Baseball color line

The color line in American baseball, until the late 1940s, excluded, with some big exceptions in the 19th century until the line was firmly drawn, players of Black African descent from Major League Baseball and its affiliated Minor Leagues. Racial segregation in professional baseball was sometimes called a gentlemen's agreement, meaning a tacit understanding, as there was no written policy at the highest level of organized baseball, the major leagues. But a high minor league's vote in 1887 against allowing new contracts with black players within its league sent a powerful signal that eventually led to the disappearance of blacks from the sport's other minor leagues later that century, including the low minors.

After the line was in virtually full effect in the early 20th century, many black baseball clubs were established, especially during the 1920s to 1940s when there were several Negro Leagues. During this period some light-skinned Hispanic players, Native Americans, and native Hawaiians were able to play in the Major Leagues.

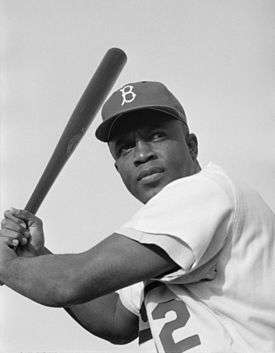

The color line was broken for good when Jackie Robinson signed with the Brooklyn Dodgers organization for the 1946 season. In 1947, both Robinson in the National League and Larry Doby with the American League's Cleveland Indians appeared in games for their teams. By the late 1950s, the percentage of black players on Major League teams matched or exceeded that of the general population.

Origins

.jpg)

Formal beginning of segregation followed the baseball season of 1867. On October 16, the Pennsylvania State Convention of Baseball in Harrisburg denied admission to the "colored" Pythian Baseball Club.[1]

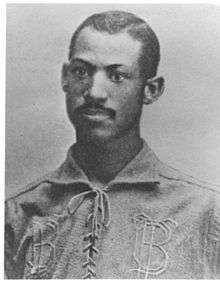

Major League Baseball's National League, founded in 1876, had no black players in the 19th century, except for a recently discovered one, William Edward White, who played in a single game in 1879 and who apparently passed for being white. The National League and the other main major league of the day, the American Association, had no written rules against having African American players. In 1884, the American Association had two black players, Moses Fleetwood Walker and, for a few months of the season, his brother Weldy Walker, both of whom played for the Toledo Blue Stockings.

The year before, in 1883, prominent National League player Cap Anson had threatened to have his Chicago team sit out an exhibition game at then-minor league Toledo if Toledo's Fleet Walker played. Anson backed down, but not before uttering the “N word” on the field and vowing that his team would not play in such a game again.[2]

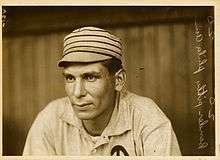

In 1884, the Chicago club made a successful threat months in advance of another exhibition game at Toledo, to have Fleet Walker sit out. In 1887, Anson made a successful threat by telegram before an exhibition game against the Newark Little Giants of the International League that it must not play its two black players, Fleet Walker and pitcher George Stovey.[3]

An unsettled question is how far to spread the blame, to players such as Anson and racism in society at large as of the mid-1880s, for the most noted vote in 19th-century professional baseball in favor of segregation: a July 14, 1887 one by the high-minor International League to ban the signing of new contracts with black players. By a 6-to-4 vote, the league’s entirely white teams voted in favor and those with at least one black player voted in the negative. The Binghamton, N.Y., team, which had just released its two black players, voted with the majority.[4]

Right after the vote, the sports weekly Sporting Life stated, “Several representatives declared that many of the best players in the league are anxious to leave on account of the colored element, and the board finally directed Secretary [C.D.] White to approve of no more contracts with colored men.” A lengthy 2016 essay that focused on claims of Anson’s alleged influence on the vote cited the Sporting Life report and showed that several historians have been lax by not conveying that Anson’s influence on the vote is a matter of speculation.[5]

