Pinechas (parsha)

Pinechas, Pinchas, Pinhas, or Pin'has (פִּינְחָס — Hebrew for "Phinehas," a name, the sixth word and the first distinctive word in the parashah) is the 41st weekly Torah portion (פָּרָשָׁה, parashah) in the annual Jewish cycle of Torah reading and the eighth in the Book of Numbers. It constitutes Numbers 25:10–30:1. The parashah is made up of 7,853 Hebrew letters, 1,887 Hebrew words, and 168 verses, and can occupy about 280 lines in a Torah scroll (סֵפֶר תּוֹרָה, Sefer Torah).[1]

Jews generally read it in July, or rarely in late June or early August.[2] As the parashah sets out laws for the Jewish holidays, Jews also read parts of the parashah as Torah readings for many Jewish holidays. Numbers 28:1–15 is the Torah reading for the New Moon (ראש חודש, Rosh Chodesh) on a weekday (including when the sixth or seventh day of Hanukkah falls on Rosh Chodesh). Numbers 28:9–15 is the maftir Torah reading for Shabbat Rosh Chodesh. Numbers 28:16–25 is the maftir Torah reading for the first two days of Passover. Numbers 28:19–25 is the maftir Torah reading for the intermediate days (חול המועד, Chol HaMoed) and seventh and eighth days of Passover. Numbers 28:26–31 is the maftir Torah reading for each day of Shavuot. Numbers 29:1–6 is the maftir Torah reading for each day of Rosh Hashanah. Numbers 29:7–11 is the maftir Torah reading for the Yom Kippur morning (שַחֲרִת, Shacharit) service. Numbers 29:12–16 is the maftir Torah reading for the first two days of Sukkot. Numbers 29:17–25 is the Torah reading for the first intermediate day of Sukkot. Numbers 29:20–28 is the Torah reading for the second intermediate day of Sukkot. Numbers 29:23–31 is the Torah reading for the third intermediate day of Sukkot. Numbers 29:26–34 is the Torah reading for the fourth intermediate day of Sukkot, as well as for Hoshana Rabbah. And Numbers 29:35–30:1 is the maftir Torah reading for both Shemini Atzeret and Simchat Torah.

Readings

In traditional Sabbath Torah reading, the parashah is divided into seven readings, or עליות, aliyot.[3]

First reading — Numbers 25:10–26:4

In the first reading (עליה, aliyah), God announced that because Phinehas had displayed his passion for God, God granted Phinehas God's pact of friendship and priesthood for all time.[4] God then told Moses to attack the Midianites to repay them for their trickery luring Israelite men to worship Baal-Peor.[5]

| Tribe | Numbers 1 | Numbers 26 | Change | % Change |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Manasseh | 32,200 | 52,700 | +20,500 | +63.7 |

| Benjamin | 35,400 | 45,600 | +10,200 | +28.8 |

| Asher | 41,500 | 53,400 | +11,900 | +28.7 |

| Issachar | 54,400 | 64,300 | +9,900 | +18.2 |

| Zebulun | 57,400 | 60,500 | +3,100 | +5.4 |

| Dan | 62,700 | 64,400 | +1,700 | +2.7 |

| Judah | 74,600 | 76,500 | +1,900 | +2.5 |

| Reuben | 46,500 | 43,730 | -2,770 | -6.0 |

| Gad | 45,650 | 40,500 | -5,150 | -11.3 |

| Naphtali | 53,400 | 45,400 | -8,000 | -15.0 |

| Ephraim | 40,500 | 32,500 | -8,000 | -19.8 |

| Simeon | 59,300 | 22,200 | -37,100 | -62.6 |

| Totals | 603,550 | 601,730 | -1,820 | -0.3 |

God instructed Moses and Eleazar to take a census of Israelite men 20 years old and up.[6]

Second reading — Numbers 26:5–51

In the second reading (עליה, aliyah), the census showed the following populations by tribe:[7]

- Reuben: 43,730

- Simeon: 22,200

- Gad: 40,500

- Judah: 76,500

- Issachar: 64,300

- Zebulun: 60,500

- Manasseh: 52,700

- Ephraim: 32,500

- Benjamin: 45,600

- Dan: 64,400

- Asher: 53,400

- Naphtali: 45,400

The total (excluding the tribe of Levi) was 601,730[8] (slightly lower than the total in the first census,[9] but with significant differences among the tribes).

The text notes in passing that when Korah's band agitated against God, the earth swallowed up Dathan and Abiram with Korah, but Korah's sons did not die.[10]

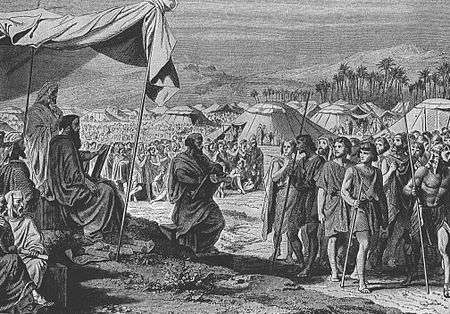

Third reading — Numbers 26:52–27:5

In the third reading (עליה, aliyah), God told Moses to apportion shares of the land according to population among those counted, and by lot.[11] The Levite men aged a month old and up amounted to 23,000, and they were not included in the regular enrollment of Israelites, as they were not to have land assigned to them.[12] Among the persons whom Moses and Eleazar enrolled was not one of those enrolled in the first census at the wilderness of Sinai, except Caleb and Joshua.[13] The daughters of Zelophehad approached Moses, Eleazar, the chieftains, and the assembly at the entrance of the Tabernacle, saying that their father left no sons, and asking that they be given a land holding.[14] Moses brought their case before God.[15]

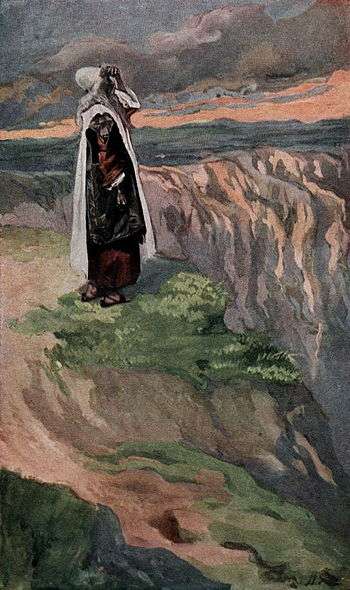

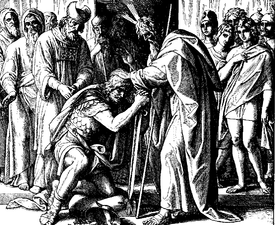

Fourth reading — Numbers 27:6–23

In the fourth reading (עליה, aliyah), God told Moses that the daughters' plea was just and instructed Moses to transfer their father's share of land to them.[16] God further instructed that if a man died without leaving a son, the Israelites were to transfer his property to his daughter, or failing a daughter to his brothers, or failing a brother to his father's brothers, or failing brothers of his father, to the nearest relative.[17] God told Moses to climb the heights of Abarim and view the Land of Israel, saying that when he had seen it, he would die, because he disobeyed God's command to uphold God's sanctity in the people's sight when he brought water from the rock in the wilderness of Zin.[18] Moses asked God to appoint someone over the community, so that the Israelites would not be like sheep without a shepherd.[19] God told Moses to single out Joshua, lay his hand on him, and commission him before Eleazar and the whole community.[20] Joshua was to present himself to Eleazar the priest, who was to seek the decision of the Urim and Thummim on whether to go out or come in.[21]

Fifth reading — Numbers 28:1–15

In the fifth reading (עליה, aliyah), God told Moses to command the Israelites to be punctilious in presenting the offerings due God at stated times.[22] The text then details the offerings for the Sabbath and Rosh Chodesh.[23]

Sixth reading — Numbers 28:16–29:11

The sixth reading (עליה, aliyah) details the offerings for Passover, Shavuot, Rosh Hashanah, and Yom Kippur.[24]

Seventh reading — Numbers 29:12–30:1

The seventh reading (עליה, aliyah) details the offerings for Sukkot and Shmini Atzeret.[25] At the end of the reading, Moses concluded his teachings to the whole community about the offerings.[26][27]

Readings according to the triennial cycle

Jews who read the Torah according to the triennial cycle of Torah reading read the parashah according to the following schedule:[28]

| Year 1 | Year 2 | Year 3 | |

|---|---|---|---|

| 2013–2014, 2016–2017, 2019–2020 . . . | 2014–2015, 2017–2018, 2020–2021 . . . | 2015–2016, 2018–2019, 2021–2022 . . . | |

| Reading | 25:10–26:51 | 26:52–28:15 | 28:16–30:1 |

| 1 | 25:10–12 | 26:52–56 | 28:16–25 |

| 2 | 25:13–15 | 26:57–62 | 28:26–31 |

| 3 | 25:16–26:4 | 26:63–27:5 | 29:1–6 |

| 4 | 26:5–11 | 27:6–14 | 29:7–11 |

| 5 | 26:12–22 | 27:15–23 | 29:12–16 |

| 6 | 26:23–34 | 28:1–10 | 29:17–28 |

| 7 | 26:35–51 | 28:11–15 | 29:29–30:1 |

| Maftir | 26:48–51 | 28:11–15 | 29:35–30:1 |

In inner-Biblical interpretation

The parashah has parallels or is discussed in these Biblical sources:[29]

Numbers chapter 25

Professor Tikva Frymer-Kensky of the University of Chicago Divinity School called the Bible's six memories of the Baal-Peor incident in Numbers 25:1–13, Numbers 31:15–16, Deuteronomy 4:3–4, Joshua 22:16–18, Ezekiel 20:21–26, and Psalm 106:28–31 a testimony to its traumatic nature and to its prominence in Israel's memory.[30]

