5th SS Panzer Division Wiking

| 5th SS Panzer Division Wiking | |

|---|---|

|

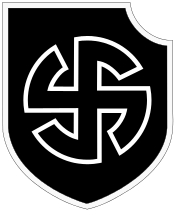

Unit insignia | |

| Active | 1941–45 |

| Country |

|

| Allegiance | Adolf Hitler |

| Branch |

|

| Type | Panzer |

| Role | Armoured warfare |

| Size | Division |

| Engagements | Eastern Front (World War II) |

| Commanders | |

| Notable commanders |

Obergruppenführer Felix Steiner Obergruppenführer Herbert Otto Gille Oberführer Eduard Deisenhofer Standartenführer Johannes Mühlenkamp Oberführer Karl Ullrich |

The 5th SS Panzer Division Wiking was an elite Panzer division among the thirty eight Waffen-SS divisions of Nazi Germany. It was recruited from foreign volunteers in Denmark, Norway, Sweden, Finland, Estonia, the Netherlands and Belgium under the command of German officers. During the course of World War II, the division served on the Eastern Front during World War II. It surrendered in May 1945 to the American forces in Austria.

Formation and training

After the invasion of Poland in 1939, Reichsführer-SS Heinrich Himmler sought to expand the Waffen-SS with foreign military volunteers for the "crusade against Bolshevism". The enrolment began in April 1940 with the creation of two regiments: the Waffen-SS Regiment Nordland (for Danish, Norwegian, and Swedish volunteers), and the Waffen-SS Regiment Westland (for Dutch, and Flemish volunteers).[1]

The Nordic formation, originally organised as the Nordische Division (Nr. 5), was to be made up of Nordic volunteers mixed with ethnic German Waffen-SS personnel. The SS Infantry Regiment Germania of the SS-Verfügungs-Division, which was formed mostly from ethnic Germans, was transferred to help form the nucleus of a new division in late 1940.[2] In December 1940, the new SS motorised formation was to be designated SS-Division (mot.) Germania, but after its formative period, the name was changed, to SS-Division (mot.) Wiking in January 1941.[3] The Wiking division was formed around three motorised infantry regiments: Germania, Westland, and Nordland; with the addition of the SS Artillery Regiment 5. Command of the newly formed division was given to Brigadeführer Felix Steiner, the former commander of the Verfügungstruppe SS Regiment "Deutschland".[4]

After formation the division was sent to Heuberg in Germany for training and by April 1941, SS Division Wiking was ready for combat. It was ordered east in mid-May, to take part with Army Group South's advance into the Ukraine during Operation Barbarossa, the invasion of the Soviet Union.[5] In June 1941 the Finnish Volunteer Battalion of the Waffen-SS was formed from volunteers from that country. After training, this unit was attached to the SS Regiment Nordland of the division. About 430 Finns who fought in the Winter War served within the SS Division Wiking division since the beginning of Operation Barbarossa. In spring 1943, the Finnish battalion was withdrawn. During that same timeframe, the Wiking's SS-Panzergrenadier-Regiment Nordland was removed to help form the core of the new 11th SS Volunteer Panzergrenadier Division Nordland. They were replaced by the Estonian infantry battalion Narwa.[6]

Invasion of the Soviet Union

The division took part in Operation Barbarossa, the invasion of the Soviet Union, advancing through Galicia, Ukraine. In August the division fought for the bridgehead across the Dniepr River. Later, the division took part in the heavy fighting for Rostov-on-Don before retreating to the Mius River line in November. In the summer of 1942, Wiking took part Army Group South's offensive Case Blue, aimed at capturing Stalingrad and the Baku oilfields. In late September 1942, Wiking participated in the operation aimed to capture the city of Grozny, alongside the 13th Panzer Division. The division captured Malgobek on 6 October, but the objective of seizing Grozny and opening a road to the Caspian Sea was not achieved. The division took part in the attempt to seize Ordzhonikidze. The Soviet Operation Uranus, the encirclement of the 6th Army at Stalingrad, brought any further advances in the Caucasus to a halt.

