Suicide in South Korea

| Suicide |

|---|

|

|

Related phenomena |

Suicide in South Korea is a serious and widespread problem, with the country having the second-highest suicide rate in the world according to the World Health Organization, as well as the highest suicide rate for an OECD member state.[1][2]

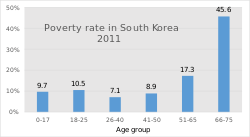

One reason for its high suicide rate compared to other countries in the developed world is a large amount of suicide among the elderly. The prevalence of suicide among elderly South Koreans is due to the amount of widespread poverty among senior citizens in South Korea, with nearly half of the country's elderly population living below the poverty line. Combined with a poorly-funded social safety net for the elderly, this results in them killing themselves not to be a financial burden on their families, since the old social structure where children looked after their parents has largely disappeared in the 21st century.[3][4] As a result, people living in rural areas tend to have higher suicide rates.

However, proactive government efforts to decrease the rate has shown effectiveness in 2014, when there were 27.3 suicides per 100,000 people, a 4.1% decline from the previous year (28.5 people) and the lowest in 6 years since 2008's 26.0 people.[5][6]

Statistics

Age

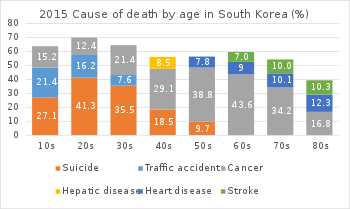

One of the reasons of South Korea's relatively high suicide rate is due to the elderly's substantially high suicide rate. This is due to poor elderly people killing themselves not to be a burden on their families, since there is a poorly-funded welfare system,[3] and the old social structure where children looked after their parents, has largely disappeared in the 21st century.[4] As a result, people living in rural areas have higher suicide rates.

Although very low compared to other age groups, school students and college students have a higher suicide rate.[7]

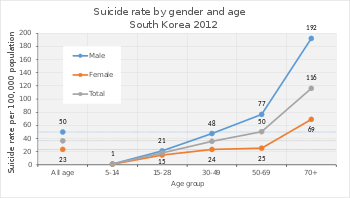

Gender

On average, men have a suicide rate that is twice as high as women.[6] However, the suicide attempt rate is higher for women than men.[8] According to a study, because men use more severe and lethal suicide methods, men have higher suicidal completion rate than women. The Risk-Rescue Rating Scale (RRRS), which measures the lethality of the suicidal method by gauging the ratio between five risk and five rescue factors, averaged out to be 37.18 for men and 34.00 for women.[9] One study has translated this to the fact that women attempt to commit suicide more as a demonstration, while men commit suicide with a determined purpose.[10]

Compared to other OECD countries, South Korea’s female suicide rate marks the first with 15.0 deaths on the suicidal rate list per 100,000 deaths, while the male suicide rate marks third with 32.5 per every 100,000 deaths.[11] Women also had a higher increase of proportional suicide rate over men between 1986 and 2005. Men increased by 244%, while women increased by 282%.[11]

Socioeconomic status

Socioeconomic status is measured by a population’s level of education, degree of urbanity and deprivation of the residence.[12] The reason many adolescence have suicidal tendencies are due to low socioeconomic status, high stress, inadequate sleep, alcohol use, and smoking.[13] The economic hardship factor is noted as the most frequently referred cause for elderly suicides. As 71.4% of the elderly population is uneducated and 37.1% of them live in rural areas, they are more likely to face economic hardship, which can lead to health problems and family conflicts.[12] All these factors together lead to an increase in suicidal ideation and completion.[12]

Regions

Gangwon has the highest suicide rate compared with any other geographic region in South Korea by 37.84%.[14] Following Gangwon, Chungnam rates second and Jeonbuk rates third.[14] Ulsan, Gangwon, and Incheon have the highest suicide rate for the elders, people of age above 65.[14] Daegu has the highest suicide rate for age ranging from 40 to 59.[14] Finally, Gangwon, Jeonnam, and Chungnam have highest suicide rate for age of 20-39.[14]

Methods

Because South Korean law heavily restricts firearms possession, only one third of South Korean women use violent methods to commit suicide. Poisoning is the most commonly used method, as half of South Korean women who commit suicide use pesticides.[15] 58.3% of suicides from 1996 to 2005 used pesticide poisoning.[16] Another prevalent method that people use is hanging.[17] Just as women prefer certain suicide methods, a study has shown that unplanned suicide attempters use certain suicide methods more than planned suicide attempters. Unplanned suicide attempters tend to use chemical agents or falling three times more than planned suicide attempters.[18]

