Cucurbita

| Cucurbita | |

|---|---|

| |

| Cucurbita fruits come in an assortment of colors and sizes. | |

| Scientific classification | |

| Kingdom: | Plantae |

| Clade: | Angiosperms |

| Clade: | Eudicots |

| Clade: | Rosids |

| Order: | Cucurbitales |

| Family: | Cucurbitaceae |

| Tribe: | Cucurbiteae |

| Genus: | Cucurbita L. |

| Synonyms[1] | |

Cucurbita (Latin for gourd)[3] is a genus of herbaceous vines in the gourd family, Cucurbitaceae, also known as cucurbits, native to the Andes and Mesoamerica. Five species are grown worldwide for their edible fruit, variously known as squash, pumpkin, or gourd depending on species, variety, and local parlance,[lower-alpha 1] and for their seeds. First cultivated in the Americas before being brought to Europe by returning explorers after their discovery of the New World, plants in the genus Cucurbita are important sources of human food and oil. Other kinds of gourd, also called bottle-gourds, are native to Africa and belong to the genus Lagenaria, which is in the same family and subfamily as Cucurbita but in a different tribe. These other gourds are used as utensils or vessels, and their young fruits are eaten much like those of Cucurbita species.

Most Cucurbita species are herbaceous vines that grow several meters in length and have tendrils, but non-vining "bush" cultivars of C. pepo and C. maxima have also been developed. The yellow or orange flowers on a Cucurbita plant are of two types: female and male. The female flowers produce the fruit and the male flowers produce pollen. Many North and Central American species are visited by specialist bee pollinators, but other insects with more general feeding habits, such as honey bees, also visit.

The fruits of the genus Cucurbita are good sources of nutrients, such as vitamin A and vitamin C, among other nutrients according to species. The plants also contain other phytochemicals, such as cucurbitin, cucurmosin, and cucurbitacin.

There is debate about the taxonomy of the genus, as the number of accepted species varies from 13 to 30. The five domesticated species are Cucurbita argyrosperma, C. ficifolia, C. maxima, C. moschata, and C. pepo. All of these can be treated as winter squash because the full-grown fruits can be stored for months; however, C. pepo includes some cultivars that are better used only as summer squash.

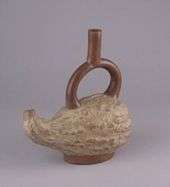

Cucurbita fruits have played a role in human culture for at least 2,000 years. They are often represented in Moche ceramics from Peru. After Christopher Columbus's arrival in the New World, paintings of squashes started to appear in Europe early in the sixteenth century. The fruits have many culinary uses including pumpkin pie, biscuits, bread, desserts, puddings, beverages, and soups. Pumpkins and other Cucurbita fruits are celebrated in festivals and in flower and vegetable shows in many countries.

Description

Cucurbita species fall into two main groups. The first group are annual or short-lived perennial vines and are mesophytic, i.e. they require a more or less continuous water supply. The second group are perennials growing in arid zones and so are xerophytic, tolerating dry conditions. Cultivated Cucurbita species were derived from the first group. Growing 5 to 15 meters (16 to 49 ft) in height or length, the plant stem produces tendrils to help it climb adjacent plants and structures or extend along the ground. Most species do not readily root from the nodes; a notable exception is C. ficifolia, and the four other cultivated mesophytes do this to a lesser extent. The vine of the perennial Cucurbita can become semiwoody if left to grow. There is wide variation in size, shape, and color among Cucurbita fruits, and even within a single species. C. ficifolia is an exception, being highly uniform in appearance.[5] The morphological variation in the species C. pepo[6] and C. maxima[7] is so vast that its various subspecies and cultivars have been misidentified as totally separate species.[6]

The typical cultivated Cucurbita species has five-lobed or palmately divided leaves with long petioles, with the leaves alternately arranged on the stem. The stems in some species are angular. All of the above-ground parts may be hairy with various types of trichomes, which are often hardened and sharp. Spring-like tendrils grow from each node and are branching in some species. C. argyrosperma has ovate-cordate (egg-shaped to heart-shaped) leaves. The shape of C. pepo leaves varies widely. C. moschata plants can have light or dense pubescence. C. ficifolia leaves are slightly angular and have light pubescence. The leaves of all four of these species may or may not have white spots.[8]

There are male (staminate) and female (pistillate) flowers (unisexual flowers) on a single plant (monoecious), and these grow singly, appearing from the leaf axils. Flowers have five fused yellow to orange petals (the corolla) and a green bell-shaped calyx. Male flowers in Cucurbitaceae generally have five stamens, but in Cucurbita there are only three, and their anthers are joined together so that there appears to be one.[9][10] Female flowers have thick pedicels, and an inferior ovary with 3–5 stigmas that each have two lobes.[8][11] The female flowers of C. argyrosperma and C. ficifolia have larger corollas than the male flowers.[8] Female flowers of C. pepo have a small calyx, but the calyx of C. moschata male flowers is comparatively short.[8]

_Madrid_Botanico.jpg)

Cucurbita fruits are large and fleshy.[9] Botanists classify the Cucurbita fruit as a pepo, which is a special type of berry derived from an inferior ovary, with a thick outer wall or rind with hypanthium tissue forming an exocarp around the ovary, and a fleshy interior composed of mesocarp and endocarp. The term "pepo" is used primarily for Cucurbitaceae fruits, where this fruit type is common, but the fruits of Passiflora and Carica are sometimes also pepos.[12][13] The seeds, which are attached to the ovary wall (parietal placentation) and not to the center, are large and fairly flat with a large embryo that consists almost entirely of two cotyledons.[11] Fruit size varies considerably: wild fruit specimens can be as small as 4 centimeters (1.6 in) and some domesticated specimens can weigh well over 300 kilograms (660 lb).[8] The current world record was set in 2014 by Beni Meier of Switzerland with a 2,323.7-pound (1,054.0 kg) pumpkin.[14]

Taxonomy

Cucurbita was formally described in a way that meets the requirements of modern botanical nomenclature by Linnaeus in his Genera Plantarum,[15] the fifth edition of 1754 in conjunction with the 1753 first edition of Species Plantarum.[16] Cucurbita pepo is the type species of the genus.[16][17] Linnaeus initially included the species C. pepo, C. verrucosa and C. melopepo (both now included in C. pepo), as well as C. citrullus (watermelon, now Citrullus lanatus) and C. lagenaria (now Lagenaria siceraria) (both are not Cucurbita but are in the family Cucurbitaceae.[18]

The Cucurbita digitata, C. foetidissima, C. galeotti, and C. pedatifolia species groups are xerophytes, arid zone perennials with storage roots; the remainder, including the five domesticated species, are all mesophytic annuals or short-life perennials with no storage roots.[5][19] The five domesticated species are mostly isolated from each other by sterility barriers and have different physiological characteristics.[19] Some cross pollinations can occur: C. pepo with C. argyrosperma and C. moschata; and C. maxima with C. moschata. Cross pollination does occur readily within the family Cucurbitaceae.[20][21] The buffalo gourd (C. foetidissima), which does not taste good, has been used as an intermediary as it can be crossed with all the common Cucurbita.[11]

Various taxonomic treatments have been proposed for Cucurbita, ranging from 13–30 species.[3] In 1990, Cucurbita expert Michael Nee classified them into the following oft-cited 13 species groups (27 species total), listed by group and alphabetically, with geographic origin:[5][22][23][24]

- C. argyrosperma (synonym C. mixta) – cushaw pumpkin; origin: Panama, Mexico

- C. kellyana, origin: Pacific coast of western Mexico

- C. palmeri, origin: Pacific coast of northwestern Mexico

- C. sororia, origin: Pacific coast Mexico to Nicaragua, northeastern Mexico

- C. digitata – fingerleaf gourd; origin: southwestern United States (USA), northwestern Mexico

- C. ecuadorensis, origin: Ecuador's Pacific coast

- C. ficifolia – figleaf gourd, chilacayote; origin: Mexico, Panama, northern Chile and Argentina

- C. foetidissima – stinking gourd, buffalo gourd; origin: Mexico

- C. scabridifolia, likely a natural hybrid of C. foetidissima and C. pedatifolia[25][26]

- C. galeottii is little known; origin: Oaxaca, Mexico

- C. lundelliana, origin: Mexico, Guatemala, Belize

- C. maxima – winter squash, pumpkin; origin: Argentina, Bolivia, Ecuador

- C. andreana, origin – Argentina

- C. moschata – butternut squash, 'Dickinson' pumpkin, golden cushaw; origin: Bolivia, Colombia, Ecuador, Mexico, Panama, Puerto Rico, Venezuela

- C. okeechobeensis, origin: Florida

- C. martinezii, origin: Mexican Gulf Coast and foothills

- C. pedatifolia, origin: Querétaro, Mexico

- C. pepo – field pumpkin, summer squash, zucchini, vegetable marrow, courgette, acorn squash; origin: Mexico, USA

- C. fraterna, origin: Tamaulipas and Nuevo León, Mexico

- C. texana, origin: Texas, USA

- C. radicans – calabacilla, calabaza de coyote; origin: Central Mexico

The taxonomy by Nee closely matches the species groupings reported in a pair of studies by a botanical team led by Rhodes and Bemis in 1968 and 1970 based on statistical groupings of several phenotypic traits of 21 species. Seeds for studying additional species members were not available. Sixteen of the 21 species were grouped into five clusters with the remaining five being classified separately:[27][28]

- C. digitata, C. palmata, C. californica, C. cylindrata, C. cordata

- C. martinezii, C. okeechobeensis, C. lundelliana

- C. sororia, C. gracilior, C. palmeri; C. argyrosperma (reported as C. mixta) was considered close to the three previous species

- C. maxima, C. andreana

- C. pepo, C. texana

- C. moschata, C. ficifolia, C. pedatifolia, C. foetidissima, and C. ecuadorensis were placed in their own separate species groups as they were not considered significantly close to any of the other species studied.

