Shofetim (parsha)

Shofetim or Shoftim (שֹׁפְטִים — Hebrew for "judges," the first word in the parashah) is the 48th weekly Torah portion (פָּרָשָׁה, parashah) in the annual Jewish cycle of Torah reading and the fifth in the Book of Deuteronomy. It constitutes Deuteronomy 16:18–21:9. This parashah has 5590 letters, 1523 words, and 97 verses and can occupy about 192 lines in a sefer Torah.[1]

Jews generally read it in August or September.[2]

The parashah provides a constitution — a basic societal structure — for the Israelites. The parashah sets out rules for judges, kings, Levites, prophets, cities of refuge, witnesses, war, and unsolved murder victims.

Readings

In traditional Sabbath Torah reading, the parashah is divided into seven aliyot or "readings" (עליות). In the Masoretic Text, Parashah Shofetim has four "open portion" (פתוחה, petuchah) divisions (roughly equivalent to paragraphs, often abbreviated with the Hebrew letter פ pe). Parashah Shofetim has several further subdivisions, called "closed portions" (סתומה, setumah, abbreviated with the Hebrew letter ס samekh) within the open portion divisions. The short first open portion divides the first reading. The long second open portion goes from the middle of the first reading to the middle of the fifth reading. The third open portion goes from the middle of the fifth reading to the middle of the seventh. The final, fourth open portion divides the seventh reading. Closed portion divisions further divide the first, fifth, and sixth aliyot, and each of the short second and third aliyot constitutes a closed portion of its own.[3]

First reading — Deuteronomy 16:18–17:13

In the first reading, Moses directed the Israelites to appoint judges (shophet) and officials for their tribes to govern the people with justice, with impartiality, and without bribes.[4] "Justice, justice shalt thou follow", he said.[5] A closed portion ends here.[6]

In the continuation of the reading, Moses warned the Israelites against setting up a sacred post beside God's altar or erecting a baetylus.[7] A closed portion ends here with the end of chapter 16.[6]

In the continuation of the reading, Moses warned the Israelites against the korban (sacrifice) of an ox or sheep with any serious congenital disorder.[8] Another closed portion ends here.[6]

And as the reading continues, Moses instructed that if the Israelites found a person who worshiped other gods — the sun, the moon, or other astronomical object — then they were to make a thorough inquiry, and if they established the fact on the testimony of two or more witnesses, then they were to stone the person to death, with the witnesses throwing the first stones.[9] The first open portion ends here.[10]

In the continuation of the reading, Moses taught that if a legal case proved too baffling for the Israelites to decide, then they were promptly to go to Temple in Jerusalem, appear before the kohenim or judge in charge, and present their problem, and carry out any verdict that was announced there without deviating either to the right or to the left.[11] They were to execute any man who presumptuously disregarded the priest or the judge, so that all the people would hear, be afraid, and not act presumptuously again.[12] The first reading and a closed portion end here.[13]

Second reading — Deuteronomy 17:14–20

In the second reading, Moses instructed that if, after the Israelites had settled the Land of Israel, they decided to set a king over them, they were to be free to do so, taking an Israelite chosen by God.[14] The king was not to keep many horses, marry many wives, or amass excess silver and gold.[15] The king was to write for himself a copy of this Teaching to remain with him and read all his life, so that he might learn to revere God and faithfully observe these laws.[16] He would thus not act haughtily toward his people nor deviate from the law, and as a consequence, he and his descendants would enjoy a long reign.[17] The second reading and a closed portion end here with the end of chapter 17.[18]

Third reading — Deuteronomy 18:1–5

In the third reading, Moses explained that the Levites were to have no territorial portion, but were to live only on offerings, for God was to be their portion.[19] In exchange for their service to God, the priests were to receive the shoulder, cheeks, and stomach of sacrifices, the first fruits of the Israelites' cereal, wine, oil, and the first sheep shearing.[20] The third reading and a closed portion end here.[21]

Fourth reading — Deuteronomy 18:6–13

In the fourth reading, Moses told that the country-based Levites were to be free to come from their settlements to the place that God chose as a shrine to serve with their fellow Levites based there, and there they were to receive equal shares of the dues.[22] A closed portion ends here.[21]

In the continuation of the reading, Moses instructed that the Israelites were not to imitate the abhorrent practices of the nations that they were displacing, consign their children to fire, or act as an augur, soothsayer, diviner, sorcerer, one who casts spells, one who consults ghosts or familiar spirits, or one who inquires of the dead, for it was because of those abhorrent acts that God was dispossessing the residents of the land.[23] The fourth reading ends here.[24]

Fifth reading — Deuteronomy 18:14–19:13

In the fifth reading, Moses foretold that God would raise a prophet from among them like Moses and the Israelites were to heed him.[25] When at Mount Horeb, the Israelites had asked not to hear God's voice directly;[26] God created the role of the prophet to speak God's words, promising to hold to account anybody who failed to heed the prophet's words.[27] But any prophet who presumed to speak an oracle in God's name that God had not commanded, or who spoke in the name of other gods, was to die.[28] This was how the people were to determine whether God spoke the oracle: If the prophet spoke in the name of God and the oracle did not come true, then God had not spoken that oracle, the prophet had uttered it presumptuously, and the people were not to fear him.[29] A closed portion ends here with the end of chapter 18.[30]

In the continuation of the reading, Moses instructed that when the Israelites had settled in the land, they were to divide the land into three parts and set aside three Cities of Refuge, so that any manslayer could have a place to which to flee.[31] And if the Israelites faithfully observed all the law and God enlarged the territory, then they were to add three more towns to those three.[32] Only a manslayer who had killed another unwittingly, without being the other's enemy, might flee there and live.[33] For instance, if a man went with his neighbor into a grove to cut wood, and as he swung an axe, the axe-head flew off the handle and struck and killed the neighbor, then the man could flee to one of the cities of refuge and live.[34] The second open portion ends here.[35]

In the continuation of the reading, Moses instructed that if, however, one who was the enemy of another lay in wait, struck the other a fatal blow, and then fled to a city of refuge, the elders of the slayer's town were to have the slayer turned over to the blood-avenger to be put to death.[36] The fifth reading and a closed portion end here.[37]

Sixth reading — Deuteronomy 19:14–20:9

In the sixth reading, Moses warned that the Israelites were not to move their countrymen's landmarks, set up by previous generations, in the property that they were allotted in the land.[38] A closed portion ends here.[37]

In the continuation of the reading, Moses instructed that an Israelite could be found guilty of an offense only on the testimony of two or more witnesses.[39] If one person gave false testimony against another, then the two parties were to appear before God and the priests or judges, the judges were to make a thorough investigation, and if they found the person to have testified falsely, then they were to do to the witness as the witness schemed to do to the other.[40] A closed portion ends here with the end of chapter 19.[41]

In the continuation of the reading, Moses taught that before the Israelites joined battle, the priest was to tell the troops not to fear, for God would accompany them.[42] Then the officials were to ask the troops whether anyone had built a new house but not dedicated it, planted a vineyard but never harvested it, paid the bride-price for a wife but not yet married her, or become afraid and disheartened, and all these they were to send back to their homes.[43] The sixth reading and a closed portion end with Deuteronomy 20:9.[44]

Seventh reading — Deuteronomy 20:10–21:9

In the seventh reading, Moses instructed that when the Israelites approached to attack a town, they were to offer it terms of peace, and if the town surrendered, then all the people of the town were to serve the Israelites as slaves.[45] But if the town did not surrender, then the Israelites were to lay siege to the town, and when God granted victory, kill all its men and take as booty the women, children, livestock, and everything else in the town.[46] Those were the rules for towns that lay very far from Israel, but for the towns of the nations in the land — the Hittites, Amorites, Canaanites, Perizzites, Hivites, and Jebusites — the Israelites were to kill everyone, lest they lead the Israelites into doing all the abhorrent things that those nations had done for their gods.[47] A closed portion ends here.[48]

In the continuation of the reading, Moses instructed that when the Israelites besieged a city for a long time, they could eat the fruit of the city's trees, but they were not to cut down any trees that could yield food.[49] The third open portion ends here with the end of chapter 20.[50]

In the continuation of the reading, Moses taught that if, in the land, they found the body of a murder victim lying in the open, and they could not determine the killer, then the elders and judges were to measure the distances from the corpse to the nearby towns.[51] The elders of the nearest town were to take a heifer that had never worked down to an ever-flowing wadi and break its neck.[52] The priests were to come forward, and all the elders were to wash their hands over the heifer.[53]

In the maftir (מפטיר) reading of Deuteronomy 21:7–9 that concludes the parashah,[54] the elders were to declare that their hands did not shed the blood nor their eyes see it, and they were to ask God to absolve the Israelites, and not let guilt for the blood of the innocent remain among them, and God would absolve them of bloodguilt.[55] Deuteronomy 21:9 concludes the final closed portion.[56]

