Subgroup

| Algebraic structure → Group theory Group theory |

|---|

|

|

Modular groups

|

Infinite dimensional Lie group

|

In group theory, a branch of mathematics, given a group G under a binary operation ∗, a subset H of G is called a subgroup of G if H also forms a group under the operation ∗. More precisely, H is a subgroup of G if the restriction of ∗ to H × H is a group operation on H. This is usually denoted H ≤ G, read as "H is a subgroup of G".

The trivial subgroup of any group is the subgroup {e} consisting of just the identity element.

A proper subgroup of a group G is a subgroup H which is a proper subset of G (i.e. H ≠ G). This is usually represented notationally by H < G, read as "H is a proper subgroup of G". Some authors also exclude the trivial group from being proper (i.e. {e} ≠ H ≠ G).[1][2]

If H is a subgroup of G, then G is sometimes called an overgroup of H.

The same definitions apply more generally when G is an arbitrary semigroup, but this article will only deal with subgroups of groups. The group G is sometimes denoted by the ordered pair (G, ∗), usually to emphasize the operation ∗ when G carries multiple algebraic or other structures.

This article will write ab for a ∗ b, as is usual.

Basic properties of subgroups

- A subset H of the group G is a subgroup of G if and only if it is nonempty and closed under products and inverses. (The closure conditions mean the following: whenever a and b are in H, then ab and a−1 are also in H. These two conditions can be combined into one equivalent condition: whenever a and b are in H, then ab−1 is also in H.) In the case that H is finite, then H is a subgroup if and only if H is closed under products. (In this case, every element a of H generates a finite cyclic subgroup of H, and the inverse of a is then a−1 = an − 1, where n is the order of a.)

- The above condition can be stated in terms of a homomorphism; that is, H is a subgroup of a group G if and only if H is a subset of G and there is an inclusion homomorphism (i.e., i(a) = a for every a) from H to G.

- The identity of a subgroup is the identity of the group: if G is a group with identity eG, and H is a subgroup of G with identity eH, then eH = eG.

- The inverse of an element in a subgroup is the inverse of the element in the group: if H is a subgroup of a group G, and a and b are elements of H such that ab = ba = eH, then ab = ba = eG.

- The intersection of subgroups A and B is again a subgroup.[3] The union of subgroups A and B is a subgroup if and only if either A or B contains the other, since for example 2 and 3 are in the union of 2Z and 3Z but their sum 5 is not. Another example is the union of the x-axis and the y-axis in the plane (with the addition operation); each of these objects is a subgroup but their union is not. This also serves as an example of two subgroups, whose intersection is precisely the identity.

- If S is a subset of G, then there exists a minimum subgroup containing S, which can be found by taking the intersection of all of subgroups containing S; it is denoted by <S> and is said to be the subgroup generated by S. An element of G is in <S> if and only if it is a finite product of elements of S and their inverses.

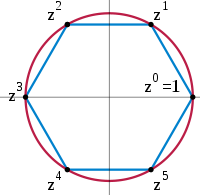

- Every element a of a group G generates the cyclic subgroup <a>. If <a> is isomorphic to Z/nZ for some positive integer n, then n is the smallest positive integer for which an = e, and n is called the order of a. If <a> is isomorphic to Z, then a is said to have infinite order.

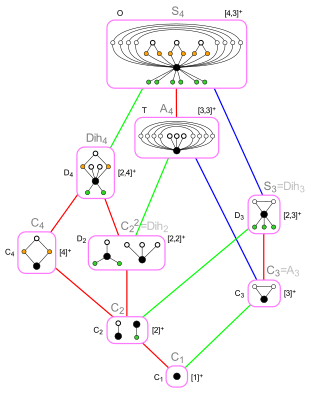

- The subgroups of any given group form a complete lattice under inclusion, called the lattice of subgroups. (While the infimum here is the usual set-theoretic intersection, the supremum of a set of subgroups is the subgroup generated by the set-theoretic union of the subgroups, not the set-theoretic union itself.) If e is the identity of G, then the trivial group {e} is the minimum subgroup of G, while the maximum subgroup is the group G itself.

Cosets and Lagrange's theorem

Given a subgroup H and some a in G, we define the left coset aH = {ah : h in H}. Because a is invertible, the map φ : H → aH given by φ(h) = ah is a bijection. Furthermore, every element of G is contained in precisely one left coset of H; the left cosets are the equivalence classes corresponding to the equivalence relation a1 ~ a2 if and only if a1−1a2 is in H. The number of left cosets of H is called the index of H in G and is denoted by [G : H].

Lagrange's theorem states that for a finite group G and a subgroup H,

where |G| and |H| denote the orders of G and H, respectively. In particular, the order of every subgroup of G (and the order of every element of G) must be a divisor of |G|.

Right cosets are defined analogously: Ha = {ha : h in H}. They are also the equivalence classes for a suitable equivalence relation and their number is equal to [G : H].

