Security-Enhanced Linux

|

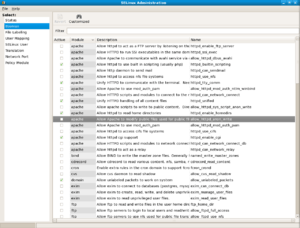

SELinux administrator GUI in Fedora 8 | |

| Original author(s) | NSA and Red Hat |

|---|---|

| Developer(s) | Red Hat |

| Initial release | January 1, 1998 |

| Stable release |

2.5

/ 23 February 2016[1] |

| Repository |

github |

| Written in | C |

| Operating system | Linux |

| Type | Security, Linux Security Modules (LSM) |

| License | GNU GPL |

| Website |

selinuxproject |

Security-Enhanced Linux (SELinux) is a Linux kernel security module that provides a mechanism for supporting access control security policies, including United States Department of Defense–style mandatory access controls (MAC).

SELinux is a set of kernel modifications and user-space tools that have been added to various Linux distributions. Its architecture strives to separate enforcement of security decisions from the security policy itself and streamlines the volume of software charged with security policy enforcement.[2][3] The key concepts underlying SELinux can be traced to several earlier projects by the United States National Security Agency (NSA).

Overview

From NSA Security-enhanced Linux Team:[4]

NSA Security-enhanced Linux is a set of patches to the Linux kernel and some utilities to incorporate a strong, flexible mandatory access control (MAC) architecture into the major subsystems of the kernel. It provides an enhanced mechanism to enforce the separation of information based on confidentiality and integrity requirements, which allows threats of tampering and bypassing of application security mechanisms to be addressed and enables the confinement of damage that can be caused by malicious or flawed applications. It includes a set of sample security policy configuration files designed to meet common, general-purpose security goals.

A Linux kernel integrating SELinux enforces mandatory access control policies that confine user programs' and system servers' access to files and network resources. Limiting privilege to the minimum required to work reduces or eliminates the ability of these programs and daemons to cause harm if faulty or compromised (via buffer overflows or misconfigurations, for example). This confinement mechanism operates independently of the traditional Linux (discretionary) access control mechanisms. It has no concept of a "root" super-user, and does not share the well-known shortcomings of the traditional Linux security mechanisms (such as a dependence on setuid/setgid binaries).

The security of an "unmodified" Linux system (a system without SELinux) depends on the correctness of the kernel, of all the privileged applications, and of each of their configurations. A problem in any one of these areas may allow the compromise of the entire system. In contrast, the security of a "modified" system (based on an SELinux kernel) depends primarily on the correctness of the kernel and its security-policy configuration. While problems with the correctness or configuration of applications may allow the limited compromise of individual user programs and system daemons, they do not necessarily pose a threat to the security of other user programs and system daemons or to the security of the system as a whole.

From a purist perspective, SELinux provides a hybrid of concepts and capabilities drawn from mandatory access controls, mandatory integrity controls, role-based access control (RBAC), and type enforcement architecture. Third-party tools enable one to build a variety of security policies.

History

The earliest work directed toward standardizing an approach toward provision of mandatory and discretionary access controls (MAC and DAC) within a UNIX (more precisely, POSIX) computing environment can be attributed to the National Security Agency's Trusted UNIX (TRUSIX) Working Group, which met from 1987 to 1991 and published one Rainbow Book (#020A), and produced a formal model and associated evaluation evidence prototype (#020B) that was ultimately unpublished.

SELinux was designed to demonstrate the value of mandatory access controls to the Linux community and how such controls could be added to Linux. Originally, the patches that make up SELinux had to be explicitly applied to the Linux kernel source; SELinux has been merged into the Linux kernel mainline in the 2.6 series of the Linux kernel.

The NSA, the original primary developer of SELinux, released the first version to the open source development community under the GNU GPL on December 22, 2000.[5] The software merged into the mainline Linux kernel 2.6.0-test3, released on 8 August 2003. Other significant contributors include Red Hat, Network Associates, Secure Computing Corporation, Tresys Technology, and Trusted Computer Solutions. Experimental ports of the FLASK/TE implementation have been made available via the TrustedBSD Project for the FreeBSD and Darwin operating systems.