Phylogeny

The full phylogeny of this genus is unknown, and research was ongoing in 2014.[29][30] The following cladogram of Cucurbita phylogeny is based upon a 2002 study of mitochondrial DNA by Sanjur and colleagues.[31]

| |

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| |

Reproductive biology

All species of Cucurbita have 20 pairs of chromosomes.[27] Many North and Central American species are visited by specialist pollinators in the apid tribe Eucerini, especially the genera Peponapis and Xenoglossa, and these squash bees can be crucial to the flowers producing fruit after pollination.[5][32][33]

_-_male_flower%2C_some_petals_and_1_filament_removed.jpg)

When there is more pollen applied to the stigma, more seeds are produced in the fruits and the fruits are larger with greater likelihood of maturation,[34] an effect called xenia. Competitively grown specimens are therefore often hand-pollinated to maximize the number of seeds in the fruit, which increases the fruit size; this pollination requires skilled technique.[35][36] Seedlessness is known to occur in certain cultivars of C. pepo.[37][38]

The most critical factors in flowering and fruit set are physiological, having to do with the age of the plant and whether it already has developing fruit.[39] The plant hormones ethylene and auxin are key in fruit set and development.[40] Ethylene promotes the production of female flowers. When a plant already has a fruit developing, subsequent female flowers on the plant are less likely to mature, a phenomenon called "first-fruit dominance",[39] and male flowers are more frequent, an effect that appears due to reduced natural ethylene production within the plant stem.[41] Ethephon, a plant growth regulator product that is converted to ethylene after metabolism by the plant, can be used to increase fruit and seed production.[35][42]

The plant hormone gibberellin, produced in the stamens, is essential for the development of all parts of the male flowers. The development of female flowers is not yet understood.[43] Gibberellin is also involved in other developmental processes of plants such as seed and stem growth.[44]

Germination and seedling growth

Seeds with maximum germination potential develop (in C. moschata) by 45 days after anthesis, and seed weight reaches its maximum 70 days after anthesis.[45] Some varieties of C. pepo germinate best with eight hours of sunlight daily and a planting depth of 1.2 centimeters (0.47 in). Seeds planted deeper than 12.5 centimeters (4.9 in) are not likely to germinate.[46] In C. foetidissima, a weedy species, plants younger than 19 days old are not able to sprout from the roots after removing the shoots. In a seed batch with 90 percent germination rate, over 90 percent of the plants had sprouted after 29 days from planting.[47]

Experiments have shown that when more pollen is applied to the stigma, as well as the fruit containing more seeds and being larger (the xenia effect mentioned above), the germination of the seeds is also faster and more likely, and the seedlings are larger.[34] Various combinations of mineral nutrients and light have a significant effect during the various stages of plant growth. These effects vary significantly between the different species of Cucurbita. A type of stored phosphorus called phytate forms in seed tissues as spherical crystalline intrusions in protein bodies called globoids. Along with other nutrients, phytate is used completely during seedling growth.[48] Heavy metal contamination, including cadmium, has a significant negative impact on plant growth.[49] Cucurbita plants grown in the spring tend to grow larger than those grown in the autumn.[50]

Distribution and habitat

Archaeological investigations have found evidence of domestication of Cucurbita going back over 8,000 years from the very southern parts of Canada down to Argentina and Chile. Centers of domestication stretch from the Mississippi River watershed and Texas down through Mexico and Central America to northern and western South America.[5] Of the 27 species that Nee delineates, five are domesticated. Four of them, C. argyrosperma, C. ficifolia, C. moschata, and C. pepo, originated and were domesticated in Mesoamerica; for the fifth, C. maxima, these events occurred in South America.[8]

Within C. pepo, the pumpkins, the scallops, and possibly the crooknecks are ancient and were domesticated at different times and places. The domesticated forms of C. pepo have larger fruits than non-domesticated forms and seeds that are bigger but fewer in number.[51] In a 1989 study on the origins and development of C. pepo, botanist Harry Paris suggested that the original wild specimen had a small round fruit and that the modern pumpkin is its direct descendant. He suggested that the crookneck, ornamental gourd, and scallop are early variants and that the acorn is a cross between the scallop and the pumpkin.[51]

C. argyrosperma is not as widespread as the other species. The wild form C. a. subsp. sororia is found from Mexico to Nicaragua, and cultivated forms are used in a somewhat wider area stretching from Panama to the southeastern United States.[8] It was probably bred for its seeds, which are large and high in oil and protein, but its flesh is of poorer quality than that of C. moschata and C. pepo. It is grown in a wide altitudinal range: from sea level to as high as 1,800 meters (5,900 ft) in dry areas, usually with the use of irrigation, or in areas with a defined rainy season, where seeds are sown in May and June.[8]

C. ficifolia and C. moschata were originally thought to be Asiatic in origin, but this has been disproven. The origin of C. ficifolia is Latin America, most likely southern Mexico, Central America, or the Andes. It grows at altitudes ranging from 1,000 meters (3,300 ft) to 3,000 meters (9,800 ft) in areas with heavy rainfall. It does not hybridize well with the other cultivated species as it has significantly different enzymes and chromosomes.[8]

C. maxima originated in South America over 4,000 years ago,[31] probably in Argentina and Uruguay. The plants are sensitive to frost, and they prefer both bright sunlight and soil with a pH of 6.0 to 7.0.[52] C. maxima did not start to spread into North America until after the arrival of Columbus. Varieties were in use by native peoples of the United States by the 16th century.[5] Types of C. maxima include triloba,[53] zapallito,[54] zipinka,[55] Banana, Delicious, Hubbard, Marrow (C. maxima Marrow), Show, and Turban.[56]

C. moschata is native to Latin America, but the precise location of origin is uncertain.[57] It has been present in Mexico, Belize, Guatemala, and Peru for 4,000–6,000 years and has spread to Bolivia, Ecuador, Panama, Puerto Rico, and Venezuela. This species is closely related to C. argyrosperma. A variety known as the Seminole Pumpkin has been cultivated in Florida since before the arrival of Columbus. Its leaves are 20 to 30 centimeters (8 to 12 in) wide. It generally grows at low altitudes in hot climates with heavy rainfall, but some varieties have been found above 2,200 meters (7,200 ft).[8] Groups of C. moschata include Cheese, Crookneck (C. moschata), and Bell.[56]

C. pepo is one of the oldest, if not the oldest, domesticated species with the oldest known locations being Oaxaca, Mexico, 8,000–10,000 years ago, and Ocampo, Tamaulipas, Mexico, about 7,000 years ago. It is known to have appeared in Missouri, United States, at least 4,000 years ago.[5][8][58][59] Debates about the origin of C. pepo have been on-going since at least 1857.[60] There have traditionally been two opposing theories about its origin: 1) that it is a direct descendant of C. texana and 2) that C. texana is merely feral C. pepo.[5] A more recent theory by botanist Thomas Andres in 1987 is that descendants of C. fraterna hybridized with C. texana,[61] resulting in two distinct domestication events in two different areas: one in Mexico and one in the eastern United States, with C. fraterna and C. texana, respectively, as the ancestral species.[8][31][61][62] C. pepo may have appeared in the Old World before moving from Mexico into South America.[8] It is found from sea level to slightly above 2,000 meters (6,600 ft). Leaves have 3–5 lobes and are 20–35 centimeters (8–14 in) wide. All the subspecies, varieties, and cultivars are interfertile.[6] In 1986 Paris proposed a revised taxonomy of the edible cultivated C. pepo based primarily on the shape of the fruit, with eight groups .[51][63] All but a few C. pepo cultivars can be included in these groups.[8][63][64][65] There is one non-edible cultivated variety: C. pepo var. ovifera.[66]

| Cultivar group | Botanical name | Image | Description |

|---|---|---|---|

| Acorn | C. pepo var. turbinata |  | Winter squash, both a shrubby and creeping plant, obovoid or conical shape, pointed at the apex and with longitudinal grooves, thus resembling a spinning top,[63] ex: Acorn squash[8][64][65] |

| Cocozzelle | C. pepo var. Ionga |  | Summer squash, long round slender fruit that is slightly bulbous at the apex,[63] similar to fastigata, ex: Cocozelle von tripolis[8][64][65] |

| Crookneck | C. pepo var. torticollia (also torticollis) |  | Summer squash, shrubby plant, with yellow, golden, or white fruit which is long and curved at the end and generally has a verrucose (wart-covered) rind,[63] ex: Crookneck squash[8][64][65] |

| Pumpkin | C. pepo var. pepo |  | Winter squash, creeping plant, round, oblate, or oval shape and round or flat on the ends,[63] ex: Pumpkin;[8][64][65] includes C. pepo subsp. pepo var. styriaca, used for Styrian pumpkin seed oil[67] |

