Sulmona

| Sulmona | ||

|---|---|---|

| Comune | ||

| Sulmona | ||

|

| ||

| ||

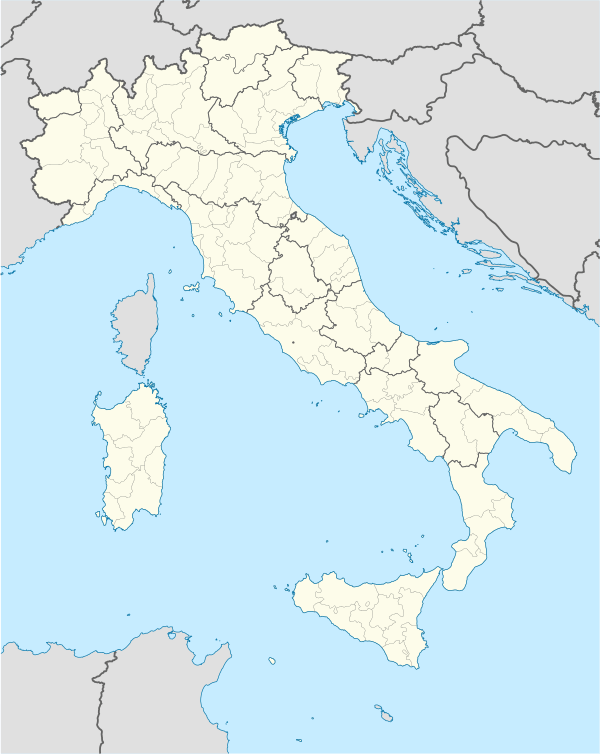

Sulmona Location of Sulmona in Italy | ||

| Coordinates: 42°02′N 13°56′E / 42.033°N 13.933°ECoordinates: 42°02′N 13°56′E / 42.033°N 13.933°E | ||

| Country | Italy | |

| Region | Abruzzo | |

| Province / Metropolitan city | L'Aquila (AQ) | |

| Frazioni | Acquasanta, Albanese, Arabona, Badia, Bagnaturo, Banchette, Case Di Censo, Case Lupi, Cavate, Colle Savente, Fonte d'Amore, Marane, Monte Morrone Scavi, Pietre Regie, Ponte Nuovo, San Rufino, Torrone | |

| Government | ||

| • Mayor | Annamaria Casini (2026) | |

| Area | ||

| • Total | 58.33 km2 (22.52 sq mi) | |

| Elevation | 405 m (1,329 ft) | |

| Population (30 June 2013) | ||

| • Total | 24,854 | |

| • Density | 430/km2 (1,100/sq mi) | |

| Demonym(s) | Sulmonesi or Sulmontini | |

| Time zone | CET (UTC+1) | |

| • Summer (DST) | CEST (UTC+2) | |

| Postal code | 67039 | |

| Dialing code | 0864 | |

| Patron saint | San Panfilo (Saint Pamphilus, Bishop of Valva-Sulmona) | |

| Saint day | April 28 | |

| Website | Official website | |

Sulmona (Latin: Sulmo; Greek: Σουλμῶν, Soulmōn) is a city and comune of the province of L'Aquila in Abruzzo, Italy. It is in Valle Peligna, a plateau once occupied by a lake that disappeared in prehistoric times. In the ancient era, it was one of the most important cities of the Paeligni and is known for being the native town of Ovid, of whom there is a bronze statue in the square known as Piazza XX Settembre located on the town's main road also under his name.

History

Ancient era

Sulmona was one of the principal cities of the Peligni, as an independent tribe, but no notice of it is found in history before the Roman conquest. A tradition alluded to by Ovid and Silius Italicus, which ascribed its foundation to Solymus, a Phrygian and one of the companions of Aeneas, is evidently a mere etymological fiction.[1] The first mention of Sulmo occurs in the Second Punic War, when its territory was ravaged by Hannibal in 211 BC, who, however, did not attack the city itself.[2] Its name is not noticed during the Social War, in which the Paeligni took so prominent a part; but according to Florus, it suffered severely in the subsequent civil war between Sulla and Gaius Marius, having been destroyed by the former as a punishment for allegiance to his rival.[3] The writings of that rhetorical writer are not, however, to be taken literally, and it is more probable that Sulmo was confiscated and its lands assigned by Sulla to a body of his soldiers.[4] In all events it is certain that Sulmo was a well-peopled and considerable town in 49 BC, when it was occupied by Domitius Calvinus with a garrison of seven cohorts; but the citizens, who were favorably inclined towards Julius Caesar, opened their gates to his lieutenant M. Antonius as soon as he presented himself.[5]

Not much more is known historically of Sulmo, which, however, appears to have continued to be a considerable provincial town. Ovid speaks of it as one of the three municipal towns whose districts composed the territory of the Paeligni:[6] and this is confirmed both by Pliny and the Liber Coloniarum; yet it does not seem to have ever been large, and Ovid himself designates it as a small provincial town.[7] From the Liber Coloniarum we learn also that it had received the status of a colony, probably in the time of Augustus;[8] though Pliny does not give it the title of a Colonia. Inscriptions, as well as the geographers and Itineraries, attest its continued existence as a municipal town throughout the Roman Empire.[9]

The chief claim to fame of Sulmona is derived from its having been the birthplace of Ovid, who repeatedly alludes to it as such, and celebrates its salubrity, and the numerous permanent streams of clear water in which its neighbourhood abounded. But, like the whole district of the Paeligni, it was extremely cold in winter, whence Ovid himself, and Silius Italicus in imitation of him, calls it "gelidus Sulmo"[10] Its territory was fertile, cultivation of both in grain and wine are common, and one district, the Pagus Fabianus, is particularly mentioned by Pliny[11] for the care bestowed on the irrigation of the vineyards.

