Sir Hugh Hastings of Elsing, 14th Lord Hastings (d. c.1540) and Catherine Le Strange (d. 2 February 1558).

7. His daughter, Dorothy b. 19 October 1572, d. 30 April 1640, married Henry Hobart,[21] Chief Justice of the Common Pleas; who laboured together with Francis Bacon, to draft and procure the charters for the London and Plymouth Company.[22]

8. His daughter, Frances b. (posthumous) 2 December 1577, d. 9 November 1657, married Sir Anthony Dering of Kent (1558–1636), JP, of Surrenden Dering in Pluckley, Kent; the parents of Sir Edward Dering, 1st baronet (1598–1644), who married Elizabeth (1602–1622), daughter of Sir Nicholas Tufton, 1st earl of Thanet.[23]

Following the Elizabethan era, Sir Robert Bell's descendants set sail for America, and arrived in Jamestown, Virginia, before and after the Mayflower landed on Plymouth Rock.[3]

Heraldry

The Arms of Sir Robert Bell: Sable a Fess Ermine between three Church Bells Argent The Crest is upon a Helm on a Mount Vert a Phoenix Rising wings elevated and inverted Or armed Sable

Sources

- 1 2 Foss, E., Lives of the Judges, Vol. V, London 1857, p. 458-61

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 Hasler, P. W., HoP: House of Commons 1558–1603, HMSO 1981, p. 421-4

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 Bell, R.R.L., Tudor Bell's Sound Out, pb, 7 September 2006

- 1 2 3 MacCaffrey, W. T., 'Cecil William, first Baron Burghley (1520/21–1598),’ODNB, OUP, 2004 accessed 15 April 2005

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 Graves, M. A.R., ‘Bell, Sir Robert (d. 1577)',ODNB, OUP, 2004 accessed 13 Feb 2005

- ↑ "Bell, Robert (BL565R)". A Cambridge Alumni Database. University of Cambridge.

- ↑ Williamson, J. B., The History of the Temple of London, London, pb. John Murray (2nd ed. 1925)

- ↑ House of Commons, Journal Volume 1, 6 March 1559, pb. 1802, Sponsor BHOL: History of Parliament Trust

- 1 2 3 4 Manning, J. A., Speakers, pb. Myers and Company, London p. 242, 245

- ↑ MacCaffrey, W. T., ‘Hatton, Sir Christopher (c.1540–1591)’, ODNB, OUP, 2004 accessed 7 May 2005

- ↑ Bawlf, S., The Secret Voyage of Sir Francis Drake 1577–1580, pb. Walker Publishing Co. 2003, p. 67

- ↑ Hasler, P. W., HoP: House of Commons 1558–1603, HMSO 1981, p. 421-4 [Bells second oration.] – Trinity Dublin, Thomas Cromwell's jnl. citing the following: a: The provisions of Merton (1236) the comprehensive statute setting out the law on land tenure, baronial rights etc. b: The statute of Marlborough (1267) of similar content. c: The statute of Mortmain (1279) which restricted grants to religious foundations. d: The statute of Winchester, crucial in the history of criminal law. e: The statute of Merchants (1285), which clarified the statute of Acton Burnell (1283) devised to meet the grievances of merchants who found it difficult to collect their debts. f: The Articles of the Clergy (1315) . g: A reference to clause 14 of 4 Ed. III (1330) to this effect. The statute fell into desuetude after the 1340s.

- ↑ O'Donoghue, M.P.D., Transcription Report, The National Archives, UK, Catalog Reference Prob. 11/59, Image Reference 364 (C)

- ↑ Hussey, C., Beaupre Hall Wisbech, Coventry Homes and Gardens Old & New, pb. Country Life, 1923

- ↑ Evans, H. M. E., ‘Peyton, Sir John (1544–1630)’, ODNB, OUP, 2004 accessed 7 May 2005

- ↑ Coll Arm Ms, The Visitations of Norfolk, 1563, William Hervey 1589, Robert Cooke and 1613, John Raven, p. 33–34 Bell. Beaupre., Ed. Walter Rye, London 1891

- 1 2 O'Donoghue, M.P.D., Transcription Report, The National Archives, UK, Catalog Reference Prob. 11/51, Image Reference 18, (C)Crown Copyright

- ↑ Hasler, P. W., HoP: House of Commons 1558–1603, HMSO 1981, p. 421-4 [Bells second oration.] – Trinity Dublin, Thomas Cromwell's jnl. citing the following: a: The provisions of Merton (1236) the comprehensive statute setting out the law on land tenure, baronial rights etc. b: The statute of Marlborough (1267) of similar content. c: The statute of Mortmain (1279) which restricted grants to religious foundations. d: The statute of Winchester, crucial in the history of criminal law. e: The statute of Merchants (1285), which clarified the statute of Acton Burnell (1283) devisied to meet the grievances of merchants who found it difficult to collect their debts. f: The Articles of the Clergy (1315) . g: A reference to clause 14 of 4 Ed. III (1330) to this effect. The statute fell into desuetude after the 1340s. [Reproduced with the permission of the Controller of HMSO-2004]

- ↑ The National Archives, UK, Catalog Reference Prob. 11/111, Image Reference 565 (C)

- ↑ Kupperman, K., Puritan Colonization from Providence Island through the Western Design, The William and Mary

- ↑ Woodcock, T., and, Robinson, J. M.,Heraldry in Historic Houses of Great Britain, The National Trust, pb. 2000

- ↑ MacDonald, W., Documentary source book of American History, 1606–1913,1910-20-21

- ↑ Salt, S. P., ‘Dering, Sir Edward, first baronet (1598–1644)’, ODNB, OUP, 2004 accessed 23 May 2005

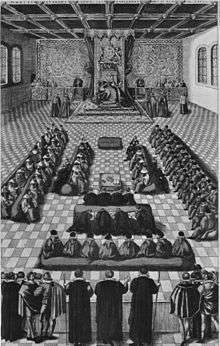

Likeness

NPG, London. (1) Robert Bell, Esq., Speaker 1572, possibly by the artist T. Athlow, (2) Sir Robert Bell, Chief Baron of the Exchequer 1577, by William Camden Edwards, after unknown artist, and the British Museum

| Legal offices | ||

|---|---|---|

| Preceded by Sir Edward Saunders |

Chief Baron of the Exchequer 1577 |

Succeeded by John Jefferay |

.svg.png)