Notable cases

In 2005 actress Lee Eun-ju, the star of hit films including Taegukgi and The Scarlet Letter, committed suicide at age 24.[19] Former President Roh Moo-hyun committed suicide on 23 May 2009 by jumping from a mountain cliff. Supermodel[20] Daul Kim committed suicide on November 19, 2009 in Paris.[21]

Construction tycoon Sung Wan-jong committed suicide in April 2015 amid allegations of corruption and left a suicide note in which he named those whom he claimed had been involved in corruption.[22] Performance artist U;Nee died by hanging in 2007 aged 25.[23] "The Nation's Actress" Choi Jin-sil committed suicide in 2008,[24] as did her ex-husband Cho Sung-min in 2013.

There have also been notable cases of suicides in response to tragedies. Two days after the disaster of the ferry Sewol in April 2014, a high school principal who was rescued committed suicide. He had organized the trip for the students. The president of the ferry company was also later found dead in a suspected suicide. In October 2014, a government safety official committed suicide after 16 people were killed at a concert he oversaw.[25] In 2015, following a fatal bus crash of South Korean civil servants visiting China, a government official involved with the organization committed suicide by jumping out of his hotel room in China.

Causes

Media

According to a study, South Korea experiences a surge of suicides after deaths of celebrities.[26] The study has found three out of eleven cases of celebrity suicide resulted in a higher suicide rate of the population.[26] The study controlled for the potential effects of confounding factors, such as seasonality and unemployment rates, and yet celebrity suicides still had a strong correlation to increased rate of suicide rates for nine weeks.[26] The degree of media coverage of celebrity suicides impacts the degree of increase of suicide rates. In the study, the three celebrity suicides that received wide media coverage led to a surge in suicide rates, and the other celebrity suicides with low media coverage did not lead to an increase in suicide rate.[26] In addition to the increased suicidal ideation, celebrity suicides lead people to use the same methods to commit suicide.[27] Following actress Lee Eun-ju's death in 2005, more people used the same method of hanging.[27]

An ongoing study has also suggested that high use of the Internet may cause suicides.[28] Among 1573 high school students, 1.6% of the population suffered from Internet addiction and 38.0% had a risk of Internet addiction.[28] The students with, or at risk of, internet addiction had a higher rate of suicidal ideation compared to those without Internet addiction.[28]

Family

Many people have been left orphaned or have lost a parent due to the Korean War. Within a random group of 12,532 adults, 18.6% of the respondents have lost their biological parent(s), with maternal death having a bigger impact to the rate of suicidal attempt than paternal death.[29] A study has shown that men have highest suicidal attempt rate when they experience maternal death in the ages of 0-4 and 5-9. Women have the highest suicide attempt rate when they experience maternal death in the ages of 5-9.[29]

Economy

In 1997 and 1998, the 1997 Asian financial crisis hit South Korea.[30] During and after the economic recession of 1998, South Korea experienced a sharp economic recession of −6.9% and a surge of unemployment rate of 7.0%.[30] A study has shown that this economic downfall had a strong correlation with an increase in suicide rates.[30] Increase in unemployment and higher divorce rate during the economic downturn lead to clinical depression, which is a common factor that leads to suicide.[30] Moreover, according to Durkheim, economic downfall disturbs the social standing of an individual, meaning that the individual's demands and expectations no longer be meet. Thus, a person who cannot readjust to the deprived social order caused by economic downfall is more likely to commit suicide.[30]

Analyzing the suicides up to 2003, Park and Lester[31] note that unemployment is a major factor of high suicide rate. In South Korea, it has been the traditional duty of children to take care of their parents.[31] However, as "cultural tradition of filial obligation is not congruent with the increasingly competitive, specialized labor market of the modern era", the elderly are sacrificing themselves by committing suicide so as to lessen the burden on their children.[31]

Education

In South Korea, every student is obligated to take the College Scholastic Ability Test (CSAT). On this day, underclassmen gather and cheer on their seniors as they enter the school to take their exam. The government has also mandated to forbid planes from flying during this time to make sure there are no distractions to these students.[32]