Middle Ages and Renaissance

Traditionally, the beginning of the Christian age in Sulmona is set in the 3rd century. The city was part of the diocese of Valva, while a Sulmonese bishop is known from the 5th century. One of the earliest bishops was Saint Pamphilus (San Panfilo), an Italian pagan convert to Christianity in the 7th century from nearby Corfinium. He was elected bishop of Valva in 682 and died in 706. He is the patron saint of Sulmona and is buried in the church dedicated to him, the present Sulmona Cathedral.

Sulmona became a free commune under the Normans. Under Emperor Frederick II an aqueduct was built in the town, one of the most important construction of the era in the Abruzzo; the emperor made it the capital of a large province, as well the seat of a tribunal and of a fair, which it however lost with the arrival of the Angevins. Despite that, it continued to expand and a new line of walls was added in the 14th century.

In the 16th century a flourishing paper industry was started.

Modern age

In 1706 the city was nearly razed by an earthquake. While much of the medieval city was destroyed by the earthquake, some remarkable buildings survive such as the Church of Santa Maria della Tomba, the Palazzo Annunziata, the Aqueduct and the Gothic portal on Corso Ovidio.

Much of the city was then rebuilt in the prevailing elegant Baroque style of the 18th Century.

Sulmona experienced an economic boom in the late 19th Century due its railway hub and strategic geographic position between Rome and the Adriatic coast.

The anarchist and labor organiser Carlo Tresca was born there in 1879 and was active in the Italian Railroad Workers' Federation until emigrating to the US in 1904, to escape a prison term.

Sulmona's strategic position also made it a target for air raids during World War II. The railway station, the industrial sections and parts of the old town were damaged, but today they have been mostly restored.

Campo 78

Campo 78 at Sulmona served as a POW camp in both world wars. During World War I, it housed Austrian prisoners captured in the Isonzo and Trentino campaigns; during World War II, it was home to as many as 3,000 British and Commonwealth officers and other ranks captured in North Africa.

The camp itself was built on a hillside and consisted of a number of brick barracks surrounded by a high wall. During World War II, conditions in Sulmona, as in many Italian camps, were good, especially in the two officers’ compounds. Regular rations of macaroni soup and bread were augmented by fresh fruit and cheese in the summer, and food parcels from the International Committee of the Red Cross were distributed regularly. For recreation, the prisoners laid out a football field, and they also had equipment for cricket and basketball. There was a theater, a small lending library, at least one band, and a newspaper produced by a group of prisoners.

In September 1943, as the Italian government neared collapse, the inmates of Sulmona heard rumors that the evacuation of the camp was imminent. They awoke one morning to discover that their guards had deserted them. On 14 September, German troops arrived to escort the prisoners northwards, to captivity in Germany, but not before hundreds of them had escaped into the hills. One such escapee was the South African author, Uys Krige, who described his experience in a book titled The way out.

There were two other smaller camps nearby Fontana d'Amore which held British Officers and Villa Orsini which held very senior Allied officers captured during World War Two, including Air Marshal Owen Tudor Boyd (1889–1944), Major-General Sir Adrian Carton de Wiart (1880–1963), Brigadier James Hargest (1891–1944), Lieutenant General Sir Philip Neame (1888–1978), General Sir Richard Nugent O'Connor (1889–1981). All were subsequently transferred to Castello di Vincigliata Campo PG12 near Florence.[12]

Main sights

Sulmona has various piazzas, churches and palaces of historical and touristic interest. Some of these include:

- Sulmona Cathedral, located on the northwest side of the old city and was built on the site of a Roman temple. It contains a crypt which retains its Romanesque appearance despite the 18th-century renovation of the main church.

- Piazza XX Settembre. One of the main squares of the city, including a bronze statue of the Roman poet Ovid.

- Corso Ovidio. The city's main thoroughfare connects the cathedral and the major piazzas and is lined by elegant covered arcades, shops, cafes, palaces and churches.

- Palazzo Annunziata and Chiesa della SS. Annunziata. The Palace, one of the rare examples of late medieval/early Renaissance architecture in Sulmona that survived the earthquake of 1706. Its facade contains fine sculpture and tracery work. Inside the Palazzo is a museum showing the Roman history of the city as well as various artifacts. The church is a fine example of Baroque architecture and has a beautiful interior and bell tower.