Readings according to the triennial cycle

Jews who read the Torah according to the triennial cycle of Torah reading read the parashah according to the following schedule:[57]

| Year 1 | Year 2 | Year 3 | |

|---|---|---|---|

| 2013–2014, 2016–2017, 2019–2020 ... | 2014–2015, 2017–2018, 2020–2021 ... | 2015–2016, 2018–2019, 2021–2022 ... | |

| Reading | 16:18–18:5 | 18:6–19:13 | 19:14–21:9 |

| 1 | 16:18–20 | 18:6–8 | 19:14–21 |

| 2 | 16:21–17:7 | 18:9–13 | 20:1–4 |

| 3 | 17:8–10 | 18:14–17 | 20:5–9 |

| 4 | 17:11–13 | 18:18–22 | 20:10–14 |

| 5 | 17:14–17 | 19:1–7 | 20:15–20 |

| 6 | 17:18–20 | 19:8–10 | 21:1–6 |

| 7 | 18:1–5 | 19:11–13 | 21:7–9 |

| Maftir | 18:3–5 | 19:11–13 | 21:7–9 |

In ancient parallels

The parashah has parallels in these ancient sources:

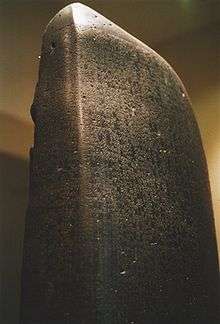

Deuteronomy chapter 19

The Code of Hammurabi contained precursors of the law of "an eye for an eye" in Deuteronomy 19:16–21. The Code of Hammurabi provided that if a man destroyed the eye of another man, they were to destroy his eye. If one broke a man's bone, they were to break his bone. If one destroyed the eye of a commoner or broke the bone of a commoner, he was to pay one mina of silver. If one destroyed the eye of a slave or broke a bone of a slave, he was to pay one-half the slave's price. If a man knocked out a tooth of a man of his own rank, they were to knock out his tooth. If one knocked out a tooth of a commoner, he was to pay one-third of a mina of silver. If a man struck a man's daughter and brought about a miscarriage, he was to pay 10 shekels of silver for her miscarriage. If the woman died, they were to put the man's daughter to death. If a man struck the daughter of a commoner and brought about a miscarriage, he was to pay five shekels of silver. If the woman died, he was to pay one-half of a mina of silver. If he struck a man's female slave and brought about a miscarriage, he was to pay two shekels of silver. If the female slave died, he was to pay one-third of a mina of silver.[58]

In inner-biblical interpretation

The parashah has parallels or is discussed in these Biblical sources:[59]

Deuteronomy chapters 12–26

Professor Benjamin Sommer of the Jewish Theological Seminary of America argued that Deuteronomy 12–26 borrowed whole sections from the earlier text of Exodus 21–23.[60]

Deuteronomy chapter 16

Deuteronomy 16:18 instructs the Israelites to appoint judges and officers in all their cities. Similarly, 2 Chronicles 19:5–11 reports that Jehoshaphat appointed judges throughout all the fortified cities of Judah.

Deuteronomy 16:19 requires fairness in the administration of justice. Earlier, in Exodus 23:2, God told Moses to tell the people not to follow a multitude to do wrong, nor to bear witness in a dispute to turn aside after a multitude to pervert justice. And in Exodus 23:6, God instructed the people not to subvert the rights of the poor in their disputes. Along the same lines, in Deuteronomy 24:17, Moses admonished against perverting the justice due to the stranger or the orphan, and in Deuteronomy 27:19, Moses invoked a curse on those who pervert the justice due to the stranger, orphan, and widow. Among the prophets, in Isaiah 10:1–2, the prophet invoked woe on those who decree unrighteous decrees to the detriment of the needy, the poor, widows, or orphans and in Amos 5:12, the prophet berated the sins of afflicting the just and turning aside the needy in judicial proceedings. In the writings, Proverbs 17:23 warns that a wicked person takes a gift to pervert the ways of justice. Deuteronomy 16:19 states the rule most broadly, when Moses said simply, "You shall not judge unfairly."

Similarly, Deuteronomy 16:19 prohibits showing partiality in judicial proceedings. Earlier, in Exodus 23:3, God told Moses to tell the people, more narrowly, not to favor a poor person in a dispute. More broadly, in Deuteronomy 10:17, Moses told that God shows no partiality among persons. Among the prophets, in Malachi 2:9, the prophet quoted God as saying that the people had not kept God's ways when they showed partiality in the law, and in the writings, Psalm 82:2 asks, "How long will you judge unjustly, and show favor to the wicked?" Proverbs 18:5 counsels that it is not good to show partiality to the wicked, so as to turn aside the righteous in judgment. Similarly, Proverbs 24:23 and 28:21 say that to show partiality is not good. 2 Chronicles 19:7 reports that God has no iniquity or favoritism.

Deuteronomy 16:22 addresses the practice of setting up a baetyl (מַצֵּבָה, matzeivah). In Genesis 28:18, Jacob took the stone on which he had slept, set it up as a baetyl (מַצֵּבָה, matzeivah), and poured oil on the top of it. Exodus 23:24 later directed the Israelites to break in pieces the Canaanites' baetyls (מַצֵּבֹתֵיהֶם, matzeivoteihem). Leviticus 26:1 directed the Israelites not to rear up a baetyl and Deuteronomy 16:22 prohibited them from setting up a baetyl, "which the Lord your God hates."

Deuteronomy chapter 17

The Torah addresses the need for corroborating witnesses three times: Numbers 35:30 instructs that a manslayer may be executed only on the evidence of two or more witnesses. Deuteronomy 17:6 states the same multiple witness requirement for idolatry and all capital cases, and Deuteronomy 19:15 applies the rule to all criminal offenses. Deuteronomy 13:9 and 17:7 both state that the witnesses verifying wrongful worship of other gods shall also be the first to carry out the death sentence.[61]

Deuteronomy 17:9 assigns "the priests, the Levites" a judicial role. The Levites' role as judges also appears in Chronicles and Nehemiah.[62] The Hebrew Bible also assigns to the Levites the duties of teaching the law,[63] ministering before the Ark,[64] singing,[65] and blessing God's Name.[66]

Deuteronomy 17:14–20 sets out rules for kings. In 1 Samuel 8:10–17, the prophet Samuel warned what kings would do. The king would take the Israelites' sons to be horsemen, to serve with the king's chariots, to serve as officers, to plow the king's ground, to reap the harvest, and to make chariots and other instruments of war. The king would take the Israelites' daughters to be perfumers, cooks, and bakers. The king would take the Israelites' fields, vineyards, and olive yards and give them to his servants. The king would take the tenth part of the Israelites' seed, grapes, and flocks. The king would take the Israelites' servants and donkeys and put them to his work. The Israelites would be the king's servants.

Deuteronomy 17:16–17 teaches that the king was not to keep many horses, marry many wives, or amass excess silver and gold. 1 Kings 10:14–23, however, reports that King Solomon accumulated riches exceeding all the kings of the earth, and that he received 660 talents — about 20 tons — of gold every year, in addition to that which came in taxes from the merchants, traders, and governors of the country. 1 Kings 10:24–26 reports that all the earth brought horses and mules to King Solomon, and he gathered together 1,400 chariots and 12,000 horsemen. 1 Kings 11:3 reports that King Solomon had 700 wives and 300 concubines, and his wives turned away his heart.

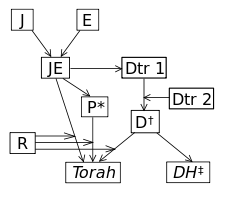

According to Deuteronomy 17:16, God has said that the Israelites "must not pass that way (i.e. to Egypt) again". There is no specific text elsewhere in the Torah where this statement is recorded, but Samuel Driver suggested that "these actual words were still read in some part of the narrative of JE, extant at the time when Deuteronomy was composed’.[67]

Deuteronomy chapter 18

The law in Deuteronomy 18:6-8, establishing that the rural Levites who came to Jerusalem were equal in rank and privilege with their fellow-tribesmen already ministering there, was not carried out during Josiah's religious reforms. 2 Kings 23:9 states that when Josiah "brought all the priests from the cities of Judah, and defiled the high places where the priests had burned incense, from Geba to Beersheba, the priests of the high places came not up to the altar of Jehovah at Jerusalem but they did eat unleavened bread among their brethren". The Pulpit Commentary explains that this was because "their participation in a semi-idolatrous service had disqualified them for the temple ministrations".[68]

Deuteronomy 18:16 refers back directly to Deuteronomy 5:21, but in Deuteronomy 5:21 the language is communal:

- "Now therefore why should we die? for this great fire will consume us; if we hear the voice of the LORD our God any more, then we shall die",

whereas the Israelites' anxiety is expressed in Deuteronomy 18:16 in a single voice:

- "Let me not hear again the voice of the LORD my God, neither let me see this great fire any more, that I die not."