.jpg)

In the retelling of Deuteronomy 4:3–4, God destroyed all the men who followed the Baal of Peor, but kept alive to the day of Moses's address everyone who cleaved to God. Frymer-Kensky concluded that Deuteronomy stresses the moral lesson: Very simply, the guilty perished, and those who were alive to hear Moses were innocent survivors who could avoid destruction by staying fast to God.[30]

In Joshua 22:16–18, Phinehas and ten princes of Israelite Tribes questioned the Reubenites’, Gadites’, and Manassites’ later building an altar across the Jordan, recalling that the Israelites had not cleansed themselves to that day of the iniquity of Peor, even though a plague had come upon the congregation at the time. Frymer-Kensky noted that the book of Joshua emphasizes the collective nature of sin and punishment, that the transgression of the Israelites at Peor still hung over them, and that any sin of the Reubenites, Gadites, and Manassites would bring down punishment on all Israel.[30]

In Ezekiel 20:21–26, God recalled Israel's rebellion and God's resolve to pour out God's fury on them in the wilderness. God held back then for the sake of God's Name, but swore that God would scatter them among the nations, because they looked with longing at idols. Frymer-Kensky called Ezekiel's memory the most catastrophic: Because the Israelites rebelled in the Baal-Peor incident, God vowed that they would ultimately lose the Land that they had not yet even entered. Even after the exile to Babylon, the incident loomed large in Israel's memory.[31]

Psalm 106:28–31 reports that the Israelites attached themselves to Baal Peor and ate sacrifices offered to the dead, provoking God's anger and a plague. Psalm 106:30–31 reports that Phinehas stepped forward and intervened, the plague ceased, and it was reckoned to his merit forever. Frymer-Kensky noted that the Psalm 106:28–31, like Numbers 25:1–13, includes a savior, a salvation, and an explanation of the monopoly of the priesthood by the descendants of Phineas.[31] Professor Michael Fishbane of the University of Chicago wrote that in retelling the story, the Psalmist notably omitted the explicit account of Phinehas's violent lancing of the offenders and substituted an account of the deed that could be read as nonviolent.[32]

Numbers chapter 26

In Numbers 26:2, God directed Moses and Eleazer to "take the sum of all the congregation of the children of Israel, from 20 years old and upward, . . . all that are able to go forth to war in Israel." That census yielded 43,730 men for Reuben,[33] 40,500 men for Gad,[34] and 52,700 men for Manasseh[35] — for a total of 136,930 adult men "able to go forth to war" from the three tribes. But Joshua 4:12–13 reports that "about 40,000 ready armed for war passed on in the presence of the Lord to battle" from Reuben, Gad, and the half-tribe of Manasseh — or fewer than 3 in 10 of those counted in Numbers 26. Chida explained that only the strongest participated, as Joshua asked in Joshua 1:14 for only "the mighty men of valor." Kli Yakar suggested that more than 100,000 men crossed over the Jordan to help, but when they saw the miracles at the Jordan, many concluded that God would ensure the Israelites' success and they were not needed.[36]

Numbers chapter 27

The Hebrew Bible refers to the Urim and Thummim in Exodus 28:30; Leviticus 8:8; Numbers 27:21; Deuteronomy 33:8; 1 Samuel 14:41 ("Thammim") and 28:6; Ezra 2:63; and Nehemiah 7:65; and may refer to them in references to "sacred utensils" in Numbers 31:6 and the Ephod in 1 Samuel 14:3 and 19; 23:6 and 9; and 30:7–8; and Hosea 3:4.

Numbers chapter 28

In Numbers 28:3, God commanded the Israelite people to bring to the Sanctuary, "as a regular burnt offering every day, two yearling lambs without blemish." But in Amos 4:4, the 8th century BCE prophet Amos condemned the sins of the people of Israel, saying that they, "come to Beth-el, and transgress, to Gilgal, and multiply transgression; and bring your sacrifices in the morning."

Passover

Numbers 28:16–25 refers to the Festival of Passover. In the Hebrew Bible, Passover is called:

- "Passover" (פֶּסַח, Pesach);[37]

- "The Feast of Unleavened Bread" (חַג הַמַּצּוֹת, Chag haMatzot);[38] and

- "A holy convocation" or "a solemn assembly" (מִקְרָא-קֹדֶשׁ, mikrah kodesh).[39]

Some explain the double nomenclature of "Passover" and "Feast of Unleavened Bread" as referring to two separate feasts that the Israelites combined sometime between the Exodus and when the Biblical text became settled.[40] Exodus 34:18–20 and Deuteronomy 15:19–16:8 indicate that the dedication of the firstborn also became associated with the festival.

Some believe that the "Feast of Unleavened Bread" was an agricultural festival at which the Israelites celebrated the beginning of the grain harvest. Moses may have had this festival in mind when in Exodus 5:1 and 10:9 he petitioned Pharaoh to let the Israelites go to celebrate a feast in the wilderness.[41]

"Passover," on the other hand, was associated with a thanksgiving sacrifice of a lamb, also called "the Passover," "the Passover lamb," or "the Passover offering."[42]

Exodus 12:5–6, Leviticus 23:5, and Numbers 9:3 and 5, and 28:16 direct "Passover" to take place on the evening of the fourteenth of אָבִיב, Aviv (נִיסָן, Nisan in the Hebrew calendar after the Babylonian captivity). Joshua 5:10, Ezekiel 45:21, Ezra 6:19, and 2 Chronicles 35:1 confirm that practice. Exodus 12:18–19, 23:15, and 34:18, Leviticus 23:6, and Ezekiel 45:21 direct the "Feast of Unleavened Bread" to take place over seven days and Leviticus 23:6 and Ezekiel 45:21 direct that it begin on the fifteenth of the month. Some believe that the propinquity of the dates of the two Festivals led to their confusion and merger.[41]

Exodus 12:23 and 27 link the word "Passover" (פֶּסַח, Pesach) to God's act to "pass over" (פָסַח, pasach) the Israelites' houses in the plague of the firstborn. In the Torah, the consolidated Passover and Feast of Unleavened Bread thus commemorate the Israelites' liberation from Egypt.[43]

The Hebrew Bible frequently notes the Israelites' observance of Passover at turning points in their history. Numbers 9:1–5 reports God's direction to the Israelites to observe Passover in the wilderness of Sinai on the anniversary of their liberation from Egypt. Joshua 5:10–11 reports that upon entering the Promised Land, the Israelites kept the Passover on the plains of Jericho and ate unleavened cakes and parched corn, produce of the land, the next day. 2 Kings 23:21–23 reports that King Josiah commanded the Israelites to keep the Passover in Jerusalem as part of Josiah's reforms, but also notes that the Israelites had not kept such a Passover from the days of the Biblical judges nor in all the days of the kings of Israel or the kings of Judah, calling into question the observance of even Kings David and Solomon. The more reverent 2 Chronicles 8:12–13, however, reports that Solomon offered sacrifices on the Festivals, including the Feast of Unleavened Bread. And 2 Chronicles 30:1–27 reports King Hezekiah's observance of a second Passover anew, as sufficient numbers of neither the priests nor the people were prepared to do so before then. And Ezra 6:19–22 reports that the Israelites returned from the Babylonian captivity observed Passover, ate the Passover lamb, and kept the Feast of Unleavened Bread seven days with joy.

Shavuot

Numbers 28:26–31 refers to the Festival of Shavuot. In the Hebrew Bible, Shavuot is called:

- The Feast of Weeks (חַג שָׁבֻעֹת, Chag Shavuot);[44]

- The Day of the First-fruits; (יוֹם הַבִּכּוּרִים, Yom haBikurim)[45]

- The Feast of Harvest (חַג הַקָּצִיר, Chag haKatzir);[46] and

- A holy convocation (מִקְרָא-קֹדֶשׁ, mikrah kodesh).[47]

Exodus 34:22 associates Shavuot with the first-fruits (בִּכּוּרֵי, bikurei) of the wheat harvest.[48] In turn, Deuteronomy 26:1–11 set out the ceremony for the bringing of the first fruits.

To arrive at the correct date, Leviticus 23:15 instructs counting seven weeks from the day after the day of rest of Passover, the day that they brought the sheaf of barley for waving. Similarly, Deuteronomy 16:9 directs counting seven weeks from when they first put the sickle to the standing barley.

Leviticus 23:16–19 sets out a course of offerings for the fiftieth day, including a meal-offering of two loaves made from fine flour from the first-fruits of the harvest; burnt-offerings of seven lambs, one bull, and two rams; a sin-offering of a goat; and a peace-offering of two lambs. Similarly, Numbers 28:26–30 sets out a course of offerings including a meal-offering; burnt-offerings of two bulls, one ram, and seven lambs; and one goat to make atonement. Deuteronomy 16:10 directs a freewill-offering in relation to God's blessing.

Leviticus 23:21 and Numbers 28:26 ordain a holy convocation in which the Israelites were not to work.