Education in South Korea is extremely competitive, making it difficult to get into an esteemed university. A South Korean student's school year lasts from March to February. The year divides into two semesters: one from March until July, and another from August to February. The average South Korean high school student also spends roughly 16 hours a day on school and school-related activities. They attend after school programs called hagwons and there are over 100,000 of them throughout South Korea, making them a 20 billion dollar industry.[33] Again, this is because of the competitiveness of acceptance into a good university. Most South Korean test scores are also graded on a curve, leading to more competition. Until 2012, students in South Korea went to school from Monday to Friday, and every odd Saturday. Before 2005, South Korean students went to school every day from Monday to Saturday.

Although South Korean education consistently ranks near the top in international academic assessments such as PISA,[34] the enormous stress and pressure[35] on its students is considered by many to constitute child abuse.[36][37] It has been blamed for high suicide rates in South Korea among those aged 10–19.[38]

Mental illness

In South Korea, mental illness is taboo, even within a family. Over 90% of suicide victims had some kind of mental disorder, but only 15% of them received proper treatment. Over two million people suffer with depression annually in South Korea, but only 15,000 choose to receive regular treatment. Because mental illnesses are looked down upon in Korean society, families often tell victims to get over it or to wait until it gets better.[39] Since there is such a strong negative stigma on the treatment of mental illnesses, many symptoms go unnoticed and can lead to many irrational decisions including suicide.

Public image

In the Korean culture, public image is very important as well. There is a lot of pride in personal appearance which is why South Korea has the highest ratio of procedures per capita. One of every five South Koreans get plastic surgery.[40] Although not directly related to the high suicide rate, the need to look a certain way plays a big part in a Korean's self worth, especially if they feel they can't reach society's standards.

Responses

South Korea has implemented the Strategies to Prevent Suicide (STOPS), a project whose "initiatives aimed at increasing public awareness, improving media reporting of suicide, screening for persons at high risk of suicide, restricting access to means, and improving treatment of suicidally depressed patients". All of these methods strive to increase public awareness and governmental support for suicide prevention. Currently, South Korea and other countries that have implemented this initiative are in the process of evaluating how much influence this initiative has on the suicide rate.[41] The education ministry created a smartphone app to check students' social media posts, messages and web searches for words related to suicide.[42]

Because the media coverage and portrayal of suicide influence the suicide rate, the government has "promulgated national guidelines for reporting on suicide in print media". The national guideline helps the media coverage to focus more on warning signs and possibilities of treatment, rather than factors that lead to the suicide.[41]

Another method that South Korea has implemented is educating gatekeepers.[41] The gatekeeper education primarily consists of knowledge of suicide and dealing with suicidal individuals, and this education is provided to teachers, social workers, volunteers and youth leaders.[41] The South Korean government educates gatekeepers within the at-risk communities, such as female elders or low-income families. To maximize the effect of gatekeepers, the government has also implemented evaluation programs to report the results.[41] Physical measures are also taken to prevent suicide. The government has reduced "access to lethal means of self-harm". As mentioned above in the methods, the government has reduced access to poisoning agents, monoxide from charcoal, and finally train platforms. This helps to decrease the impulsive suicidal behavior.[41]

See also

- Salaryman

- Shame society

- List of countries by suicide rate

- Education in South Korea

- Suicide prevention

- Culture of South Korea

- 1997 Asian financial crisis

- Suicide intervention

References

- ↑ "South Korea still has top OECD suicide rate". Korea Herald. 2015-08-30. Retrieved August 8, 2016.

- ↑ Evans, Stephen (5 November 2015). "Korea's hidden problem: Suicidal defectors". BBC News. United Kingdom of Great Britain and Northern Ireland: British Broadcasting Corporation. Retrieved May 17, 2016.

South Korea consistently has the highest suicide rate of all the 34 industrialized countries in the OECD.

- 1 2 Se-woong Koo, "No Country For Old People" (24 September 2014), Korea Exposé.

- 1 2 Kathy Novak (October 23, 2015). "'Forgotten': South Korea's elderly struggle to get by". CNN. Retrieved August 8, 2016.

- ↑ "지난해 한국 자살률 소폭 감소...여전히 OECD 1위". 2015-09-23.