Deuteronomy chapter 19

The provisions for responding to a false witness in Deuteronomy 19:16–19 reflect the commandment given in Deuteronomy 5:20:

- "You shall not bear false witness against your neighbor".

Torah sets forth the law of "an eye for an eye" in three separate places: Exodus 21:22–25; Leviticus 24:19–21; and Deuteronomy 19:21.

In early nonrabbinic interpretation

The parashah has parallels or is discussed in these early nonrabbinic sources:[69]

Deuteronomy chapter 17

Philo called the rule that a judge should not receive the testimony of a single witness "an excellent commandment." Philo argued first that a person might inadvertently gain a false impression of a thing or be careless about observing and therefore be deceived. Secondly, Philo argued it unjust to trust to one witness against many persons, or indeed against only one individual, for why should the judge trust a single witness testifying against another, rather than the defendant pleading on the defendant's own behalf? Where there is no preponderance of opinion for guilt, Philo argued, it is best to suspend judgment.[70]

Similarly, Josephus reported the rule of Deuteronomy 17:6 and 19:15, writing that judges should not credit a single witness, but rather should rely only on three, or two at the least, and only those whose testimony was confirmed by their good lives.[71]

Deuteronomy chapter 19

In the Gospel of Matthew, Jesus quoted approvingly the requirement for two witnesses in Deuteronomy 19:15 to advise followers how to confront a fellow believer who had sinned against them.[72] Similarly, in his Second Epistle to the Corinthians, Paul quoted approvingly the requirement for two or three witnesses to open a discussion of his forthcoming third visit to Corinth.[73]

Deuteronomy chapter 20

Paraphrasing Deuteronomy 20:10, Josephus reported that Moses told the Israelites that when they were about to go to war, they should send emissaries and heralds to those whom they had chosen to make enemies, for it was right to make use of words before weapons of war. The Israelites were to assure their enemies that although the Israelites had a numerous army, horses, weapons, and, above these, a merciful God ready to assist them, they nonetheless desired their enemies not to compel the Israelites to fight against them or to take from them what they had. And if the enemies heeded the Israelites, it would be proper for the Israelites to keep peace with the enemies. But if the enemies trusted in their own strength as superior to that of the Israelites and would not do the Israelites justice, then the Israelites were to lead their army against the enemies, making use of God as their supreme Commander.[74]

In classical rabbinic interpretation

The parashah is discussed in these rabbinic sources from the era of the Mishnah and the Talmud:[75]

Deuteronomy chapter 16

Tractate Sanhedrin in the Mishnah, Tosefta, Jerusalem Talmud, and Babylonian Talmud interpreted the laws of judges in Deuteronomy 16:18–20.[76] The Mishnah described three levels of courts: courts of 3 judges, courts of 23 judges, and a court of 71 judges, called the Great Sanhedrin.[77] Courts of three judges heard cases involving monetary disputes, larceny, bodily injury (as in Leviticus 24:19), claims for full or half damages as for damage done by a goring ox (described in Exodus 21:35), the repayment of the double (as in Exodus 23:3) or four- or five-fold restitution of stolen goods (as in Exodus 21:37), rape (as in Deuteronomy 22:28–29), seduction (as in Exodus 22:15–16),[78] flogging (as in Deuteronomy 25:2–3, although in the name of Rabbi Ishmael it was said that cases involving flogging were heard by courts of 23), the determination that a new month had begun (as in Exodus 12:2),[79] the performance of chalizah (as in Deuteronomy 25:5–10), and a woman's refusal of an arranged marriage.[80] Courts of 23 judges heard cases involving capital punishment, persons or beasts charged with unnatural intercourse (as in Leviticus 20:15–16), an ox that gored a person (as in Exodus 21:28), and wolves, lions, bears, leopards, hyenas, or snakes that killed a person. (Eliezer ben Hurcanus said that whoever killed such an animal, even without a trial, acquired merit, but Rabbi Akiva held that their death was to be decided by a court of 23.)[81] A court of 71 heard cases involving a tribe that had gone astray after idol-worship, a false prophet (as in Deuteronomy 18:20), a High Priest, optional war (that is, all wars apart from the conquest of Canaan), additions to the city of Jerusalem or the Temple courtyards, institution of small sanhedrins (of 23) for the tribes, and condemnation of a city (as in Deuteronomy 13:13).[82]

Rabbi Meir taught that courts of three judges heard defamation cases (as in Deuteronomy 22:14–21), but the Sages held that libel cases required a court of 23, as they could involve a capital charge (for if they found the woman guilty, Deuteronomy 22:21 required that they stone her).[78] Rabbi Meir taught that courts of three judges determined whether intercalation of an additional month to the year was needed, but Rabban Simeon ben Gamliel said that the matter was initiated by three, discussed by five, and determined by seven. The Mishnah held that if, however, it had been determined by only three, the determination held good.[79] Simeon bar Yochai taught that courts of three judges performed the laying of the elders' hands on the head of a communal sacrifice (as in Leviticus 4:15) and the breaking of the heifer's neck (as in Deuteronomy 21:1–9), but Judah bar Ilai said courts of five judges did so. The Mishnah taught that three experts were required for the assessment of fourth-year fruit (as in Leviticus 19:23–25) and the second tithe (as in Deuteronomy 14:22–26) of unknown value, of consecrated objects for redemption purposes, and valuations of movable property the value of which had been vowed to the Sanctuary. According to Judah bar Ilai, one of them had to be a kohen. The Mishnah taught that 10 including a kohen were required in the case of valuation of real estate or a person.[80]

Citing Proverbs 21:3, "To do righteousness and justice is more acceptable to the Lord than sacrifice," a midrash taught that God told David that the justice and the righteousness that he did were more beloved to God than the Temple. The midrash noted that Proverbs 21:3 does not say, "As much as sacrifice," but "More than sacrifice." The midrash explained that sacrifices were operative only so long as the Temple stood, but righteousness and justice hold good even when the Temple no longer stands.[83]

Simeon ben Halafta told that once an ant dropped a grain of wheat, and all the ants came and sniffed at it, yet not one of them took it, until the one to whom it belonged came and took it. Simeon ben Halafta praised the ant's wisdom and praiseworthiness, inasmuch as the ant had not learned its ways from any other creature and had no judge or officer to guide it, as Proverbs 6:6–7 says, the ant has "no chief, overseer, or ruler." How much more should people, who have judges and officers, hearken to them. Hence, Deuteronomy 16:18 directs appointment of judges in all the Israelites' cities.[84]

Shimon ben Lakish deduced from the proximity of the discussions of appointment of judges in Deuteronomy 16:18 and the Canaanite idolatrous practice of the Asherah in Deuteronomy 16:21 that appointing an incompetent judge is as though planting an idolatrous tree. Rav Ashi said that such an appointment made in a place where there were scholars is as though planting the idolatrous tree beside the Altar, for Deuteronomy 16:21 concludes "beside the altar of the Lord your God."[85] Similarly, Rav Ashi interpreted the words of Exodus 20:20, "You shall not make with Me gods of silver or gods of gold," to refers to judges appointed because of silver or gold.[86]

The Sifre interpreted the words "You shall not judge unfairly" in Deuteronomy 16:19 to mean that one should not say "So-and-so is impressive" or "Such-and-such is my relative." The Sifre interpreted the words "you shall show no partiality" in Deuteronomy 16:19 to mean that one should not say "So-and-so is poor" or "Such-and-such is rich."[87]

The Sifre interpreted the words "Justice, justice shall you pursue" in Deuteronomy 16:20 to teach that if a defendant has departed from a court with a judgment of innocence, the court has no right to call the defendant back to impose a judgment of guilt. And if a defendant has departed from a court with a judgment of guilt, the court does still have the ability to call the defendant back to reach a judgment of innocence.[88] Alternatively, the Sifre interpreted the words "Justice, justice shall you pursue" in Deuteronomy 16:20 to teach that one should seek a court that give well-construed rulings.[89] Similarly, the Rabbis taught in a Baraita that the words "Justice, justice shall you pursue" mean that one should pursue the most respected jurist to the place where the jurist holds court. The Rabbis also taught a Baraita that the words "Justice, justice shall you pursue" meant that one should follow sages to their academies.[90]