After Operation Winter Storm, the failed attempt to relieve the 6th Army, Erich von Manstein, the commander of Army Group South, proposed another attempt towards Stalingrad. To that end, Wiking entrained on 24 December; however, by the time it arrived on 31 December, it was forced to cover the withdrawal of Army Group A from the Caucasus towards Rostov. The division escaped through the Rostov gap on 4 February.

1943–1945

In early 1943, the Wiking fell back to Ukraine south of Kharkov, recently abandoned by the II SS Panzer Corps commanded by Paul Hausser. In the remaining weeks of February, the Corps, including Wiking, engaged Mobile Group Popov, the major Soviet armoured force named after Markian Popov during the Third Battle of Kharkov. The losses of Popov's Group halted the Soviet offensive which followed the Battle of Stalingrad and stabilized Manstein's front.

In 1943, Herbert Gille was appointed to command the division. The SS Regiment Nordland, along with its commander Fritz von Scholz, were removed from the division and used as the nucleus for the new 11th SS Volunteer Panzergrenadier Division Nordland. The Finnish Volunteer Battalion was also withdrawn and they were replaced by the Estonian infantry battalion Narwa.[7]

In the summer of 1943, along with the 23rd Panzer Division, formed the reserve force for Manstein's Army Group for Operation Citadel. Immediately following the German failure in the Battle of Kursk, the Red Army launched counter-offensives, Operation Kutuzov and Operation Rumyantsev. Wiking, together with SS Division Totenkopf and the SS Division Das Reich, was sent to the Mius-Bogodukhov sector. The Soviets took Kharkov on 23 August and began advancing towards the Dnieper. In October the division was pulled out of the line.

On 13 February 1945, Wiking was ordered west to Lake Balaton, where Oberstgruppenführer Sepp Dietrich's 6th SS Panzer Army was preparing for the Lake Balaton Offensive known as Operation Spring Awakening.[8] After the failure of Konrad III, Wiking retreated into Czechoslovakia. Gille's remained as a support to the 6th SS Panzer Army during the beginning of the operation. Dietrich's army made "good progress" at first, but as they drew near the Danube, the combination of the muddy terrain and strong Soviet resistance ground them to a halt.[9] Wiking performed a holding operation on the left flank of the offensive, in the area between Lake Velence-Székesfehérvár. As the operation progressed, the division was engaged in preventing Soviet efforts at outflanking the advancing German forces. On 16 March, the Soviets forces counterattacked in overwhelming strength causing the Germans to be driven back to their starting positions.[10] On 24 March, another Soviet attack threw the IV SS Panzer Corps back towards Vienna; all contact was lost with the neighbouring I SS Panzer Corps, and any resemblance of an organised line of defence was gone. Wiking withdrew into Czechoslovakia. The division surrendered to the American forces near Fürstenfeld, Austria on 9 May.

War crimes

Following the shooting death of Hilmar Wäckerle, one of the division's officers, in Lvov, Ukrainian Jews in the area were rounded up by members of the Wiking division's bakery column led by Obersturmführer Braunnagel and Untersturmführer Kochalty. A gauntlet was then formed by two rows of soldiers. Most of these soldiers were from the meat train and the baking company, but some were members of the German 1st Mountain Division. The Jews were then forced to run down this path while being struck by rifle butts and bayonets. At the end of this path stood a number of SS and army officers that shot the Jews as soon as they entered the bomb crater being used as a mass grave. About 50 or 60 Jews were killed in this manner.[11]

In addition historian Eleonore Lappin from the Institute for the History of Jews in Austria, has documented several cases of war crimes committed by members of Wiking in her work The Death Marches of Hungarian Jews Through Austria in the Spring of 1945.[12]

On 28 March 1945, 80 Jews from an evacuation column, although fit for the journey, were shot by three members of Wiking and five military policemen. On 4 April, 20 members of another column that left Graz tried to escape near the town of Eggenfeld, not far from Gratkorn. Soldiers from Wiking that were temporarily stationed there apprehended them in the forest near Mt. Eggenfeld and then herded them into a gully, where they were shot. On 7–11 April 1945, members of the division executed another eighteen escaped prisoners.[12]