- 1 2 Kim, Kristen (12 June 2015). "International Journal of Mental Health Systems. 2014, Vol. 8 Issue 1, preceding p1-8. 9p. DOI: 10.1186/1752-4458-8-17. KIM KRISTEN".

- ↑ "International Journal of Mental Health Systems. 2014, Vol. 8 Issue 1,". 12 June 2015.

- ↑ "International Journal of Mental Health Systems. 2014, Vol. 8 Issue 1,". 12 June 2015.

- ↑ Hur, Ji-Won, Bun-Hee Lee, Sung-Woo Lee, Se-Hoon Shim, Sang-Woo Han, and Yong-Ku Kim. "Gender Differences in Suicidal Behavior in Korea." Psychiatry Investigation, 2008, 28.

- ↑ Cheong, Kyu-Seok, Min-Hyeok Choi, Byung-Mann Cho, Tae-Ho Yoon, Chang-Hun Kim, Yu-Mi Kim, and In-Kyung Hwang. "Suicide Rate Differences by Sex, Age, and Urbanicity, and Related Regional Factors in Korea." Journal of Preventive Medicine and Public Health, 2012, 70.

- 1 2 Kwon, Jin-Won, Heeran Chun, and Sung-Il Cho. "A Closer Look at the Increase in Suicide Rates in South Korea from 1986–2005." BMC Public Health, 2009, 72.

- 1 2 3 Kim, Myoung-Hee, Kyunghee Jung-Choi, Hee-Jin Jun, and Ichiro Kawachi. "Socioeconomic Inequalities in Suicidal Ideation, Parasuicides, and Completed Suicides in South Korea."Social Science & Medicine 70, no. 8 (2010): 1254-261.

- ↑ "Lee, Gyu‐Young; Choi, Yun‐Jung; Research in Nursing & Health, Vol 38(4), Aug, 2015 pp. 301-310". 12 June 2015.

- 1 2 3 4 5 Park, E,Hyun, Cl Lee, EJ Lee, and SC Hong. "A Study on Regional Differentials in Death Caused by Suicide in South Korea." Europe PubMed Central, 2007.

- ↑ Chen, Ying-Yeh, Nam-Soo Park, and Tsung-Hsueh Lu. "Suicide Methods Used by Women in Korea, Sweden, Taiwan and the United States." Journal of the Formosan Medical Association 108, no. 6 (2009): 452-59.

- ↑ Lee, Won Jin, Eun Shil Cha, Eun Sook Park, Kyoung Ae Kong, Jun Hyeok Yi, and Mia Son. "Deaths from Pesticide Poisoning in South Korea: Trends over 10 years." International Archives of Occupational and Environmental Health 82, no. 3 (2008): 365-71.

- ↑ Kim, Seong Yi, Myoung-Hee Kim, Ichiro Kawachi, and Youngtae Cho. "Comparative Epidemiology of Suicide in South Korea and Japan: Effects of Age, Gender and Suicide Methods." Crisis: The Journal of Crisis Intervention and Suicide Prevention, 2011, 5-14.

- ↑ Jeon, Hong Jin, Jun-Young Lee, Young Moon Lee, Jin Pyo Hong, Seung-Hee Won, Seong-Jin Cho, Jin-Yeong Kim, Sung Man Chang, Hae Woo Lee, and Maeng Je Cho. "Unplanned versus Planned Suicide Attempters, Precipitants, Methods, and an Association with Mental Disorders in a Korea-based Community Sample." Journal of Affective Disorders 127, no. 1-3 (2010): 274-80.

- ↑ "Grief, Speculation Greet Mysterious Lee Eun-ju Suicide". The Chosun Ilbo. 2005-02-24. Retrieved 2014-04-24.

- ↑ nymag.com Daul Kim accessed 4/21/2015

- ↑ telegraph.co.uk Henry Samuel, Daul Kim found hanged after posting web messages 20 Nov 2009

- ↑ BBC News South Korea in turmoil over corruption scandal Stephen Evans, 4/21/2015

- ↑ Looi, Elizabeth, "Korean singer found hanged", Malaysia Star, January 25, 2007.

- ↑ Yi, Whan-woo (6 January 2013). "Choi Jin-sil tragedy relived". The Korea Times. Retrieved 2013-01-08.

- ↑ Kreps, Daniel (18 October 2014). "Korean Safety Official Commits Suicide Following Concert Tragedy". Rolling Stone. Retrieved 19 September 2015.

