Runaway climate change

Runaway climate change or runaway global warming is hypothesized to follow a tipping point in the climate system, after accumulated climate change initiates a reinforcing positive feedback. This is thought to cause the climate to rapidly change until it reaches a new stable condition.[1] These phrases may be used with reference to concerns about rapid global warming.[1][2] Some astronomers use the expression runaway greenhouse effect to describe a situation where the climate deviates catastrophically and permanently from the original state—as happened on Venus.[3][4]

Although these terms are rarely used in the peer-reviewed climatological literature,[5][6] that literature does use the similar phrase "runaway greenhouse effect", which refers specifically to climate changes that cause a planetary body's water to boil off.

Related terms

- At a tipping level or tipping point the climate forcing reaches a point such that no additional forcing is required for large climate change and impacts.[7]

- At a point of no return, climate impacts that are irreversible on a practical time scale occur. An example of such an impact is the disintegration of a large ice sheet.[7]

Runaway greenhouse effect

The runaway greenhouse effect has several meanings. At the least extreme, this implies global warming sufficient to induce out-of-control amplifying feedbacks, such as ice sheet disintegration and melting of methane hydrates. At the most extreme, a Venus-like planet with crustal carbon baked into the atmosphere and a surface temperature of several hundred degrees, an irreversible climate state.

Between these two is the moist greenhouse, which occurs if the climate forcing is large enough to make water vapour (H2O) a major atmospheric constituent.[8] In principle, an extreme moist greenhouse might cause an instability with water vapour preventing radiation to space of all absorbed solar energy, resulting in very high surface temperature and evaporation of the ocean.[9] However, simulations indicate that no plausible human-made greenhouse gas (GHG) forcing can cause an instability and baked-crust runaway greenhouse effect.[10]

Conceivable levels of human-made climate forcing could yield the low-end runaway greenhouse. A forcing of 12–16 W m−2 would require carbon dioxide (CO2) levels to increase 8–16 times. If the forcing were due only to CO2 change, this would raise the global mean temperature by 16–24 °C with much larger polar warming. A warming of 16–24 °C produces a moderately moist greenhouse, with water vapour increasing to about 1% of the atmosphere's mass, thus increasing the rate of hydrogen escape to space. If such a forcing were entirely due to CO2, the weathering process would remove the excess atmospheric CO2 on a time scale of 104–105 years, well before the ocean was significantly depleted. Venus-like conditions on the Earth require a large long-term forcing that is unlikely to occur until the sun brightens by a few tens of percent, which will take a few billion years.[10]

Global habitability

Burning all fossil fuels would adversely affect the ability of humans to live on the planet. If non-CO2 greenhouse gases such as N2O and methane (CH4) were to increase with global warming at the same rate as in the palaeoclimate record and atmospheric chemistry simulations[11] they would provide approximately 25% of the greenhouse forcing. The remaining forcing requires approximately 4.8 times current CO2 levels, corresponding to fossil fuel emissions as much as approximately 10,000 Gt C for a conservative assumption of a CO2 airborne fraction averaging one-third over the 1000 years following a peak emission.[12][13]

Calculated global warming in this case is 16 °C, with warming at the poles approximately 30 °C. Calculated warming over land areas averages approximately 20 °C. Such temperatures would eliminate grain production in almost all agricultural regions in the world.[14] Increased stratospheric water vapour would diminish the stratospheric ozone layer.[15]

Global warming of that magnitude would make most of the planet uninhabitable by humans.[16][17] The human body generates about 100 W of metabolic heat that must be carried away to maintain a core body temperature near 37 °C, which implies that sustained wet bulb temperatures above 35 °C can result in lethal hyperthermia.[16] Today, the summer temperature varies widely over the Earth's surface, but wet bulb temperature is more narrowly confined by the effect of humidity, with the most common value of approximately 26–27 °C and the highest approximately of 31 °C. A warming of 10–12 °C would put most of today's world population in regions with a wetbulb temperature above 35 °C.[16] Given the 20 °C warming that occurs with 4.8 times current CO2 levels, such a climate forcing would produce intolerable climatic conditions even if the true climate sensitivity is significantly less than the Russell sensitivity, or, if the Russell sensitivity is accurate, the CO2 forcing required to produce intolerable conditions for humans is less than this amount.[10]

Feedback effects

The core of the concept of runaway climate change is the idea of a large positive feedback within the climate system. When a change in global temperature causes an event to occur which itself changes global temperature, this is referred to as a feedback effect. If this effect acts in the same direction as the original temperature change, it is a destabilising positive feedback (e.g. warming causing more warming); and if in the opposite direction, it is a stabilising negative feedback (e.g. warming causing a cooling effect). If a sufficiently strong net positive feedback occurs, it is said that a climate tipping point has been passed and the temperature will continue to change until the changed conditions result in negative feedbacks that restabilise the climate.