| Scallop | C. pepo var. clypeata; called C. melopepo by Linnaeus[6] |  | Summer squash, prefers half-shrubby habitat, flattened or slightly discoidal shape, with undulations or equatorial edges,[63] ex: Pattypan squash[8][64][65] |

| Straightneck | C. pepo var. recticollis |  | Summer squash, shrubby plant, with yellow or golden fruit and verrucose rind, similar to var. torticollia but a stem end that narrows,[63] ex: Straightneck squash[8][64][65] |

| Vegetable marrow | C. pepo var. fastigata |  | Summer and winter squashes, creeper traits and a semi-shrub, cream to dark green color, short round fruit with a slightly broad apex,[63] ex: Spaghetti squash (a winter variety)[8][64][65] |

| Zucchini/Courgette | C. pepo var. cylindrica | | Summer squash, presently the most common group of cultivars, origin is recent (19th century), semi-shrubby, cylindrical fruit with a mostly consistent diameter,[63] similar to fastigata, ex: Zucchini[8][64][65] |

| Ornamental gourds | C. pepo var. ovifera | .jpg) | Non-edible,[66] field squash closely related to C. texana, vine habitat, thin stems, small leaves, three sub-groups: C. pepo var. ovifera (egg-shaped, pear-shaped), C. pepo var. aurantia (orange color), and C. pepo var. verrucosa (round warty gourds), ornamental gourds found in Texas and called var. texana and ornamental gourds found outside of Texas (Illinois, Missouri, Arkansas, Oklahoma, and Louisiana) are called var. ozarkana.[58] |

History and domestication

The ancestral species of the genus Cucurbita were present in the Americas before the arrival of humans,[68][69] and are native to the New World. The likely center of origin is southern Mexico, spreading south through what is now known as Mesoamerica, on into South America, and north to what is now the southwestern United States.[68] Evolutionarily speaking, the genus is relatively recent in origin, dating back only to the Holocene, whereas the family Cucurbitaceae, in the shape of seeds similar to Bryonia, dates to the Paleocene.[70] No species within the genus is entirely genetically isolated. C. moschata can intercross with all the others, though the hybrid offspring may not themselves be fertile unless they become polyploid.[19] The genus was part of the culture of almost every native peoples group from southern South America to southern Canada.[69] Modern-day cultivated Cucurbita are not found in the wild.[5] Genetic studies of the mitochondrial gene nad1 show there were at least six independent domestication events of Cucurbita separating domestic species from their wild ancestors.[31] Species native to North America include C. digitata (calabazilla),[71] and C. foetidissima (buffalo gourd),[72] C. palmata (coyote melon), and C. pepo.[5] Some species, such as C. digitata and C. ficifolia, are referred to as gourds. Gourds, also called bottle-gourds, which are used as utensils or vessels, belong to the genus Lagenaria and are native to Africa. Lagenaria are in the same family and subfamily as Cucurbita but in a different tribe.[73]

The earliest known evidence of the domestication of Cucurbita dates back at least 8,000 years ago, predating the domestication of other crops such as maize and beans in the region by about 4,000 years.[5][58][59][74] This evidence was found in the Guilá Naquitz cave in Oaxaca, Mexico, during a series of excavations in the 1960s and 1970s, possibly beginning in 1959.[75][76] Solid evidence of domesticated C. pepo was found in the Guilá Naquitz cave in the form of increasing rind thickness and larger peduncles in the newer stratification layers of the cave. By c. 8,000 years BP the C. pepo peduncles found are consistently more than 10 millimeters (0.39 in) thick. Wild Cucurbita peduncles are always below this 10 mm barrier. Changes in fruit shape and color indicate that intentional breeding of C. pepo had occurred by no later than 8,000 years BP.[11][77][78] During the same time frame, average rind thickness increased from 0.84 millimeters (0.033 in) to 1.15 millimeters (0.045 in).[79]

Squash was domesticated first, followed by maize and then beans, becoming part of the Three Sisters agricultural system of companion planting.[80][81] The English word "squash" derives from askutasquash (a green thing eaten raw), a word from the Narragansett language, which was documented by Roger Williams, the founder of Rhode Island, in his 1643 publication A Key Into the Language of America.[82] Similar words for squash exist in related languages of the Algonquian family.[51][83]

Production

The family Cucurbitaceae has many species used as human food.[8] Cucurbita is one of the most important of those, with the various species being prepared and eaten in many ways. Although the stems and skins tend to be more bitter than the flesh,[84][85] the fruits and seeds of cultivated varieties are quite edible and need little or no preparation. The flowers and young leaves and shoot tips can also be consumed.[86] The seeds and fruits of most varieties can be stored for long periods of time,[5] particularly the sweet-tasting winter varieties with their thick, inedible skins. Summer squash have a thin, edible skin. The seeds of both types can be roasted, eaten raw, made into pumpkin seed oil,[67] ground into a flour or meal,[87] or otherwise prepared.

Squashes are primarily grown for the fresh food market.[88] The Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations (FAO) reported that the ranking of the top five squash-producing countries was stable between 2005 and 2009. Those countries are: China, India, Russia, the United States, and Egypt. By 2012, Iran had moved into the 5th slot, with Egypt falling to 6th. The top 10 countries in terms of metric tons of squashes produced are:[89]

| Country | Production (metric tons) |

|---|---|

| 6,140,840 | |

| |

4,424,200 |

| 988,180 | |

| 778,630 | |

| 695,600 | |

| 658,234 | |

| 522,388 | |

| 516,900 | |

| 508,075 | |

| 430,402 | |

| Top 10 total | 15,663,449 |

The only additional countries that rank in the top 20 where squashes are native are Cuba, which ranks 14th with 347,082 metric tons, and Argentina, which ranks 17th, with 326,900 metric tons.[89] In addition to being the 4th largest producer of squashes in the world, the United States is the world's largest importer of squashes, importing 271,614 metric tons in 2011, 95 percent of that from Mexico. Within the United States, the states producing the largest amounts are Florida, New York, California, and North Carolina.[88]

This is how Cucurbita compares to several other major Cucurbitaceae crops in terms of crop tonnage harvested:

| Country | Production (metric tons) |

|---|---|

| |

40,710,200 |

| |

1,811,630 |

| |

1,739,190 |

| |

1,161,870 |

| |

883,360 |

| |

860,100 |

| |

682,900 |

| |

631,408 |

| |

587,800 |

| |

547,141 |

| Top 10 total | 49,075,599 |

| Country | Production (metric tons) |

|---|---|

| |

56,649,725 |

| |

3,683,100 |

| |

3,466,880 |

| |

1,870,400 |

| |

1,866,660 |

| |

1,637,090 |

| |

1,182,400 |

| |

1,151,580 |

| |

1,036,800 |

| |

946,200 |

| Top 10 total | 73,490,835 |

Nutrients

| Nutritional value per 100 g (3.5 oz) | |

|---|---|

| Energy | 69 kJ (16 kcal) |

|

3.4 g | |

| Sugars | 2.2 g |

| Dietary fiber | 1.1 g |

|

0.2 g | |

|

1.2 g | |

| Vitamins | |

| Vitamin A equiv. |

(1%) 10 μg (1%) 120 μg2125 μg |

| Thiamine (B1) |

(4%) 0.048 mg |

| Riboflavin (B2) |

(12%) 0.142 mg |

| Niacin (B3) |

(3%) 0.487 mg |

| Pantothenic acid (B5) |

(3%) 0.155 mg |

| Vitamin B6 |

(17%) 0.218 mg |

| Folate (B9) |

(7%) 29 μg |

| Vitamin C |

(20%) 17 mg |

| Vitamin K |

(3%) 3 μg |

| Minerals | |

| Iron |

(3%) 0.35 mg |

| Magnesium |

(5%) 17 mg |

| Manganese |

(8%) 0.175 mg |

| Phosphorus |

(5%) 38 mg |

| Potassium |

(6%) 262 mg |

| Zinc |

(3%) 0.29 mg |

| Other constituents | |

| Water | 95 g |

|

Link to USDA Database entry, for comparison, see values for raw pumpkin | |

| |

|

Percentages are roughly approximated using US recommendations for adults. Source: USDA Nutrient Database | |

As an example of Curcubita, raw summer squash is 94% water, 3% carbohydrates, and 1% protein, with negligible fat content (table). In 100 grams, raw squash supplies 16 calories and is rich in vitamin C (20% of the Daily Value, DV), moderate in vitamin B6 and riboflavin (12-17% DV), but otherwise devoid of appreciable nutrient content (table), although the nutrient content of different Curcubita species may vary somewhat.[90]

Pumpkin seeds contain vitamin E, crude protein, B vitamins and several dietary minerals (see nutrition table at pepita).[91] Also present in pumpkin seeds are unsaturated and saturated oils, palmitic, oleic and linoleic fatty acids,[92] as well as carotenoids.[93]

Toxins

Cucurbitin is an amino acid and a carboxypyrrolidine that is found in raw Cucurbita seeds.[94][95] It retards the development of parasitic flukes when administered to infected host mice, although the effect is only seen if administration begins immediately after infection.[96]

Cucurmosin is a ribosome inactivating protein found in the flesh and seed of Cucurbita,[97][98] notably Cucurbita moschata. Cucurmosin is more toxic to cancer cells than healthy cells.[97][99]