- 1 2 3 4 Fu, King-Wa, C. H. Chan, and Michel Botbol. "A Study of the Impact of Thirteen Celebrity Suicides on Subsequent Suicide Rates in South Korea from 2005 to 2009." PLoS ONE, 2013, E53870.

- 1 2 Ji, Nam Ju, Weon Young Lee, Maeng Seok Noh, and Paul S.f. Yip. "The Impact of Indiscriminate Media Coverage of a Celebrity Suicide on a Society with a High Suicide Rate: Epidemiological Findings on Copycat Suicides from South Korea." Journal of Affective Disorders 156 (2014): 56-61.

- 1 2 3 Kim, K., E. Ryu, M. Chon, E. Yeun, S. Choi, J. Seo, and B. Nam. "Internet Addiction In Korean Adolescents And Its Relation To Depression And Suicidal Ideation: A Questionnaire Survey." International Journal of Nursing Studies 43, no. 2 (2006): 185-92.

- 1 2 Jeon, Hong Jin, Jin Pyo Hong, Maurizio Fava, David Mischoulon, Maren Nyer, Aya Inamori, Jee Hoon Sohn, Sujeong Seong, and Maeng Je Cho. "Childhood Parental Death and Lifetime Suicide Attempt of the Opposite-Gender Offspring in a Nationwide Community Sample of Korea." Suicide and Life-Threatening Behavior 43, no. 6 (2013): 598-610.

- 1 2 3 4 5 Chang, Shu-Sen, David Gunnell, Jonathan A.c. Sterne, Tsung-Hsueh Lu, and Andrew T.a. Cheng. "Was the Economic Crisis 1997–1998 Responsible for Rising Suicide Rates in East/Southeast Asia? A Time–trend Analysis for Japan, Hong Kong, South Korea, Taiwan, Singapore and Thailand." Social Science & Medicine 68, no. 7 (2009): 1322-331.

- 1 2 3 B. C. Ben Park; David Lester (2008). "South Korea". In Paul S. F. Yip. Suicide in Asia: Causes and Prevention. Hong Kong University Press. pp. 27–30. ISBN 978-962-209-943-2. Retrieved 14 January 2013.

- ↑ Hu, Elise (November 12 2015). "Even The Planes Stop Flying For South Korea's National Exam Day". Check date values in:

|date=(help) - ↑ Chakrabarti, Reeta (December 2 2013). "South Korea's schools: Long days, high results". Check date values in:

|date=(help) - ↑ "Lee, Gyu‐Young; Choi, Yun‐Jung; Research in Nursing & Health, Vol 38(4), Aug, 2015 pp. 301-310". 12 June 2015.

- ↑ Kang, Yewon (March 20, 2014). "Poll Shows Half of Korean Teenagers Have Suicidal Thoughts". The Wall Street Journal. Retrieved April 6, 2016.

- ↑ Koo, Se-Woong (August 1, 2014). "An Assault Upon Our Children". The New York Times. Retrieved November 25, 2015.

- ↑ Ravitch, Diane (August 3, 2014). "Why We Should Not Copy Education in South Korea". Retrieved November 25, 2015.

- ↑ Carney, Matthew (June 16, 2015). "South Korean education success has its costs in unhappiness and suicide rates". Australian Broadcasting Corporation. Retrieved April 6, 2016.

- ↑ Lee, Claire (Jan 27 2016). "Avoiding psychiatric treatment linked to Korea's high suicide rate". Check date values in:

|date=(help) - ↑ Shen, Lucinda (August 13 2015). "Here are the Vainest Countries in 2016". Check date values in:

|date=(help) - 1 2 3 4 5 6 Hendin, Herbert, Shuiyuan Xiao, Xianyun Li, Tran Thanh Huong, Hong Wang, and Ulrich Hegerl. "Suicide Prevention in Asia: Future Directions." WHO. Accessed November 4, 2014. http://www.who.int/mental_health/resources/suicide_prevention_asia_chapter10.pdf

- ↑ pbs.org South Korea announces app to combat student suicide DANIEL COSTA-ROBERTS March 15, 2015

External links

- "People & Power - South Korea: Suicide nation". Aljazeera.

- Jessica Kim, FACTBOX - Chronology of South Korean celebrity suicides