Security-Enhanced Linux implements the Flux Advanced Security Kernel (FLASK). Such a kernel contains architectural components prototyped in the Fluke operating system. These provide general support for enforcing many kinds of mandatory access control policies, including those based on the concepts of type enforcement, role-based access control, and multilevel security. FLASK, in turn, was based on DTOS, a Mach-derived Distributed Trusted Operating System, as well as Trusted Mach, a research project from Trusted Information Systems that had an influence on the design and implementation of DTOS.

Users, policies and security contexts

SELinux users and roles do not have to be related to the actual system users and roles. For every current user or process, SELinux assigns a three string context consisting of a username, role, and domain (or type). This system is more flexible than normally required: as a rule, most of the real users share the same SELinux username, and all access control is managed through the third tag, the domain. The circumstances under which a process is allowed into a certain domain must be configured in the policies. The command runcon allows for the launching of a process into an explicitly specified context (user, role and domain), but SELinux may deny the transition if it is not approved by the policy.

Files, network ports, and other hardware also have an SELinux context, consisting of a name, role (seldom used), and type. In case of file systems, mapping between files and the security contexts is called labeling. The labeling is defined in policy files but can also be manually adjusted without changing the policies. Hardware types are quite detailed, for instance, bin_t (all files in the folder /bin) or postgresql_port_t (PostgreSQL port, 5432). The SELinux context for a remote file system can be specified explicitly at mount time.

SELinux adds the -Z switch to the shell commands ls, ps, and some others, allowing the security context of the files or process to be seen.

Typical policy rules consist of explicit permissions; which domains the user must possess to perform certain actions with the given target (read, execute, or, in case of network port, bind or connect), and so on. More complex mappings are also possible, involving roles and security levels.

A typical policy consists of a mapping (labeling) file, a rule file, and an interface file, that define the domain transition. These three files must be compiled together with the SELinux tools to produce a single policy file. The resulting policy file can be loaded into the kernel, making it active. Loading and unloading policies does not require a reboot. The policy files are either hand written or can be generated from the more user friendly SELinux management tool. They are normally tested in permissive mode first, where violations are logged but allowed. The audit2allow tool can be used later to produce additional rules that extend the policy to allow all legitimate activities of the application being confined.

Features

SELinux features include:

- clean separation of policy from enforcement

- well-defined policy interfaces

- support for applications querying the policy and enforcing access control (for example, crond running jobs in the correct context)

- independence of specific policies and policy languages

- independence of specific security-label formats and contents

- individual labels and controls for kernel objects and services

- support for policy changes

- separate measures for protecting system integrity (domain-type) and data confidentiality (multilevel security)

- flexible policy

- controls over process initialization and inheritance and program execution

- controls over file systems, directories, files, and open file descriptors

- controls over sockets, messages, and network interfaces

- controls over the use of "capabilities"

- cached information on access-decisions via the Access Vector Cache (AVC)[6]

Implementations

SELinux is available with commercial support as part of Red Hat Enterprise Linux (RHEL) version 4 and all future releases. This presence is also reflected in corresponding versions of CentOS and Scientific Linux. The supported policy in RHEL4 is the targeted policy which aims for maximum ease of use and thus is not as restrictive as it might be. Future versions of RHEL are planned to have more targets in the targeted policy which will mean more restrictive policies. SELinux has been implemented in Android since version 4.3[7]

In free community supported GNU/Linux distributions, Fedora was one of the earliest adopters, including support for it by default since Fedora Core 2. Other distributions include support for it such as Debian as of the etch release[8] and Ubuntu as of 8.04 Hardy Heron.[9] As of version 11.1, openSUSE contains SELinux "basic enablement".[10] SUSE Linux Enterprise 11 features SELinux as a "technology preview".[11]

Use scenarios

SELinux can potentially control which activities a system allows each user, process and daemon, with very precise specifications. However, it is mostly used to confine daemons like database engines or web servers that have more clearly defined data access and activity rights. This limits potential harm from a confined daemon that becomes compromised. Ordinary user-processes often run in the unconfined domain, not restricted by SELinux but still restricted by the classic Linux access rights.