Cucurbitacin is a plant steroid present in wild Cucurbita and in each member of the family Cucurbitaceae. Poisonous to mammals,[100] it is found in quantities sufficient to discourage herbivores. It makes wild Cucurbita and most ornamental gourds, with the exception of an occasional C. fraterna and C. sororia, bitter to taste.[3][61][101] Ingesting too much cucurbitacin can cause stomach cramps, diarrhea and even collapse.[84] This bitterness is especially prevalent in wild Cucurbita; in parts of Mexico the flesh of the fruits is rubbed on a woman's breast to wean children.[102] While the process of domestication has largely removed the bitterness from cultivated varieties,[3] there are occasional reports of cucurbitacin causing illness in humans.[3] Cucurbitacin is also used as a lure in insect traps.[101]

Pests and diseases

Cucurbita species are used as food plants by the larvae of some Lepidoptera species, including the Cabbage Moth (Mamestra brassicae), Hypercompe indecisa, and the Turnip Moth (Agrotis segetum).[103] Cucurbita can be susceptible to the pest Bemisia argentifolii (silverleaf whitefly)[104] as well as aphids (Aphididae), cucumber beetles (Acalymma vittatum and Diabrotica undecimpunctata howardi), squash bug (Anasa tristis), the squash vine borer (Melittia cucurbitae), and the twospotted spidermite (Tetranychus urticae).[105] The squash bug causes major damage to plants because of its very toxic saliva.[106] The red pumpkin beetle (Raphidopalpa foveicollis) is a serious pest of cucurbits, especially the pumpkin, which it can defoliate.[107] Cucurbits are susceptible to diseases such as bacterial wilt (Erwinia tracheiphila), anthracnose (Colletotrichum spp.), fusarium wilt (Fusarium spp.), phytophthora blight (Phytophthora spp. water molds), and powdery mildew (Erysiphe spp.).[105] Defensive responses to viral, fungal, and bacterial leaf pathogens do not involve cucurbitacin.[100]

Species in the genus Cucurbita are susceptible to some types of mosaic virus including: Cucumber mosaic virus (CMV), Papaya ringspot virus-cucurbit strain (PRSV), Squash mosaic virus (SqMV), Tobacco ringspot virus (TRSV),[108] Watermelon mosaic virus (WMV), and Zucchini yellow mosaic virus (ZYMV).[109][110][111][112] PRSV is the only one of these viruses that does not affect all cucurbits.[109][113] SqMV and CMV are the most common viruses among cucurbits.[114][115] Symptoms of these viruses show a high degree of similarity, which often results in laboratory investigation being needed to differentiate which one is affecting plants.[108]

Human culture

Art, music, and literature

Along with maize and beans, squash has been depicted in the art work of the native peoples of the Americas for at least 2,000 years.[116][117] For example, cucurbits are often represented in Moche ceramics.[116][118]

Though native to the western hemisphere, Cucurbita began to spread to other parts of the world after Christopher Columbus's arrival in the New World in 1492.[119][120] Until recently, the earliest known depictions of this genus in Europe was of Cucurbita pepo in De Historia Stirpium Commentarii Insignes in 1542 by the German botanist Leonhart Fuchs, but in 1992, two paintings, one of C. pepo and one of C. maxima, painted between 1515 and 1518, were identified in festoons at Villa Farnesina in Rome.[121] Also, in 2001 depictions of this genus were identified in Grandes Heures of Anne of Brittany (Les Grandes Heures d'Anne de Bretagne), a French devotional book, an illuminated manuscript created between 1503 and 1508. This book contains an illustration known as Quegourdes de turquie, which was identified by cucurbit specialists as C. pepo subsp. texana in 2006.[122]

In 1952, Stanley Smith Master, using the pen name Edrich Siebert, wrote "The Marrow Song (Oh what a beauty!)" to a tune in 6/8 time. It became a popular hit in Australia in 1973,[123] and was revived by the Wurzels in Britain on their 2003 album Cutler of the West.[124][125] John Greenleaf Whittier wrote a poem entitled The Pumpkin in 1850.[126] "The Great Pumpkin" is a fictional holiday figure in the comic strip Peanuts by Charles M. Schulz.[127]

Soap

The fruit pulp of some species, such as C. foetidissima, can be used as a soap or detergent.[128]

Folk remedies

Cucurbita have been used in various cultures as folk remedies. Pumpkins have been used by Native Americans to treat intestinal worms and urinary ailments. This Native American remedy was adopted by American doctors in the early nineteenth century as an anthelmintic for the expulsion of worms.[129] In southeastern Europe, seeds of C. pepo were used to treat irritable bladder and benign prostatic hyperplasia.[130] In Germany, pumpkin seed is approved for use by the Commission E, which assesses folk and herbal medicine, for irritated bladder conditions and micturition problems of prostatic hyperplasia stages 1 and 2, although the monograph published in 1985 noted a lack of pharmacological studies that could substantiate empirically found clinical activity.[131] The FDA in the United States, on the other hand, banned the sale of all such non-prescription drugs for the treatment of prostate enlargement in 1990.[132]

In China, C. moschata seeds were also used in traditional Chinese medicine for the treatment of the parasitic disease schistosomiasis[133] and for the expulsion of tape worms.[134]

In Mexico, herbalists use C. ficifolia in the belief that it reduces blood sugar levels.[135]

Culinary uses

Long before European contact, Cucurbita had been a major food source for the native peoples of the Americas, and the species became an important food for European settlers, including the Pilgrims, even featuring at the first Thanksgiving.[11] Commercially made pumpkin pie mix is most often made from varieties of C. moschata; 'Libby's Select' uses the Select Dickinson Pumpkin variety of C. moschata for its canned pumpkin.[136] Other foods that can be made using members of this genus include biscuits, bread, cheesecake, desserts, donuts, granola, ice cream, lasagna dishes, pancakes, pudding, pumpkin butter,[137] salads, soups, and stuffing.[138] Squash soup is a dish in African cuisine.[139] The xerophytic species are proving useful in the search for nutritious foods that grow well in arid regions.[140] C. ficifolia is used to make soft and mildly alcoholic drinks.[8]

In India, squashes (ghia) are cooked with seafood such as prawns.[141] In France, marrows (courge) are traditionally served as a gratin, sieved and cooked with butter, milk, and egg, and flavored with salt, pepper, and nutmeg,[142] and as soups. In Italy, zucchini and larger squashes are served in a variety of regional dishes, such as cocuzze alla puviredda cooked with olive oil, salt and herbs from Puglia; as torta di zucca from Liguria, or torta di zucca e riso from Emilia-Romagna, the squashes being made into a pie filling with butter, ricotta, parmesan, egg, and milk; and as a sauce for pasta in dishes like spaghetti alle zucchine from Sicily.[143] In Japan, squashes such as small C. moschata pumpkins (kabocha) are eaten boiled with sesame sauce, fried as a tempura dish, or made into balls with sweet potato and Japanese mountain yam.[144]

Festivals

Cucurbita fruits including pumpkins and marrows are celebrated in festivals in countries such as Argentina, Bolivia,[145] Britain, Canada,[146] Croatia,[147] France,[148][149] Germany, Italy,[150][151][152][153] Japan,[154] Peru,[155] Portugal, Spain,[156] Switzerland,[157] and the United States. Argentina holds an annual nationwide pumpkin festival Fiesta Nacional del Zapallo ("Squashes and Pumpkins National Festival"), in Ceres, Santa Fe,[158] on the last day of which a Reina Nacional del Zapallo ("National Queen of the Pumpkin") is chosen.[159][160][161] In Portugal the Festival da Abóbora de Lourinhã e Atalaia ("Squashes and Pumpkins Festival in Lourinhã and Atalaia") is held in Lourinhã city, called the Capital Nacional da Abóbora (the "National Capital of Squashes and Pumpkins").[162] Ludwigsburg, Germany annually hosts the world's largest pumpkin festival.[163] In Britain a giant marrow (zucchini) weighing 54.3177 kilograms (119.750 lb) was displayed in the Harrogate Autumn Flower Show in 2012.[164] In the USA, pumpkin chucking is practiced competitively, with machines such as trebuchets and air cannons designed to throw intact pumpkins as far as possible.[165][166] The Keene Pumpkin Fest is held annually in New Hampshire; in 2013 it held the world record for the most jack-o-lanterns lit in one place, 30,581 on October 19, 2013.[167]

Halloween is widely celebrated with jack-o-lanterns made of large orange pumpkins carved with ghoulish faces and illuminated from inside with candles.[168] The pumpkins used for jack-o-lanterns are C. pepo,[169][170] not to be confused with the ones typically used for pumpkin pie in the United States, which are C. moschata.[171] Kew Gardens marked Halloween in 2013 with a display of pumpkins, including a towering pyramid made of many varieties of squash, in the Waterlily House during its "IncrEdibles" festival.[172]

See also

- List of gourds and squashes in the genus Cucurbita

Notes

References

- ↑ "Cucurbita L.". Tropicos, Missouri Botanical Garden. Retrieved January 12, 2014.

- ↑ "Tristemon". Tropicos, Missouri Botanical Garden. Retrieved January 14, 2015.

- 1 2 3 4 5 Burrows, George E.; Tyrl, Ronald J. (2013). Toxic Plants of North America. Oxford: Wiley-Blackwell. pp. 389–391. ISBN 978-0-8138-2034-7.

- ↑ Ferriol, María; Picó, Belén (2007). "3". Handbook of Plant Breeding: Vegetables I. New York: Springer. p. 317. ISBN 978-0-387-72291-7.