2 Chronicles 8:13 reports that Solomon offered burnt-offerings on the Feast of Weeks.

Numbers chapter 29

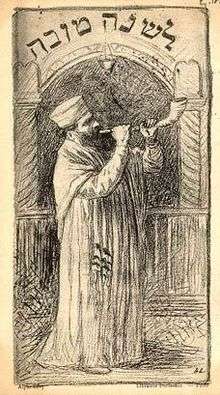

Rosh Hashanah

Numbers 29:1–6 refers to the Festival of Rosh Hashanah. In the Hebrew Bible, Rosh Hashanah is called:

- a memorial proclaimed with the blast of horns (זִכְרוֹן תְּרוּעָה, Zichron Teruah);[49]

- a day of blowing the horn (יוֹם תְּרוּעָה, Yom Teruah);[50] and

- a holy convocation (מִקְרָא-קֹדֶשׁ, mikrah kodesh).[51]

Although Exodus 12:2 instructs that the spring month of אָבִיב, Aviv (since the Babylonian captivity called נִיסָן, Nisan) "shall be the first month of the year," Exodus 23:16 and 34:22 also reflect an "end of the year" or a "turn of the year" in the autumn harvest month of תִּשְׁרֵי, Tishrei.

Levitcus 23:23–25 and Numbers 29:1–6 both describe Rosh Hashanah as an holy convocation, a day of solemn rest in which no servile work is to be done, involving the blowing of horns and an offering to God.

Ezekiel 40:1 speaks of "in the beginning of the year" (בְּרֹאשׁ הַשָּׁנָה, b'Rosh HaShanah) in תִּשְׁרֵי, Tishrei, although the Rabbis traditional interpreted Ezekiel to refer to Yom Kippur.

Ezra 3:1–3 reports that in the Persian era, when the seventh month came, the Israelites gathered together in Jerusalem, and the priests offered burnt-offerings to God, morning and evening, as written in the Law of Moses.

Nehemiah 8:1–4 reports that it was on Rosh Hashanah (the first day of the seventh month) that all the Israelites gathered together before the water gate and Ezra the scribe read the Law from early morning until midday. And Nehemiah, Ezra, and the Levites told the people that the day was holy to the Lord their God; they should neither mourn nor weep; but they should go their way, eat the fat, drink the sweet, and send portions to those who had nothing.[52]

Psalm 81:4–5 likely refers to Rosh Hashanah when it enjoins, "Blow the horn at the new moon, at the full moon of our feast day. For it is a statute for Israel, an ordinance of the God of Jacob."

Yom Kippur

Numbers 29:7–11 refers to the Festival of Yom Kippur. In the Hebrew Bible, Yom Kippur is called:

- the Day of Atonement (יוֹם הַכִּפֻּרִים, Yom HaKippurim)[53] or a Day of Atonement (יוֹם כִּפֻּרִים, Yom Kippurim);[54]

- a Sabbath of solemn rest (שַׁבַּת שַׁבָּתוֹן, Shabbat Shabbaton);[55] and

- a holy convocation (מִקְרָא-קֹדֶשׁ, mikrah kodesh).[56]

Much as Yom Kippur, on the 10th of the month of תִּשְׁרֵי, Tishrei, precedes the Festival of Sukkot, on the 15th of the month of תִּשְׁרֵי, Tishrei, Exodus 12:3–6 speaks of a period starting on the 10th of the month of נִיסָן, Nisan preparatory to the Festival of Passover, on the 15th of the month of נִיסָן, Nisan.

Levitcus 16:29–34 and 23:26–32 and Numbers 29:7–11 present similar injunctions to observe Yom Kippur. Levitcus 16:29 and 23:27 and Numbers 29:7 set the Holy Day on the tenth day of the seventh month (תִּשְׁרֵי, Tishrei). Levitcus 16:29 and 23:27 and Numbers 29:7 instruct that "you shall afflict your souls." Levitcus 23:32 makes clear that a full day is intended: "you shall afflict your souls; in the ninth day of the month at evening, from evening to evening." And Levitcus 23:29 threatens that whoever "shall not be afflicted in that same day, he shall be cut off from his people." Levitcus 16:29 and Levitcus 23:28 and Numbers 29:7 command that you "shall do no manner of work." Similarly, Levitcus 16:31 and 23:32 call it a "Sabbath of solemn rest." And in 23:30, God threatens that whoever "does any manner of work in that same day, that soul will I destroy from among his people." Levitcus 16:30, 16:32–34, and 23:27–28, and Numbers 29:11 describe the purpose of the day to make atonement for the people. Similarly, Levitcus 16:30 speaks of the purpose "to cleanse you from all your sins," and Levitcus 16:33 speaks of making atonement for the most holy place, the tent of meeting, the altar; and the priests. Levitcus 16:29 instructs that the commandment applies both to "the home-born" and to "the stranger who sojourns among you." Levitcus 16:3–25 and 23:27 and Numbers 29:8–11 command offerings to God. And Levitcus 16:31 and 23:31 institute the observance as "a statute forever."

Levitcus 16:3–28 sets out detailed procedures for the priest's atonement ritual during the time of the Temple.

Levitcus 25:8–10 instructs that after seven Sabbatical years, on the Jubilee year, on the day of atonement, the Israelites were to proclaim liberty throughout the land with the blast of the horn and return every man to his possession and to his family.

In Isaiah 57:14–58:14, the Haftarah for Yom Kippur morning, God describes "the fast that I have chosen [on] the day for a man to afflict his soul." Isaiah 58:3–5 make clear that "to afflict the soul" was understood as fasting. But Isaiah 58:6–10 goes on to impress that "to afflict the soul," God also seeks acts of social justice: "to loose the fetters of wickedness, to undo the bands of the yoke," "to let the oppressed go free," "to give your bread to the hungry, and . . . bring the poor that are cast out to your house," and "when you see the naked, that you cover him."

Sukkot

And Numbers 29:12–38 refers to the Festival of Sukkot. In the Hebrew Bible, Sukkot is called:

- "The Feast of Tabernacles (or Booths)";[57]

- "The Feast of Ingathering";[58]

- "The Feast" or "the festival";[59]

- "The Feast of the Lord";[60]

- "The festival of the seventh month";[61] and

- "A holy convocation" or "a sacred occasion."[62]

Sukkot's agricultural origin is evident from the name "The Feast of Ingathering," from the ceremonies accompanying it, and from the season and occasion of its celebration: "At the end of the year when you gather in your labors out of the field";[46] "after you have gathered in from your threshing-floor and from your winepress."[63] It was a thanksgiving for the fruit harvest.[64] And in what may explain the festival's name, Isaiah reports that grape harvesters kept booths in their vineyards.[65] Coming as it did at the completion of the harvest, Sukkot was regarded as a general thanksgiving for the bounty of nature in the year that had passed.

Sukkot became one of the most important feasts in Judaism, as indicated by its designation as "the Feast of the Lord"[66] or simply "the Feast."[59] Perhaps because of its wide attendance, Sukkot became the appropriate time for important state ceremonies. Moses instructed the children of Israel to gather for a reading of the Law during Sukkot every seventh year.[67] King Solomon dedicated the Temple in Jerusalem on Sukkot.[68] And Sukkot was the first sacred occasion observed after the resumption of sacrifices in Jerusalem after the Babylonian captivity.[69]

In the time of Nehemiah, after the Babylonian captivity, the Israelites celebrated Sukkot by making and dwelling in booths, a practice of which Nehemiah reports: "the Israelites had not done so from the days of Joshua."[70] In a practice related to that of the Four Species, Nehemiah also reports that the Israelites found in the Law the commandment that they "go out to the mountains and bring leafy branches of olive trees, pine trees, myrtles, palms and [other] leafy trees to make booths."[71] In Leviticus 23:40, God told Moses to command the people: "On the first day you shall take the product of hadar trees, branches of palm trees, boughs of leafy trees, and willows of the brook," and "You shall live in booths seven days; all citizens in Israel shall live in booths, in order that future generations may know that I made the Israelite people live in booths when I brought them out of the land of Egypt."[72] The book of Numbers, however, indicates that while in the wilderness, the Israelites dwelt in tents.[73] Some secular scholars consider Leviticus 23:39–43 (the commandments regarding booths and the four species) to be an insertion by a late redactor.[74]

Jeroboam son of Nebat, King of the northern Kingdom of Israel, whom 1 Kings 13:33 describes as practicing "his evil way," celebrated a festival on the fifteenth day of the eighth month, one month after Sukkot, "in imitation of the festival in Judah."[75] "While Jeroboam was standing on the altar to present the offering, the man of God, at the command of the Lord, cried out against the altar" in disapproval.[76]

According to the prophet Zechariah, in the messianic era, Sukkot will become a universal festival, and all nations will make pilgrimages annually to Jerusalem to celebrate the feast there.[77]

In classical rabbinic interpretation

The parashah is discussed in these rabbinic sources from the era of the Mishnah and the Talmud:[78]

Numbers chapter 25

Rabbi Johanan taught that Phinehas was able to accomplish his act of zealotry only because God performed six miracles: First, upon hearing Phinehas's warning, Zimri should have withdrawn from Cozbi and ended his transgression, but he did not. Second, Zimri should have cried out for help from his fellow Simeonites, but he did not. Third, Phinheas was able to drive his spear exactly through the sexual organs of Zimri and Cozbi as they were engaged in the act. Fourth, Zimri and Cozbi did not slip off the spear, but remained fixed so that others could witness their transgression. Fifth, an angel came and lifted up the lintel so that Phinehas could exit holding the spear. And sixth, an angel came and sowed destruction among the people, distracting the Simeonites from killing Phinheas.[79]

Rabbah bar bar Hana said in Rabbi Johanan's name that had Zimri withdrawn from his mistress and Phinehas still killed him, Phinehas would have been liable to execution for murder, and had Zimri killed Phinehas in self-defense, he would not have been liable to execution for murder, as Phinehas was a pursuer seeking to take Zimri's life.[80]

