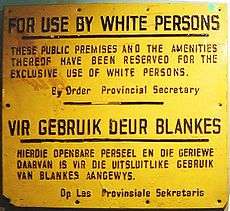

Segregation academy

| Part of a series of articles on Racial segregation | |

|---|---|

| |

| South Africa | |

| United States | |

Segregation academies were or are private schools in the United States established in the mid-20th century to enable white parents to avoid having their children in desegregated public schools, which were mandated by the U.S. Supreme Court ruling Brown v. Board of Education (1954). It had determined that segregated public schools were unconstitutional, but because Brown did not apply to private schools, the founding of new private academies in the 1950s, 1960s, and 1970s was a way for whites to practice segregation.

While these schools were established chiefly in the Southern United States, private schools existed nationwide that were heavily segregated in practice, though perhaps not intentionally.

Since the late 20th century, as social patterns in United States have changed, many of these private schools began to admit minority students; others have ceased operations. Still others, in poor, majority-black regions such as the Mississippi Delta, continue to operate with few, if any, black students.

History

The first segregation academies were created by white parents in the late 1950s in response to the U.S. Supreme Court ruling in Brown v. Board of Education (1954), which required public school boards to eliminate segregation "with all deliberate speed". Because the ruling did not apply to private schools, founding new academies provided parents a way to continue to educate their children separately from blacks. At this time, most adult blacks were still disfranchised in the South, excluded from politics and oppressed under Jim Crow.[2][3] Private academies operated outside the scope of the Brown v. Board of Education ruling and could therefore have racial segregation.[4]

Reasons why whites pulled their children out of public schools have been debated: whites insisted that "quality fueled their exodus", and blacks said "white parents refused to allow their children to be schooled alongside blacks".[5] Scholars estimate that across the nation, at least half a million white students were withdrawn from public schools between 1964 and 1975 to avoid mandatory desegregation.[2] In the 21st century, Archie Douglas, the headmaster of the Montgomery Academy (reputed to have been a segregation academy) said that he is sure "that those who resented the civil rights movement or sought to get away from it took refuge in the academy".[6] But in the 21st century, it did not practice any type of discrimination.

Seeking to revoke tax-exemption status for non-profit segregation academies, some parents in seven southern states sued the IRS in a class action that said the agency's guidelines to determine whether a private school was racially discriminatory were insufficient. (If a school discriminated racially, it was not to receive tax-exempt status.) In their suit, Allen v. Wright (1983), the plaintiffs named a number of Southern schools as representative of segregation academies.[7] The case was decided in 1984 by the U.S. Supreme Court, which ruled that citizens do not have standing to sue a federal government agency based on the influence that the agency's determinations might have on third parties (such as private schools). The judges noted the parents were in the posture of disappointed observers of the governmental process, that although the complaint asserted that "there are more than 3,500 racially segregated private academies operating in the country having a total enrollment of more than 750,000 children" (J.A. 24), it cited by name only 19 "representative" private schools, and that the parents did not allege that they or their children had applied to, been discouraged from applying to, or been denied admission to any private school or schools.[7]

Mississippi and Arkansas

In Mississippi and Arkansas, many of the segregation academies were first established in the black-majority Mississippi Delta region in northwestern Mississippi and southeastern Arkansas. The Delta has historically had a very large majority-black population, related to the history of the use of slave labor on cotton plantations. The potential for integration resulted in white parents' establishing segregation academies in every county in the Delta. Many academies are still operating, from Indianola, Mississippi to Humphreys County. These schools began to accept black students late in the 20th century, although many of them still enroll relatively small numbers of black students. In a region with low incomes among blacks, many African-American parents cannot afford the private schools. At least one school in Mississippi, Carroll Academy, receives substantial funding from the segregationist Council of Conservative Citizens.[8]

Virginia

In Virginia, segregation academies were part of a policy of massive resistance declared by U.S. Senator Harry F. Byrd, Sr. He worked to unite other white Virginia politicians and leaders in taking action to prevent school desegregation after the Brown v. Board of Education Supreme Court ruling in 1954.

