Cheraw

|

| |

| Total population | |

|---|---|

| (Extinct as a tribe[1]) | |

| Regions with significant populations | |

|

| |

| Languages | |

| Siouan language | |

| Religion | |

| Tribal colonies | |

| Related ethnic groups | |

|

Catawba, Saponi, Waccamaw, and other Siouan peoples |

The Cheraw people, also known as the Saraw or Saura,[1] were a Siouan-speaking tribe of indigenous people of the Southeastern Woodlands,[1] in the Piedmont area of North Carolina near the Sauratown Mountains, east of Pilot Mountain and north of the Yadkin River. They lived in villages near the Catawba River.[2] Their first European and African contact was with the Hernando De Soto Expedition in 1540. The early explorer John Lawson included them in the larger eastern-Siouan confederacy, which he called "the Esaw Nation."[3]

After attacks in the late 17th century and early 18th century, they moved to the southeast around the Pee Dee River, where the Cheraw name became more widely used. They became extinct as a tribe, although some descendants survived as remnant peoples.

Name

Originally known as the Saraw, they became known by the name of one of their villages, Cheraw.[4] They are also known as the Charáh, Charrows, Charra, Charaws, Charraws, Chara,[5] Sara, Saura, Suali, Sualy, Xualla, and Xuala. The name they called themselves is lost to history but the Cherokee called them Ani-suwa'ii and the Catawba Sara ("place of tall weeds"). The Spanish and Portuguese called their territory Xuala (or Xualla).

The early English records of South Carolina refer to the Saura, spelled "Saraw", a few times.

Territory

Cheraw (Saura, Xualae) were reported in various parts of South Carolina, North Carolina, Virginia and West Virginia. In the early 18th century, the Cheraw lived in present-day Chesterfield County in northeastern South Carolina. This region, which now encompasses present day Chesterfield, Marlboro, Darlington, and parts of Lancaster counties, was known later in the 18th and 19th centuries as "The Cheraws", the "Cheraw Hills", and later the "Old Cheraws." Their main village was near the site of present-day Cheraw, close to the North Carolina border. Cheraw was one of the earliest inland towns which European Americans established in South Carolina.

History

Origins

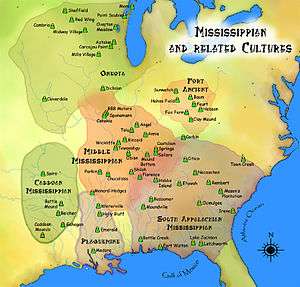

Scholars have conflicting theories about the tribe, its history, and its relation to other tribes. Some sources say the Cheraw are descended from the Mississippian culture chiefdom of Joara, located in present-day western North Carolina. In the mid-16th century, the Juan Pardo Expedition founded the short-lived Fort San Juan in Joara.

16th century

Few historical references to the Cheraw exist. Spanish explorer De Soto may have passed through Cheraw towns in the mountains near present-day Asheville and Henderson, Polk, and Rutherford counties in North Carolina in 1540. Their villages were adjacent to those of the Pedee and Catawba peoples.[2]

17th century

In 1600, they may have numbered 1,200. In 1670, they left their homes near present-day Asheville to settle on the lower Yadkin River, then the Dan River in Rockingham County.[2] By 1672, they may have moved to the Stokes County region, near the Saura Mountains.

In 1670, German explorer John Lederer, departing from Fort Henry in Virginia Colony, explored deep into North Carolina and described a large town he called "Sara", in the mountains that "receive from the Spaniards the name of Suala". He wrote that the natives here mined cinnabar to make purple facepaint, and had cakes of salt. James Needham and Gabriel Archer also explored the entire area from Fort Henry in 1671, and described this town as "Sarrah."

18th century

In 1710, due to attacks by the Seneca[6] of the Iroquois Confederacy (Haudenosaunee) from the north (whose empire by then extended along the colonial frontier northward, with hunting grounds in the Ohio River valley and the St. Lawrence River valley), the Cheraw moved southeast and joined the Keyauwee tribe. The Saura Indian villages, one known as Lower Sauratown and the other, Upper Sauratown, were at that time abandoned. Lower Sauratown was situated below the present town of Eden, near the mouth of Town Creek in northeastern Rockingham County, North Carolina, while Upper Sauratown was located in Stokes County, N.C.

The Saura nation were recorded in The Journal of Barnwell as maintaining a village on the east bank of the upper branches of the Pee Dee River circa the Tuscarora War in 1712.[3] Some Cheraw fought with South Carolina in the Tuscarora War.

In 1712, John Barnwell led a force of 400-500 troops against the Tuscarora in North Carolina. Almost all his forces were Indians, organized into four companies, based in part on tribal and cultural factors. The 1st and 2nd companies were made up of Indians with strong ties to South Carolina. The 3rd company was of "northern Indians" who lived farther from Charles Town and whose allegiance was not as strong. They included the Catawba, Waxaw, Wateree, and Congaree, among others.

The 4th company was of northern Indians who lived even farther away and whose allegiance was still weaker. Among this group were the Saraw, Saxapahaw, Peedee, Cape Fear, Hoopengs, and others. This 4th company was noted for high levels of desertion.