An example of a negative feedback is that radiation leaving the Earth increases in proportion to the fourth power of temperature, in accordance with the Stefan-Boltzmann law. This feedback is always operational; therefore, while it may be overridden by positive feedbacks for comparatively small temperature changes it will dominate for larger temperature changes. An example of a positive feedback is the ice-albedo feedback, in which increasing temperature causes ice to melt, which increases the amount of heat that Earth absorbs. This feedback only operates in a restricted range of temperatures (those for which ice exists, and does not cover the whole surface; once all the ice has melted, the feedback ceases to operate).

Climate feedback effects can involve positive feedback in a type of forcing, such as the release of methane due to rising methane levels; other greenhouse gases, as when CO2 causes the release of methane; or other variables, such as the ice-albedo feedback.

Without climate feedbacks, a doubling in atmospheric carbon dioxide concentration would result in a global average temperature increase of around 1.2 °C. Water vapor amount and clouds are probably the most important global climate feedbacks. Historical information and global climate models indicate a climate sensitivity of 1.5 to 4.5 °C, with a best estimate of 3 °C. This is an amplification of the carbon dioxide forcing by a factor of 2.5. Some studies suggest a lower climate sensitivity, but other studies indicate a sensitivity above this range. Partly because of the difficulty in modeling the cloud feedback, the true climate sensitivity remains uncertain.[18]

Slow

Slow feedback effects—especially changes in the sizes of ice sheets and levels of atmospheric CO2—amplify the sensitivity of the total Earth system by an amount that depends on the time scale considered.[10]

There are known examples of the Earth's climate producing a large response to small forcings. The CO2 feedback effect is believed to be part of the transition between glacial and interglacial periods, with orbital forcing providing the initial trigger.[19]

A 2006 book chapter by Cox et al. considers the possibility of a future runaway climate feedback due to changes in the land carbon cycle:[20]

Here we use a simple land carbon balance model to analyse the conditions required for a land sink-to-source transition, and address the question; could the land carbon cycle lead to a runaway climate feedback? [...] The simple land carbon balance model has effective parameters representing the sensitivities of climate and photosynthesis to CO2, and the sensitivities of soil respiration and photosynthesis to temperature. This model is used to show that (a) a carbon sink-to-source transition is inevitable beyond some finite critical CO2 concentration provided a few simple conditions are satisfied, (b) the value of the critical CO2 concentration is poorly known due to uncertainties in land carbon cycle parameters and especially in the climate sensitivity to CO2, and (c) that a true runaway land carbon-climate feedback (or linear instability) in the future is unlikely given that the land masses are currently acting as a carbon sink.

Fast

In general, fast feedback climate sensitivity depends on the initial climate state. Fast feedback effects include changes in levels of water vapour and aerosols, as well as changes in cloud cover and the extent of sea ice.[10]

Methane deposits and clathrates

Potentially unstable methane deposits exists in permafrost regions, which are expected to retreat as a result of global warming,[21] and also clathrates, with the clathrate effect probably taking millennia to fully act.[22] The potential role of methane from clathrates in near-future runaway scenarios is not certain, as studies[23] show a slow release of methane, which may not be regarded as 'runaway' by all commentators. The clathrate gun runaway effect may be used to describe more rapid methane releases. Methane in the atmosphere has a high global warming potential, but breaks down relatively quickly to form CO2, which is also a greenhouse gas. Therefore, slow methane release will have the long-term effect of adding CO2 to the atmosphere.

In order to model clathrates and other reservoirs of greenhouse gases and their precursors, global climate models would have to be 'coupled' to a carbon cycle model. Most current global climate models do not include modelling of methane deposits.