On the afternoon of the International League vote, Anson’s Chicago team played the above-alluded-to game at Newark, with Stovey and the apparently injured Walker sitting out. Some historians who have come down hard on Anson rewrote the sequence of events that day to undo the fact that the league vote took place at a meeting that was convened in the morning, before the game that afternoon. The essay’s writer, Anson book-length biographer Howard W. Rosenberg, concluded that, “A fairer argument is that rather than being an architect [of segregation in professional baseball, as the late baseball racism historian Jules Tygiel termed Anson in his 1983 Baseball’s Great Experiment: Jackie Robinson and His Legacy], that he was a reinforcer of it, including in the National League – and that he had no demonstrable influence on changing the course of events apart from his team’s exhibition-game schedule.” The year 1887 was also the high point of achievement of blacks in the high minor leagues, and each National League team that year except for Chicago played exhibition games against teams with black players, including against Newark and other International League teams.[6]

Some of Anson’s notoriety stems from a 1907 book on early blacks in baseball by black minor league player and later black semi-professional team manager Sol White, who was elected to the Hall of Fame in 2006. White’s claims against Anson, such as that, “Were it not for this same man Anson, there would have been a colored player in the National League in 1887,” were analyzed at length by Rosenberg in his 2006 Anson biography and are referenced in a few places in his 2016 essay.[7]

After the 1887 season, the International League retained just two blacks for the 1888 season, both of whom were under contracts signed before the 1887 vote, Frank Grant of the Buffalo Bisons and Moses Fleetwood Walker of the Syracuse franchise, with Walker staying in the league for most of 1889.

In September 1887, eight members of the St. Louis Browns of the then-major American Association (who would ultimately change their nickname to the current St. Louis Cardinals) staged a mutiny during a road trip, refusing to play a game against the New York Cuban Giants, the first all-black professional baseball club, and citing both racial and practical reasons: that the players were banged up and wanted to rest so as to not lose their hold on first place. At the time, the St. Louis team was in Philadelphia, and a story that ran in the Philadelphia Times stated that “for the first time in the history of base ball the color line has been drawn." [8]

Blacks were gone from the high minors after 1889 and a trickle of them were left in the minor leagues within a decade. Besides White’s single game in 1879, the lone blacks in major league baseball for around 75 years were Fleet Walker and his brother Weldy, both in 1884 with Toledo.

A big change would take place starting in 1946, when Jackie Robinson played for the Montreal Royals in, fittingly, the International League.[9]

Covert efforts at integration

While professional baseball was regarded as a strictly white-men-only affair, in fact the racial color bar was directed against black players exclusively. Other races were allowed to play in professional white baseball. One example was Charles Albert Bender, a star pitcher for the Philadelphia Athletics in 1910. Bender was the son of a Chippewa Indian mother and a German father and had the inevitable nickname "Chief" from the white players.[10]

As a result of this exclusive treatment of black players, deceptive tactics were used by managers to sign African Americans, including several attempts, with the player's acquiescence, to sign players who they knew full well were African American as Native Americans despite the ban. In 1901, John McGraw, manager of the Baltimore Orioles, tried to add Charlie Grant to the roster as his second baseman. He tried to get around the Gentleman's Agreement by trying to pass him as a Cherokee Indian named Charlie Tokohama. Grant went along with the charade. However, in Chicago Grant's African American friends who came to see him try out gave him away and Grant never got an opportunity to play ball in the big leagues.[11]

On May 28, 1916, British Columbian Jimmy Claxton temporarily broke the professional baseball color barrier when he played two games for the Oakland Oaks of the Pacific Coast League. Claxton was introduced to the team owner by a part-Native-American friend as a fellow member of an Oklahoma tribe. The Zee-Nut candy company rushed out a baseball card for Claxton.[10] However, within a week, a friend of Claxton revealed that he had both Negro and Native American ancestors, and Claxton was promptly fired.[12] It would be nearly thirty more years before another black man, at least one known to be black, played organized white baseball.

