Henry Addington, 1st Viscount Sidmouth

| The Right Honourable The Viscount Sidmouth PC | |

|---|---|

|

Portrait by Sir William Beechey | |

| Prime Minister of the United Kingdom | |

|

In office 14 March 1801 – 10 May 1804 | |

| Monarch | George III |

| Preceded by | William Pitt the Younger |

| Succeeded by | William Pitt the Younger |

| Chancellor of the Exchequer | |

|

In office 17 March 1801 – 10 May 1804 | |

| Monarch | George III |

| Preceded by | William Pitt the Younger |

| Succeeded by | William Pitt the Younger |

| Lord President of the Council | |

|

In office 14 January – 10 July 1805 | |

| Monarch | George III |

| Prime Minister | William Pitt the Younger |

| Preceded by | The Duke of Portland |

| Succeeded by | The Earl Camden |

|

In office 8 October 1806 – 26 March 1807 | |

| Monarch | George III |

| Prime Minister | Spencer Perceval |

| Preceded by | The Earl Fitzwilliam |

| Succeeded by | The Earl Camden |

|

In office 8 April – 11 June 1812 | |

| Preceded by | The Earl Camden |

| Succeeded by | The Earl of Harrowby |

| Home Secretary | |

|

In office 08 June 1812 – 17 January 1822 | |

| Preceded by | Richard Ryder |

| Succeeded by | Robert Peel |

| Personal details | |

| Born |

30 May 1757 Bedford Row, Holborn, Middlesex, England |

| Died |

15 February 1844 (aged 86) White Lodge, Richmond, Surrey, England |

| Political party | Tory |

| Spouse(s) | Ursula Hammond (m. 1781; d. 1811) |

| Alma mater | Brasenose College, Oxford |

| Religion | Church of England |

| Signature |

|

Henry Addington, 1st Viscount Sidmouth, PC (30 May 1757 – 15 February 1844) was a British statesman who served as Prime Minister from 1801 to 1804. He is best known for obtaining the Treaty of Amiens in 1802, an unfavourable peace with Napoleonic France which marked the end of the Second Coalition during the French Revolutionary Wars. When that treaty broke down he resumed the war but he was without allies and conducted a relatively weak defensive war, ahead of what would become the War of the Third Coalition. He was forced from office in favour of William Pitt the Younger, who had preceded Addington as Prime Minister. Addington is also known for his ruthless and efficient crackdown on dissent during a ten-year spell as Home Secretary from 1812 to 1822. He is the longest continuously serving holder of that office since it was created in 1782.

Family

Henry Addington was the son of Anthony Addington, Pitt's physician, and Mary Addington, the daughter of the Rev. Haviland John Hiley, headmaster of Reading School. As a consequence of his father's position, Addington was a childhood friend of William Pitt the Younger. Addington studied at Reading School, Winchester and Brasenose College, Oxford, and then studied law at Lincoln's Inn.

Political career

He was elected to the House of Commons in 1784 as Member of Parliament (MP) for Devizes, and became Speaker of the House of Commons in 1789. In March 1801, William Pitt the Younger resigned from office, ostensibly over the refusal of King George III to remove some of the existing political restrictions on Roman Catholics in Ireland (Catholic Emancipation), but poor health, failure in war, economic collapse, alarming levels of social unrest due to famine, and irreconcilable divisions within the Cabinet also played a role. Both Pitt and the King insisted that Addington take over as Prime Minister, despite his own objections, and his failed attempts to reconcile the King and Pitt.

Prime minister

Foreign policy was the centerpiece of his term in office. Some historians have been highly critical saying it was ignorant and indifferent to Britain's greatest needs. However Thomas Goldsmith argues that Addington and Hawkesbury conducted a logical, consistent, and Euro-centric balance-of-power policy, and one rooted in rules and assumptions governing their conduct, rather than a chaotic free-for-all approach.[1]

Addington's domestic reforms doubled the efficiency of the Income tax. In foreign affairs he secured the Treaty of Amiens, in 1802. While the terms of the Treaty were the bare minimum that the British government could accept, Napoleon Bonaparte would not have agreed to any terms more favourable to the British, and the British government had reached a state of financial collapse, owing to war expenditure, the loss of Continental markets for British goods, and two successive failed harvests that had led to widespread famine and social unrest, rendering peace a necessity. By early 1803 Britain's financial and diplomatic positions had recovered sufficiently to allow Addington to declare war on France, when it became clear that the French would not allow a settlement for the defences of Malta that would have been secure enough to fend off a French invasion that appeared imminent.

At the time and ever since Addington has been criticized for his lackluster conduct of the war and his defensive posture. However without allies, Britain's options were limited to defence. He did increase the forces, provide a tax base that could finance an enlarged war, and seize several French possessions. To gain allies, Addington cultivated better relations with Russia, Austria, and Prussia, that later culminated in the Third Coalition shortly after he left office. Addington also strengthened British defences against a French invasion through the building of Martello towers on the south coast and the raising of more than 600,000 men at arms.[2]

Loss of office

Although the king stood by him it was not enough because Addington did not have a strong enough hold on the two houses of Parliament. By May 1804 partisan criticism of Addington's reasonable and sensible war policies provided the pretext for a parliamentary putsch by the three major factions - Grenvillites, Foxites, and Pittites - who had decided that they should replace Addington's ministry. Addington's greatest failing was his inability to manage a parliamentary majority, by cultivating the loyal support of MPs beyond his own circle and the friends of the King. This combined with his mediocre speaking ability, left him vulnerable to Pitt's mastery of parliamentary management and his unparalleled oratory skills. Pitt's parliamentary assault against Addington in March 1804 led to the slimming of his parliamentary majority to the point where defeat in the House of Commons was imminent.[3]

Lord President and Lord Privy Seal

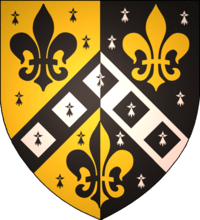

Addington remained an important political figure, however, and the next year he was created Viscount Sidmouth. He served in Pitt's final Cabinet as Lord President of the Council to 1806, and in the Ministry of All the Talents as Lord Privy Seal and again Lord President to 1807.