Command-line utilities include:[12]

chcon,[13]

restorecon,[14]

restorecond,[15]

runcon,[16]

secon,[17]

fixfiles,[18]

setfiles,[19]

load_policy,[20]

booleans,[21]

getsebool,[22]

setsebool,[23]

togglesebool[24]

setenforce,

semodule,

postfix-nochroot,

check-selinux-installation,

semodule_package,

checkmodule,

selinux-config-enforcing,[25]

selinuxenabled,[26]

and selinux-policy-upgrade[27]

Examples

To put SELinux into enforcing mode:

$ sudo setenforce 1

To query the SELinux status:

$ getenforce

Comparison with AppArmor

SELinux represents one of several possible approaches to the problem of restricting the actions that installed software can take. Another popular alternative is called AppArmor and is available on SUSE Linux Enterprise Server (SLES), openSUSE and Ubuntu platforms. AppArmor was developed as a component to the now-defunct Immunix Linux platform. Because AppArmor and SELinux differ radically from one another, they form distinct alternatives for software control. Whereas SELinux re-invents certain concepts in order to provide access to a more expressive set of policy choices, AppArmor was designed to be simple by extending the same administrative semantics used for DAC up to the mandatory access control level.

There are several key differences:

- One important difference is that AppArmor identifies file system objects by path name instead of inode. This means that, for example, a file that is inaccessible may become accessible under AppArmor when a hard link is created to it, while SELinux would deny access through the newly created hard link.

- As a result, AppArmor can be said not to be a type enforcement system, as files are not assigned a type; instead, they are merely referenced in a configuration file.

- SELinux and AppArmor also differ significantly in how they are administered and how they integrate into the system.[28]

- Since it endeavors to recreate traditional DAC controls with MAC-level enforcement, AppArmor's set of operations is also considerably smaller than those available under most SELinux implementations. For example, AppArmor's set of operations consist of: read, write, append, execute, lock, and link.[29] Most SELinux implentations will support numbers of operations orders of magnitude more than that. For example, SELinux will usually support those same permissions, but also includes controls for mknod, binding to network sockets, implicit use of POSIX capabilities, loading and unloading kernel modules, various means of accessing shared memory, etc.

- There are no controls in AppArmor for categorically bounding POSIX capabilities. Since the current implementation of capabilities contains no notion of a subject for the operation (only the actor and the operation itself) it is usually the job of the MAC layer to prevent privileged operations on files outside the actor's enforced realm of control (i.e. "Sandbox"). AppArmor can prevent its own policy from being altered, and prevent filesystems from being mounted/unmounted, but does nothing to prevent users from stepping outside their approved realms of control.

- For example, it may be deemed beneficial for help desk employees to change ownership or permissions on certain files even if they don't own them (for example, on a departmental file share). You obviously don't want to give the user(s) root on the box so you give them

CAP_FOWNERorCAP_DAC_OVERRIDE. Under SELinux you (or your platform vendor) can configure SELinux to deny all capabilities to otherwise unconfined users, then create confined domains for the employee to be able to transition into after logging in, one that can exercise those capabilities, but only upon files of the appropriate type.

- For example, it may be deemed beneficial for help desk employees to change ownership or permissions on certain files even if they don't own them (for example, on a departmental file share). You obviously don't want to give the user(s) root on the box so you give them

- There is no notion of multi-level security with AppArmor, thus there is no hard BLP or Biba enforcement available.

- AppArmor configuration is done using solely regular flat files. SELinux (by default in most implementations) uses a combination of flat files (used by administrators and developers to write human readable policy before it's compiled) and extended attributes.

- SELinux supports the concept of a "remote policy server" (configurable via /etc/selinux/semanage.conf) as an alternative source for policy configuration. Central management of AppArmor is usually complicated considerably since administrators must decide between configuration deployment tools being run as root (to allow policy updates) or configured manually on each server.

Similar systems

Isolation of processes can also be accomplished by mechanisms like virtualization; the OLPC project, for example, in its first implementation[30] sandboxed individual applications in lightweight Vservers. Also, the NSA has adopted some of the SELinux concepts in Security-Enhanced Android.[31]

See also

References

- ↑ Lawrence, Steve (2016-02-23). "Release 2016-02-23". selinux. SELinux Project. Retrieved 2016-02-24.

- ↑ "SELinux Frequently Asked Questions (FAQ) - NSA/CSS". National Security Agency. Retrieved 2013-02-06.

- ↑ Loscocco, Peter; Smalley, Stephen (February 2001). "Integrating Flexible Support for Security Policies into the Linux Operating System" (PDF).