Current risk

The scientific consensus in the IPCC Fourth Assessment Report[24] is that "Anthropogenic warming could lead to some effects that are abrupt or irreversible, depending upon the rate and magnitude of the climate change." Note however that this statement is about situations weaker than "runaway change". Text prepared for the IPCC Fifth Assessment Report states that "a 'runaway greenhouse effect'—analogous to Venus—appears to have virtually no chance of being induced by anthropogenic activities."[25]

Estimates of the size of the total carbon reservoir in Arctic permafrost and clathrates vary widely. It is suggested that at least 900 gigatonnes of carbon in permafrost exists worldwide.[26] Furthermore, there are believed to be another 400 gigatonnes of carbon in methane clathrates in permafrost regions [27] with 10,000 to 11,000 gigatonnes worldwide.[27] This is large enough that if 10% of the stored methane were released, it would have an effect equivalent to a factor of 10 increase in atmospheric CO2 concentrations.[28] Methane is a potent greenhouse gas with a higher global warming potential than CO2.

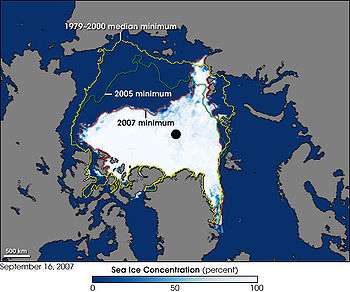

Worries about the release of this methane and carbon dioxide is linked to arctic shrinkage. Recent years have seen record low Arctic sea ice. It has been suggested that rapid melting of the sea ice may initiate a feedback loop that rapidly melts arctic permafrost.[29][30] Methane clathrates on the sea-floor have also been predicted to destabilise, but much more slowly.[27]

A release of methane from clathrates, however, is believed to be slow and chronic rather than catastrophic and that 21st-century effects of such a release are therefore likely to be 'significant but not catastrophic'.[28] It is further noted that 'much methane from dissociated gas hydrate may never reach the atmosphere',[31] as it can be dissolved into the ocean and be broken down biologically.[31] Other research[32] demonstrates that a release to the atmosphere can occur during large releases. These sources suggest that the clathrate gun effect alone will not be sufficient to cause 'catastrophic'[28] climate change within a human lifetime.

Hansen et al. 2013 suggests that the Earth could become in large parts uninhabitable and note that this may not even require burning of all fossil fuels, because of higher climate sensitivity (3–4 °C or 5.4–7.2 °F) based on a 550 ppm scenario. Burning all fossil fuels would warm land areas on average about 20 °C (36 °F) and warm the poles 30 °C (54 °F).[10] Earlier estimates are based on the assumption that fossil-fuel use continues until reserves are exhausted, and predicted a runaway greenhouse effect, a climate similar to that on Venus.[33] Ongoing research determines if such a climate state is possible on Earth.[34][35][36]

Paleoclimatology

Events that could be described as runaway climate change may have occurred in the past.

Clathrate gun

The clathrate gun hypothesis suggests an abrupt climate change due to a massive release of methane gas from methane clathrates on the seafloor. It has been speculated that the Permian-Triassic extinction event[37] and the Paleocene-Eocene Thermal Maximum[38] were caused by massive clathrate release.

Snowball Earth

Geological evidence shows that ice-albedo feedback caused sea ice advance to near the equator at several points in Earth history.[39] Modeling work shows that such an event would indeed be a result of a self-sustaining ice-albedo effect,[40] and that such a condition could be escaped via the accumulation of CO2 from volcanic outgassing.[41]

See also

- Abrupt climate change

- Arctic methane release

- Avoiding dangerous climate change

- Climate change feedback

- Climate sensitivity

References

- 1 2 Brown, Paul (2006-10-18). "How close is runaway climate change?". Guardian.co.uk. Retrieved 2009-05-25.

- ↑ George Monbiot (2008-08-22). "Identity Politics in Climate Change Hell". Monbiot.com.

- ↑ Rasool, I.; De Bergh, C. (Jun 1970). "The Runaway Greenhouse and the Accumulation of CO2 in the Venus Atmosphere" (PDF). Nature. 226 (5250): 1037–1039. Bibcode:1970Natur.226.1037R. doi:10.1038/2261037a0. ISSN 0028-0836. PMID 16057644.

- ↑ Kasting, J. F. (1988). "Runaway and moist greenhouse atmospheres and the evolution of Earth and Venus". Icarus. 74 (3): 472–494. Bibcode:1988Icar...74..472K. doi:10.1016/0019-1035(88)90116-9. PMID 11538226.

- ↑ Doney, S. C.; Schimel, D. S. (2007). "Carbon and Climate System Coupling on Timescales from the Precambrian to the Anthropocene" (PDF). Annual Review of Environment and Resources. 32: 31–63. doi:10.1146/annurev.energy.32.041706.124700.