There possibly were attempts to have people of African descent be signed as Hispanics. One possible attempt may have occurred in 1911 when the Cincinnati Reds signed two light-skinned players from Cuba, Armando Marsans and Rafael Almeida. Both of them had played "Negro Baseball", barnstorming as members of the integrated All Cubans. When questions arose about them playing the white man's game, the Cincinnati managers assured the public that "...they were as pure white as Castile soap."[10]

The African American newspaper New York Age had this to say about the signings:

Now that the first shock is over, it will not be surprising to see a Cuban a few shades darker breaking into the professional ranks. It would then be easier for colored players who are citizens of this country to get into fast company.[10]

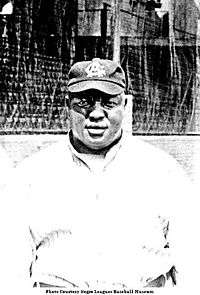

The Negro leagues

The Negro National League was founded in 1920 by Rube Foster, independent of Organized Baseball's National Commission (1903–1920). The NNL survived through 1931, primarily in the midwest, accompanied by the major Eastern Colored League for several seasons to 1928. "National" and "American" Negro leagues were established in 1933 and 1937 which persisted until integration. The Negro Southern League operated consecutively from 1920, usually at a lower level. None of them, nor any integrated teams, were members of Organized Baseball, the system led by Commissioner Landis from 1921. Rather, until 1946 professional baseball in the United States was played in two racially segregated league systems, one on each side of the so-called color line. Much of that time there were two high-level "Negro major leagues" with a championship playoff or all-star game, as between the white major leagues.

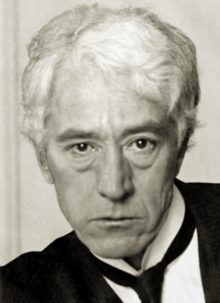

Kenesaw Mountain Landis

During his 1921–1944 tenure as the first baseball commissioner, Kenesaw Mountain Landis has been alleged to have been particularly determined to maintain the segregation. It is possible that he was guided by his background as a federal judge, and specifically by the then-existing constitutional doctrine of "separate but equal" institutions (see Plessy v. Ferguson). He himself maintained for many years that black players could not be integrated into the major leagues without heavily compensating the owners of Negro league teams for what would likely result in the loss of their investments. In addition, integration at the major league level would likely have necessitated integrating the minor leagues, which were much more heavily distributed through the rural U.S. South and Midwest.

Although Landis had served an important role in helping to restore the integrity of the game after the 1919 World Series scandal, his unyielding stance on the subject of baseball's color line was an impediment. His death in late 1944 was opportune, as it resulted in the appointment of a new Commissioner, Happy Chandler, who was much more open to integration than Landis was.

From the purely operational viewpoint, Landis' predictions on the matter would prove to be correct. The eventual integration of baseball spelled the demise of the Negro leagues, and integration of the southern minor leagues was a difficult challenge.

Bill Veeck and Branch Rickey

The only serious attempt to break the color line during Landis' tenure came in 1942, when Bill Veeck tried to buy the then-moribund Philadelphia Phillies and stock them with Negro league stars. However, when Landis got wind of his plans,[13] he and National League president Ford Frick scuttled it in favor of another bid by William D. Cox.

In his autobiography, Veeck, as in Wreck, in which he discussed his abortive attempt to buy the Phillies, Veeck also stated that he wanted to hire black players for the simple reason that in his opinion the best black athletes "can run faster and jump higher" than the best white athletes.[14] Veeck realized that there was no actual rule against integration; it was just an unwritten policy, a "Gentlemen's Agreement." Veeck stated that Landis and Frick prevented him from buying and thus integrating the Phillies, on various grounds.