The common terms "pumpkin", "squash", "gourd", "cushaw", "ayote", "zapallo", "calabaza", etc. are often applied indiscriminately to different cultivated species of the New World genus Cucurbita L. (Cucurbitaceae): C. pepo L., C. maxima Duchesne, C. moschata Duchesne, C. argyrosperma C. Huber and C. ficifolia Bouché.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 Nee, Michael (1990). "The Domestication of Cucurbita (Cucurbitaceae)". Economic Botany. New York: New York Botanical Gardens Press. 44 (3, Supplement: New Perspectives on the Origin and Evolution of New World Domesticated Plants): 56–68. JSTOR 4255271.

- 1 2 3 4 Decker-Walters, Deena S.; Staub, Jack E.; Chung, Sang-Min; Nakata, Eijiro; Quemada, Hector D. (2002). "Diversity in Free-Living Populations of Cucurbita pepo (Cucurbitaceae) as Assessed by Random Amplified Polymorphic DNA". Systematic Botany. American Society of Plant Taxonomists. 27 (1): 19–28. doi:10.2307/3093892. JSTOR 3093892.

- ↑ Millán, R. (1945). "Variaciones del Zapallito Amargo Cucurbita andreana y el Origen de Cucurbita maxima". Revista Argentina de Agronomía (in Spanish). 12: 86–93.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 19 20 21 22 23 24 Saade, R. Lira; Hernández, S. Montes. "Cucurbits". Purdue Horticulture. Retrieved September 2, 2013.

- 1 2 Mabberley, D. J. (2008). The Plant Book: A Portable Dictionary of the Vascular Plants. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. p. 235. ISBN 978-0-521-82071-4.

- ↑ Lu, Anmin; Jeffrey, Charles. "Cucurbita Linnaeus". Flora of China. Retrieved February 21, 2015.

- 1 2 3 4 5 "Cucurbitaceae--Fruits for Peons, Pilgrims, and Pharaohs". University of California at Los Angeles. Archived from the original on October 16, 2013. Retrieved September 2, 2013.

- ↑ "A Systematic Treatment of Fruit Types". Worldbotanical. Retrieved October 10, 2013.

- ↑ Schrager, Victor (2004). The Compleat Squash: A Passionate Grower's Guide to Pumpkins, Squash, and Gourds. New York: Artisan. p. 25. ISBN 978-1-57965-251-7.

- ↑ "2014 - Beni Meier and his 2323.7 pound World Record Giant Pumpkin!". BigPumpkins.com. 2014. Retrieved February 12, 2016.

- ↑ Linnaeus, Carl (1754). "Cucurbita". Genera Plantarum. 1. Stockholm: Impensis Laurentii Salvii via Biodiversity Heritage Library. p. 441.

- 1 2 Linnaeus, Carl (1753). "Cucurbita". Species Plantarum. 2. Stockholm: Impensis Laurentii Salvii via Biodiversity Heritage Library. p. 1010.

- ↑ "Cucurbita". The Linnaean Plant Name Typification Project. Natural History Museum. Retrieved November 4, 2013.

- ↑ "Cucurbita". The Plant List. Retrieved 1 January 2015.

- 1 2 3 Whitaker, T.W.; Bemis, W.P. (1975). "Origin and Evolution of the Cultivated Cucurbita". Bulletin of the Torrey Botanical Club. 102 (6): 362–368. doi:10.2307/2484762. JSTOR 2484762.

- ↑ Janssen, Don (August 14, 2006). "Curbit Family & Cross-Pollination". University of Nebraska - Lincoln. Retrieved January 14, 2015.

- ↑ Rakha, M. T.; Metwally, E. I.; Moustafa, E. A.; Etman, A. A.; Dewir, Y. H. (2012). "Production of Cucurbita Interspecific Hybrids ThroughCross Pollination and Embryo Rescue Technique". World Applied Sciences Journal. 20 (10): 1366–1370.

- ↑ GRIN. "GRIN Species Records of Genus Cucurbita". Taxonomy for Plants. National Germplasm Resources Laboratory, Beltsville, Maryland: USDA, ARS, National Genetic Resources Program. Retrieved September 1, 2013.

- ↑ "Cucurbita". Integrated Taxonomic Information System. Retrieved September 1, 2013.

- ↑ Goldman, Amy (2004). The Compleat Squash: A Passionate Grower's Guide to Pumpkins, Squash, and Gourds. New York: Artisan. p. 77. ISBN 978-1-57965-251-7.

- ↑ Andres, Thomas C. (1987). "Relationship of Cucurbita scabridifolia to C. foetidissima and C. pedatifolia: A Case of Natural Interspecific Hybridization". Cucurbit Genetics Cooperative Report. 10: 74–75.

- ↑ Bailey, Liberty Hyde (1943). "Species of Cucurbita". Gentes Herbarum. 6: 267–322.

- 1 2 Rhodes, A. M.; Bemis, W. P.; Whitaker, Thomas W.; Carmer, S. G. (1968). "A Numerical Taxonomic Study of Cucurbita". Brittonia. New York Botanical Garden Press. 20 (3): 251–266. doi:10.2307/2805450. JSTOR 2805450.

- ↑ Bemis, W. P.; Rhodes, A. M.; Whitaker, Thomas W.; Carmer, S. G. (1970). "Numerical Taxonomy Applied to Cucurbita Relationships". American Journal of Botany. 57 (4): 404–412. doi:10.2307/2440868. JSTOR 2440868.

- ↑ Gon g, L.; Pachner, M.; Kalai, K.; Lelley, T. (November 2008). "SSR-based Genetic Linkage Map of Cucurbita moschata and its Synteny With Cucurbita pepo". Genome. 51 (11): 878–887. doi:10.1139/G08-072. PMID 18956020.

- ↑ Gong, L.; Stift, G.; Koffler, R.; Pachner, M.; Lelley, T. (June 2008). "Microsatellites for the Genus Cucurbita and an SSR-based Genetic Linkage Map of Cucurbita pepo L.". Theoretical and Applied Genetics. 117 (1): 37–48. doi:10.1007/s00122-008-0750-2. PMC 2413107

. PMID 18379753.

. PMID 18379753. - 1 2 3 4 Sanjur, Oris I.; Piperno, Dolores R.; Andres, Thomas C.; Wessel-Beaver, Linda (2002). "Phylogenetic Relationships among Domesticated and Wild Species of Cucurbita (Cucurbitaceae) Inferred from a Mitochondrial Gene: Implications for Crop Plant Evolution and Areas of Origin" (PDF). Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. Washington, DC: National Academy of Sciences. 99 (1): 535–540. doi:10.1073/pnas.012577299. JSTOR 3057572.

- ↑ Hurd, Paul D.; Linsley, E. Gorton (1971). "Squash and Gourd Bees (Peponapis, Xenoglossa) and the Origin of the Cultivated Cucurbita". Evolution. St. Louis, MO: Society for the Study of Evolution. 25 (1): 218–234. doi:10.2307/2406514. JSTOR 2406514.

- ↑ Whitaker, Thomas W.; Bemis, W. P. (1964). "Evolution in the Genus Cucurbita". Evolution. 18 (4): 553–559. doi:10.2307/2406209. JSTOR 2406209.

- 1 2 Winsor, J. A.; Davis, L. E.; Stephenson, A. G. (1987). "The Relationship Between Pollen Load and Fruit Maturation and the Effect of Pollen Load on Offspring Vigor in Cucurbita pepo". The American Naturalist. 129 (5): 643–656. doi:10.1086/284664. JSTOR 2461727.

- 1 2 Robinson, Richard W. (2000). "Rationale and Methods for Producing Hybrid Cucurbit Seed". Journal of New Seeds. 1 (3-4): 1–47. doi:10.1300/J153v01n03_01.

- ↑ Stephenson, Andrew G.; Devlin, B.; Horton, J. Brian (1988). "The Effects of Seed Number and Prior Fruit Dominance on the Pattern of Fruit Production in Cucurbita pepo (Zucchini Squash)". Annals of Botany. 62 (6): 653–661.

- ↑ Robinson, R. W.; Reiners, Stephen (July 1999). "Parthenocarpy in Summer Squash" (PDF). HortScience. 34 (4): 715–717.

- ↑ Menezes, C. B.; Maluf, W. R.; Azevedo, S. M.; Faria, M. V.; Nascimento, I. R.; Gomez, L. A.; Bearzoti, E. (March 2005). "Inheritance of Parthenocarpy in Summer Squash (Cucurbita pepo L.).". Genetics and Molecular Research. 31 (4): 39–46. PMID 15841434.

- 1 2 Stapleton, Suzanne Cady; Wien, H. Chris; Morse, Roger A. (2000). "Flowering and Fruit Set of Pumpkin Cultivars under Field Conditions" (PDF). HortScience. 35 (6): 1074–1077.

- ↑ Martínez, Cecelia; Manzano, Susana; Megías, Zoraida; Garrido, Dolores; Picó, Belén; Jamilena, Manuel (2013). "Involvement of Ethylene Biosynthesis and Signalling in Fruit Set and Early Fruit Development in Zucchini Squash (Cucurbita pepo L.)". BMC Plant Biology. 13 (139). doi:10.1186/1471-2229-13-139.