- ↑ Archer, D.; Buffett, B. (2005). "Time-dependent response of the global ocean clathrate reservoir to climatic and anthropogenic forcing" (PDF). Geochemistry Geophysics Geosystems. 6 (3): Q03002. Bibcode:2005GGG.....603002A. doi:10.1029/2004GC000854.

- 1 2 Hansen, James E. (December 2008). "Climate Threat to the Planet: Implications for Energy Policy and Intergenerational Justice" (PDF). pp. 26–39. Retrieved 2009-02-02.

- ↑ Kasting, JF (1988). "Runaway and moist greenhouse atmospheres and the evolution of Earth and Venus.". Icarus. 74 (3): 472–494. Bibcode:1988Icar...74..472K. doi:10.1016/0019-1035(88)90116-9. PMID 11538226.

- ↑ Ingersoll, AP (1969). "Runaway greenhouse: a history of water on Venus". J. Atmos. Sci. 26: 1191–1198. Bibcode:1969JAtS...26.1191I. doi:10.1175/1520-0469(1969)026<1191:TRGAHO>2.0.CO;2.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 Hansen, James; et al. (September 2013). "Climate sensitivity, sea level and atmospheric carbon dioxide". Royal Society Publishing. 371 (2001): 20120294. doi:10.1098/rsta.2012.0294.

- ↑ Beerling, DJ; Fox A; Stevenson DS; Valdes PJ (2011). "Enhanced chemistry-climate feedbacks in past greenhouse worlds". PNAS. 108 (24): 9770–9775. Bibcode:2011PNAS..108.9770B. doi:10.1073/pnas.1102409108.

- ↑ Archer, D (2005). "Fate of fossil fuel CO2 in geologic time". Journal of Geophysical Research. 110. Bibcode:2005JGRC..110.9S05A. doi:10.1029/2004JC002625.

- ↑ Archer; et al. (2009). "Atmospheric lifetime of fossil fuel carbon dioxide" (PDF). Annu. Rev. Earth Planet. Sci. 37: 117–134. Bibcode:2009AREPS..37..117A. doi:10.1146/annurev.earth.031208.100206.

- ↑ Hatfield; et al. (2011). "Climate impacts on agriculture: implications for crop production". Agron. J. 103: 351–370. doi:10.2134/agronj2010.0303.

- ↑ Anderson; et al. (2012). "UV dosage levels in summer: increased risk of ozone loss from convectively injected water vapor". Science. 337 (6096): 835–839. Bibcode:2012Sci...337..835A. doi:10.1126/science.1222978.

- 1 2 3 Sherwood, SC; Huber M (2010). "An adaptability limit to climate change due to heat stress". PNAS. 107 (21): 9552–9555. Bibcode:2010PNAS..107.9552S. doi:10.1073/pnas.0913352107.

- ↑ McMichael, AJ; Dear KB (2010). "Climate change: heat, health, and longer horizons". PNAS. 107 (21): 9483–9484. Bibcode:2010PNAS..107.9483M. doi:10.1073/pnas.1004894107.

- ↑ Committee on the Science of Climate Change, Division on Earth and Life Studies, National Research Council (2001). "Climate Change Science: An Analysis of Some Key Questions". National Academies Press. pp. 6–7. Retrieved 2009-05-20.

- ↑ Shackleton, N. J. (2000). "The 100,000-Year Ice-Age Cycle Identified and Found to Lag Temperature, Carbon Dioxide, and Orbital Eccentricity". Science. 289 (5486): 1897–1100. Bibcode:2000Sci...289.1897S. doi:10.1126/science.289.5486.1897. PMID 10988063.

- ↑ Cox, P.M., C. Huntingford and C.D. Jones. H.J. Schellnhuber, (ed), W. Cramer, N. Nakicenovic, T. Wigley, and G. Yohe (co-eds) (2006). "Chapter 15: Conditions for Sink-to-Source Transitions and Runaway Feedbacks from the Land Carbon Cycle. In: Avoiding Dangerous Climate Change" (PDF). Cambridge University Press. p. 156. Retrieved 2009-05-20.

- ↑ Lawrence, D. M.; Slater, A. (2005). "A projection of severe near-surface permafrost degradation during the 21st century". Geophysical Research Letters. 32 (24): L24401. Bibcode:2005GeoRL..3224401L. doi:10.1029/2005GL025080.

- ↑ Buffett, B.; Archer, D. (2004). "Global inventory of methane clathrate: sensitivity to changes in the deep ocean" (PDF). Earth and Planetary Science Letters. 227 (3–4): 185–199. Bibcode:2004E&PSL.227..185B. doi:10.1016/j.epsl.2004.09.005.