The authors of a controversial article in the 1998 issue of SABR's The National Pastime argued that Veeck invented the story of buying the Phillies, claiming Philadelphia's black press made no mention of a prospective sale to Veeck.[15] Subsequently, the article was strongly challenged by the late historian Jules Tygiel, who refuted it point-by-point in an article in the 2006 issue of SABR's The Baseball Research Journal,[16] and in an appendix, entitled "Did Bill Veeck Lie About His Plan to Purchase the ’43 Phillies?", published in Paul Dickson's biography, Bill Veeck: Baseball's Greatest Maverick.[17] Joseph Thomas Moore wrote in his biography of Doby, "Bill Veeck planned to buy the Philadelphia Phillies with the as yet unannounced intention of breaking that color line."[18] Ironically, the Phillies ended up being the last National League team, and third-last team in the majors, to integrate, with John Kennedy debuting for the Phillies in 1957, 15 years after Veeck's attempted purchase.

Around 1945, Branch Rickey, General Manager of the Brooklyn Dodgers, held tryouts of black players, under the cover story of forming a new team called the "Brooklyn Brown Dodgers." The Dodgers were, in fact, looking for the right man to break the color line. Rickey had an advantage in that he was already an employee of the Dodgers. Also, Landis had died by this time and new commissioner Happy Chandler was more supportive of integrating the major leagues.

Jackie Robinson and Larry Doby

The color line was breached when Rickey, with Chandler's support, signed the African American player Jackie Robinson in October 1945, intending him to play for the Dodgers. Chandler later wrote in his biography that although he risked losing his job as commissioner, he could not in good conscience tell black players they could not play with white players when they had fought alongside them in World War II.

After a year in the minor leagues with the Dodgers' top minor-league affiliate, the Montreal Royals of the International League, Robinson was called up to the Dodgers in 1947. He endured epithets and death threats and got off to a slow start. However, his athleticism and skill earned him the first ever Rookie of the Year award, which is now named in his honor.

Less well-known was Larry Doby, who signed with Bill Veeck's Cleveland Indians that same year to become the American League's first African American player. Doby, a more low-key figure than Robinson, suffered many of the same indignities that Robinson did, albeit with less press coverage. As baseball historian Daniel Okrent wrote, "Robinson had a two year drum roll, Doby just showed up."[19] Both men were ultimately elected to the Baseball Hall of Fame on the merits of their play. Due to their success, teams gradually integrated African Americans on their rosters. (Almost a dozen years after his 1947 debut, Doby would become the first American player of African descent to appear for the Detroit Tigers, on April 10, 1959.)

Prior to the integration of the major leagues, the Brooklyn Dodgers led the integration of the minor leagues. Jackie Robinson and Johnny Wright were assigned to Montreal, but also that season Don Newcombe and Roy Campanella became members of the Nashua Dodgers in the class-B New England League. Nashua was the first minor-league team based in the United States to integrate its roster after 1898. Subsequently that season, the Pawtucket Slaters, the Boston Braves' New England League franchise, also integrated its roster, as did Brooklyn's class-C franchise in Trois-Rivières, Quebec. With one exception, the rest of the minor leagues would slowly integrate as well, including those based in the southern United States. The Carolina League, for example, integrated in 1951 when the Danville Leafs signed Percy Miller Jr. to their team.

The exception was the Class AA Southern Association. Founded in 1901 and based in the Deep South, it allowed only one black player, Nat Peeples of the 1954 Atlanta Crackers, a brief appearance in the league. Peeples went hitless in two games played and four at bats on April 9–10, 1954, was demoted one classification to the Jacksonville Braves of the Sally League, and the SA reverted to white-only status. As a result, its major-league parent clubs were forced to field all-white teams during the 1950s. By the end of the 1950s, the SA also was boycotted by civil rights leaders. The Association finally ceased operation after the 1961 season, still a bastion of segregation. Its member teams joined the International, Sally and Texas leagues, which were all racially integrated.