In its September/October 1956 special session, the Virginia General Assembly passed a series of laws known as the Stanley plan to implement massive resistance. In January, Virginia's voters had approved an amendment to the state constitution to allow tuition grants to parents enrolling their children in private schools. Part of the Stanley plan established tuition grants program, which allowed parents who refused to allow their children to attend desegregated school funding so each could attend a private school of choice. In practice, this meant state support of newly established all-white private schools which became known as "segregation academies".

On February 18, 1958, the General Assembly passed (and Governor Almond signed) additional legislation protecting segregation, what the Byrd Organization called the "Little Rock Bill" (responding to President Eisenhower's use of federal powers to assist the court-ordered desegregation of schools in Little Rock, Arkansas).[9] Since new segregation academy facilities often failed to meet construction, health and safety standards for public schools, these were also loosened.

Segregation academies opened in various Virginia cities and counties subject to desegregation lawsuits, including Arlington, Charlottesville and Norfolk.[10] Arlington and Norfolk desegregated peacefully in February 1959. In Arlington, many (if not most) white students remained in the desegregated schools. However, that was not the case in Norfolk and other areas.

Segregation academies in Warren and Prince Edward Counties are discussed below, as examples of why even in the fall of 1963, only 3,700 black pupils or 1.6% attended school with whites. NAACP litigation had resulted in some desegregation by the fall of 1960 in eleven localities, and the number of at least partially desegregated districts had slowly risen to 20 in the fall of 1961, 29 in the fall of 1962, and 55 (out of 130 school districts) in 1963 even in 1963).[11]

Warren County also planned to integrate its only high school, Warren County High School, but Governor Almond closed the school (along with those in Charlottesville and Norfolk) in the Fall of 1958. Education continued in private and church facilities for that school year. By the Fall of 1959, John S. Mosby Academy (1-12) was constructed and opened as an all-white school. A public high school for black students was built and opened (Criser High School), and Warren County High School reopened with a significantly reduced white student population and 22 black students. Criser operated until 1966, and Mosby operated through the 1968–69 school year.

When faced with an order to integrate, Prince Edward County closed its entire school system in September 1959, and kept county schools closed until 1964, as it kept litigating (although Davis v. County School Board of Prince Edward County had been a companion case to Brown). The newly founded, private Prince Edward Academy operated as the de facto school system for white students. It enrolled K-12 students at several facilities throughout the county. Many black students were forced to move in with relatives in other counties, attend makeshift schools in church basements, or move to northern states to live with host families through a program of the Society of Friends in order to gain education. Even after public schools re-opened, Prince Edward Academy remained segregated as discussed below.

Although on January 19, 1959, the Virginia Supreme Court of Appeals struck down the new Virginia law that closed schools before integration, as contrary to a public schooling provision in the state constitution (and a three-judge federal panel struck down other provisions of the Stanley plan on the same day, the Robert E. Lee state holiday),[12] individual state tuition grants to parents continued, allowing them to patronize segregation academies.

In 1964, the Supreme Court of the United States ruled in Griffin v. County School Board of Prince Edward County that Virginia's tuition grants where the public schools had been closed for reasons of race (such as in Prince Edward County) violated the U.S. Constitution.[13] This decision finally effectively ended passive resistance within state governments, and dealt some segregation academies a fatal blow. Later rulings put the academies' tax exemption status in jeopardy if they practiced racial discrimination.

In 1978, Prince Edward Academy lost its tax exempt status. In 1986, it began accepting black students. Today it is known as the Fuqua School. All other Virginia segregation academies either closed or adopted non-racial discrimination policies. Ironically because the Catholic Church had desegregated its schools before Brown, the Huguenot Academy (a segregation academy implicitly disavowing that Catholic policy by its title), merged with Blessed Sacrament High School, a nearby Catholic High School, to become Blessed Sacrament-Huguenot. Another segregation academy, Bollingbrook, in Petersburg, Virginia merged with the Roman Catholic Gibbons High school in Petersburg and became St. Vincent De Paul High school.