But based on Numbers 25:8 and 11, the Mishnah listed the case of a man who had sexual relations with an Aramean woman as one of three cases for which it was permissible for zealots to punish the offender on the spot.[81]

Reading the words of Numbers 25:7, "When Phinehas the son of Eleazar, son of Aaron the priest, saw," the Jerusalem Talmud asked what he saw. The Jerusalem Talmud answered that he saw the incident and remembered the law that zealots may beat up one who has sexual relations with an Aramean woman. But the Jerusalem Talmud reported that it was taught that this was not with the approval of sages. Rabbi Judah bar Pazzi taught that the sages wanted to excommunicate Phinehas, but the Holy Spirit rested upon him and stated the words of Numbers 25:13, "And it shall be to him, and to his descendants after him, the covenant of a perpetual priesthood, because he was jealous for his God, and made atonement for the people of Israel."[82]

The Gemara told that after Phinehas killed Zimri and Cozbi, the Israelites began berating Phinehas for his presumption, as he himself was descended from a Midianite idolater, Jethro. The Israelites said: "See this son of Puti (Putiel, or Jethro) whose maternal grandfather fattened (pittem) cattle for idols, and who has now slain the prince of a tribe of Israel (Zimri)!" To counter this attack, the Gemara explained, God detailed Phinehas's descent from the peaceful Aaron the Priest in Numbers 25:11. And then in Numbers 25:12, God told Moses to be the first to extend a greeting of peace to Phinehas, so as to calm the crowd. And the Gemara explained Numbers 25:13 to indicate that the atonement that Phinehas had made was worthy to atone permanently.[83]

| Aaron | Putiel (Jethro) | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Eleazar | daughter of Putiel | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Phinehas | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Similarly, the Gemara asked whether the words in Exodus 6:25, "And Eleazar Aaron's son took him one of the daughters of Putiel to wife" did not convey that Eleazar's son Phinehas descended from Jethro, who fattened (piteim) calves for idol worship. The Gemara then provided an alternative explanation: Exodus 6:25 could mean that Phinehas descended from Joseph, who conquered (pitpeit) his passions (resisting Potiphar's wife, as reported in Genesis 39). But the Gemara asked, did not the tribes sneer at Phinehas and[84] question how a youth (Phinehas) whose mother's father crammed calves for idol-worship could kill the head of a tribe in Israel (Zimri, Prince of Simeon, as reported in Numbers 25). The Gemara explained that the real explanation was that Phinehas descended from both Joseph and Jethro. If Phinehas's mother's father descended from Joseph, then Phinehas's mother's mother descended from Jethro. And if Phinehas's mother's father descended from Jethro, then Phinehas's mother's mother descended from Joseph. The Gemara explained that Exodus 6:25 implies this dual explanation of "Putiel" when it says, "of the daughters of Putiel," because the plural "daughters" implies two lines of ancestry (from both Joseph and Jethro).[85]

A Midrash interpreted Numbers 25:12, in which God gives Phinehas God's "covenant of peace," to teach that Phinehas, like Elijah, continues to live to this day, applying to Phinehas the words of Malachi 2:5, "My covenant was with him of life and peace, and I gave them to him, and of fear, and he feared Me, and was afraid of My name."[86]

Reading the words of Numbers 25:13 that Phinehas "made atonement for the children of Israel," a Midrash taught that although he did not strictly offer a sacrifice to justify the expression "atonement," his shedding the blood of the wicked was as though he had offered a sacrifice.[87]

Reading Deuteronomy 2:9, "And the Lord spoke to me, ‘Distress not the Moabites, neither contend with them in battle,'" Ulla argued that it certainly could not have entered the mind of Moses to wage war without God's authorization. So we must deduce that Moses on his own reasoned that if in the case of the Midianites who came only to assist the Moabites (in Numbers 22:4), God commanded (in Numbers 25:17), "Vex the Midianites and smite them," in the case of the Moabites themselves, the same injunction should apply even more strongly. But God told Moses that the idea that Moses had in his mind was not the idea that God had in God's mind. For God was to bring two doves forth from the Moabites and the Ammonites — Ruth the Moabitess and Naamah the Ammonitess.[88]

Numbers chapter 26

A Midrash taught that the Israelites were counted on ten occasions:[89] (1) when they went down to Egypt,[90] (2) when they went up out of Egypt,[91] (3) at the first census in Numbers,[92] (4) at the second census in Numbers,[93] (5) once for the banners, (6) once in the time of Joshua for the division of the land of Israel, (7) once by Saul,[94] (8) a second time by Saul,[95] (9) once by David,[96] and (10) once in the time of Ezra.[97]

Noting that Numbers 26:1 speaks of "after the plague" immediately before reporting that God ordered the census, a Midrash concluded that whenever the Israelites were struck, they needed to be counted, as a shepherd will count the sheep after a wolf attacks. Alternatively, the Midrash taught that God ordered Moses to count the Israelites as Moses neared death, much as a shepherd entrusted with a set number of sheep must count those that remain when the shepherd returns the sheep to their owner.[98]

The Rabbis taught in a Baraita that upon entering a barn to measure the new grain one should recite the blessing, "May it be Your will O Lord, our God, that You may send blessing upon the work of our hands." Once one has begun to measure, one should say, "Blessed be the One who sends blessing into this heap." If, however, one first measured the grain and then recited the blessing, then prayer is in vain, because blessing is not to be found in anything that has been already weighed or measured or numbered, but only in a thing hidden from sight.[99]

Rabbi Isaac taught that it is forbidden to count Israel even for the purpose of fulfilling a commandment, as 1 Samuel 11:8 can be read, "And he numbered them with pebbles (בְּבֶזֶק, be-bezek)." Rav Ashi demurred, asking how Rabbi Isaac knew that the word בֶזֶק, bezek, in 1 Samuel 11:8 means being broken pieces (that is, pebbles). Rav Ashi suggested that perhaps בֶזֶק, Bezek, is the name of a place, as in Judges 1:5, which says, "And they found Adoni-Bezek in Bezek (בְּבֶזֶק, be-bezek)." Rav Ashi argued that the prohibition of counting comes from 1 Samuel 15:4, which can be read, "And Saul summoned the people and numbered them with sheep (טְּלָאִים, telaim)." Rabbi Eleazar taught that whoever counts Israel transgresses a Biblical prohibition, as Hosea 2:1 says, "Yet the number of the children of Israel shall be as the sand of the sea, which cannot be measured." Rav Nahman bar Isaac said that such a person would transgress two prohibitions, for Hosea 2:1 says, "Which cannot be measured nor numbered." Rabbi Samuel bar Nahmani reported that Rabbi Jonathan noted a potential contradiction, as Hosea 2:1 says, "Yet the number of the children of Israel shall be as the sand of the sea" (implying a finite number, but Hosea 2:1 also says, "Which cannot be numbered" (implying that they will not have a finite number). The Gemara answered that there is no contradiction, for the latter part of Hosea 2:1 speaks of the time when Israel fulfils God's will, while the earlier part of Hosea 2:1 speaks of the time when they do not fulfill God's will. Rabbi said on behalf of Abba Jose ben Dosthai that there is no contradiction, for the latter part of Hosea 2:1 speaks of counting done by human beings, while the earlier part of Hosea 2:1 speaks of counting by Heaven.[100]

Rava found support in Numbers 26:8 for the proposition that sometimes texts refer to "sons" when they mean a single son.[101]

A Tanna in the name of Rabbi deduced from the words "the sons of Korah did not die" in Numbers 26:11 that Providence set up a special place for them to stand on high in Gehinnom.[102] There, Korah's sons sat and sang praises to God. Rabbah bar bar Hana told that once when he was travelling, an Arab showed him where the earth swallowed Korah's congregation. Rabbah bar bar Hana saw two cracks in the ground from which smoke issued. He took a piece of wool, soaked it in water, attached it to the point of his spear, and passed it over the cracks, and the wool was singed. The Arab told Rabbah bar bar Hana to listen, and he heard them saying, "Moses and his Torah are true, but Korah's company are liars." The Arab told Rabbah bar bar Hana that every 30 days Gehinnom caused them to return for judgment, as if they were being stirred like meat in a pot, and every 30 days they said those same words.[103]

A Midrash explained why the sons of Korah were saved. When they were sitting with their father, and they saw Moses, they hung their heads and lamented that if they stood up for Moses, they would be showing disrespect for their father, but if they did not rise, they would be disregarding Leviticus 19:32, "You shall rise up before the hoary head." They concluded that they had better rise for their teacher Moses, even though they would thereby be showing disrespect for our father. At that moment, thoughts of repentance stirred in their hearts.[104]

A Midrash taught that at the moment when the earth opened up, Korah's sons were suspended in the air.[105] When the sons of Korah saw the gaping abyss below on one side and the fire of Gehinnom on the other, they were unable to open their mouths to confess. But as soon as thoughts of repentance stirred in their hearts, God accepted them. Whatever thoughts one of the sons developed, the others developed as well, so that all three were of one heart.[106] The area around them split apart, but the spot on which each stood was not touched. They stood separately like three pillars.[107] Moses, Aaron, and all the great scholars came to hear the song of the sons of Korah, and from this they learned to sing songs before God.[108]

The Pirke De-Rabbi Eliezer taught that the prophet Jonah saved the fish that swallowed Jonah from being devoured by Leviathan, and in exchange, the fish showed Jonah the sea and the depths. The fish showed Jonah the great river of the waters of the Ocean, the paths of the Reed Sea through which Israel passed in the Exodus, the place from where the waves of the sea and its billows flow, the pillars of the earth in its foundations, the lowest Sheol, Gehinnom, and what was beneath the Temple in Jerusalem. Beneath the Temple, Jonah saw the Foundation Stone fixed in the depths, and the sons of Korah were standing and praying over it. The sons of Korah told Jonah that he stood beneath the Temple of God, and if he prayed, he would be answered. Forthwith, Jonah prayed to God to restore Jonah to life. In response, God hinted to the fish, and the fish vomited out Jonah onto the dry land, as reported in Jonah 2:10.[109]