Shimon ben Lakish contrasted Leviticus 19:15, "In justice shall you judge your neighbor," with Deuteronomy 16:20, "Justice, justice shall you pursue," and concluded that Leviticus 19:15 referred to an apparently genuine claim, while Deuteronomy 16:20 referred to the redoubled scrutiny appropriate to a suit that one suspected to be dishonest. Rav Ashi found no contradiction, however, between the two verses, for a Baraita taught that in the two mentions of "justice" in Deuteronomy 16:20, one mention referred to a decision based on strict law, while the other referred to compromise. For example, where two boats meet on a narrow river headed in opposite directions, if both attempted to pass at the same time, both would sink, but if one made way for the other, both could pass without mishap. Similarly, if two camels met on the ascent to Bethoron, if they both ascended at the same time, both could fall into the valley, but if they ascended one after another, both could ascend safely. These were the principles by which the travelers were to resolve their impasse: If one was loaded and the other unloaded, then the unloaded was to give way to the loaded. If one was nearer to its destination than the other, then the nearer was to give way to the farther. If they were equally near to their destinations, then they were to compromise and the one that went first was to compensate the one who gave way.[91]

The Mishnah taught that the words of Jeremiah 17:7, "Blessed is the man who trusts in the Lord and whose hope is the Lord," apply to a judge who judges truly and with integrity. The Mishnah taught that the words of Deuteronomy 16:20, "Righteousness, righteousness shall you pursue," apply to tell that an able-bodied person who feigned to be disabled would become disabled. Similarly, the words of Exodus 23:8, "And a gift shall you not accept; for a gift blinds them that have sight," apply to tell that a judge who accepted a bribe or who perverted justice would become poor of vision.[92]

Reading the words "that you may thrive and occupy the land that the Lord your God is giving you" in Deuteronomy 16:20, the Sifre taught that the appointment of judges is of such importance that it could lead to the resurrection of Israel, their settlement in the Land of Israel, and their protection from being destroyed by the sword.[93]

Samuel ben Nahman taught in the name of Rabbi Jonathan that when a judge unjustly takes the possessions of one and gives them to another, God takes that judge's life, as Proverbs 22:22–23 says: "Rob not the poor because he is poor; neither oppress the afflicted in the gate, for the Lord will plead their cause, and will despoil of life those that despoil them." Samuel bar Nahman also taught in the name of Rabbi Jonathan that judges should always think of themselves as if they had a sword hanging over them and Gehenna gaping under them, as Song of Songs 3:7–8 says: "Behold, it is the litter of Solomon; 60 mighty men are about it, of the mighty men of Israel. They all handle the sword, and are expert in war; every man has his sword upon his thigh, because of dread in the night." Rabbi Josiah (or others say Rav Nachman bar Yitzchak) interpreted the words, "O house of David, thus says the Lord: 'Execute justice in the morning and deliver the spoiled out of the hand of the oppressor,'" in Jeremiah 21:12 to mean that judges should render judgment only if the judgment that they are about to give is as clear to them as the morning light.[94]

The Sifre deduced from the words "You shall not plant an Asherah of any kind of tree beside the altar of the Lord your God" in Deuteronomy 16:21 that planting a tree on the Temple Mount would violate a commandment.[95] Rabbi Eliezer ben Jacob deduced from the prohibition against any kind of tree beside the altar in Deuteronomy 16:21 that wooden columns were not allowed in the Temple courtyard.[96] The ‘’Gemara’’ explained that it was not permitted to build with wood near the altar. Rav Chisda, however, taught that baetyls were permitted.[97]

Reading the prohibition of baetyls in Deuteronomy 16:22, the Sifre noted that the baetyl esteemed by the Patriarchs was despised by their descendants.[98]

Deuteronomy chapter 17

The Mishnah questioned why Deuteronomy 17:6 discussed three witnesses, when two witnesses were sufficient to establish guilt. The Mishnah deduced that the language of Deuteronomy 17:6 meant to analogize between a set of two witnesses and a set of three witnesses. Just as three witnesses could discredit two witnesses, two witnesses could discredit three witnesses. The Mishnah deduced from the multiple use of the word "witnesses" in Deuteronomy 17:6 that two witnesses could discredit even a hundred witnesses. Rabbi Simeon deduced from the multiple use of the word "witnesses" in Deuteronomy 17:6 that just as two witnesses were not executed as perjurers until both had been incriminated, so three were not executed until all three had been incriminated. Rabbi Akiva deduced that the addition of the third witness in Deuteronomy 17:6 was to teach that the perjury of a third, superfluous witness was just as serious as that of the others. Rabbi Akiva concluded that if Scripture so penalized an accomplice just as one who committed a wrong, how much more would God reward an accomplice to a good deed. The Mishnah further deduced from the multiple use of the word "witnesses" in Deuteronomy 17:6 that just as the disqualification of one of two witnesses would invalidate the evidence of the set of two witnesses, so would the disqualification of one witness invalidate the evidence of even a hundred. Jose ben Halafta said that these limitations applied only to witnesses in capital charges, and that in monetary suits, the balance of the witnesses could establish the evidence. Judah the Prince said that the same rule applied to monetary suits or capital charges where the disqualified witnesses joined to take part in the warning of the defendant, but the rule did not disqualify the remaining witnesses where the disqualified witnesses did not take part in the warning. The Gemara further qualified the Mishnah's ruling.[99]

The Gemara cited the Torah's requirement for corroborating witnesses in Deuteronomy 17:6 to support the Mishnah's prohibition of circumstantial evidence in capital cases. The Mishnah reported that they admonished witnesses in capital cases not to testify based on conjecture (that is, circumstantial evidence) or hearsay, for the court would scrutinize the witnesses' evidence by cross-examination and inquiry.[100] The Gemara reported that the Rabbis taught that the words "based on conjecture" in the Mishnah meant that the judge told the witness that if the witness saw the defendant running after the victim into a ruin, and the witness pursued the defendant and found the defendant with bloody sword in hand and the victim writhing in agony, then the judge would tell the witness that the witness saw nothing (and did not actually witness a murder). It was taught in a Baraita that Rabbi Simeon ben Shetach said that he once did see a man pursuing his fellow into a ruin, and when Rabbi Simeon ben Shetach ran after the man and saw him, bloody sword in hand and the murdered man writhing, Rabbi Simeon ben Shetach exclaimed to the man, "Wicked man, who slew this man? It is either you or I! But what can I do, since your blood (that is, life) does not rest in my hands, for it is written in the Torah (in Deuteronomy 17:6) 'At the mouth of two witnesses . . . shall he who is to die be put to death'? May He who knows one's thoughts (that is, God) exact vengeance from him who slew his fellow!" The Gemara reported that before they moved from the place, a serpent bit the murderer and he died.[101]

The Gemara read the Torah's requirement for corroborating witnesses to limit the participation of witnesses and Rabbinical students in trials. The Mishnah taught that in monetary cases, all may argue for or against the defendant, but in capital cases, all may argue in favor of the defendant, but not against the defendant.[102] The Gemara asked whether the reference to "all" in this Mishnah included even the witnesses. Jose b. Judah and the Rabbis disagreed to some degree. The Gemara read the words of Numbers 35:30, "But one witness shall not testify against any person," to indicate that a witness cannot participate in a trial — either for acquittal or condemnation — beyond providing testimony. Jose b. Judah taught that a witness could argue for acquittal, but not for condemnation. Rav Papa taught that the word "all" means to include not the witnesses, but the Rabbinical students who attended trials, and thus was not inconsistent with the views of Jose b. Judah or of the Rabbis. The Gemara explained the reasoning of Jose b. Judah for his view that witnesses may argue in favor of the accused as follows: Numbers 35:30 says, "But one witness shall not testify against any person that he die." Hence, according to the reasoning of Jose b. Judah, only "so that he die" could the witness not argue, but the witness could argue for acquittal. Shimon ben Lakish explained the reasoning of the Rabbis forbidding a witness to argue in favor of the accused as follows: the Rabbis reasoned that if a witness could argue the case, then the witness might seem personally concerned in his testimony (for a witness contradicted by subsequent witnesses could be subject to execution for testifying falsely). The Gemara then asked how the Rabbis interpreted the words, "so that he die" (which seems to indicate that the witness may not argue only when it leads to death). The Gemara explained that the Rabbis read those words to apply to the Rabbinical students (constraining the students not to argue for condemnation). A Baraita taught that they did not listen to a witnesses who asked to make a statement in the defendant's favor, because Numbers 35:30 says, "But one witness shall not testify." They did not listen to a Rabbinical student who asked to argue a point to the defendant's disadvantage, because Numbers 35:30 says, "One shall not testify against any person that he die" (but a student could do so for acquittal).[103]

Rabbi Jose said that a malefactor was never put to death unless two witnesses had duly pre-admonished the malefactor, as Deuteronomy 17:6 prescribes, “At the mouth of two witnesses or three witnesses shall he that is worthy of death be put to death.” And the Mishnah reported another interpretation of the words, “At the mouth of two witnesses,” was that the Sanhedrin would not hear evidence from the mouth of an interpreter.[104]