- ↑ Krupnick, Gary A.; Brown, Kathleen M.; Stephenson, Andrew G. (1999). "The Influence of Fruit on the Regulation of Internal Ethylene Concentrations and Sex Expression in Cucurbita texana". International Journal of Plant Sciences. 160 (2): 321–330. doi:10.1086/314120.

- ↑ Murray, M. (1987). "Field Applications Of Ethephon For Hybrid And Open-Pollinated Squash (Cucurbita Spp) Seed Production". Acta Horticulturae. 201: 149–156.

- ↑ Pimenta Lange, Maria João; Knop, Nicole; Lange, Theo (2012). "Stamen-derived Bioactive Gibberellin is Essential for Male Flower Development of Cucurbita maxima L.". Journal of Experimental Botany. 63 (7): 2681–2691. doi:10.1093/jxb/err448. PMC 3346225

. PMID 22268154.

. PMID 22268154. - ↑ "Plant Hormones". Charles Sturt University. Retrieved January 15, 2014.

- ↑ Wilson, Mack A.; Splittstoesser, Walter E. (1980). "The Relationship Between Embryo Axis Weight and Reserve Protein During Development and Pumpkin Seed Germination". Journal of Seed Technology. 5 (2): 35–41. JSTOR 23432821.

- ↑ Oliver, Lawrence R.; Harrison, Steve A.; McClelland, Marilyn (1983). "Germination of Texas Gourd (Cucurbita texana) and Its Control in Soybeans (Glycine max)". Weed Science. 31 (5): 700–706. JSTOR 4043694.

- ↑ Horak, Michael J.; Sweat, Jonathan K. (1994). "Germination, Emergence, and Seedling Establishment of Buffalo Gourd (Cucurbita foetidissima)". Weed Science. 42 (3): 358–363. JSTOR 4045510.

- ↑ Beecroft, Penny; Lott, John N. A. (1996). "Changes in the Element Composition of Globoids From Cucurbita maxima and Cucurbita andreana Cotyledons During Early Seedling Growth". Canadian Journal of Botany. 74 (6): 838–847. doi:10.1139/b96-104.

- ↑ Subin, M. P.; Francis, Steffy (2013). "Phytotoxic Effects of Cadmium on Seed Germination, Early Seedling Growth and Antioxidant Enzyme Activities in Cucurbita maxima Duchesne". International Research Journal of Biological Sciences. 2 (9): 40–47. doi:10.1139/b96-104.

- ↑ Fenner, G. P.; Patteron, G. W.; Lusby, W. R. (1989). "Developmental Regulation of Sterol Biosynthesis in Cucurbita maxima L.". Lipids. 24 (4): 271–277. doi:10.1007/BF02535162.

- 1 2 3 4 Paris, Harry S. (1989). "Historical Records, Origins, and Development of the Edible Cultivar Groups of Cucurbita pepo (Cucurbitaceae)". Economic Botany. New York Botanical Garden Press. 43 (4): 423–443. doi:10.1007/bf02935916. JSTOR 4255187.

- ↑ "Cucurbita maxima Origin/ Habitat". University of Wisconsin. 2007. Retrieved September 2, 2013.

- ↑ "Holotype of Cucurbita maxima Duchesne var. triloba Millán [family CUCURBITACEAE]". Retrieved October 3, 2013.(subscription required)

- ↑ López-Anido, F.; Cravero, V.; Asprelli, P.; Cointry, E.; Firpo, I.; García, S. M. (2003). "Inheritance of Immature Fruit Color in Cucurbita maxima var. zapallito (Carrière) Millán" (PDF). Cucurbit Genetics Cooperative Report. 26: 48–50.

- ↑ "Holotype of Cucurbita maxima Duchesne var. zipinka Millán [family CUCURBITACEAE]". Retrieved October 3, 2013.(subscription required)

- 1 2 Robinson, Richard Warren; Decker-Walters, D. S. (1997). Cucurbits. Oxfordshire, UK: CAB International. pp. 71–83. ISBN 978-0-85199-133-7.

- ↑ Wessel-Beaver, Linda (2000). "Evidence for the Center of Diversity of Cucurbita moschata in Colombia". Cucurbit Genetics Cooperative Report. 23: 54–55.

- 1 2 3 Wilson, Hugh D. "What is Cucurbita texana?". Free-living Cucurbita pepo in the United States Viral Resistance, Gene Flow, and Risk Assessment. Texas A&M Bioinformatics Working Group. Retrieved September 8, 2013.

- 1 2 Gibbon, Guy E.; Ames, Kenneth M. (1998). Archaeology of Prehistoric Native America: An Encyclopedia. New York: Routledge. p. 238. ISBN 978-0-8153-0725-9.

- ↑ Kirkpatrick, Kurt J.; Wilson, Hugh D. (1988). "Interspecific Gene Flow in Cucurbita: C. texana vs. C. pepo". American Journal of Botany. Botanical Society of America. 75 (4): 519–527. doi:10.2307/2444217.

- 1 2 3 Andres, Thomas C. (1987). "Cucurbita fraterna, the Closest Wild Relative and Progenitor of C. pepo". Cucurbit Genetics Cooperative Report. 10: 69–71.

- ↑ Soltis, Douglas E.; Soltis, Pamela S. (1990). Isozymes in Plant Biology. London: Dioscorodes Press. p. 176. ISBN 978-0-412-36500-3.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 Paris, Harry S. (1986). "A Proposed Subspecific Classification for Cucurbita pepo". Phytologia. 61 (3): 133–138.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 "Cucurbita pepo". Missouri Botanical Garden. Retrieved September 2, 2013.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 Heistinger, Andrea (2013). The Manual of Seed Saving: Harvesting, Storing, and Sowing Techniques for Vegetables, Herbs, and Fruits. Portland, OR: Timber Press. p. 278. ISBN 978-1-60469-382-9.

- 1 2 Decker, Deena S.; Wilson, Hugh D. (1987). "Allozyme Variation in the Cucurbita pepo Complex: C. pepo var. ovifera vs. C. texana". Systematic Botany. American Society of Plant Taxonomists. 12 (2): 263–273. doi:10.2307/2419320. JSTOR 2419320.

- 1 2 Fürnkranz, Michael; Lukesch, Birgit; Müller, Henry; Huss, Herbert; Grube, Martin; Berg, Gabriele (2012). "Microbial Diversity Inside Pumpkins: Microhabitat-Specific Communities Display a High Antagonistic Potential Against Phytopathogens". Microbial Ecology. Springer. 63 (2): 418–428. doi:10.2307/41412429. JSTOR 41412429.

- 1 2 Bemis, W. P.; Whitaker, Thomas W. (April 1969). "The Xerophytic Cucurbita of Northwestern Mexico and Southwestern United States". Madroño. California Botanical Society. 20 (2): 33–41. JSTOR 41423342.

- 1 2 Smith, Bruce D. (15 August 2006). "Eastern North America as an Independent Center of Plant Domestication". Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 103 (33): 12223–12228. doi:10.1073/pnas.0604335103. PMC 1567861

. PMID 16894156.

. PMID 16894156. - ↑ Kubitzki, Klaus (2011). Flowering Plants. Eudicots: Sapindales, Cucurbitales, Myrtaceae. Heidelberg: Springer Science & Business Media. pp. 120–122. ISBN 978-3-642-14397-7.

The fossil record of Cucurbitaceae and indeed of the order Cucurbitales is sparse.. The oldest fossils are seeds from the Uppermost Paleocene and Lower Eocene London Clay (65MA).. Bryonia-like seeds from fossil beda at Tambov, Western Siberia date to the Lower Sarmat, 15-13 MA ago. Subfossil records of Cucurbita pepo have been dated to 8,000-7,000 B.C. at Guila Naquitz ... , those of C. moschata in the northern Peruvian Andes to up to 9,200 B.P.

- ↑ "Cucurbita digitata A. Gray". United States Department of Agriculture. Retrieved September 1, 2013.

- ↑ "Cucurbita ficifolia Bouché". United States Department of Agriculture. Retrieved September 1, 2013.

- ↑ Roberts, Katherine M. (March 27, 2012). "Cucurbita spp. and Lagenaria siceraria (Molina) - Standley Squash, Gourd, and Pumpkin; Bottle Gourd: Cucurbitaceae". Washington University in St. Louis. Retrieved December 31, 2014.

- ↑ Roush, Wade (9 May 1997). "Archaeobiology: Squash Seeds Yield New View of Early American Farming". Science. American Association For the Advancement of Science. 276 (5314): 894–895. doi:10.1126/science.276.5314.894.

- ↑ Schoenwetter, James (April 1974). "Pollen Records of Guila Naquitz Cave". American Antiquity. Society for American Archaeology. 39 (2): 292–303. doi:10.2307/279589. JSTOR 279589.

- ↑ Benz, Bruce F. (2005). "Archaeological Evidence of Teosinte Domestication From Guilá Naquitz, Oaxaca". Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences. 98 (4): 2104–2106. doi:10.1073/pnas.98.4.2104.

- ↑ Smith, Bruce D. (22 December 1989). "Origins of Agriculture in Eastern North America". Science. Washington, DC. 246 (4937): 1566–1571. doi:10.1126/science.246.4937.1566. PMID 17834420.

- ↑ Smith, Bruce D. (May 1997). "The Initial Domestication of Cucurbita pepo in the Americas 10,000 Years Ago". Science. Washington, DC. 276: 932–934. doi:10.1126/science.276.5314.932.