- ↑ "Security-Enhanced Linux - NSA/CSS". National Security Agency. 2009-01-15. Retrieved 2013-02-06.

- ↑ Compare

"National Security Agency Shares Security Enhancements to Linux". NSA Press Release. Fort George G. Meade, Maryland: National Security Agency Central Security Service. 2001-01-02. Retrieved 2011-11-17.

The NSA is pleased to announce that it has developed, and is making available to the public, a prototype version of a security-enhanced Linux system.

- ↑ Fedora Documentation Project (2010). Fedora 13 Security-Enhanced Linux User Guide. Fultus Corporation. p. 18. ISBN 978-1-59682-215-3. Retrieved 2012-02-22.

SELinux decisions, such as allowing or disallowing access, are cached. This cache is known as the Access Vector Cache (AVC). Caching decisions decreases how often SELinux rules need to checked, which increases performance.

- ↑ "Security-Enhanced Linux in Android". Android Open Source Project. Retrieved 2016-01-31.

- ↑ "SELinux". debian.org.

- ↑ "How To Install SELinux on Ubuntu 8.04 "Hardy Heron"". Ubuntu Tutorials.

- ↑ "openSUSE News". openSUSE News.

- ↑ "Release Notes for SUSE Linux Enterprise Desktop 11". Novell. Retrieved 2013-02-06.

- ↑ "SELinux/Commands - FedoraProject". Retrieved 2015-11-25.

- ↑ "chcon". Linuxcommand.org. Retrieved 2013-02-06.

- ↑ "restorecon(8) - Linux man page". Linux.die.net. Retrieved 2013-02-06.

- ↑ "restorecond(8) - Linux man page". Linux.die.net. Retrieved 2013-02-06.

- ↑ "runcon(1) - Linux man page". Linux.die.net. Retrieved 2013-02-06.

- ↑ "secon(1) - Linux man page". Linux.die.net. Retrieved 2013-02-06.

- ↑ "fixfiles(8): fix file SELinux security contexts - Linux man page". Linux.die.net. Retrieved 2013-02-06.

- ↑ "setfiles(8): set file SELinux security contexts - Linux man page". Linux.die.net. Retrieved 2013-02-06.

- ↑ "load_policy(8) - Linux man page". Linux.die.net. Retrieved 2013-02-06.

- ↑ "booleans(8) - Linux man page". Linux.die.net. Retrieved 2013-02-06.

- ↑ "getsebool(8): SELinux boolean value - Linux man page". Linux.die.net. Retrieved 2013-02-06.

- ↑ "setsebool(8): set SELinux boolean value - Linux man page". Linux.die.net. Retrieved 2013-02-06.

- ↑ "togglesebool(8) - Linux man page". Linux.die.net. Retrieved 2013-02-06.

- ↑ "Ubuntu Manpage: selinux-config-enforcing - change /etc/selinux/config to set enforcing". Canonical Ltd. Retrieved 2013-02-06.

- ↑ "Ubuntu Manpage: selinuxenabled - tool to be used within shell scripts to determine if". Canonical Ltd. Retrieved 2013-02-06.

- ↑ "Ubuntu Manpage: selinux-policy-upgrade - upgrade the modules in the SE Linux policy". Canonical Ltd. Retrieved 2013-02-06.

- ↑ "SELinux backgrounds". SELinux. Security Guide. SUSE.

- ↑ "apparmor.d - syntax of security profiles for AppArmor".

- ↑ "Rainbow". laptop.org.

- ↑ "SELinux Related Work". NSA.gov.

External links

- Official website

- NSA:

- Security-Enhanced Linux at NSA

- Mailing list

- "NSA shares security enhancements to Linux". Press release. Jan 2, 2001.

- SELinux on GitHub

- SELinux on SourceForge.net, Information for various distributions

- SELinux Discussion Forum

- Fedora Project:

- "Fedora SELinux User Guide". Fedora 13 (1.5 ed.).

- "Managing Confined Services". Fedora 13 (1.4 ed.).

- Jones, M. Tim (7 May 2012) [2008]. "Anatomy of Security-Enhanced Linux". Architecture and implementation. Technical Library. IBM.

- Walsh, Daniel J (13 Nov 2013). "Visual how-to guide for SELinux policy enforcement". Opensource.com.