See also

- The "Southern Manifesto", a document written in 1956 by legislators in the United States Congress opposed to racial integration in public places

- Runyon v. McCrary (1976): U.S. Supreme Court affirms private schools may not discriminate due to race based on 42 U.S.C. 1981.

- Allen v. Wright, a 1984 U. S. Supreme Court case challenging public subsidy for private schools that are effectively segregated.

- Educational segregation in Sunflower County, Mississippi

- en:Category:Segregation academies

References

- ↑ Moye, J. Todd. Let the People Decide: Black Freedom and White Resistance Movements in Sunflower County, Mississippi, 1945-1986. UNC Press Books, 2004. p. 243. Retrieved from Google Books on March 2, 2011. "Sunflower County's two other segregation academies— North Sunflower Academy, between Drew and Ruleville, and Central Delta Academy in Inverness— both sprouted in a similar fashion." ISBN 0-8078-5561-8, ISBN 978-0-8078-5561-4.

- 1 2 Coulson, Andrew J. (1999). Market Education: The Unknown History. Transaction Publishers. p. 275. ISBN 0-7658-0496-4.

- ↑ David Salisbury, ed. (2004). Educational Freedom in Urban America: Brown V. Board After Half a Century. CATO Institute. p. 32. ISBN 1-930865-56-2.

- ↑ Younge, Gary (2004-11-30). "Alabama clings to segregationist past". London: The Guardian. Retrieved 2006-05-02.

- ↑ Crowder, Carla (2002-10-27). "Private white academies struggle in changing world". The Birmingham News. Retrieved 2006-05-02.

- ↑ Connolly, Regan Loyola (2004-01-12). "Private schools diversify". The Montgomery Advertiser. p. 1. Archie Douglas, the headmaster of The Montgomery Academy, said that the school was started in 1959 in what he believed was a reaction to desegregation of public schools. He said, "I am sure that those who resented the civil rights movement or sought to get away from it took refuge in the academy. But, it's not 1959 anymore and The Montgomery Academy has a philosophy today that reflects the openness . . . and utter lack of discrimination with regard to race or religion that was evident in prior decades."

- 1 2 "No. 81-757, No. 81-970". Office of the solicitor general, United States department of justice. 1983. Retrieved 2006-05-02. Text of the Allen v. Wright ruling, Supreme Court of the United States.

- ↑ Carr, Sarah (December 13, 2012). "In Southern Towns, 'Segregation Academies' Are Still Going Strong". The Atlantic.

- ↑ http://www.encyclopediavirginia.org/media_player?mets_filename=evm00001088mets.xml

- ↑ Brian J. Daugherity, Keep on Keeping on (University of Virginia Press, August 2016), early draft available at http://scholarscompass.vcu.edu/cgi/viewcontent.cgi?article=1006&context=hist_pubs

- ↑ Brian Daugherity, Keep On Keeping On (University of Virginia Press, 2016) at p. 99

- ↑ "Massive Resistance". The Civil Rights Movement in Virginia. Virginia Historical Society. 2004.

- ↑ "Closing Prince Edward County's Schools". The Civil Rights Movement in Virginia. Virginia Historical Society. 2004.

External links

- "The Ground Beneath Our Feet" website

- "Massive Resistance". The Civil Rights Movement in Virginia. Virginia Historical Society. 2004.

- "Memories of busing in Richmond". Richmond History Center.

- "Brown v. Board of Education: Virginia Responds". State Library of Virginia. 2003.

- "They Closed Our Schools," the story of Massive Resistance and the closing of the Prince Edward County, Virginia public schools

- Edward H. Peeples Prince Edward County (Va.) Public Schools Collection photographs, documents, and maps exploring the history of the Prince Edward County school segregation issues of the 1950s and 1960s, from the collection of the VCU Libraries.