Rav Zutra bar Tobiah reported that Rav reasoned that Deuteronomy 17:6 disqualified isolated testimony when it prescribes that “at the mouth of one witness he shall not be put to death.” This special admonition against one witness would seem redundant to the earlier context, “At the mouth of two witnesses or three witnesses shall he that is worthy of death be put to death,” so it was taken to mean that individual witnesses who witnesses the crime, one by one, in isolation from each other, were insufficient to convict. Similarly, a Baraita taught that Deuteronomy 17:6 prescribes, “At the mouth of one witness he shall not be put to death,” to cover instances where two persons see the wrongdoer, one from one window and the other from another window, without seeing each other, in which case the evidence could not be joined to form a set of witnesses sufficient to convict. Even if they both witnessed the offence from the same window, one after the other, their testimony could not be joined to form a set of witnesses sufficient to convict.[105]

Rabbi Ishmael the son of Rabbi Jose commanded Rabbi Judah the Prince not to engage in a lawsuit against three parties, for one would be an opponent and the other two would be witnesses for the other side.[106]

The Rabbis explained that God commanded Moses to carve two Tablets in Deuteronomy 10:1 because the two Tablets were to act as witnesses between God and Israel. The two Tablets corresponded to the two witnesses whom Deuteronomy 17:6 and 19:15 require to testify to a cause, to two groomsmen,[107] to bridegroom and bride, to heaven and earth, to this world and the world to come.[108]

Who were the judges in the court described in Deuteronomy 17:9? The Mishnah taught that the High Priest could serve as a judge.[109] But the King could not.[110] When a vacancy arose, a new judge was appointed from the first row of scholars who sat in front of the judges.[111]

Rav Joseph reported that a Baraita interpreted the reference to "the priests" in Deuteronomy 17:9 to teach that when the priests served in the Temple, a judge could hand down capital punishment, but when the priesthood is not functioning, the judge may not issue such judgments.[112]

Deuteronomy 17:9 instructs, "you shall come . . . to the judge who shall be in those days," but how could a person go to a judge who was not in that person's days? The Rabbis taught in a Baraita that Deuteronomy 17:9 employs the words "who shall be in those days" to show that one must be content to go to the judge who is in one's days, and accept that judge's authority. The Rabbis taught that Ecclesiastes 7:10 conveys a similar message when it says, "Say not, 'How was it that the former days were better than these?'"[113]

The Sages based their authority to legislate rules equally binding with those laid down in the Torah on the words of Deuteronomy 17:11: "According to the law that they shall teach you . . . you shall do; you shall not turn aside from the sentence that they shall declare to you."[114]

The Mishnah recounted a story that demonstrated the authority of the court in Deuteronomy 17:11 — that one must follow the rulings of the court and "not turn . . . to the right hand, nor to the left." After two witnesses testified that they saw the new moon at its proper time (on the thirtieth day of the month shortly before nightfall), Rabban Gamaliel (the president of the Great Sanhedrin in Jerusalem) accepted their evidence and ruled that a new month had begun. But later at night (after the nightfall with which the thirty-first day of the earlier month would have begun), when the new moon should have been clearly visible, no one saw the new moon. Rabbi Dosa ben Harkinas declared the two witnesses to be false witnesses, comparing their testimony to that of witnesses who testify that a woman bore a child, when on the next day her belly was still swollen. Rabbi Joshua told Rabbi Dosa that he saw the force of his argument. Rabban Gamaliel then ordered Rabbi Joshua to appear before Rabban Gamaliel with his staff and money on the day which according to Rabbi Joshua's reckoning would be Yom Kippur. (According to Rabbi Joshua's reckoning, Yom Kippur would fall a day after the date that it would fall according to Rabban Gamaliel's reckoning. And Leviticus 16:29 prohibited carrying a staff and money on Yom Kippur.) Rabbi Akiva then found Rabbi Joshua in great distress (agonizing over whether to obey Rabban Gamaliel's order to do what Rabbi Joshua considered profaning Yom Kippur). Rabbi Akiva told Rabbi Joshua that he could prove that whatever Rabban Gamaliel ordered was valid. Rabbi Akiva cited Leviticus 23:4, which says, "These are the appointed seasons of the Lord, holy convocations, which you shall proclaim in their appointed seasons," which is to say that whether they are proclaimed at their proper time or not, God has no appointed seasons other than those that are proclaimed. Rabbi Joshua then went to Rabbi Dosa, who told Rabbi Joshua that if they called into question the decisions of the court of Rabban Gamaliel, then they would have to call into question the decisions of every court since the days of Moses. For Exodus 24:9 says, "Then Moses and Aaron, Nadab and Abihu, and 70 of the elders of Israel went up," and Exodus 24:9 does not mention the names of the elders to show that every group of three that has acted as a court over Israel is on a level with the court of Moses (as most of the members of that court also bore names without distinction). Rabbi Joshua then took his staff and his money and went to Rabban Gamaliel on the day that Rabbi Joshua reckoned was Yom Kippur. Rabban Gamaliel rose and kissed Rabbi Joshua on his head and said, "Come in peace, my teacher and my disciple — my teacher in wisdom and my disciple because you have accepted my decision."[115]

The Mishnah explained the process by which one was found to be a rebellious elder within the meaning of Deuteronomy 17:12. Three courts of law sat in Jerusalem: one at the entrance to the Temple Mount, a second at the door of the Temple Court, and the third, the Great Sanhedrin, in the Hall of Hewn Stones in the Temple Court. The dissenting elder and the other members of the local court with whom the elder disputed went to the court at the entrance to the Temple Mount, and the elder stated what the elder and the elder's colleagues expounded. If the first court had heard a ruling on the matter, then the court stated it. If not, the litigants and the judges went to the second court, at the entrance of the Temple Court, and the elder once again declared what the elder and the elder's colleagues expounded. If this second court had heard a ruling on the matter, then this court stated it. If not, then they all proceeded to the Great Sanhedrin at the Hall of Hewn Stones, which issued instruction to all Israel, for Deuteronomy 17:10 said that "they shall declare to you from that place that the Lord shall choose," meaning the Temple. If the elder then returned to the elder's town and issued a decision contrary to what the Great Sanhedrin had instructed, then the elder was guilty of acting "presumptuously" within the meaning of Deuteronomy 17:12. But if one of the elder's disciples issued a decision opposed to the Great Sanhedrin, the disciple was exempt from judgment, for the very stringency that kept the disciple from having yet been ordained served as a source of leniency to prevent the disciple from being found to be a rebellious elder.[116]

Rules for kings

Mishnah Sanhedrin 2:4–5 and Babylonian Talmud Sanhedrin 20b–22b interpreted the laws governing the king in Deuteronomy 17:14–20.[117]

The Mishnah taught that the king could lead the army to a voluntary war on the decision of a court of 71. He could force a way through private property, and none could stop him. There was no limit to the size of the king's road. And he had first choice of the plunder taken by the people in war.[118]

The Rabbis disagreed about the powers of the king. The Gemara reported that Judah bar Ezekiel said in Samuel of Nehardea’s name that a king was permitted to take all the actions that 1 Samuel 8:4–18 enumerated, but Abba Arika said that 1 Samuel 8 was intended only to frighten the people, citing the emphatic double verb in the words "You shall surely set a king over you" in Deuteronomy 17:15 to indicate that the people would fear the king. The Gemara also reported the same dispute among other Tannaim; in this account, Rabbi Jose said that a king was permitted to take all the actions that 1 Samuel 8:4–18 enumerated, but Rabbi Judah said that 1 Samuel 8 was intended only to frighten the people, citing the emphatic double verb in the words "You shall surely set a king over you" in Deuteronomy 17:15 to indicate that the people would fear the king. Rabbi Judah (or others say Rabbi Jose) said that three commandments were given to the Israelites when they entered the land: (1) the commandment of Deuteronomy 17:14–15 to appoint a king, (2) the commandment of Deuteronomy 25:19 to blot out Amalek, and (3) the commandment of Deuteronomy 12:10–11 to build the Temple in Jerusalem. Rabbi Nehorai, on the other hand, said that Deuteronomy 17:14–15 did not command the Israelites to choose a king, but was spoken only in anticipation of the Israelites' future complaints, as Deuteronomy 17:14 says, "And (you) shall say, 'I will set a king over me.'"[119]

The Mishnah taught that the king could neither judge nor be judged, testify nor be testified against. The king could not perform the ceremony to decline Levirate marriage (חליצה, chalizah) nor could the ceremony be performed to his wife. The king could not perform the duty of a brother in Levirate marriage (יבום, yibbum), nor could that duty be performed to his wife. Rabbi Judah taught that if the king wished to perform halizah or yibbum, he would be remembered for good. But the rabbis taught that even if he wished to do so, he was not listened to, and no one could marry his widow. Rabbi Judah taught that a king could marry a king's widow, for David married the widow of Saul, as 2 Samuel 12:8 reports, "And I gave you your master's house and your master's wives to your bosom."[120]