A Baraita taught that the Serah the daughter of Asher mentioned in both Genesis 46:17 and Numbers 26:46 survived from the time Israel went down to Egypt to the time of the wandering in the Wilderness. The Gemara taught that Moses went to her to ask where the Egyptians had buried Joseph. She told him that the Egyptians had made a metal coffin for Joseph. The Egyptians set the coffin in the Nile so that its waters would be blessed. Moses went to the bank of the Nile and called to Joseph that the time had arrived for God to deliver the Israelites, and the oath that Joseph had imposed upon the children of Israel in Genesis 50:25 had reached its time of fulfillment. Moses called on Joseph to show himself, and Joseph's coffin immediately rose to the surface of the water.[110]

Similarly, a Midrash taught that Serah (mentioned in Numbers 26:46) conveyed to the Israelites a secret password handed down from Jacob so that they would recognize their deliverer. The Midrash told that when (as Exodus 4:30 reports) "Aaron spoke all the words" to the Israelite people, "And the people believed" (as Exodus 4:31 reports), they did not believe only because they had seen the signs. Rather, (as Exodus 4:31 reports), "They heard that the Lord had visited" — they believed because they heard, not because they saw the signs. What made them believe was the sign of God's visitation that God communicated to them through a tradition from Jacob, which Jacob handed down to Joseph, Joseph to his brothers, and Asher, the son of Jacob, handed down to his daughter Serah, who was still alive at the time of Moses and Aaron. Asher told Serah that any redeemer who would come and say the password to the Israelites would be their true deliverer. So when Moses came and said the password, the people believed him at once.[111]

Interpreting Numbers 26:53 and 26:55, the Gemara noted a dispute over whether the land of Israel was apportioned according to those who came out of Egypt or according to those who went into the land of Israel. It was taught in a Baraita that Rabbi Josiah said that the land of Israel was apportioned according to those who came out of Egypt, as Numbers 26:55 says, "according to the names of the tribes of their fathers they shall inherit." The Gemara asked what then to make of Numbers 26:53, which says, "Unto these the land shall be divided for an inheritance." The Gemara proposed that "unto these" meant adults, to the exclusion of minors. But Rabbi Jonathan taught that the land was apportioned according to those who entered the land, for Numbers 26:53 says, "Unto these the land shall be divided for an inheritance." The Gemara posited that according to this view, Numbers 26:55 taught that the manner of inheritance of the land of Israel differed from all other modes of inheritance in the world. For in all other modes of inheritance in the world, the living inherit from the dead, but in this case, the dead inherited from the living. Rabbi Simeon ben Eleazar taught a third view — that the land was divided both according to those who left Egypt and also according to those who entered the land of Israel, so as to carry out both verses. The Gemara explained that according to this view, one among those who came out of Egypt received a share among those who came out of Egypt, and one who entered the land of Israel received a share among those who entered the land. And one who belonged to both categories received a share among both categories.[112]

.jpg)

Abba Halifa of Keruya asked Rabbi Hiyya bar Abba why Genesis 46:27 reported that 70 people from Jacob's household came to Egypt, while Genesis 46:8–27 enumerated only 69 individuals. Rabbi Hiyya reported that Rabbi Hama bar Hanina taught that the seventieth person was the mother of Moses, Jochebed, who was conceived on the way from Canaan to Egypt and born as Jacob's family passed between the city walls as they entered Egypt, for Numbers 26:59 reported that Jochebed "was born to Levi in Egypt," implying that her conception was not in Egypt.[113]

The Gemara taught that the use of the pronoun "he" (הוּא, hu) in an introduction, as in the words "These are (הוּא, hu) that Dathan and Abiram" in Numbers 26:9, signifies that they were the same in their wickedness from the beginning to the end. Similar uses appear in Genesis 36:43 to teach Esau's enduring wickedness, in 2 Chronicles 28:22 to teach Ahaz's enduring wickedness, in Esther 1:1 to teach Ahasuerus's enduring wickedness, in 1 Chronicles 1:27 to teach Abraham's enduring righteousness, in Exodus 6:26 to teach Moses and Aaron's enduring righteousness, and in 1 Samuel 17:14 to teach David's enduring humility.[114]

The Gemara asked why the Tannaim felt that the allocation of the Land of Israel "according to the names of the tribes of their fathers" in Numbers 26:55 meant that the allocation was with reference to those who left Egypt; perhaps, the Gemara supposed, it might have meant the 12 tribes and that the Land was to be divided into 12 equal portions? The Gemara noted that in Exodus 6:8, God told Moses to tell the Israelites who were about to leave Egypt, "And I will give it you for a heritage; I am the Lord," and that meant that the Land was the inheritance from the fathers of those who left Egypt.[115]

A Midrash noted that Scripture records the death of Nadab and Abihu in numerous places (Leviticus 10:2 and 16:1; Numbers 3:4 and 26:61; and 1 Chronicles 24:2). This teaches that God grieved for Nadab and Abihu, for they were dear to God. And thus Leviticus 10:3 quotes God to say: "Through them who are near to Me I will be sanctified."[116]

Numbers chapter 27

A Midrash explained why the report of Numbers 27:1–11 about the daughters of Zelophehad follows immediately after the report of Numbers 26:65 about the death of the wilderness generation. The Midrash noted that Numbers 26:65 says, "there was not left a man of them, save Caleb the son of Jephunneh," because the men had been unwilling to enter the Land. But the Midrash taught that Numbers 27:1 says, "then drew near the daughters of Zelophehad," to show that the women still sought an inheritance in the Land. The Midrash noted that in the incident of the Golden Calf, in Exodus 32:2, Aaron told them: "Break off the golden rings that are in the ears of your wives," but the women refused to participate, as Exodus 32:3 indicates when it says, "And all the people broke off the golden rings that were in their ears." Similarly, the Midrash noted that Numbers 14:36 says that in the incident of the spies, "the men . . . when they returned, made all the congregation to murmur against him." The Midrash taught that in that generation, the women built up fences that the men broke down.[117]

Noting that Numbers 27:1 reported the generations from Joseph to the daughters of Zelophehad, the Sifre taught that the daughters of Zelophehad loved the Land of Israel just as much as their ancestor Joseph did (when in Genesis 50:25 he extracted an oath from his brothers to return his body to the Land of Israel for burial).[118]

Chapter 8 of tractate Bava Batra in the Mishnah and Babylonian Talmud and chapter 7 of tractate Bava Batra in the Tosefta interpreted the laws of inheritance in Numbers 27:1–11 and 36:1–9.[119]

Rabbi Joshua taught that Zelophehad's daughters' in Numbers 27:2–4 petitioned first the assembly, then the chieftains, then Eleazar, and finally Moses, but Abba Hanan said in the name of Rabbi Eliezer taught that Zelophehad's daughters stood before all of them as they were sitting together.[120]

Noting that the words "in the wilderness" appeared both in Numbers 27:3 (where Zelophehad's daughters noted that their father Zelophehad had not taken part in Korah's rebellion) and in Numbers 15:32 (which tells the story of the Sabbath violator), Rabbi Akiva taught in a Baraita that Zelophehad was the man executed for gathering sticks on the Sabbath. Rabbi Judah ben Bathyra answered Akiva that Akiva would have to give an account for his accusation. For either Akiva was right that Zelophehad was the man executed for gathering sticks on the Sabbath, and Akiva revealed something that the Torah shielded from public view, or Akiva was wrong that Zelophehad was the man executed for gathering sticks on the Sabbath, and Akiva cast a stigma upon a righteous man. But the Gemara answered that Akiva learned a tradition from the Oral Torah (that went back to Sinai, and thus the Torah did not shield the matter from public view). The Gemara then asked, according to Rabbi Judah ben Bathyra, of what sin did Zelophehad die (as his daughters reported in Numbers 27:3 that "he died in his own sin")? The Gemara reported that according to Rabbi Judah ben Bathyra, Zelophehad was among those who "presumed to go up to the top of the mountain" in Numbers 14:44 (to try and fail to take the Land of Israel after the incident of the spies).[121]

Rabbi Hidka recounted that Simeon of Shikmona, a fellow disciple of Rabbi Akiva, taught that Moses knew that the daughters of Zelophehad were entitled to inherit, but he did not know whether they were to take the double portion of the firstborn or not (and thus, as Numbers 27:5 reports, took the case to God). Moses would have in any case written the laws of inheritance in Numbers 27:1–11 and 36:1–9, but as the daughters of Zelophehad were meritorious, the Torah tells the laws of inheritance through their story.[122]

Rabbi Hanina (or some say Rabbi Josiah) taught that Numbers 27:5, when Moses found himself unable to decide the case of the daughters of Zelophehad, reports the punishment of Moses for his arrogance when he told the judges in Deuteronomy 1:17: "the cause that is too hard for you, you shall bring to me, and I will hear it." Rav Nahman objected to Rabbi Hanina's interpretation, noting that Moses did not say that he would always have the answers, but merely that he would rule if he knew the answer or seek instruction if he did not. Rav Nahman cited a Baraita to explain the case of the daughters of Zelophehad: God had intended that Moses write the laws of inheritance, but found the daughters of Zelophehad worthy to have the section recorded on their account.[123]