Home Secretary

He returned to government again as Lord President in March 1812, and, in June of the same year, became Home Secretary. As Home Secretary, Sidmouth countered revolutionary opposition, being responsible for the temporary suspension of habeas corpus in 1817 and the passage of the Six Acts in 1819. His tenure also saw the Peterloo Massacre of 1819. Sidmouth left office in 1822, succeeded as Home Secretary by Sir Robert Peel, but remained in the Cabinet as Minister without Portfolio for the next two years, fruitlessly opposing British recognition of the South American republics. He remained active in the House of Lords for the next few years, making his final speech in opposition to Catholic Emancipation in 1829 and casting his final vote against the Reform Act 1832.

Foundling Hospital

As Prime Minister, in 1802, Addington accepted an honorary position as vice-president for life on the Court of Governors of London's Foundling Hospital for abandoned babies.

Residences and land

Addington maintained homes at Up Ottery, Devon and Bulmershe Court, in what is now the Reading suburb of Woodley, but moved to the White Lodge in Richmond Park when he became Prime Minister. However he maintained links with Woodley and the Reading area, as commander of the Woodley Yeomanry Cavalry and High Steward of Reading. He also donated to the town of Reading the four acres of land that is today the Royal Berkshire Hospital, and his name is commemorated in the town's Sidmouth Street and Addington Road as well as in Sidmouth street in Devizes.

Death

Henry Addington died in London on 15 February 1844 at the age of 86, and was buried in the churchyard at St Mary the Virgin Mortlake, Greater London.[4]

Styles of address

- 1757-1784: Mr Henry Addington

- 1784-1789: Mr Henry Addington MP

- 1789-1805: The Right Honourable Henry Addington MP

- 1805-1844: The Right Honourable The Viscount Sidmouth PC

Henry Addington's Government, March 1801 – May 1804

- Henry Addington – First Lord of the Treasury and Chancellor of the Exchequer

- Lord Eldon – Lord Chancellor

- Lord Chatham – Lord President of the Council and Master-General of the Ordnance

- Lord Westmorland – Lord Privy Seal

- The Duke of Portland – Secretary of State for the Home Department

- Lord Hawkesbury – Secretary of State for Foreign Affairs

- Lord Hobart – Secretary of State for War and the Colonies

- Lord St Vincent – First Lord of the Admiralty

- Lord Liverpool – President of the Board of Trade

Changes

- May 1801 – Lord Lewisham (who becomes Lord Dartmouth in July), the President of the Board of Control, enters the Cabinet

- July 1801 – The Duke of Portland succeeds Lord Chatham as Lord President (Chatham remains Master of the Ordnance). Lord Pelham succeeds Portland as Home Secretary.

- July 1802 – Lord Castlereagh succeeds Lord Dartmouth at the Board of Control.

- August 1803 – Charles Philip Yorke succeeds Lord Pelham as Home Secretary.

See also

References

- ↑ Thomas Goldsmith, "British Diplomatic Attitudes towards Europe, 1801–4: Ignorant and Indifferent?" International History Review (2016) 38#4 pp 657-674.

- ↑ C. D. Hall, "Addington at War: Unspectacular but Not Unsuccessful," Historical Research (1988) 61#146 pp 306-315

- ↑ Michael W. McCahill, "The House of Lords and the Collapse of Henry Addington's Administration," Parliamentary History (1987) 6#1 pp 69-94

- ↑ Henry Addington's short biography in Napoleon & Empire website, displaying a photograph of his tomb

Further reading

- Cookson, J. E. "Addington, Henry, first Viscount Sidmouth (1757–1844)", Oxford Dictionary of National Biography, Oxford University Press, 2004; online edn, May 2009 accessed 29 Dec 2013

- Cookson, J. E. The British armed nation, 1793–1815 (1997) online

- Ehrman, J. The younger Pitt, 3: The consuming struggle (1996)

- Fedorak, Charles John, Henry Addington, Prime Minister, 1801–1804: Peace, War and Parliamentary Politics (Akron, Ohio: University of Akron Press, 2002), 268p.

- Fedorak, C. J. "In search of a necessary ally: Addington, Hawkesbury, and Russia, 1801–1804", International History Review 13 (1991), 221–45

- Kagan, Frederick W. The End of the Old Order: Napoleon and Europe 1801–1805 (2006)

- Ziegler, Philip Addington, A Life of Henry Addington, First Viscount Sidmouth (New York: The John Day Company, 1965), 478p.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Henry Addington, 1st Viscount Sidmouth. |

- "Archival material relating to Henry Addington, 1st Viscount Sidmouth". UK National Archives.

- Henry Addington, Viscount Sidmouth (1757-1844) at David Nash Ford's Royal Berkshire History Website

- Woodley House (Sonning) at David Nash Ford's Royal Berkshire History Website

- Hansard 1803–2005: contributions in Parliament by the Viscount Sidmouth

.svg.png)