Deuteronomy 17:15 says that "the Lord your God shall choose" the Israelite king. Hanan bar Rava said in the name of Rav that even the superintendent of a well is appointed in Heaven, as 1 Chronicles 29:11 says that God is "sovereign over every leader."[121]

The Mishnah interpreted the words "He shall not multiply horses to himself" in Deuteronomy 17:16 to limit the king to only as many horses as his chariots required.[122]

The Mishnah interpreted the words "Neither shall he multiply wives to himself" in Deuteronomy 17:17 to limit him to no more than 18 wives. Judah said that he could have more wives, provided that they did not turn away his heart. But Simeon said that he must not marry even one wife who would turn away his heart. The Mishnah concluded that Deuteronomy 17:17 prohibited the king from marrying more than 18 wives, even if they were all as righteous as Abigail the wife of David.[123] The Gemara noted that Judah did not always employ the rationale behind a Biblical passage as a basis for limiting its legal effect, as he did here in Mishnah Sanhedrin 2:4. The Gemara explained that Rabbi Judah employed the rationale behind the law here because Deuteronomy 17:17 itself expounds the rationale behind its legal constraint: The reason behind the command, "he shall not multiply wives to himself," is so "that his heart be not turned aside." Thus Rabbi Judah reasoned that Deuteronomy 17:17 itself restricts the law to these conditions, and a king could have more wives if "his heart be not turned aside." The Gemara noted that Simeon did not always interpret a Biblical passage strictly by its plain meaning, as he appeared to do here in Mishnah Sanhedrin 2:4. The Gemara explained that Simeon could have reasoned that Deuteronomy 17:17 adds the words, "that his heart turn not away," to imply that the king must not marry even a single wife who might turn away his heart. And one could interpret the words "he shall not multiply" to mean that the king must not marry many wives even if they, like Abigail, would never turn away his heart. The Gemara then analyzed how the anonymous first view in Mishnah Sanhedrin 2:4 came to its conclusion that the king could have no more than 18 wives. The Gemara noted that 2 Samuel 3:2–5 refers to the children of six of David's wives born to David in Hebron. The Gemara reasoned that the prophet Nathan referred to these six wives in 2 Samuel 12:8 when he said, "And if that were too little, then would I add to you the like of these, and the like of these," each "these" implying six more wives. Thus with the original six, these two additions of six would make 18 in all.[124]

The Mishnah interpreted the words "and silver and gold he shall not greatly multiply to himself" in Deuteronomy 17:17 to limit the king to only as much silver and gold as he needed to pay his soldiers.[122]

The Mishnah interpreted the words "he shall write a copy of this law in a book" in Deuteronomy 17:18 to teach that when he went to war, he was to take it with him; on returning, he was to bring it back; when he sat in judgment, it was to be with him; and when he sat down to eat, it was to be before him, to fulfill the words of Deuteronomy 17:19, "and it shall be with him and he shall read in it all the days of his life."[125]

Deuteronomy chapter 18

Rules for Levites

The interpreters of Scripture by symbol taught that the deeds of Phinehas explained why Deuteronomy 18:3 directed that the priests were to receive the foreleg, cheeks, and stomach of sacrifices. The foreleg represented the hand of Phinehas, as Numbers 25:7 reports that Phinehas "took a spear in his hand." The cheeks' represent the prayer of Phinehas, as Psalm 106:30 reports, "Then Phinehas stood up and prayed, and so the plague was stayed." The stomach was to be taken in its literal sense, for Numbers 25:8 reports that Phinehas "thrust . . . the woman through her belly."[126]

Rules for prophets

Mishnah Sanhedrin 7:7 and Babylonian Talmud Sanhedrin 64a–b interpreted the laws prohibiting passing one's child through the fire to Molech in Leviticus 18:21 and 20:1–5, and Deuteronomy 18:10.[127]

_2.jpg)

Rabbi Assi taught that the children of Noah were also prohibited to do anything stated in Deuteronomy 18:10–11: "There shall not be found among you any one that makes his son or his daughter to pass through the fire, one that uses divination, a soothsayer, or an enchanter, or a sorcerer, or a charmer, or one that consults a ghost or a familiar spirit, or a necromancer."[128]

The Mishnah defined a "sorcerer" (מְכַשֵּׁף, mechashef) within the meaning of Deuteronomy 18:10 to be one who actually performed magic, in which case the sorcerer was liable to death. But if the offender merely created illusions, the offender was not put to death. Rabbi Akiva said in Rabbi Joshua's name that two may gather cucumbers by "magic," and one was to be punished and the other was to be exempt. The one who actually gathered the cucumbers by magic was to be punished, while the one who performed an illusion was exempt.[129]

Similarly, the Sifre defined the terms "augurer," "diviner," "soothsayer," and "sorcerer" within the meaning of Deuteronomy 18:10. An "augurer" was one who took hold of a staff and said, "Whether I should go or not." Rabbi Ishmael said that a "soothsayer" was someone who passed something over his eye. Rabbi Akiva said that soothsayers calculated the seasons, as did those who declared that the years prior to the seventh year produced good wheat or bad beans. The Sages said soothsayers were those who performed illusions. The Sifre defined "diviners" as people who said that something could be divined from, for example, bread falling from someone's mouth, a staff falling from someone's hand, a snake passing on one's right or a fox on one's left, a deer stopping on the way before someone, or the coming of the new moon. The Sifre taught that a "sorcerer" was someone who actually carried out a deed, not merely performing an illusion.[130]

Johanan bar Nappaha taught that sorcerers are called כַשְּׁפִים, kashefim, because they seek to contradict the power of Heaven. (Some read כַשְּׁפִים, kashefim, as an acronym for כחש פמליא, kachash pamalia, "contradicting the legion [of Heaven].") But the Gemara noted that Deuteronomy 4:35 says, "There is none else besides Him (God)." Rabbi Hanina interpreted Deuteronomy 4:35 to teach that even sorcerers have no power to oppose God's will. A woman once tried to take earth from under Rabbi Hanina's feet (so as to perform sorcery against him). Rabbi Hanina told her that if she could succeed in her attempts, she should go ahead, but (he was not concerned, for) Deuteronomy 4:35 says, "There is none else beside Him." But the Gemara asked whether Johanan bar Nappaha had not taught that sorcerers are called כַשְּׁפִים, kashfim, because they (actually) contradict the power of Heaven. The Gemara answered that Rabbi Hanina was in a different category, owing to his abundant merit (and therefore Heaven protected him).[131]

In Deuteronomy 18:15, Moses foretold that "A prophet will the Lord your God raise up for you, from your midst, of your brethren." The Sifre deduced from the words "for you" that God would not raise up a prophet for other nations. The Sifre deduced from the words "from your midst" that a prophet could not come from abroad. The Sifre deduced from the words "of your brethren" that a prophet could not be an outsider.[132]

In Deuteronomy 18:15, Moses foretold that "A prophet will the Lord your God raise up for you ... like me," and Johanan bar Nappaha thus taught that prophets would have to be, like Moses, strong, wealthy, wise, and meek. Strong, for Exodus 40:19 says of Moses, "he spread the tent over the tabernacle," and a Master taught that Moses himself spread it, and Exodus 26:16 reports, "Ten cubits shall be the length of a board." Similarly, the strength of Moses can be derived from Deuteronomy 9:17, in which Moses reports, "And I took the two tablets, and cast them out of my two hands, and broke them," and it was taught that the tablets were six handbreadths in length, six in breadth, and three in thickness. Wealthy, as Exodus 34:1 reports God's instruction to Moses, "Carve yourself two tablets of stone," and the Rabbis interpreted the verse to teach that the chips would belong to Moses. Wise, for Rav and Samuel both said that 50 gates of understanding were created in the world, and all but one were given to Moses, for Psalm 8:6 said of Moses, "You have made him a little lower than God." Meek, for Numbers 12:3 reports, "Now the man Moses was very meek."[133]

The Mishnah taught that the community was to execute a false prophet within the meaning of Deuteronomy 18:20 — one who prophesied what the prophet had not heard or what was not told to the prophet. But Heaven alone would see to the death of the person who suppressed a prophecy or disregarded the words of a prophet, or a prophet who transgressed the prophet's own word. For in Deuteronomy 18:19, God says, "I will require it of him."[134] The Mishnah taught that only a court of 71 members (the Great Sanhedrin) could try a false prophet.[135]