The Mishnah taught that the daughters of Zelophehad took three shares in the inheritance of the Land of Israel: (1) the share of their father Zelophehad, who was among those who came out of Egypt; (2) their father's share among his brothers in the estate of Hepher, Zelophehad's father; and (3) an extra share in Hepher's estate, as Zelophehad was a firstborn son, who takes two shares.[124]

A Baraita taught that Zelophehad's daughters were wise, Torah students, and righteous.[125] And a Baraita taught that Zelophehad's daughters were equal in merit, and that is why the order of their names varies between Numbers 27:1 and Numbers 36:11.[126] According to the Gemara, they demonstrated their wisdom by raising their case in a timely fashion, just as Moses was expounding the law of levirate marriage, or yibbum, and they argued for their inheritance by analogy to that law.[125]

The Gemara implied that the sin of Moses in striking the rock at Meribah compared favorably to the sin of David. The Gemara reported that Moses and David were two good leaders of Israel. Moses begged God that his sin be recorded, as it is in Numbers 20:12, 20:23–24, and 27:13–14, and Deuteronomy 32:51. David, however, begged that his sin be blotted out, as Psalm 32:1 says, "Happy is he whose transgression is forgiven, whose sin is pardoned." The Gemara compared the cases of Moses and David to the cases of two women whom the court sentenced to be lashed. One had committed an indecent act, while the other had eaten unripe figs of the seventh year in violation of Leviticus 25:6. The woman who had eaten unripe figs begged the court to make known for what offense she was being flogged, lest people say that she was being punished for the same sin as the other woman. The court thus made known her sin, and the Torah repeatedly records the sin of Moses.[127]

Noting that Moses asked God to designate someone to succeed him in Numbers 27:16, soon after the incident of Zelophehad's daughters, a Midrash deduced that when the daughters of Zelophehad inherited from their father, Moses argued that it would surely be right for his sons to inherit his glory. God, however, replied (in the words of Proverbs 27:18) that "Whoever keeps the fig-tree shall eat its fruit; and whoever waits on the master shall be honored." The sons of Moses sat idly by and did not study Torah, but Joshua served Moses and showed him great honor, rose early in the morning and remained late at night at the House of Assembly, and arranged the benches and spread the mats. As he had served Moses with all his might, he was worthy to serve Israel, and thus God in Numbers 27:18 directed Moses to "take Joshua the son of Nun" as his successor.[128]

Reading Ecclesiastes 1:5, "The sun also rises, and the sun goes down," Rabbi Abba taught that since we of course know that the sun rises and sets, Ecclesiastes 1:5 means that before God causes the sun of one righteous person to set, God causes the sun of another righteous person to rise. Thus before God caused the sun of Moses to set, God caused Joshua's sun to rise, as Numbers 27:18 reports, "And the Lord said to Moses: ‘Take Joshua the son of Nun . . . and lay your hand upon him.'"[129]

In Proverbs 8:15, Wisdom (which the Rabbis equated with the Torah) says, "By me kings reign, and princes decree justice." A Midrash taught that Proverbs 8:15 thus reports what actually happened to Joshua, for as Numbers 27:18 reports, it was not the sons of Moses who succeeded their father, but Joshua. And the Midrash taught that Proverbs 27:18, "And he who waits on his master shall be honored," also alludes to Joshua, for Joshua ministered to Moses day and night, as reported by Exodus 33:11, which says, "Joshua departed not out of the Tent," and Numbers 11:28, which says, "Joshua . . . said: ‘My lord Moses, shut them in.'" Consequently, God honored Joshua by saying of Joshua in Numbers 27:21: "He shall stand before Eleazar the priest, who shall inquire for him by the judgment of the Urim." And because Joshua served his master Moses, Joshua attained the privilege of receiving the Holy Spirit, as Joshua 1:1 reports, "Now it came to pass after the death of Moses . . . that the Lord spoke to Joshua, the minister of Moses." The Midrash taught that there was no need for Joshua 1:1 to state, "the minister of Moses," so the purpose of the statement "the minister of Moses" was to explain that Joshua was awarded the privilege of prophecy because he was the minister of Moses.[130]

The Gemara taught that God's instruction to Moses in Numbers 27:20 to put some of his honor on Joshua was not to transfer all of the honor of Moses. The elders of that generation compared the countenance of Moses to that of the sun and the countenance of Joshua to that of the moon. The elders considered it a shame and a reproach that there had been such a decline in the stature of Israel's leadership in the course of just one generation.[131]

The Mishnah taught that "one inquired [of the Urim and Thummim] only for a king."[132] The Gemara asked what the Scriptural basis was for this teaching. The Gemara answered that Rabbi Abbahu read Numbers 27:21, "And he shall stand before Eleazar the priest, who shall inquire for him by the judgment of the Urim . . . ; at his word shall they go out . . . , both he, and all the children of Israel with him, even all the congregation," to teach that "he" (that is, Joshua) meant the king, "and all the children of Israel with him" (that is, Eleazar) meant the priest Anointed for Battle, and "even all the congregation" meant the Sanhedrin.[133]

Rabbi Eliezer noted that in Numbers 27:21 God directs that Joshua "shall stand before Eleazar the priest," and yet Scripture does not record that Joshua ever sought Eleazar's guidance.[134]

The Gemara taught that although the decree of a prophet could be revoked, the decree of the Urim and Thummim could not be revoked, as Numbers 27:21 says, "By the judgment of the Urim." A Baraita explained why the Urim and Thummim were called by those names: The term "Urim" is like the Hebrew word for "lights," and thus it was called "Urim" because it enlightened. The term "Thummim" is like the Hebrew word tam meaning "to be complete," and thus it was called "Thummim" because its predictions were fulfilled. The Gemara discussed how they used the Urim and Thummim: Rabbi Johanan said that the letters of the stones in the breastplate stood out to spell out the answer. Resh Lakish said that the letters joined each other to spell words. But the Gemara noted that the Hebrew letter צ, tsade, was missing from the list of the 12 tribes of Israel. Rabbi Samuel bar Isaac said that the stones of the breastplate also contained the names of Abraham, Isaac and Jacob. But the Gemara noted that the Hebrew letter ט, teth, was also missing. Rav Aha bar Jacob said that they also contained the words: "The tribes of Jeshurun."[135]

.jpg)

The Pirke De-Rabbi Eliezer taught that when Israel sinned in the matter of the devoted things, as reported in Joshua 7:11, Joshua looked at the 12 stones corresponding to the 12 tribes that were upon the High Priest's breastplate. For every tribe that had sinned, the light of its stone became dim, and Joshua saw that the light of the stone for the tribe of Judah had become dim. So Joshua knew that the tribe of Judah had transgressed in the matter of the devoted things. Similarly, the Pirke De-Rabbi Eliezer taught that Saul saw the Philistines turning against Israel, and he knew that Israel had sinned in the matter of the ban. Saul looked at the 12 stones, and for each tribe that had followed the law, its stone (on the High Priest's breastplate) shined with its light, and for each tribe that had transgressed, the light of its stone was dim. So Saul knew that the tribe of Benjamin had trespassed in the matter of the ban.[136]

The Mishnah reported that with the death of the former prophets, the Urim and Thummim ceased.[137] In this connection, the Gemara reported differing views of who the former prophets were. Rav Huna said they were David, Samuel, and Solomon. Rav Nachman said that during the days of David, they were sometimes successful and sometimes not (getting an answer from the Urim and Thummim), for Zadok consulted it and succeeded, while Abiathar consulted it and was not successful, as 2 Samuel 15:24 reports, "And Abiathar went up." (He retired from the priesthood because the Urim and Thummim gave him no reply.) Rabbah bar Samuel asked whether the report of 2 Chronicles 26:5, "And he (King Uzziah of Judah) set himself to seek God all the days of Zechariah, who had understanding in the vision of God," did not refer to the Urim and Thummim. But the Gemara answered that Uzziah did so through Zechariah's prophecy. A Baraita told that when the first Temple was destroyed, the Urim and Thummim ceased, and explained Ezra 2:63 (reporting events after the Jews returned from the Babylonian Captivity), "And the governor said to them that they should not eat of the most holy things till there stood up a priest with Urim and Thummim," as a reference to the remote future, as when one speaks of the time of the Messiah. Rav Nachman concluded that the term "former prophets" referred to a period before Haggai, Zechariah, and Malachi, who were latter prophets.[138] And the Jerusalem Talmud taught that the "former prophets" referred to Samuel and David, and thus the Urim and Thummim did not function in the period of the First Temple, either.[139]

| Festivals | Verses | Bulls | Rams | Lambs | Goats | Totals |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Sabbath | Numbers 28:9–10 | 0 | 0 | 2 | 0 | 2 |

| New Month | Numbers 28:11–15 | 2 | 1 | 7 | 1 | 11 |

| Passover (Daily) | Numbers 28:16–25 | 2 | 1 | 7 | 1 | 11 |

| Shavuot | Numbers 28:26–31 | 2 | 1 | 7 | 1 | 11 |

| Rosh Hashanah | Numbers 29:1–6 | 1 | 1 | 7 | 1 | 10 |

| Yom Kippur | Numbers 29:7–11 | 1 | 1 | 7 | 1 | 10 |

| Sukkot Day 1 | Numbers 29:12–16 | 13 | 2 | 14 | 1 | 30 |

| Sukkot Day 2 | Numbers 29:17–19 | 12 | 2 | 14 | 1 | 29 |

| Sukkot Day 3 | Numbers 29:20–22 | 11 | 2 | 14 | 1 | 28 |

| Sukkot Day 4 | Numbers 29:23–25 | 10 | 2 | 14 | 1 | 27 |

| Sukkot Day 5 | Numbers 29:26–28 | 9 | 2 | 14 | 1 | 26 |

| Sukkot Day 6 | Numbers 29:29–31 | 8 | 2 | 14 | 1 | 25 |

| Sukkot Day 7 | Numbers 29:32–34 | 7 | 2 | 14 | 1 | 24 |

| Shemini Atzeret | Numbers 29:35–38 | 1 | 1 | 7 | 1 | 10 |

| Annual Totals+ | Numbers 28:9–29:38 | 113 | 37 | 363 | 30 | 543 |

| +Assuming 52 Sabbaths, 12 New Months, and 7 days of Passover per year | ||||||

Numbers chapter 28

Tractate Tamid in the Mishnah and Babylonian Talmud interpreted the laws of the regular offerings in Numbers 28:3–10.[140]