Historian Alan Gallay has speculated that the Saura and Saxapahaw people deserted Barnwell's army because their villages were likely to be attacked by the Tuscarora in vengeance for assisting South Carolina in the war.[7] Gallay described the approximate location of the Saura homeland as "about 60 miles upriver from the Peedees", whose home is described as "on the Peedee River about 80 miles west of the coast". This puts the Saura in the general vicinity of the upper Dan and Yadkin rivers.[7]

In 1715, Cheraw warriors joined other Southeastern tribes in the Yamasee War to fight against European enslavement of Indians, mistreatment, and encroachment on their territory. On July 18, 1715, a Cheraw delegation represented the Catawban tribes in Williamsburg, Virginia and negotiated peace. They were out of the war by October of 1715.[8]

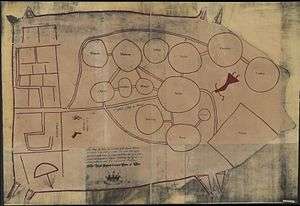

In 1728, William Byrd conducted an expedition to survey the North Carolina and Virginia boundary, and reported finding two Saura villages on the Dan River, known as Lower Saura Town and Upper Saura Town. The towns had been abandoned by the time of Byrd's visit. He noted in his writing that the Saura had been attacked and nearly destroyed by the Seneca 30 years before, who had been raiding peoples on the frontier from their base in present-day New York. The Saura were known to have moved south to the Pee Dee River area.

When the Council of Virginia offered tribes protection in 1732, the Cheraw asked to join the Saponis.[4] In 1738, a smallpox epidemic decimated both the Cheraw and the Catawba. In 1755, the Cheraw were persuaded by South Carolina Governor James Glen to join the Waccamaw, Pedee, and Catawba, led by King Haigler.[9] The remnants of the tribes combined. Some of the tribe may have moved north and founded the "Charraw Settlement" along Drowning Creek, (present-day Robeson County) North Carolina.[3] The tribe was mostly destroyed before the middle of the 18th century and European encroachment on their old territory.

By 1754, racially mixed families lived along the Lumber River. Cheraw women with the surname Grooms married into this group, which later became known as the Lumbee people.[10]

They were last noted as a distinct tribe among the Catawba in 1768. During the Revolutionary War, they and the Catawba removed their families to the same areas near Danville, Virginia, where they had lived earlier. Their warriors served the Patriot cause under General Thomas Sumter.[3]

Population

In 1715, South Carolinian John Barnwell conducted a census of Indians in the region. The Saraw were grouped with the "northern" or "Piedmont" peoples. This group had relatively fewer ties to South Carolina and were not counted as accurately as were the Muscogee, Cherokee, Yamasee, and others. Other "northern" Piedmont peoples named in the 1715 census include the Catawba, Waccamaw, Santee Congaree, Wereaw, and others. The Saraw are listed as living in one village with a population of 510, of which 140 were men and 370 were women and children. South Carolina probably acquired these numbers at least partially through second-hand sources and estimates.

In 1768, Cheraw numbered only 50–60 individuals

Descendants

In 1835, Cheraw descendants, who had been absorbed into the Catawba tribe,[11] were classified as "free people of color" in local records. Today the state-recognized Lumbee Indians of Robeson County, North Carolina, and the Sumter Band of Cheraw Indians[12] of Sumter County, South Carolina, claim descent from the Cheraw.

Namesakes

Cheraw, South Carolina, is named for the tribe. Cheraw, Colorado, was named by an early settler who was born in Cheraw, South Carolina, and migrated west.

Located in Walnut Cove, North Carolina, South Stokes High School's team mascot name honors the Native American Indian Saura tribe.

See also

References

Citations

- 1 2 3 Sebeok, Thomas Albert. Native Languages of the Americas, Volume 2. Plenum Press, 1977: 251.

- 1 2 3 Rudes et al. 310

- 1 2 3 4 Handbook of the American Indian North of Mexico, 1906

- 1 2 Demallie 296

- ↑ Rules 316

- ↑ Beck, p. 170 Quote: "William Byrd of Westover, writing in 1733, similarly reports that 'the frequent inroads of the Senecas' (1928:290) had forced the Saras, probably descendants of Joara, to leave the Dan for the Pee Dee some thirty years before..."

- 1 2 Gallay, Alan. The Indian Slave Trade: The Rise of the English Empire in the American South 1670-1717. Yale University Press, New Haven, 2002.

- ↑ Rudes et al. 309

- ↑ Rudes et al. 311

- ↑ Blu 319

- ↑ Blu 320

- ↑ "Cheraw Indians chief to speak at Genealogical Society". Theitem. February 10, 2013.

BIbliography

- Beck, Robin. Chiefdoms, Collapse, and Coalescence in the Early American South, Cambridge University Press, 2013, p. 170

- Blu, Karen I. "Lumbee." In Handbook of North American Indians: Volume 14, Southeast. Washington, DC: Smithsonian Institution, 2004. ISBN 0-16-072300-0.

- Demallie, Raymond J. "Tutelo and Neighboring Groups." In Handbook of North American Indians: Volume 14, Southeast. Washington, DC: Smithsonian Institution, 2004. ISBN 0-16-072300-0.

- Gallay, Alan. The Indian Slave Trade: The Rise of the English Empire in the American South 1670-1717. Yale University Press, New Haven, 2002. ISBN 0-300-10193-7

- Rudes, Blair A., Thomas J. Blumer, and J. Alan May. "Catawba and Neighboring Groups." In Handbook of North American Indians: Volume 14, Southeast. Washington, DC: Smithsonian Institution, 2004. ISBN 0-16-072300-0.

External links

- "Handbook of North American Indians: North Carolina Indian Tribes". Smithsonian Institution, carried on Access Genealogy, Indian Tribal Records. 1906. Retrieved 2007-05-24.

- "South Carolina Indians: Cheraw". SCIway. Retrieved 2007-05-24.

- "Sumter Tribe of Cheraw Indians". The Sumter Tribe of Cheraw Indians. Retrieved 2014-12-06.

- 1905 Reprint of Bishop Gregg's History of the Old Cheraws (pdf)

- Stokes County, North Carolina

- History of Saura Indians