Reluctance of Boston Red Sox

The Boston Red Sox were the last major league team to integrate, holding out until 1959.[20] This was allegedly due to the steadfast resistance provided by team owner Tom Yawkey. In April 1945, the Red Sox refused to consider signing Jackie Robinson (and future Boston Braves outfielder Sam Jethroe) after giving him a brief tryout at Fenway Park.[20] The tryout, however, was a farce chiefly designed to assuage the desegregationist sensibilities of powerful Boston City Councilman Isadore Muchnick.[21] Even with the stands limited to management, Robinson was subjected to racial epithets.[20] Robinson left the tryout humiliated.[22] Robinson would later call Yawkey "one of the most bigoted guys in baseball".[23]

Boston city councilor Isadore Muchnick further spurred the Robinson tryout by threatening to revoke the team's exemption from Sunday blue laws. The segregation policy was enforced by Yawkey's general managers: Eddie Collins (through 1947), and Joe Cronin (1948–58). A pennant winning team in 1946, the year before integration, the Red Sox would perpetually fail to make the playoffs for the next twenty seasons, with implications being that Boston shut itself out by ignoring the expanded talent pool of black players.

On April 7, 1959 during spring training, Yawkey and general manager Bucky Harris were named in a lawsuit charging them with discrimination and the deliberate barring of black players from the Red Sox.[24] The NAACP issued charges of "following an anti-Negro policy", and the Massachusetts Commission Against Discrimination announced a public hearing on racial bias against the Red Sox.[25] Thus, the Red Sox were forced to integrate, becoming the last pre-expansion major-league team to do so when Harris promoted Pumpsie Green from Boston's AAA farm club. On July 21, Green debuted for the team as a pinch runner, and would be joined later that season by Earl Wilson, the second black player to play for the Red Sox.[26] In the early to mid 1960s, the team added other players of color to their roster including Joe Foy, José Tartabull, George Scott, George Smith, John Wyatt, Elston Howard and Reggie Smith. The 1967 Red Sox went on to win the "Impossible Dream" pennant but lost to the St. Louis Cardinals in seven games in that year's World Series.

Tom Yawkey died in 1976, and his widow Jean Yawkey eventually sold the team to Haywood Sullivan and Edward "Buddy" LeRoux. As chief executive, Haywood Sullivan found himself in another racial wrangle that ended in a courtroom. The Elks Club of Winter Haven, Florida, the Red Sox spring training home, did not permit black members or guests. Yet the Red Sox allowed the Elks into their clubhouse to distribute dinner invitations to the team's white players, coaches, and business management. When the African-American Tommy Harper, a popular former player and coach for Boston, then working as a minor league instructor, protested the policy and a story appeared in the Boston Globe, he was promptly fired. Harper sued the Red Sox for racial discrimination and his complaint was upheld on July 1, 1986.[27]

Statistics

| Year | Major leagues | Population | Ratio |

| 1959 | 17% | 11% | 3:2 |

| 1975 | 27% | 11% | 5:2 |

| 2010 | 8% | 12% | 2:3 |

The under-representation of black players in U.S. baseball ended during the early years of the Civil rights movement, but has fallen in recent years and as of 2010 was lower than in 1959 when the hiring of black players was still very controversial.

Professional baseball firsts

- player, professional: Bud Fowler, 1878. Fowler never played in the major leagues.

- player, major leagues: Moses Fleetwood Walker, debut game May 1, 1884, catcher for Toledo at Louisville

- all-black team, openly professional: Cuban Giants, 1885

- first professional league in the U.S. to be integrated: California Winter League, 1910

- all-black team in a minor league:

- pitcher, major leagues: Dan Bankhead, debut game August 26, 1947, for Brooklyn at home[30]

- All-Star selection: Roy Campanella, Larry Doby, Don Newcombe, Jackie Robinson, 1949[31]

- Most Valuable Player, major leagues: Jackie Robinson, 1949

- field manager, level AAA: Héctor López, 1969

- nine-man lineup, major leagues: Pittsburgh Pirates, 1971

- first black coach, major leagues: Buck O'Neil, Chicago Cubs, 1962

- field manager, major leagues: Frank Robinson, debut game April 8, 1975, for Cleveland at home *

- general manager, major leagues: Bill Lucas, 1976

- First World Series winning field manager: Cito Gaston 1992 with the Toronto Blue Jays. He repeated the next season.

