Divisor

In mathematics, a divisor of an integer , also called a factor of , is an integer that can be multiplied by some other integer to produce . An integer is divisible by another integer if is a factor of , so that dividing by leaves no remainder.

Definition

Two versions of the definition of a divisor are commonplace:

- For integers and , it is said that divides , is a divisor of , or is a multiple of , and this is written as

- if there exists an integer such that .[1] Under this definition, the statement holds for every .

- As before, but with the additional constraint .[2] Under this definition, the statement does not hold for .

In the remainder of this article, which definition is applied is indicated where this is significant.

General

Divisors can be negative as well as positive, although sometimes the term is restricted to positive divisors. For example, there are six divisors of 4; they are 1, 2, 4, −1, −2, and −4, but only the positive ones (1, 2, and 4) would usually be mentioned.

1 and −1 divide (are divisors of) every integer. Every integer (and its negation) is a divisor of itself.[3] Every integer is a divisor of 0.[4] Integers divisible by 2 are called even, and numbers not divisible by 2 are called odd.

1, −1, n and −n are known as the trivial divisors of n. A divisor of n that is not a trivial divisor is known as a non-trivial divisor. A non-zero integer with at least one non-trivial divisor is known as a composite number, while the units −1 and 1 and prime numbers have no non-trivial divisors.

There are divisibility rules which allow one to recognize certain divisors of a number from the number's digits.

The generalization can be said to be the concept of divisibility in any integral domain.

Examples

- 7 is a divisor of 42 because , so we can say . It can also be said that 42 is divisible by 7, 42 is a multiple of 7, 7 divides 42, or 7 is a factor of 42.

- The non-trivial divisors of 6 are 2, −2, 3, −3.

- The positive divisors of 42 are 1, 2, 3, 6, 7, 14, 21, 42.

- , because .

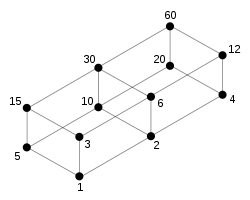

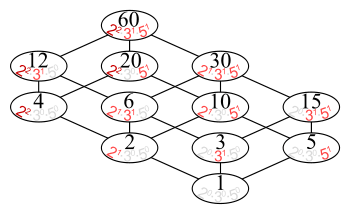

- The set of all positive divisors of 60, , partially ordered by divisibility, has the Hasse diagram:

Further notions and facts

There are some elementary rules:

- If and , then , i.e. divisibility is a transitive relation.

- If and , then or .

- If and , then holds, as does .[5] However, if and , then does not always hold (e.g. and but 5 does not divide 6).

If , and gcd, then . This is called Euclid's lemma.

If is a prime number and then or .

A positive divisor of which is different from is called a proper divisor or an aliquot part of . A number that does not evenly divide but leaves a remainder is called an aliquant part of .

An integer whose only proper divisor is 1 is called a prime number. Equivalently, a prime number is a positive integer which has exactly two positive factors: 1 and itself.

Any positive divisor of is a product of prime divisors of raised to some power. This is a consequence of the fundamental theorem of arithmetic.

A number is said to be perfect if it equals the sum of its proper divisors, deficient if the sum of its proper divisors is less than , and abundant if this sum exceeds .

The total number of positive divisors of is a multiplicative function , meaning that when two numbers and are relatively prime, then . For instance, ; the eight divisors of 42 are 1, 2, 3, 6, 7, 14, 21 and 42. However the number of positive divisors is not a totally multiplicative function: if the two numbers and share a common divisor, then it might not be true that . The sum of the positive divisors of is another multiplicative function (e.g. ). Both of these functions are examples of divisor functions.

If the prime factorization of is given by

then the number of positive divisors of is

and each of the divisors has the form

where for each

For every natural , .

Also,[6]

where is Euler–Mascheroni constant. One interpretation of this result is that a randomly chosen positive integer n has an expected number of divisors of about .

In abstract algebra

Given the definition for which holds, the relation of divisibility turns the set of non-negative integers into a partially ordered set: a complete distributive lattice. The largest element of this lattice is 0 and the smallest is 1. The meet operation ∧ is given by the greatest common divisor and the join operation ∨ by the least common multiple. This lattice is isomorphic to the dual of the lattice of subgroups of the infinite cyclic group .

See also

- Arithmetic functions

- Divisibility rule

- Divisor function

- Euclid's algorithm

- Fraction (mathematics)

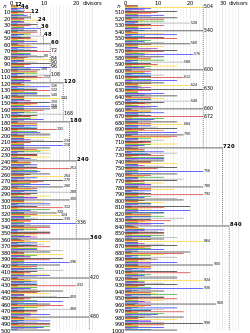

- Table of divisors — A table of prime and non-prime divisors for 1–1000

- Table of prime factors — A table of prime factors for 1–1000

- Unitary divisor

Notes

- ↑ for instance, Sims 1984, p. 42 or Durbin 1992, p. 61

- ↑ Herstein 1986, p. 26

- ↑ This statement either requires 0|0 or needs to be restricted to nonzero integers.

- ↑ This statement either requires 0|0 or needs to be restricted to nonzero integers.

- ↑ . Similarly,

- ↑ Hardy, G. H.; Wright, E. M. (April 17, 1980). An Introduction to the Theory of Numbers. Oxford University Press. p. 264. ISBN 0-19-853171-0.

References

- Durbin, John R. (1992). Modern Algebra: An Introduction (3rd ed.). New York: Wiley. ISBN 0-471-51001-7.

- Richard K. Guy, Unsolved Problems in Number Theory (3rd ed), Springer Verlag, 2004 ISBN 0-387-20860-7; section B.

- Herstein, I. N. (1986), Abstract Algebra, New York: Macmillan Publishing Company, ISBN 0-02-353820-1

- Øystein Ore, Number Theory and its History, McGraw–Hill, NY, 1944 (and Dover reprints).

- Sims, Charles C. (1984), Abstract Algebra: A Computational Approach, New York: John Wiley & Sons, ISBN 0-471-09846-9