- ↑ Feinman, Gary M.; Manzanilla, Linda (2000). Cultural Evolution: Contemporary Viewpoints. New York: Kluwer Academic. p. 31. ISBN 978-0-306-46240-5.

- ↑ Landon, Amanda J. (2008). "The "How" of the Three Sisters: The Origins of Agriculture in Mesoamerica and the Human Niche". Nebraska Anthropologist. Lincoln, NE: University of Nebraska-Lincoln: 110–124.

- ↑ Bushnell, G. H. S. (1976). "The Beginning and Growth of Agriculture in Mexico". Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society of London. London. 275 (936): 117–120. doi:10.1098/rstb.1976.0074.

- ↑ "How Did the Squash Get its Name?". Library of Congress. Retrieved October 10, 2013.

- ↑ Cutler, Charles L. (2000). O Brave New Words: Native American Loanwords in Current English. Norman, OK: University of Oklahoma Press. pp. 39–42. ISBN 978-0-8061-3246-4.

- 1 2 Chen, Jian Chao; Chiu, Ming Hua; Nie, Rui Lin; Cordell, Geoffrey A.; Qui, Samuel X. (2005). "Cucurbitacins and Cucurbitane Glycosides: Structures and Biological Activities". Natural Product Reports. 22 (5): 386–399. doi:10.1039/B418841C. PMID 16010347.

- ↑ Glover, Tony. "Bitter Cucumbers and Squash" (PDF). Alabama Cooperative Extension System. Retrieved November 23, 2014.

- ↑ Lim, Tong Kwee (2012). Edible Medicinal And Non-Medicinal Plants: Volume 2, Fruits. New York: Springer. p. 283. ISBN 978-94-007-1763-3.

- ↑ Lazos, E. S. (July 1992). "Certain Functional Properties of Defatted Pumpkin Seed Flour". Plant Foods for Human Nutrition. 42 (3): 257–273. doi:10.1007/bf02193934. PMID 1502127.

- 1 2 Geisler, Malinda (May 2012). "Squash". Agricultural Marketing Resource Center, Iowa State University. Retrieved October 13, 2013.

- 1 2 3 4 5 "Pumpkins, Squash, and Gourds". Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations. 2012. Retrieved October 13, 2013.

- ↑ "What's So Great About Winter Squash?" (PDF). University of the District of Columbia. Retrieved January 14, 2015.

- ↑ Mansour, Esam H.; Dworschák, Erno; Lugasi, Andrea; Barna, Barna; Gergely, Anna (1993). "Nutritive Value of Pumpkin (Cucurbita Pepo Kakai 35) Seed Products". Journal of the Science of Food and Agriculture. 61 (1): 73–78. doi:10.1002/jsfa.2740610112.

- ↑ Stevenson DG, Eller FJ, Wang L, Jane JL, Wang T, Inglett GE (2007). "Oil and tocopherol content and composition of pumpkin seed oil in 12 cultivars". J Agric Food Chem. 55 (10): 4005–16. doi:10.1021/jf0706979. PMID 17439238.

- ↑ Durante M, Lenucci MS, Mita G (2014). "Supercritical carbon dioxide extraction of carotenoids from pumpkin (Cucurbita spp.): a review.". Int J Mol Sci. 15 (4): 6725–40. doi:10.3390/ijms15046725. PMC 4013658

. PMID 24756094.

. PMID 24756094. - ↑ Peirce, Andrea (1999). The American Pharmaceutical Association Practical Guide to Natural Medicines. New York: Stonesong Press, William Morrow & Company. pp. 212–214. ISBN 0-688-16151-0.

- ↑ Mihranian, Valentine H.; Abou-Chaar, Charles I. (1968). "Extraction, Detection, and Estimation of Cucurbitin in Cucurbita Seeds". Lloydia. American Society of Pharmacognosy. 31 (1): 23–29.

- ↑ Assessment report on Cucurbita pepo L. (pdf) (Report). Committee on Herbal Medicinal Products (HMPC), European Medicines Agency. 13 September 2011. pp. 25–26. Retrieved 21 November 2015.

- 1 2 Preedy, Victor R.; Watson, Ronald Ross; Patel, Vinwood B. (2011). Nuts and Seeds in Health and Disease Prevention. London: Academic Press. p. 936. ISBN 978-0-12-375688-6.

- ↑ Barbieri, L.; Polito, L.; Bolognesi, A.; Ciani, M.; Pelosi, E.; Farini, V.; Jha, A. K.; Sharma, N.; Vivanco, J. M.; Chambery, A.; Parente, A.; Stirpe, F. (May 2006). "Ribosome-inactivating Proteins in Edible Plants and Purification and Characterization of a New Ribosome-inactivating Protein From Cucurbita moschata". Biochimica et Biophysica Acta. 1760 (5): 783–792. doi:10.1016/j.bbagen.2006.01.002. PMID 16564632.

- ↑ Hou, Xiaomin; Meeha n, Edward J.; Xie, Jieming; Huang, Mingdong; Chen, Minghuang; Chen, Liqing (October 2008). "Atomic Resolution Structure of Cucurmosin, a Novel Type 1 ribosome-inactivating Protein From the Sarcocarp of Cucurbita moschata". Journal of Structural Biology. 164 (1): 81–87. doi:10.1016/j.jsb.2008.06.011.

- 1 2 Tallamy, Douglas W.; Krischik, Vera A. (1989). "Variation and Function of Cucurbitacins in Cucurbita: An Examination of Current Hypotheses". The American Naturalist. The University of Chicago Press. 133 (6): 766–786. doi:10.1086/284952. JSTOR 2462036.

- 1 2 Vidal, S., ed. (2005). "4". Western Corn Rootworm: Ecology and Management (PDF). Wallingford, UK: CAB International. pp. 67–71. doi:10.1079/9780851998176.0000. ISBN 0-85199-817-8.

- ↑ Merrick, Laura C. "Natural Hybridization of Wild Cucurbita sororia Group and Domesticated C. mixta in Southern Sonora, Mexico". North Carolina State University. Retrieved November 24, 2014.

- ↑ "Pumpkin". Drugs.com. 2009. Retrieved September 1, 2013.

- ↑ McAuslane, Heather J.; Webb, Susan E.; Elmstrom, Gary W. (June 1996). "Resistance in Germplasm of Cucurbita pepo to Silverleaf, a Disorder Associated with Bemisia argentifolii (Homoptera: Aleyrodidae)". The Florida Entomologist. Lutz, FL: Florida Entomological Society. 79 (2): 206–221. doi:10.2307/3495818. JSTOR 3495818.

- 1 2 "Vegetable Pumpkin". University of Illinois Extension. Retrieved October 20, 2013.

- ↑ "Common Name: Squash Bug". University of Florida. Retrieved October 26, 2013.

- ↑ "Pumpkin beetle". Pests of Cucurbits. IndiaAgroNet.com. Retrieved 20 May 2016.

- 1 2 "Mosaic Diseases of Cucurbits" (PDF). University of Illinois. Retrieved October 26, 2013.

- 1 2 "Virus Diseases of Cucurbit Crops" (PDF). Department of Agriculture, Government of Western Australia. Retrieved December 31, 2014.

- ↑ Roossinck, Marilyn J.; Palukaitis, Peter (1990). "Rapid Induction and Severity of Symptoms in Zucchini Squash (Cucurbita pepo) Map to RNA 1 of Cucumber Mosaic Virus" (PDF). Molecular Plant-Microbe Interactions. 3 (3): 188–192. doi:10.1094/mpmi-3-188.

- ↑ Havelda, Zoltan; Maule, Andrew J. (October 2000). "Complex Spatial Responses to Cucumber Mosaic Virus Infection in Susceptible Cucurbita pepo Cotyledons". Plant Cell. 12 (10): 1975–1986. doi:10.1105/tpc.12.10.1975. PMC 149134

. PMID 11041891.

. PMID 11041891. - ↑ "Virus Diseases of Cucurbits". Cornell University. October 1984. Retrieved October 26, 2013.

- ↑ Provvidenti, R.; Gonsalves, D. (May 1984). "Occurrence of Zucchini Yellow Mosaic Virus in Cucurbits from Connecticut, New York, Florida, and California" (PDF). Plant Disease. pp. 443–446. doi:10.1094/pd-69-443. ISSN 0191-2917.

- ↑ "Squash". Texas A&M University. Retrieved October 26, 2013.

- ↑ Salama, El-Sayed A.; Sill Jr., W. H. (1968). "Resistance to Kansas Squash Mosaic Virus Strains Among Cucurbita Species". Transactions of the Kansas Academy of Science. 71 (1): 62–68. doi:10.2307/3627399. JSTOR 3627399.

- 1 2 "Moche Decorated Ceramics". Metropolitan Museum of Art. Retrieved October 10, 2013.

- ↑ Benson, Elizabeth P. (1983). "A Moche "Spatula"". Metropolitan Museum Journal. The University of Chicago Press. 18: 39–52. doi:10.2307/1512797. JSTOR 1512797.

- ↑ Berrin Larco Museum, Katherine (1997). The Spirit of Ancient Peru: Treasures from the Museo Arqueológico Rafael Larco Herrera. New York: Thames and Hudson. ISBN 978-0-500-01802-6.

- ↑ Whitaker, Thomas W. (1947). "American Origin of Cultivated Cucurbits". Annals of the Missouri Botanical Garden. St. Louis, MO: Missouri Botanical Garden Press. 34: 101–111. doi:10.2307/2394459. JSTOR 2394459.