The Gemara noted that in listing the several Festivals in Exodus 23:15, Leviticus 23:5, Numbers 28:16, and Deuteronomy 16:1, the Torah always begins with Passover.[141]

Tractate Beitzah in the Mishnah, Tosefta, Jerusalem Talmud, and Babylonian Talmud interpreted the laws common to all of the Festivals in Exodus 12:3–27, 43–49; 13:6–10; 23:16; 34:18–23; Leviticus 16; 23:4–43; Numbers 9:1–14; 28:16–30:1; and Deuteronomy 16:1–17; 31:10–13.[142]

Tractate Pesachim in the Mishnah, Tosefta, Jerusalem Talmud, and Babylonian Talmud interpreted the laws of the Passover (פֶּסַח, Pesach) in Exodus 12:3–27, 43–49; 13:6–10; 23:15; 34:25; Leviticus 23:4–8; Numbers 9:1–14; 28:16–25; and Deuteronomy 16:1–8.[143]

The Mishnah noted differences between the first Passover in Exodus 12:3–27, 43–49; 13:6–10; 23:15; 34:25; Leviticus 23:4–8; Numbers 9:1–14; 28:16–25; and Deuteronomy 16:1–8. and the second Passover in Numbers 9:9–13. The Mishnah taught that the prohibitions of Exodus 12:19 that "seven days shall there be no leaven found in your houses" and of Exodus 13:7 that "no leaven shall be seen in all your territory" applied to the first Passover; while at the second Passover, one could have both leavened and unleavened bread in one's house. And the Mishnah taught that for the first Passover, one was required to recite the Hallel (Psalms 113–118) when the Passover lamb was eaten; while the second Passover did not require the reciting of Hallel when the Passover lamb was eaten. But both the first and second Passovers required the reciting of Hallel when the Passover lambs were offered, and both Passover lambs were eaten roasted with unleavened bread and bitter herbs. And both the first and second Passovers took precedence over the Sabbath.[144]

Numbers chapter 29

Tractate Rosh Hashanah in the Mishnah, Tosefta, Jerusalem Talmud, and Babylonian Talmud interpreted the laws of Rosh Hashanah in Numbers 29:1–6 and Leviticus 23:23–25.[145]

The Mishnah taught that Divine judgment is passed on the world at four seasons (based on the world's actions in the preceding year) — at Passover for produce; at Shavuot for fruit; at Rosh Hashanah all creatures pass before God like children of maron (one by one), as Psalm 33:15 says, "He Who fashions the heart of them all, Who considers all their doings." And on Sukkot, judgment is passed in regard to rain.[146]

Rabbi Meir taught that all are judged on Rosh Hashanah and the decree is sealed on Yom Kippur. Rabbi Judah, however, taught that all are judged on Rosh Hashanah and the decree of each and every one of them is sealed in its own time — at Passover for grain, at Shavuot for fruits of the orchard, at Sukkot for water. And the decree of humankind is sealed on Yom Kippur. Rabbi Jose taught that humankind is judged every single day, as Job 7:17–18 says, "What is man, that You should magnify him, and that You should set Your heart upon him, and that You should remember him every morning, and try him every moment?"[147]

Rav Kruspedai said in the name of Rabbi Johanan that on Rosh Hashanah, three books are opened in Heaven — one for the thoroughly wicked, one for the thoroughly righteous, and one for those in between. The thoroughly righteous are immediately inscribed definitively in the book of life. The thoroughly wicked are immediately inscribed definitively in the book of death. And the fate of those in between is suspended from Rosh Hashanah to Yom Kippur. If they deserve well, then they are inscribed in the book of life; if they do not deserve well, then they are inscribed in the book of death. Rabbi Abin said that Psalm 69:29 tells us this when it says, "Let them be blotted out of the book of the living, and not be written with the righteous." "Let them be blotted out from the book" refers to the book of the wicked. "Of the living" refers to the book of the righteous. "And not be written with the righteous" refers to the book of those in between. Rav Nahman bar Isaac derived this from Exodus 32:32, where Moses told God, "if not, blot me, I pray, out of Your book that You have written." "Blot me, I pray" refers to the book of the wicked. "Out of Your book" refers to the book of the righteous. "That you have written" refers to the book of those in between. It was taught in a Baraita that the House of Shammai said that there will be three groups at the Day of Judgment — one of thoroughly righteous, one of thoroughly wicked, and one of those in between. The thoroughly righteous will immediately be inscribed definitively as entitled to everlasting life; the thoroughly wicked will immediately be inscribed definitively as doomed to Gehinnom, as Daniel 12:2 says, "And many of them who sleep in the dust of the earth shall awake, some to everlasting life and some to reproaches and everlasting abhorrence." Those in between will go down to Gehinnom and scream and rise again, as Zechariah 13:9 says, "And I will bring the third part through the fire, and will refine them as silver is refined, and will try them as gold is tried. They shall call on My name and I will answer them." Of them, Hannah said in 1 Samuel 2:6, "The Lord kills and makes alive, He brings down to the grave and brings up." The House of Hillel, however, taught that God inclines the scales towards grace (so that those in between do not have to descend to Gehinnom), and of them David said in Psalm 116:1–3, "I love that the Lord should hear my voice and my supplication . . . The cords of death compassed me, and the straits of the netherworld got hold upon me," and on their behalf David composed the conclusion of Psalm 116:6, "I was brought low and He saved me."[148]

A Baraita taught that on Rosh Hashanah, God remembered each of Sarah, Rachel, and Hannah and decreed that they would bear children. Rabbi Eliezer found support for the Baraita from the parallel use of the word "remember" in Genesis 30:22, which says about Rachel, "And God remembered Rachel," and in Leviticus 23:24, which calls Rosh Hashanah "a remembrance of the blast of the trumpet."[149]

Rabbi Joshua son of Korchah taught that Moses stayed on Mount Sinai 40 days and 40 nights, reading the Written Law by day, and studying the Oral Law by night. After those 40 days, on the 17th of Tammuz, Moses took the Tablets of the Law, descended into the camp, broke the Tablets in pieces, and killed the Israelite sinners. Moses then spent 40 days in the camp, until he had burned the Golden Calf, ground it into powder like the dust of the earth, destroyed the idol worship from among the Israelites, and put every tribe in its place. And on the New Moon (ראש חודש, Rosh Chodesh) of Elul (the month before Rosh Hashanah), God told Moses in Exodus 24:12: "Come up to Me on the mount," and let them sound the shofar throughout the camp, for, behold, Moses has ascended the mount, so that they do not go astray again after the worship of idols. God was exalted with that shofar, as Psalm 47:5 says, "God is exalted with a shout, the Lord with the sound of a trumpet." Therefore, the Sages instituted that the shofar should be sounded on the New Moon of Elul every year.[150]

Tractate Yoma in the Mishnah, Tosefta, Jerusalem Talmud, and Babylonian Talmud interpreted the laws of Yom Kippur in Leviticus 16 and 23:26–32 and Numbers 29:7–11.[151]

Tractate Sukkah in the Mishnah, Tosefta, Jerusalem Talmud, and Babylonian Talmud interpreted the laws of Sukkot in Exodus 23:16; 34:22; Leviticus 23:33–43; Numbers 29:12–34; and Deuteronomy 16:13–17; 31:10–13.[152]

The Mishnah taught that a sukkah can be no more than 20 cubits high. Rabbi Judah, however, declared taller sukkot valid. The Mishnah taught that a sukkah must be at least 10 handbreadths high, have three walls, and have more shade than sun.[153] The House of Shammai declared invalid a sukkah made 30 days or more before the festival, but the House of Hillel pronounced it valid. The Mishnah taught that if one made the sukkah for the purpose of the festival, even at the beginning of the year, it is valid.[154]

The Mishnah taught that a sukkah under a tree is as invalid as a sukkah within a house. If one sukkah is erected above another, the upper one is valid, but the lower is invalid. Rabbi Judah said that if there are no occupants in the upper one, then the lower one is valid.[155]

It invalidates a sukkah to spread a sheet over the sukkah because of the sun, or beneath it because of falling leaves, or over the frame of a four-post bed. One may spread a sheet, however, over the frame of a two-post bed.[156]

It is not valid to train a vine, gourd, or ivy to cover a sukkah and then cover it with sukkah covering (s'chach). If, however, the sukkah-covering exceeds the vine, gourd, or ivy in quantity, or if the vine, gourd, or ivy is detached, it is valid. The general rule is that one may not use for sukkah-covering anything that is susceptible to ritual impurity (טָמְאָה, tumah) or that does not grow from the soil. But one may use for sukkah-covering anything not susceptible to ritual impurity that grows from the soil.[157]

Bundles of straw, wood, or brushwood may not serve as sukkah-covering. But any of them, if they are untied, are valid. All materials are valid for the walls.[158]