- First World Series Walk-Off Homerun: Joe Carter 1993 with the Toronto Blue Jays.

- First National League field manager to manage a World Series: Dusty Baker 2002 with the San Francisco Giants.

* A case has been made for Ernie Banks as the de facto first black manager in the major leagues. On May 8, 1973, Chicago Cubs manager Whitey Lockman was ejected from the game. Coach Ernie Banks filled in as manager for two innings of the 12-inning 3–2 win over the San Diego Padres. The Sporting News Official Baseball Guide prior to the 1974 season stated flatly that on May 8, "Ernie Banks became the major leagues' first black manager, but only for a day" (page 129). The other two regular coaches on the team were absent that day, opening this door for Banks for the one occasion, but Banks never became a manager on a permanent basis.

See also

- History of baseball in the United States

- Negro league baseball

- List of first black Major League Baseball players by team and date

- Race and ethnicity in the NBA

- List of African-American firsts

Further reading

- Gordon, Patrick. Octavius Catto & the Pythian Baseball Club: The beginnings of black baseball. Philadelphia Baseball Review. March 2008.

- Gordon, Patrick. On the field, the Pythian Club was rivaled by few: Catto led a stellar organization. Philadelphia Baseball Review. April 2008.

- Heaphy, Leslie A. The Negro Leagues 1869–1960. Jefferson, North Carolina: McFarland. 2003.

- Lamb, Chris. Conspiracy of Silence: Sportswriters and the Long Campaign to Desegregate Baseball. Lincoln, Nebraska: University of Nebraska Press, 2012.

- Lanctot, Neil. Negro League Baseball: The Rise and Ruin of a Black Institution. Philadelphia: U. of Penn. Press. 2004.

- McNeil, William F. Black Baseball Out of Season: pay for play outside of the Negro Leagues. Jefferson, North Carolina: McFarland. 2007.

- Olsen, Jack. The Black Athlete: A Shameful Story; The Myth of Integration in American Sport. Time-Life Books. 1968.

- Rhoden, William C. $40 Million Slaves: The Rise, Fall, and Redemption of the Black Athlete. Crown Publishers. 2006.

References

- Notes

- ↑ Gordon, Patrick (April 2008). "On the field, Pythian baseball club was rivaled by few". Philadelphia Baseball Review. Archived from the original on 2011-05-13. Retrieved 2013-08-30.

The Pythians finished 1867 with a 9–1 record but suffered a setback on October 16 in Harrisburg when the club applied and was denied admission into the Pennsylvania State Convention of Baseball, a state organization designed to promote a professional approach to the game. "The committee reported favorably on all credentials except for the ones presented by the Pythians, which theyintentionally neglected", noted author Michael Lomax. The National Association of Amateur Baseball Players upheld the Pennsylvania State Association's ruling and adopted a formal ban on the inclusion of black players and clubs.

- ↑ Husman, John R. "August 10, 1883: Cap Anson vs. Fleet Walker". the Society for American Baseball Research.

- ↑ Mancuso, Peter. "July 14, 1887: The color line is drawn"., the Society for American Baseball Research.

- ↑ Rosenberg, Howard W. "Fantasy Baseball: The Momentous Drawing of the Sport's 19th-Century 'Color Line' is still Tripping up History Writers,". The Atavist, June 14, 2016.

- ↑ Rosenberg. "Fantasy Baseball,". ibid.

- ↑ Rosenberg. "Fantasy Baseball,". ibid., in part citing, for exhibition game data, Bond, Gregory. "Jim Crow at Play: Race, Manliness, and the Color Line in American Sports, 1876–1916"., dissertation, Doctor of Philosophy (History), p. 262.