- ↑ Whitaker, Thomas W. (1956). "The Origin of the Cultivated Cucurbita". The American Naturalist. Chicago, IL: University of Chicago Press. 90 (852): 171–176. doi:10.1086/281923. JSTOR 2458406.

- ↑ Janick, Jules; Paris, Harry S. (February 2006). "The Cucurbit Images (1515–1518) of the Villa Farnesina, Rome". Annals of Botany. 97 (2): 165–176. doi:10.1093/aob/mcj025. PMC 2803371

. PMID 16314340.

. PMID 16314340. - ↑ Paris, Harry S.; Daunay, Marie-Christine; Pitrat, Michel; Janick, Jules (July 2006). "First Known Image of Cucurbita in Europe, 1503–1508". Annals of Botany. 98 (1): 41–47. doi:10.1093/aob/mcl082. PMC 2803533

. PMID 16687431.

. PMID 16687431. - ↑ "The Marrow Song (Oh What A Beauty!) by Edrich Siebert". Songfacts. Retrieved November 20, 2014.

- ↑ "The Marrow Song". The Wurzels. Retrieved November 20, 2014.

- ↑ "The Wurzels: Cutler of the West". Last.fm. Retrieved November 20, 2014.

- ↑ "The Pumpkin". Poets.org. Retrieved November 20, 2014.

- ↑ Cavna, Michael (October 27, 2011). "'It's the Great Pumpkin, Charlie Brown': 7 Things You Don't Know About Tonight's 'Peanuts' Special". Washington Post. Retrieved November 20, 2014.

- ↑ Cutler, H.C.; Whitaker, T.W. (1961). "History and Distribution of the Cultivated Cucurbits in the Americas". American Antiquity. 26 (4): 469–485. doi:10.2307/278735. JSTOR 278735.(subscription required)

- ↑ Robert E. Henshaw, ed. (2011). Environmental History of the Hudson River. Albany, NY: State University of New York Press. ISBN 978-1-4384-4026-2.

- ↑ Volker Schulz, ed. (2004). Rational Phytotherapy: A Reference Guide for Physicians and Pharmacists (5th ed.). Munich: Springer. pp. 304–305. ISBN 978-3-540-40832-1.

- ↑ "Pumpkin seed (Cucurbitae peponis semen)". Heilpflanzen-Welt Bibliothek. Retrieved March 25, 2015.

- ↑ Foster, Steven; Tyler, Varro E. (1999). Tyler's Honest Herbal: A Sensible Guide to the Use of Herbs and Related Remedies (4th ed.). Binghamton, NY: Routledge. pp. 131–132.

- ↑ Xiao, S. H.; Keiser, J.; Chen, M. G.; Tanner, M.; Utzinger, J. (2010). "Research and Development of Antischistosomal Drugs in the People's Republic of China a 60-year review". Advances in Parasitology. 73: 231–295. doi:10.1016/S0065-308X(10)73009-8. PMID 20627145.

- ↑ Wu, Yan; Fischer, Warren (1997). Practical Therapeutics of Traditional Chinese Medicine. Taos, NM: Paradigm Publications. pp. 282–283. ISBN 978-0-912111-39-1.

- ↑ Andrade-Cetto, A.; Heinrich, M. (July 2005). "Mexican Plants With Hypoglycaemic Effect Used in the Treatment of Diabetes". Journal of Ethnopharmacology. 99 (3): 325–348. doi:10.1016/j.jep.2005.04.019. PMID 15964161.

- ↑ Richardson, R. W. "Squash and Pumpkin" (PDF). United States Department of Agriculture, Agricultural Research Service, National Plant Germplasm System. Retrieved September 2, 2013.

- ↑ "Spiced Pumpkin Butter". Better Homes and Gardens. Retrieved January 12, 2014.

- ↑ Lynch, Rene (October 1, 2013). "Pumpkin Bread and 18 Other Pumpkin Recipes You Must Make Now". Los Angeles Times. Retrieved October 8, 2013.

- ↑ Garratt, N. (2013). Mango and Mint: Arabian, Indian, and North African Inspired Vegan Cuisine. Tofu Hound Press. PM Press. p. 46. ISBN 978-1-60486-323-9.

- ↑ Bemis, W. P. (1978). "The Versatility of the Feral Buffalo Gourd, Cucurbita foetidissima HBK". Cucurbit Genetics Cooperative Report. 1: 25.

- ↑ Jaffrey, Madhur (1982). Madhur Jaffrey's Indian Cookery. London: BBC Books. p. 90. ISBN 0-563-16491-3.

- ↑ David, Elizabeth (1987) [1951]. French Country Cooking. London: Dorling Kindersley. p. 179. ISBN 0-86318-251-8.

- ↑ della Salda, Anna Gosetti (1993) [1967]. Le Ricette Regionali Italiane (in Italian). Solares. pp. 107, 439, 878, 987.

- ↑ Yoneda, Soei (1987) [1982]. The Heart of Zen Cuisine. New York: Kodansha America. pp. 131, 133, 154. ISBN 0-87011-848-X.

- ↑ "Sabores de Bolivia" (in Spanish). Cristina Olmos. Retrieved November 22, 2014.

- ↑ McMurray, Jenna (October 11, 2014). "Smashing Success! Crowd Watches as Pumpkin Dropped on Old Car ... All for a Gourd Cause". Calgary Sun. Retrieved November 20, 2014.

- ↑ "Events". Tourist Board of Ivanić-Grad. Retrieved 3 February 2016.

- ↑ "Caligny: le Village de l'Orne où le Potiron est Roi" (in French). info.fr. Retrieved December 31, 2014.

- ↑ "Fête de la Citrouille et des Cucurbitacées de Saint Laurent" (in French). France Bleu. Retrieved November 22, 2014.

- ↑ "Festa della Zucca" (in Italian). Associazione Pro Loco di Venzone. Retrieved November 22, 2014.

- ↑ "21º Festa della Zucca SALZANO" (in Italian). Pro Loco Salzano. Retrieved November 22, 2014.

- ↑ "Tra Meno un Mese Torna la Fiera Regionale della Zucca di Piozzo, ecco il Programma Ufficiale della 21esima Edizione" (in Italian). Pro Loco di Piozzo. Retrieved November 22, 2014.

- ↑ "Fiesta de la Calabaza en Gavirate (Varese)" (in Spanish). SarayT. Retrieved November 22, 2014.

- ↑ "Autumn Events Calendar". Asahikawa Tourism. Retrieved November 20, 2014.

- ↑ "Festival del Zapallo y de la Trucha de Curibaya se Realizará en la Plaza Quiñonez" (in Spanish). Radio Uno. Retrieved November 22, 2014.

- ↑ "Festivals and Events in Switzerland". Travelsignposts. Retrieved November 22, 2014.

- ↑ "Fiesta Nacional del Zapallo" (in Spanish). La Fiesta Nacional. Retrieved November 22, 2014.

- ↑ "Esperanza: Rocío Damiano fue elegida Reina Nacional del Zapallo en Ceres" (in Spanish). Ente Cultura. Retrieved November 22, 2014.

- ↑ "Ceres: Presentaron la Fiesta Nacional del Zapallo" (in Spanish). El Litoral. Retrieved November 22, 2014.

- ↑ "Presentacion Oficial – 43º Fiesta Nacional del Zapallo" (in Spanish). Ceres Online. Retrieved November 22, 2014.

- ↑ "Festival da Abóbora de Lourinhã e Atalaia" (in Portuguese). Festival da Abobora. Retrieved November 22, 2014.

- ↑ "The World's Largest Pumpkin Festival in Germany". USA Today. Retrieved November 20, 2014.

- ↑ "Giant Vegetables from UK Festival". CBS News. Retrieved November 20, 2014.

- ↑ "Punkin Chunkin". Science Channel. Retrieved November 20, 2014.

- ↑ Campbell, Andy (November 26, 2013). "Punkin Chunkin 2013: Will Someone Finally Launch A Pumpkin One Mile?". Huffington Post. Retrieved November 20, 2014.

- ↑ Dandrea, Alyssa (October 20, 2013). "Smiles, Pumpkins Abound as Keene Breaks Jack-o'-lantern Record". The Keene Sentinel. Retrieved November 20, 2013.

- ↑ "History of the Jack O' Lantern". History.com. A&E Networks. Retrieved November 20, 2014.

- ↑ Stephens, James M. "Pumpkin — Cucurbita spp.". University of Florida. Retrieved November 23, 2014.

- ↑ Baggett, J. R. "Attempts to Cross Cucurbita moschata (Duch.) Poir. 'Butternut' and C. pepo L. 'Delicata'". North Carolina State University. Retrieved November 23, 2014.

- ↑ Richardson, R. W. "Squash and Pumpkin" (PDF). United States Department of Agriculture, Agricultural Research Service, National Plant Germplasm System. Retrieved November 23, 2014.

- ↑ "IncrEdible! Kew Gardens to Unveil Towering Pyramid of Pumpkins in London". Country Life. September 12, 2013. Retrieved November 20, 2014.

External links

-

The dictionary definition of Cucurbita at Wiktionary

The dictionary definition of Cucurbita at Wiktionary -

Media related to Cucurbita at Wikimedia Commons

Media related to Cucurbita at Wikimedia Commons -

Data related to Cucurbita at Wikispecies

Data related to Cucurbita at Wikispecies