Rabbi Judah taught that one may use planks for the sukkah-covering, but Rabbi Meir taught that one may not. The Mishnah taught that it is valid to place a plank four handbreadths wide over the sukkah, provided that one does not sleep under it.[159]

Rabbi Joshua maintained that rejoicing on a Festival is a religious duty. For it was taught in a Baraita: Rabbi Eliezer said: A person has nothing else to do on a Festival aside from either eating and drinking or sitting and studying. Rabbi Joshua said: Divide it: Devote half of the Festival to eating and drinking, and half to the House of Study. Rabbi Johanan said: Both deduce this from the same verse. One verse Deuteronomy 16:8 says, "a solemn assembly to the Lord your God," while Numbers 29:35 says, "there shall be a solemn assembly to you." Rabbi Eliezer held that this means either entirely to God or entirely to you. But Rabbi Joshua held: Divide it: Devote half the Festival to God and half to yourself.[160]

The Mishnah taught that a stolen or a withered palm-branch is invalid to fulfill the commandment of Leviticus 23:40. If its top is broken off or its leaves detached from the stem, it is invalid. If its leaves are merely spread apart but still joined to the stem at their roots, it is valid. Rabbi Judah taught that in that case, one should tie the leaves at the top. A palm-branch that is three handbreadths in length, long enough to wave, is valid.[161] The Gemara explained that a withered palm branch fails to meets the requirement of Leviticus 23:40 because it is not (in the term of Leviticus 23:40) "goodly." Rabbi Johanan taught in the name of Rabbi Simeon ben Yohai that a stolen palm-branch is unfit because use of it would be a precept fulfilled through a transgression, which is forbidden. Rabbi Ammi also stated that a withered palm-branch is invalid because it is not in the word of Leviticus 23:40 "goodly," and a stolen one is invalid because it constitutes a precept fulfilled through a transgression.[162]

Similarly, the Mishnah taught that a stolen or withered myrtle is not valid. If its tip is broken off, or its leaves are severed, or its berries are more numerous than its leaves, it is invalid. But if one picks off berries to diminish their number, it is valid. One may not, however, pick them on the Festival.[163]

Similarly, the Mishnah taught that a stolen or withered willow-branch is invalid. One whose tip is broken off or whose leaves are severed is invalid. One that has shriveled or lost some of its leaves, or one grown in a naturally watered soil, is valid.[164]

Rabbi Ishmael taught that one must have three myrtle-branches, two willow-branches, one palm-branch, and one etrog. Even if two of the myrtle-branches have their tips broken off and only one is whole, the lulav set is valid. Rabbi Tarfon taught that even if all three have their tips broken off, the set is valid. Rabbi Akiva taught that just as it is necessary to have only one palm-branch and one etrog, so it is necessary to have only one myrtle-branch and one willow-branch.[165]

The Mishnah taught that an etrog that is stolen or withered is invalid.[166] If the larger part of it is covered with scars, or if its nipple is removed, if it is peeled, split, perforated, so that any part is missing, it is invalid. If only its lesser part is covered with scars, if its stalk was missing, or if it is perforated but nothing of it is missing, it is valid. A dark-colored etrog is invalid. If it is green as a leek, Rabbi Meir declares it valid and Rabbi Judah declares it invalid.[167] Rabbi Meir taught that the minimum size of an etrog is that of a nut. Rabbi Judah taught that it is that of an egg. Rabbi Judah taught that the maximum size is such that two can be held in one hand. Rabbi Jose said even one that can be hold only in both hands.[168]

The Mishnah taught that the absence of one the four kinds of plants used for the lulav — the palm-branch, the etrog, the myrtle, or the willow — invalidates the others.[169] The Gemara explained that this is because Leviticus 23:40 says, "And you shall take," signifying the taking of them all together. Rav Hanan bar Abba argued that one who has all of the four species fulfills the requirement even if one does not take them in hand bound together. They raised an objection from a Baraita that taught: Of the four kinds used for the lulav, two — the etrog and the palm — are fruit-bearing, and two — the myrtle and the willow — are not. Those that bear fruit must be joined with those that do not bear fruit, and those that do not bear fruit must be joined with those that bear fruit. Thus a person does not fulfill the obligation unless they are all bound in one bundle. And so it is, the Baraita taught, with Israel's conciliation with God: It is achieved only when the people of Israel are united as one group.[170]

Rabbi Mani taught that Psalm 35:10, "All my bones shall say: ‘Lord, who is like You?’" alludes to the lulav. The rib of the lulav resembles the spine; the myrtle resembles the eye; the willow resembles the mouth; and the etrog resembles the heart. The Psalmist teaches that no parts of the body are greater than these, which outweigh in importance the rest of the body.[171]

The Gemara taught that one who prepares a lulav recites the blessing, ". . . Who has given us life, has sustained us, and has enabled us to reach this season." When one takes the lulav to fulfill the obligation under Leviticus 23:40, one recites: ". . . Who has sanctified us with Your commandments and has commanded us concerning the taking of the lulav." One who makes a sukkah recites: "Blessed are You, O Lord . . . Who has given us life, has sustained us, and has enabled us to reach this season." When one enters to sit in a sukkah, one recites: "Blessed are You . . . Who has sanctified us with Your commandments and has commanded us to sit in the sukkah."[172]

The Gemara imagined God telling the nations in a time to come that God's command in Leviticus 23:42 to dwell in a sukkah is an easy command, which they should go and carry out.[173]

Rabbi Eliezer taught that during the seven days of Sukkot, one must eat 14 meals in a sukkah — one on each day and one on each night. The Sages of the Mishnah, however, taught that one is not required to eat a fixed number of meals a sukkah, except that one must eat a meal in a sukkah on the first night of Sukkot. Rabbi Eliezer said in addition that if one did not eat in a sukkah on the first night of Sukkot, one may make up for it on the last night of the Festival. The Sages of the Mishnah, however, taught that there is no making up for this, and of this Ecclesiastes 1:15 said: "That which is crooked cannot be made straight, and that which is wanting cannot be numbered."[174] The Gemara explained that Rabbi Eliezer said that one needs to eat 14 meals because the words of Leviticus 23:42, "You shall dwell," imply that one should dwell just as one normally dwells. And so, just as in a normal dwelling, one has one meal by day and one by night, so in the sukkah, one should have one meal by day and one by night. And the Gemara explained that the Sages taught that Leviticus 23:42, "You shall dwell," implies that just as in one's dwelling, one eats if one wishes, and does not eat if one does not wish, so also with a sukkah one eats only if one wishes. But if so, the Gemara asked, why is the meal on the first night mandatory? Rabbi Johanan answered in the name of Rabbi Simeon ben Jehozadak that with regard to Sukkot, Leviticus 23:39 says "the fifteenth," just as Leviticus 23:6 says "the fifteenth" with regard to Passover (implying similarity in the laws for the two Festivals). And for Passover, Exodus 12:18 says, "At evening you shall eat unleavened bread," indicatiung that only the first night is obligatory (to eat unleavened bread).[175] So also for Sukkot, the only first night is also obligatory (to eat in the sukkah). The Gemara then reported that Bira said in the name of Rabbi Ammi that Rabbi Eliezer recanted his statement that one is obliged to eat 14 meals in the sukkah, and changed his position to agree with the Sages. The Gemara taught that a desert later in the holiday may be regarded as a compensating meal to fulfill one's obligation to eat the first meal.[176]

| Day | Verse | Bulls |

|---|---|---|

| Day 1 | Numbers 29:13 | 13 |

| Day 2 | Numbers 29:17 | 12 |

| Day 3 | Numbers 29:20 | 11 |

| Day 4 | Numbers 29:23 | 10 |

| Day 5 | Numbers 29:26 | 9 |

| Day 6 | Numbers 29:29 | 8 |

| Day 7 | Numbers 29:32 | 7 |

| Total | Numbers 29:12–34 | 70 |

Noting that Numbers 29:12–34 required the priests to offer 70 bulls over the seven days of Sukkot, Rabbi Eleazar taught that the 70 bulls correspond to the 70 nations of the world. And Rabbi Eleazar taught that the single bull that Numbers 29:36 required the priests to offer on Shemini Atzeret corresponds to the unique nation of Israel. Rabbi Eleazar compared this to a mortal king who told his servants to prepare a great banquet, but on the last day told his beloved friend to prepare a simple meal so that the king might enjoy his friend's company.[177] Similarly, a Midrash taught that on Sukkot, the Israelites offered God 70 bulls as an atonement for the 70 nations. The Israelites then complained to God that they had offered 70 bulls on behalf of the nations of the world, and they ought thus to love Israel, but they still hated the Jews. As Psalm 109:4 says, "In return for my love they are my adversaries." So in Numbers 29:36, God told Israel to offer a single bull as sacrifice on its own behalf. And the Midrash compared this to the case of a king who made a banquet for seven days and invited all the people in the province. And when the seven days of the feast were over, he said to his friend that he had done his duty to all the people of the province, now the two of them would eat whatever the friend could find — a pound of meat, fish, or vegetables.[178]

Noting that the number of sacrifices in Numbers 29:12–34 decreases each day of Sukkot, a Midrash taught that the Torah thus teaches etiquette from the sacrifices. If a person stays as a friend's house, on the first day, the host entertains generously and serves poultry, on the second day meat, on the third day fish, on the fourth day vegetables, and so the host continually reduces the fare until the host serves the guest beans.[179]

In medieval Jewish interpretation

The parashah is discussed in these medieval Jewish sources:[180]

Numbers chapter 25