If aH = Ha for every a in G, then H is said to be a normal subgroup. Every subgroup of index 2 is normal: the left cosets, and also the right cosets, are simply the subgroup and its complement. More generally, if p is the lowest prime dividing the order of a finite group G, then any subgroup of index p (if such exists) is normal.

Example: Subgroups of Z8

Let G be the cyclic group Z8 whose elements are

and whose group operation is addition modulo eight. Its Cayley table is

| + | 0 | 2 | 4 | 6 | 1 | 3 | 5 | 7 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 0 | 0 | 2 | 4 | 6 | 1 | 3 | 5 | 7 |

| 2 | 2 | 4 | 6 | 0 | 3 | 5 | 7 | 1 |

| 4 | 4 | 6 | 0 | 2 | 5 | 7 | 1 | 3 |

| 6 | 6 | 0 | 2 | 4 | 7 | 1 | 3 | 5 |

| 1 | 1 | 3 | 5 | 7 | 2 | 4 | 6 | 0 |

| 3 | 3 | 5 | 7 | 1 | 4 | 6 | 0 | 2 |

| 5 | 5 | 7 | 1 | 3 | 6 | 0 | 2 | 4 |

| 7 | 7 | 1 | 3 | 5 | 0 | 2 | 4 | 6 |

This group has two nontrivial subgroups: J={0,4} and H={0,2,4,6}, where J is also a subgroup of H. The Cayley table for H is the top-left quadrant of the Cayley table for G. The group G is cyclic, and so are its subgroups. In general, subgroups of cyclic groups are also cyclic.

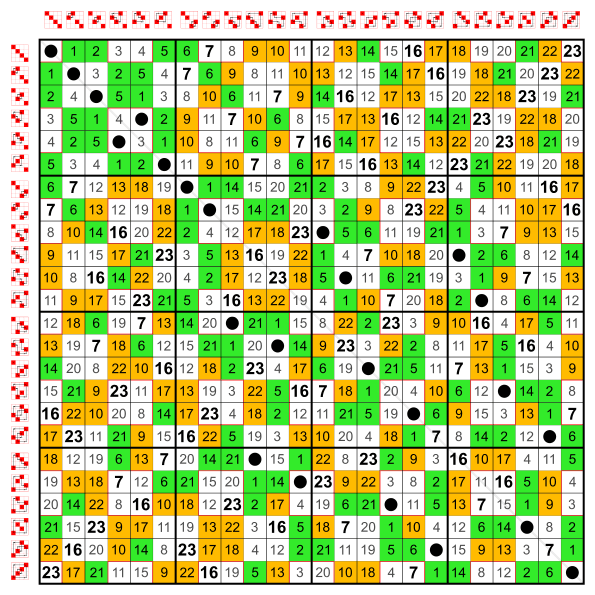

Example: Subgroups of S4 (the symmetric group on 4 elements)

Every group has as many small subgroups as neutral elements on the main diagonal:

The trivial group and two-element groups Z2. These small subgroups are not counted in the following list.

The symmetric group S4 showing all permutations of 4 elements |

|

12 elements

8 elements

%3B_subgroup_of_S4.svg.png) | %3B_subgroup_of_S4.svg.png) Dihedral group of order 8 Subgroups: .svg.png) .svg.png) %3B_subgroup_of_S4.svg.png) | %3B_subgroup_of_S4.svg.png) Dihedral group of order 8 Subgroups: .svg.png) .svg.png) %3B_subgroup_of_S4.svg.png) |

6 elements

.svg.png) | .svg.png) Symmetric group S3 Subgroup: .svg.png) | .svg.png) Symmetric group S3 Subgroup: .svg.png) | .svg.png) Symmetric group S3 Subgroup: .svg.png) |

4 elements

.svg.png) Klein four-group | .svg.png) Klein four-group | .svg.png) Klein four-group |

%3B_subgroup_of_S4.svg.png) Cyclic group Z4 | %3B_subgroup_of_S4.svg.png) Cyclic group Z4 | %3B_subgroup_of_S4.svg.png) Cyclic group Z4 |

3 elements

.svg.png) Cyclic group Z3 | .svg.png) Cyclic group Z3 | .svg.png) Cyclic group Z3 |

.svg.png) Cyclic group Z3 |

Other examples

- An ideal in a ring is a subgroup of the additive group of .

- Let be an abelian group; the elements of that have finite period form a subgroup of called the torsion subgroup of .

See also

Notes

References

- Jacobson, Nathan (2009), Basic algebra, 1 (2nd ed.), Dover, ISBN 978-0-486-47189-1.

- Hungerford, Thomas (1974), Algebra (1st ed.), Springer-Verlag, ISBN 9780387905181.

- Artin, Michael (2011), Algebra (2nd ed.), Prentice Hall, ISBN 9780132413770.

.svg.png)