Modern reports

In 2013 the NRK quoted "the first Norwegian [to publicly admit] that he participated in war crimes and extermination of Jews in Eastern Europe"[13] during World War II, former soldier of the division, Olav Tuff, who admitted: "In one instance in Ukraine during the autumn of 1941, civilians were herded like cattle—into a church. Shortly afterwards soldiers from my unit started to pour gasoline onto the church and somewhere between 200 and 300 humans were burned inside [the church]. I was assigned as guard, and no one came out."[13]

The 2014 Norwegian book Morfar, Hitler og jeg (Grandfather, Hitler and I) quotes the diary of a division soldier from 1941-1943: "and then we cleaned a Jew hole".[14]

Josef Mengele

The notorious Dr. Josef Mengele, served with the SS Division Wiking during its early campaigns. He served as a combat medic and was awarded the Iron Cross for saving two wounded men from a tank. After being wounded himself, Mengele was deemed unfit for combat and was absorbed into the SS Nazi concentration camp system. Mengele was proud of his Waffen-SS service and his front-line decorations. As the horrors of his crimes came to light, former personnel of the division attempted to have his name removed from its rolls.[15]

Commanders

- SS-Obergruppenführer Felix Steiner (1 December 1940 – 1 May 1943)

- SS-Gruppenführer Herbert Otto Gille (1 May 1943 – 6 August 1944)

- SS-Standartenführer Eduard Deisenhofer (6 August 1944 – 12 August 1944)

- SS-Standartenführer Johannes Mühlenkamp (12 August 1944 – 9 October 1944)

- SS-Oberführer Karl Ullrich (9 October 1944 – 5 May 1945)

See also

- List of Knight's Cross Recipients 5th SS Panzer Division Wiking

- Battle of Jaworów – the final battle of SS Germania regiment

- Waffen-SS in popular culture

References

Citations

- ↑ McNab, pp. 167, 178

- ↑ McNab, p. 167

- ↑ Stein, pp. 103, 104

- ↑ Stein, p. 103

- ↑ McNab, p. 178

- ↑ Littlejohn (1987) p. 53.

- ↑ Littlejohn (1987) p. 53.

- ↑ Stein (1984) p. 238.

- ↑ Stein (1984) p. 238.

- ↑ Dollinger (1967) p. 182.

- ↑ Rhodes, Richard (2003). Masters of Death: The SS-Einsatzgruppen and the Invention of the Holocaust. p. 63, Vintage.

- 1 2 Lappin

- 1 2 Olav Tuff (91): Vi brente en kirke med sivilister

- ↑ Ei ny fortid [A new past] "Bestefaren Per Pedersen Tjøstland var frontkjempar i 5. SS Panzer-divisjon Wiking frå 1941–1943, og skreiv for bladet Germaneren. Hans eigne dagbøker og artiklar er ei hovudkjelde, men Jackson skriv at det er umulig å vite nøyaktig kva han var med på. Kanskje seier det sitt at han bruker uttrykket «så rensket vi et jødehull»"

- ↑ Clifton

Bibliography

- Clifton, Robert J (1985). "What made this man Mengele". The New York Times Company. Archived from the original on 18 April 2009. Retrieved 2009-03-29.

- Dollinger, Hans (1967) [1965]. The Decline and Fall of Nazi Germany and Imperial Japan. New York: Bonanza. ISBN 978-0-517-01313-7.

- Lappin, Eleonore. "The death marches of Hungarian Jews through Austria" (PDF). yadvashem. Archived (PDF) from the original on 19 February 2009. Retrieved 2009-03-28. pp. 25–26

- Littlejohn, David (1987). Foreign Legions of the Third Reich Vol. 1 Norway, Denmark, France. Bender Publishing. ISBN 978-0912138176.

- McNab, Chris (2013). Hitler's Elite: The SS 1939-45. Osprey Publishing. ISBN 978-1782000884.

- Stein, George H (1984). The Waffen SS: Hitler's Elite Guard at War, 1939–1945. Cornell University Press. ISBN 0-8014-9275-0.

- Struve, Kai (2015). Deutsche Herrschaft, ukrainischer Nationalismus, antijüdische Gewalt [German Rule, Ukrainian Nationalism, and Anti-Semitic Violence: The Summer of 1941 in Western Ukraine] (in German). Berlin, Germany: De Gruyter Oldenbourg. ISBN 9783110359985.