- Piazza Garibaldi is the largest square in town with a large baroque era fountain. A Palio style medieval festival and horse race known as the Giostra Cavalleresca takes place here every year in the Summer. At Easter, crowds gather to witness the Madonna che Scappa. This ceremony involves the procession of a statue of the Madonna which is carried across the square while the bearers run to encounter a statue of the resurrected Christ on the other side of the square. On the south side of the Piazza is the 12th Century Gothic aqueduct. The square hosts a market twice a week on Wednesdays and Saturdays.

The remains of the ancient city are of little interest as ruins, but indicate the existence of a considerable town; among them are the vestiges of an amphitheatre, a theatre, and thermae, all of them located outside the gates of the modern city. About 3 km from the city, at the foot of Monte Morrone, are some ruins of reticulated masonry, traditionally believed to be Ovid's villa. Today, they are more properly identified as the sanctuary of Hercules Curinus. Nearby is the Badia Morronese, a large (c. 119 × 140 m) religious complex located near Pope Celestine V's hermitage. It was founded by Celestine as a chapel in 1241, and was enlarged and later made into a convent.

Confetti

Sulmona is the home of the Italian confectionery known as confetti. These are sugar coated almonds and are traditionally given to friends and relatives on weddings and other special occasions. Confetti can be eaten or simply used as decoration. The local artisans also color these candies and craft them into flowers and other creations. There are two main factories in town and several shops that sell these items.

Twin towns

Sports

The city has a football team, Sulmona Calcio 1921. Currently it plays in Serie D, the fifth division of Italian football.

Transports

Sulmona is served by the Sulmona railway station, an important station located at the intersection of three railway lines: the Rome–Sulmona–Pescara railway, the Terni–Sulmona railway and the Sulmona-Isernia railway.

People associated with Sulmona

- Ovidius, Roman poet

- Maurizio Bevilacqua, Canadian politician

- Virgilia D'Andrea, anarchist poet

- Cosimo de' Migliorati, Pope Innocent VII

- Carlo Tresca, anarchist labour activist, assassinated in 1943

- Nino La Civita, artist

See also

References

- ↑ Ovid, Fasti iv. 79; Silius Italicus ix. 70-76.)

- ↑ Livy xxvi. 11.

- ↑ Flor. iii. 21.

- ↑ August Wilhelm Zumpt, De Coloniis' p. 261.

- ↑ Julius Caesar Commentarii de Bello Civili i. 18; Cicero ad Att. viii. 4, 12 a.)

- ↑ "Peligni pars tertia ruris", Amor. ii. 16. 1.

- ↑ Amor. iii. 15.

- ↑ Plin. iii. 12. s. 17; Lib. Colon. pp. 229, 260.

- ↑ (Strabo v. p. 241; Ptolemy iii. 1. § 64; Tabula Peutingeriana; Orell. Inscr. 3856; Mommsen, Inscr. R. N. pp. 287–289.

- ↑ Ovid, Fasti iv. 81, Trist. iv. 10. 3, Amor. ii. 16; Sil. Ital. viii. 511.

- ↑ xvii. 26. s. 43.

- ↑ Hargest, Neame, Carton de Wiart, Leeming,

Sources

This article incorporates text from a publication now in the public domain: Smith, William, ed. (1854–1857). "article name needed". Dictionary of Greek and Roman Geography. London: John Murray.

This article incorporates text from a publication now in the public domain: Smith, William, ed. (1854–1857). "article name needed". Dictionary of Greek and Roman Geography. London: John Murray.

Relating to Sulmona POW camp, Villa Orsini and Fontana d'Amore:

- Playing with Strife, The Autobiography of a Soldier, Lt-Gen. Sir Philip Neame, V.C., K.B.E., C.B., D.S.O., George G Harrap & Co. Ltd, 1947, 353 pages,

- Farewell Campo 12, Brigadier James Hargest, C.B.E., D.S.O. M.C., Michael Joseph Ltd, 1945, 184 pages contains a sketch map of route of capture and escape 'Sidi Azir - London (inside front cover), (no index)

- Happy Odyssey, Lt-Gen. Sir Carton De Wiart, V.C., K.B.E., C.M.G., D.S.O., Jonathan Cape Ltd, 1950, in PAN paperback 1956, re-printed by Pen & Sword Books 2007, 287 pages, ISBN 1-84415-539-0 (foreword by Winston S. Churchill)

- Always To-Morrow, 1951, John F Leeming, George G Harrap & Co. Ltd, London, 188p, Illustrated with photographs and maps (Tells of the authors' experiences as a prisoner of the Italians during WW2)

- To War with Whitaker: The Wartime Diaries of the Countess of Ranfurly 1939–1945, 1994, William Heinemann Ltd, London, 375 pages, ISBN 0-434-00224-0

- The way out (Italian intermezzo), Uys Krige, (South African author), 1946, Collins, London (also Maskew Miller, Cape Town 1955 revised edition)

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Sulmona. |

| Wikivoyage has a travel guide for Sulmona. |

- Official website

- Sulmona.org, Guide to Ovidio's town

- Inside Abruzzo

- Sulmona Accommodation

- Medioeval Giostra Cavalleresca of Sulmona

- Sulmona—Pictures of Sulmona

- Rete5.tv —Sulmona online news.