- ↑ "Gas Escaping From Ocean Floor May Drive Global Warming" (Press release). University of California, Santa Barbara. July 19, 2006.

- ↑ "Summary for Policymakers". Climate Change 2007: Synthesis Report (PDF). IPCC. November 17, 2007.

- ↑ http://www.ipcc.ch/meetings/session31/inf3.pdf

- ↑ "Melting permafrost methane emissions: The other threat to climate change". TerraNature. 2006-09-15.

- 1 2 3 Macdonald, G. J. (1990). "Role of methane clathrates in past and future climates". Climatic Change. 16 (3): 247–243. doi:10.1007/BF00144504.

- 1 2 3 Archer, David (2007). "Methane hydrate stability and anthropogenic climate change" (PDF). Biogeosciences. 4 (4): 521–544. doi:10.5194/bg-4-521-2007. Retrieved 2009-05-25.

- ↑ Lawrence, D. M.; Slater, A. G.; Tomas, R. A.; Holland, M. M.; Deser, C. (2008). "Accelerated Arctic land warming and permafrost degradation during rapid sea ice loss" (PDF). Geophysical Research Letters. 35 (11): L11506. Bibcode:2008GeoRL..3511506L. doi:10.1029/2008GL033985.

- ↑ "Permafrost Threatened by Rapid Retreat of Arctic Sea Ice, NCAR Study Finds" (Press release). UCAR. June 10, 2008. Retrieved 2009-05-25.

- 1 2 Kvenvolden, Keith A. (March 30, 1999). "Potential effects of gas hydrate on human welfare" (PDF). PNAS. 96 (7): 3420–3426. Bibcode:1999PNAS...96.3420K. doi:10.1073/pnas.96.7.3420. PMC 34283

. PMID 10097052. Retrieved 2009-05-23.

. PMID 10097052. Retrieved 2009-05-23. - ↑ De Garidel-Thoron, T.; Beaufort, L.; Bassinot, F.; Henry, P. (Jun 2004). "Evidence for large methane releases to the atmosphere from deep-sea gas-hydrate dissociation during the last glacial episode" (Free full text). Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 101 (25): 9187–9192. Bibcode:2004PNAS..101.9187D. doi:10.1073/pnas.0402909101. ISSN 0027-8424. PMC 438951

. PMID 15197255.

. PMID 15197255. - ↑ Hansen, James (2008-12-17). "Climate Threat to the Planet" (PDF). Retrieved 2009-10-10.

- ↑ Kendall Powell & John Bluck (2002). "Tropical 'runaway greenhouse' provides insight to Venus". NASA Ames Research Center.

- ↑ Fricke, H. C.; Williams, C.; Yavitt, J. B. (2009). "Polar methane production, hothouse climates, and climate change". Fall Meeting. American Geophysical Union. Bibcode:2009AGUFMPP44A..02F.

- ↑ Michael Marshall (2011). "Humans could turn Earth into a hothouse". Elsevier. pp. 10–11. doi:10.1016/S0262-4079(11)62820-0.

- ↑ Benton, M. J.; Twitchet, R. J. (2003). "How to kill (almost) all life: the end-Permian extinction event" (PDF). Trends in Ecology & Evolution. 18 (7): 358–365. doi:10.1016/S0169-5347(03)00093-4.

- ↑ D.J. Lunt; P.J. Valdes; A. Ridgwell. "Sensitivity to CO2 of the Eocene climate: implications for ocean circulation and clathrate destabilisation" (PDF). BRIDGE (Bristol Research Initiative for the Dynamic Global Environment), University of Bristol, UK.

- ↑ Hoffman, P. F.; Kaufman, A. J.; Halverson, G. P.; Schrag, D. P. (1998). "A Neoproterozoic Snowball Earth" (PDF). Science. 281 (5381): 1342–1346. Bibcode:1998Sci...281.1342H. doi:10.1126/science.281.5381.1342. PMID 9721097.

- ↑ M.I. Budyko (1969). "Effect of solar radiation variation on climate of Earth" (PDF). Tellus. 21 (5): 611–1969. doi:10.1111/j.2153-3490.1969.tb00466.x.

- ↑ Kirschvink, Joseph (1992). "Late Proterozoic low-latitude global glaciation: the Snowball Earth". In J. W. Schopf; C. Klein. The Proterozoic Biosphere: A Multidisciplinary Study. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 0-521-36615-1.