- ↑ Rosenberg, Howard W. (2006). Cap Anson 4: Bigger Than Babe Ruth: Captain Anson of Chicago. Tile Books. ISBN 978-0-9725574-3-6., pp. 423, 425–30 and Rosenberg. "Fantasy Baseball,". ibid. Additional notoriety of Anson has been generated by authors who state, as a matter of fact, that because he was a huge star, that he had influence on matters of race extending to the International League vote. In his essay, Rosenberg added to his book’s argumentation that it is not at all obvious that he had “coattails” in that respect by claiming that “his personality, which was contrarian and ‘bluff and gruff,’ arguably made him someone unlikely for others – other than his own teammates – to have been persuaded or compelled to follow on controversial matters involving, on some level, personal taste.”

- ↑ Rosenberg. Cap Anson 4., p. 433 and Rowell, Jeffrey Clarke. "Moses Fleetwood Walker and the Establishment of a Color Line in Major League Baseball, 1884–1887" (PDF)., Atlanta Review of Journalism History, p. 111.

- ↑ "Breaking a Barrier 60 Years Before Robinson," The New York Times, July 27, 2006.

- 1 2 3 4 "The Faith of Fifty Million People: Top of the 3rd Inning (First half of the third episode)". Ken Burns's Baseball. September 20, 1994.

- ↑ Ken Burns's Baseball' "Something Like a War" Top of the second inning (first half of episode two) Original airdate: Monday, September 19, 1994

- ↑ "Sporting News". Retrieved 2009-06-28.

- ↑ Moore, Joseph Thomas (1988). Pride and Prejudice: The Biography of Larry Doby. New York: Praeger Publishers. p. 40. ISBN 0275929841.

- ↑ Veeck — as in Wreck, p. 171, by Bill Veeck with Ed Linn, G. P. Putnam's Sons, 1962.

- ↑ Jordan, David M; Gerlach, Larry R; Rossi, John P. "A Baseball Myth Exploded" (PDF)

- ↑ Revisiting Bill Veeck and the 1943 Phillies, The National Pastime, 2006, p. 109. Retrieved 2012-05-12.

- ↑ Dickson, Paul (2012). Bill Veeck: Baseball's Greatest Maverick. New York: Walker & Company. ISBN 978-0-8027-1778-8.

- ↑ Moore, Joseph Thomas (1988). Pride Against Prejudice: The Biography of Larry Doby. New York: Praeger Publishers. p. 19. ISBN 0275929841.

- ↑ Moore, Joseph Thomas; Dickson, Paul (1988). Larry Doby: The Struggle of the American League's First Black Player. New York: Greenwood Press. p. x. ISBN 9780486483375.

- 1 2 3 NPR (2002). "The Boston Red Sox and Racism with New Owners, Team Confronts Legacy of Intolerance". NPR. Archived from the original on 9 July 2008. Retrieved 2008-06-27

- ↑ Simon, pp. 46–47.

- ↑ Bryant, p. 31.

- ↑ "Ted Williams: A life remembered". Boston.com. Retrieved 2013-08-31.

- ↑ New York Times April 7, 1959

- ↑ Bleacher Report April 16, 2009 by Harold Friend

- ↑ "The Red Sox Encyclopedia". Google Books. Retrieved 2013-08-31.

- ↑ Bryant, Howard, Shut Out: A Story of Race and Baseball in Boston. Boston: Beacon Press, 2002.

- ↑ Nightengale, Bob (April 15, 2012). "Number of African-American baseball players dips again". USA Today. Retrieved 2013-08-31.

- ↑ "Information Please Almanac". Infoplease.com. Retrieved 2013-08-31.

- ↑ "Famous Baseball Firsts in the Postwar Era". Baseball-almanac.com. Retrieved 2013-08-31.

- ↑ "1949 All-Star Game". Baseball-Almanac.com. Retrieved 18 August 2012.

External links

- Historical Society of Pennsylvania. Playing for Keeps: Philadelphia's Pythian Base Ball Club.