The Mishnah taught that the community was to execute by strangulation a false prophet and one who prophesied in the name of an idol.[136] The Mishnah taught that one who prophesied in the name of an idol was subject to execution by strangulation even if the prophecy chanced upon the correct law.[137]

A Baraita taught that prophecy died when the later prophets Haggai, Zechariah, and Malachi died, and the Divine Spirit departed from Israel. But Jews could still on occasion hear echoes of a Heavenly Voice (Bat Kol).[138]

Deuteronomy chapter 19

Cities of refuge

Chapter 2 of tractate Makkot in the Mishnah, Tosefta, Jerusalem Talmud, and Babylonian Talmud interpreted the laws of the cities of refuge in Exodus 21:12–14, Numbers 35:1–34, Deuteronomy 4:41–43, and 19:1–13.[139]

The Mishnah taught that those who killed in error went into banishment. One would go into banishment if, for example, while one was pushing a roller on a roof, the roller slipped over, fell, and killed someone. One would go into banishment if while one was lowering a cask, it fell down and killed someone. One would go into banishment if while coming down a ladder, one fell and killed someone. But one would not go into banishment if while pulling up the roller it fell back and killed someone, or while raising a bucket the rope snapped and the falling bucket killed someone, or while going up a ladder one fell down and killed someone. The Mishnah's general principle was that whenever the death occurred in the course of a downward movement, the culpable person went into banishment, but if the death did not occur in the course of a downward movement, the person did not go into banishment. If while chopping wood, the iron slipped from the ax handle and killed someone, Rabbi taught that the person did not go into banishment, but the sages said that the person did go into banishment. If from the split log rebounding killed someone, Rabbi said that the person went into banishment, but the sages said that the person did not go into banishment.[140]

Rabbi Jose bar Judah taught that to begin with, they sent a slayer to a city of refuge, whether the slayer killed intentionally or not. Then the court sent and brought the slayer back from the city of refuge. The Court executed whomever the court found guilty of a capital crime, and the court acquitted whomever the court found not guilty of a capital crime. The court restored to the city of refuge whomever the court found liable to banishment, as Numbers 35:25 ordained, "The congregation shall restore him to the city of refuge from where he had fled."[141] Numbers 35:25 also says, "The manslayer . . . shall dwell therein until the death of the High Priest, who was anointed with the holy oil," but the Mishnah taught that the death of a High Priest who had been anointed with the holy anointing oil, the death of a High Priest who had been consecrated by the many vestments, or the death of a High Priest who had retired from his office each equally made possible the return of the slayer. Rabbi Judah said that the death of a priest who had been anointed for war also permitted the return of the slayer. Because of these laws, mothers of High Priests would provide food and clothing for the slayers in cities of refuge so that the slayers might not pray for the High Priest's death.[142] If the High Priest died at the conclusion of the slayer's trial, the slayer did not go into banishment. If, however, the High Priests died before the trial was concluded and another High Priest was appointed in his stead and then the trial concluded, the slayer returned home after the new High Priest's death.[143]

In Deuteronomy 19:6, the heart becomes hot, and in Deuteronomy 20:3, the heart grows faint. A Midrash catalogued the wide range of additional capabilities of the heart reported in the Hebrew Bible.[144] The heart speaks,[145] sees,[145] hears,[146] walks,[147] falls,[148] stands,[149] rejoices,[150] cries,[151] is comforted,[152] is troubled,[153] becomes hardened,[154] grieves,[155] fears,[156] can be broken,[157] becomes proud,[158] rebels,[159] invents,[160] cavils,[161] overflows,[162] devises,[163] desires,[164] goes astray,[165] lusts,[166] is refreshed,[167] can be stolen,[168] is humbled,[169] is enticed,[170] errs,[171] trembles,[172] is awakened,[173] loves,[174] hates,[175] envies,[176] is searched,[177] is rent,[178] meditates,[179] is like a fire,[180] is like a stone,[181] turns in repentance,[182] dies,[183] melts,[184] takes in words,[185] is susceptible to fear,[186] gives thanks,[187] covets,[188] becomes hard,[189] makes merry,[190] acts deceitfully,[191] speaks from out of itself,[192] loves bribes,[193] writes words,[194] plans,[195] receives commandments,[196] acts with pride,[197] makes arrangements,[198] and aggrandizes itself.[199]

Landmarks

Rabbi Hiyya bar Abba taught in Johanan bar Nappaha's name that the words of Deuteronomy 19:14, "You shall not remove your neighbor's landmark, which they of old have set," meant that when planting, one should not encroach upon the boundary that they of old set. (Thus, one should not plant so near to one's neighbor's border that one's plants' roots draw sustenance from the neighbor's land, thus impoverishing it.) The Gemara further cited this analysis for the proposition that one may rely on the Rabbis' agricultural determinations.[200]

The Sifre asked why Deuteronomy 19:14 says, "You shall not remove your neighbor's landmark," when Leviticus 19:13 already says, "You shall not rob." The Sifre explained that Deuteronomy 19:14 teaches that one who removes a neighbor's boundary mark violates two negative commandments. The Sifre further explained that lest one think that this conclusion applies outside the Land of Israel, Deuteronomy 19:14 says, "in your inheritance that you will inherit in the land," indicating that only in the Land of Israel would one violate two negative commandments. Outside the Land of Israel, one would violate only the one commandment of Leviticus 19:13, "You shall not rob." The Sifre further taught that one violates the command of Deuteronomy 19:14 not to move a neighbor's landmark (1) if one moves an Israelite's landmark, (2) if one substitutes the statement of Eliezer ben Hurcanus for that of Rabbi Joshua or vice versa, or (3) if one sells a burial plot purchased by an ancestor.[201]

The Mishnah taught that one who prevents the poor from gleaning, or allows one but not another to glean, or helps one poor person but not another to glean is deemed to be a robber of the poor. Concerning such a person Proverbs 22:28 said, "Remove not the landmark of those who came up."[202]

Rules for witnesses

Chapter 1 of tractate Makkot in the Mishnah, Tosefta, and Babylonian Talmud interpreted the laws of perjury in Deuteronomy 19:15–21.[203]

The Mishnah taught how they punished perjurers where they could not punish the perjurers with the punishment that the perjurers sought to inflict. If the perjurers testified that a priest was a son of a divorcee (thus disqualifying the son as a priest) or the son of a woman who had been declined in Levirate marriage (a woman who had received halizah, once again disqualifying the son as a priest), they did not order that each perjurer be stigmatized as born of a divorcee or a woman declined in Levirate marriage. Rather, they gave the perjurer 40 lashes. If the perjurers testified that a person was guilty of a charge punishable by banishment, they did not banish the perjurers. Rather, they gave the perjurer 40 lashes.[204]

The Mishnah taught that if perjurers testified that a man divorced his wife and had not paid her ketubah, seeing that her ketubah would ultimately have to be paid sooner or later, the assessment was made based on the value of the woman's ketubah in the event of her being widowed or divorced or, alternatively, her husband inheriting her after her death. If perjurers testified that a debtor owed a creditor 1,000 zuz due within 30 days, while the debtor says that the debt was due in 10 years, the assessment of the fine is made on the basis of how much one might be willing to offer for the difference between holding the sum of 1,000 zuz to be repaid in 30 days or in 10 years.[205]

If witnesses testified that a person owed a creditor 200 zuz, and the witnesses turned out to have perjured themselves, then Rabbi Meir taught that they flogged the perjurers and ordered the perjurers to pay corresponding damages, because Exodus 20:12 (20:13 in the NJPS) sanctions the flogging and Deuteronomy 19:19 sanctions the compensation. But the Sages said that one who paid damages was not flogged.[206]

If witnesses testified that a person was liable to receive 40 lashes, and the witnesses turned out to have perjured themselves, then Rabbi Meir taught that the perjurers received 80 lashes — 40 on account of the commandment of Exodus 20:12 (20:13 in the NJPS) not to bear false witness and 40 on account of the instruction of Deuteronomy 19:19 to do to perjurers as they intended to do to their victims. But the Sages said that they received only 40 lashes.[207]

The Mishnah taught that a group of convicted perjurers divided monetary penalties among themselves, but penalties of lashes were not divided among offenders. Thus if the perjurers testified that a person owed a friend 200 zuz, and they were found to have committed perjury, the court divided the damages proportionately among the perjurers. But if the perjurers testified that a person was liable to a flogging of 40 lashes, and they were found to have committed perjury, then each perjurer received 40 lashes.[208]

The Mishnah taught that they did not condemn witnesses as perjurers until other witnesses directly incriminated the first witnesses. Thus if the first witnesses testified that one person killed another, and other witnesses testified that the victim or the alleged murderer was with the other witnesses on that day in a particular place, then they did not condemn the first witnesses as perjurers. But if the other witnesses testified that the first witnesses were with the other witnesses on that day in a particular place, then they did condemn the first witnesses as perjurers and executed the first witnesses on the other witnesses' evidence.[209]

The Mishnah taught that if a second set of witnesses came and charged the first witnesses with perjury, and then a third set of witnesses came and charged them with perjury, even if a hundred witnesses did so, they were all to be executed. Rabbi Judah said that this demonstrated a conspiracy, and they executed only the first set of witnesses.[210]

The Mishnah taught that they did not execute perjurers in a capital case until after the conclusion of the trial of the person against whom they testified. The Sadducees taught that they executed perjurers only after the accused had actually been executed, pursuant to the injunction "eye for eye" in Deuteronomy 19:21. The (Pharisee) Sages noted that Deuteronomy 19:19 says, "then shall you do to him as he purposed to do to his brother," implying that his brother was still alive. The Sages thus asked what "life for life" meant. The Sages taught that one might have thought that perjurers were liable to be executed from the moment that they delivered their perjured testimony, so Deuteronomy 19:21 says "life for life" to instruct that perjurers were not to be put to death until after the conclusion of the trial.[211]

The Gemara taught that the words "eye for eye" in Deuteronomy 19:21 meant pecuniary compensation. Simeon bar Yochai asked those who would take the words literally how they would enforce equal justice where a blind man put out the eye of another man, or an amputee cut off the hand of another, or where a lame person broke the leg of another. The school of Rabbi Ishmael cited the words "so shall it be given to him" in Leviticus 24:20, and deduced that the word "give" could apply only to pecuniary compensation. The school of Rabbi Hiyya cited the words "hand for hand" in Deuteronomy 19:21 to mean that an article was given from hand to hand, namely money. Abaye reported that a sage of the school of Hezekiah taught that Exodus 21:23–24 said "eye for eye" and "life for life," but not "life and eye for eye," and it could sometimes happen that eye and life would be taken for an eye, as when the offender died while being blinded. Rav Papa said in the name of Rava that Exodus 21:19 referred explicitly to healing, and the verse would not make sense if one assumed that retaliation was meant. And Rav Ashi taught that the principle of pecuniary compensation could be derived from the analogous use of the term "for" in Exodus 21:24 in the expression "eye for eye" and in Exodus 21:36 in the expression "he shall surely pay ox for ox." As the latter case plainly indicated pecuniary compensation, so must the former.[212]

Deuteronomy chapter 20

Rules for war

Chapter 8 of tractate Sotah in the Mishnah and Babylonian Talmud and part of chapter 7 of tractate Sotah in the Tosefta interpreted the laws of those excused from war in Deuteronomy 20:1–9.[213]

The Mishnah taught that when the High Priest anointed for battle addressed the people, he spoke in Hebrew. The High Priest spoke the words "against your enemies" in Deuteronomy 20:3 to make clear that it was not against their brethren that the Israelites fought, and thus if they fell into the enemies' hands, the enemies would not have mercy on them. The High Priest said "let not your heart faint" in Deuteronomy 20:3 to refer to the neighing of the horses and the brandishing of swords. He said "fear not" in Deuteronomy 20:3 to refer to the crash of shields and the tramp of the soldiers' shoes. He said "nor tremble" in Deuteronomy 20:3 to refer to the sound of trumpets. He said "neither be afraid" in Deuteronomy 20:3 to refer to the sound of battle-cries. He said the words "for the Lord your God goes with you, to fight for you against your enemies, to save you" in Deuteronomy 20:4 to make clear that the enemies would come relying upon the might of flesh and blood, but the Israelites came relying upon the might of God. The High Priest continued, saying that the Philistines came relying upon the might of Goliath, and his fate was to fall by the sword, and the Philistines fell with him. The Ammonites came relying upon the might of their captain Shobach, but his fate was to fall by the sword, and the Ammonites fell with him. Thus the High Priest said the words of Deuteronomy 20:4 to allude to the camp of the Ark of the Covenant, which would go to battle with the Israelites.[214]

The Mishnah interpreted the words "fearful and fainthearted" within the meaning of Deuteronomy 20:8. Rabbi Akiva taught that one should understand "fearful and fainthearted" literally — the conscript was unable to stand in the battle-ranks and see a drawn sword. Rabbi Jose the Galilean, however, taught that the words "fearful and fainthearted" alluded to those who feared because of the transgressions that they had committed. Therefore, the Torah connected the fearful and fainthearted with those who had built a new house, planted a vineyard, or become engaged, so that the fearful and fainthearted might return home on their account. (Otherwise, those who claimed exemption because of sinfulness would have to expose themselves publicly as transgressors.) Rabbi Jose counted among the fearful and fainthearted a High Priest who married a widow, an ordinary priest who married a divorcee or a woman who had been declined in Levirate marriage (a woman who had received chalitzah), and a lay Israelite who married the child of an illicit union (a mamzer) or a Gibeonite.[215]

Rabbi Jose the Galilean taught that great is peace, since even in a time of war, one should begin with peace, as Deuteronomy 20:10, says, "When you draw near to a city to fight against it, then proclaim peace to it."[216] Similarly, reading Deuteronomy 20:10, a Midrash exclaimed how great the power of peace is, for God directed that we should offer peace even to antagonists. Thus the Sages taught that we must inquire about the welfare of other nations in order to keep the peace.[217]

Citing Deuteronomy 20:10, Rabbi Joshua of Siknin said in the name of Rabbi Levi that God agreed to whatever Moses decided. For in Deuteronomy 2:24, God commanded Moses to make war on Sihon, but Moses did not do so, but as Deuteronomy 2:26 reports, Moses instead “sent messengers.” God told Moses that even though God had commanded Moses to make war with Sihon and instead Moses began with peace, God would confirm Moses’ decision and decree that in every war upon which Israel entered, Israel must begin with an offer of peace, as Deuteronomy 20:10 says, “When you draw near to a city to fight against it, then proclaim peace to it.”[218]

Even though one might conclude from Deuteronomy 20:10 and 15–18 that the Israelites were not to offer peace to the Canaanites, Samuel bar Nachman taught that Joshua sent three edicts to the inhabitants of the Land of Israel before the Israelites entered the land: first, that whoever wanted to leave the land should leave; second, that whoever wished to make peace and agree to pay taxes should do so; and third, that whoever wished to make war should do so. The Girgashites vacated their land and thus merited receiving land in Africa. The Gibeonites made peace with the Israelites, as reported in Joshua 10:1.[219]

When the Israelites carried out the commandment of Deuteronomy 27:8, "You shall write upon the stones all the words of this law," Simeon taught that the Israelites inscribed the Torah on the plaster and wrote below (for the nations) the words of Deuteronomy 20:18, "That they teach you not to do after all their abominations." Simeon taught that if people of the nations then repented, they would be accepted. Rabbah b. Shela taught that Rabbi Simeon's reason for teaching that the Israelites inscribed the Torah on the plaster was because Isaiah 33:12 says, "And the peoples shall be as the burnings of plaster." That is, the people of the other nations would burn on account of the matter on the plaster (and because they failed to follow the teachings written on the plaster). Rabbi Judah, however, taught that the Israelites inscribed the Torah directly on the stones, as Deuteronomy 27:8 says, "You shall write upon the stones all the words of this law," and after that they plastered them over with plaster. Rabbi Simeon asked Rabbi Judah how then the people of that time learned the Torah (as the inscription would have been covered with plaster). Rabbi Judah replied that God endowed the people of that time with exceptional intelligence, and they sent their scribes, who peeled off the plaster and carried away a copy of the inscription. On that account, the verdict was sealed for them to descend into the pit of destruction, because it was their duty to learn Torah, but they failed to do so. Rabbi Judah explained Isaiah 33:12 to mean that their destruction would be like plaster: Just as there is no other remedy for plaster except burning (for burning is the only way to obtain plaster), so there was no remedy for those nations (who cleave to their abominations) other than burning.[220]

Deuteronomy chapter 21

The beginning of chapter 9 of tractate Sotah in the Mishnah, Tosefta, and Babylonian Talmud interpreted the laws of the found corpse and the calf whose neck was to be broken (עֶגְלָה עֲרוּפָה, egla arufa) in Deuteronomy 21:1–9.[221]

The Mishnah taught that they buried the heifer whose neck was broken pursuant to Deuteronomy 21:1–9.[222]

Eliezer ben Hurcanus ruled that the calf (עֶגְלָה, eglah) prescribed in Deuteronomy 21:3–6 had to be no more than one year old and the red cow (פָרָה, parah) prescribed in Numbers 19:2 had to be two years old. But the Sages ruled that the calf could be even two years old and the red cow could be three or four years old. Rabbi Meir ruled that the red cow could be even five years old, but they did not wait with an older cow, as it might in the meantime grow some black hairs and thus become invalid.[223]