Sutton Courtenay

| Sutton Courtenay | |

| All Saints' parish church |

|

Sutton Courtenay |

|

| Population | 2,421 (2011 Census) |

|---|---|

| OS grid reference | SU5094 |

| Civil parish | Sutton Courtenay |

| District | Vale of White Horse |

| Shire county | Oxfordshire |

| Region | South East |

| Country | England |

| Sovereign state | United Kingdom |

| Post town | Abingdon |

| Postcode district | OX14 |

| Dialling code | 01235 |

| Police | Thames Valley |

| Fire | Oxfordshire |

| Ambulance | South Central |

| EU Parliament | South East England |

| UK Parliament | Wantage |

| Website | Sutton Courtenay |

|

|

Coordinates: 51°38′31″N 1°16′34″W / 51.642°N 1.276°W

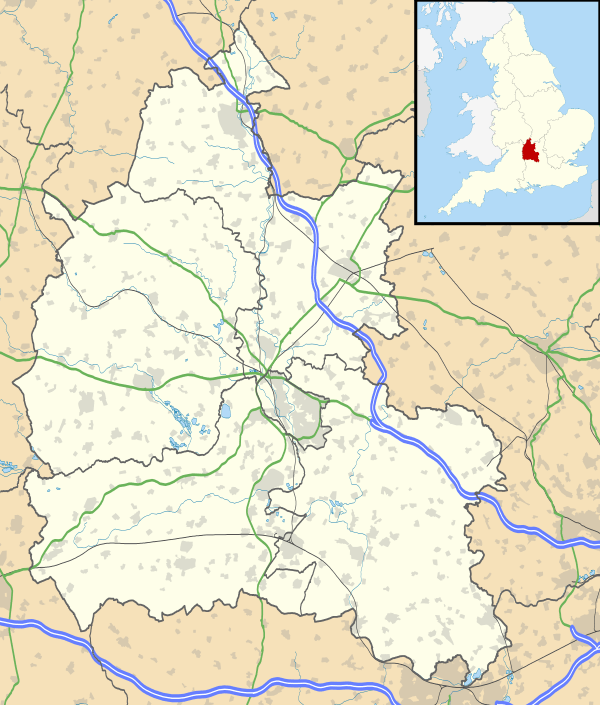

Sutton Courtenay is a village and civil parish on the River Thames 2 miles (3 km) south of Abingdon and 3 miles (5 km) northwest of Didcot. It was part of Berkshire until the 1974 boundary changes transferred it to Oxfordshire. The 2011 Census recorded the parish's population as 2,421.[1]

Archaeology and history

A Neolithic stone hand axe was found at Sutton Courtenay. Petrological analysis in 1940 identified the stone as epidotised tuff from Stake Pass in the Lake District, 250 miles (400 km) to the north. Stone axes from the same source have been found at Abingdon, Alvescot, Kencot[2] and Minster Lovell.[3]

Excavations have revealed rough Saxon huts of the early stages of Anglo-Saxon colonization,[4][5][6] but their most important enduring monument in Sutton was the massive causeway and weirs that separate the millstream from Sutton Pools. The causeway was probably built by Saxon labour. In 2010 the Channel 4 Time Team programme excavated a field in the village and discovered what they then thought was a major Anglo-Saxon royal centre with perhaps the largest great hall ever discovered in Britain.[7]

Written records of Sutton's history began in 688 when King Ine of Wessex endowed the new monastery at Abingdon with the manor of Sutton. In 801, Sutton became a royal vill,[8] with the monastery at Abingdon retaining the church and priest's house. It is believed that this was on the site of the 'Abbey' in Sutton Courtenay. The Domesday Book of 1086 shows that the manor of 'Sudtone' was owned half by the King and farmed mainly by tenants who owed him tribute. There were three mills, 300 acres (120 ha) of river meadow (probably used for dairy farming) and extensive woodlands where pigs were kept.

Sutton became known as Sutton Courtenay after the Courtenay family took residence at the Manor in the 1170s. Reginald Courtenay became the first Lord of Sutton after he had helped negotiate the path of the future king, Henry II, to the throne.[9] Most historians believe that Matilda, the elder of the two children of Henry I of England, was born in Winchester; however John M. Fletcher argues for the possibility of the royal palace at Sutton (now Sutton Courtenay) in Berkshire.

Industry and economy

In the past agriculture, a local paper mill (employing 25 people in 1840)[10] and domestic service were the main sources of employment in the village.

At one time Amey plc had its head office in Sutton Courtenay.[11] In 2003 Amey had been in financial trouble and was bought by Spain's largest construction firm, Ferrovial Servicios. At the time it employed about 400 people at Sutton Courtenay.[12]

Didcot Power Station is in Sutton Courtenay parish, as are several large quarries that have been used for gravel extraction and then used for landfill taking domestic refuse from London via a rail terminal.

Now the main employers include local scientific establishments and Didcot Power Station. There are many commuters using Didcot railway station, London being 45 minutes away.

Recent events

In August 1998 the large mock-Tudor mansion Lady Place, former home of nutritionist Hugh Macdonald Sinclair, was destroyed when fire ripped through the building.[13]

On 30 January 2008 there was an explosion and fire at Sutton Courtenay Tyres and petrol station, which led to about 100 nearby houses being evacuated for fears that acetylene cylinders might explode.[14]

Buildings

Manor houses and rectory

In the Norman era, the oldest surviving buildings of the village were built. The 'Norman Hall' is one of the oldest buildings in the village, being built in about 1192[9] in the reign of Richard I, Coeur de Lion. Across the road from the Norman Hall is The Abbey, actually the rectory house, which dates from about 1300. Its 14th-century Great Hall has an arched oak roof. The Manor House was formerly known as Brunce's Court when it was the home of the Brunce family, one of whom, Thomas Brunce, became Bishop of Norwich. It is a five-gabled, two-winged house which has had many additions over the centuries but originated as the great medieval royal hall, frequented by King Henry I and then taken over by the Courtenay family, who gave their name to the village. All Saints' Church was also built at this time (see below), and is a fine example of local Norman and Medieval architecture.

Prime Minister's home

In 1912 the Prime Minister H. H. Asquith chose The Wharf (which he built in 1913) and the adjoining Walton House for his country residence. Asquith and his large family spent weekends at The Wharf where his wife Margot held court over bridge and tennis. She converted the old barn directly on the river which served for accommodation for the overflow of her many weekend parties. A painting of the period by Sir John Lavery (now in the Hugh Lane Gallery in Dublin) shows Elizabeth Asquith and her young friends lounging in boats by the riverside. Asquith signed the declaration that took Britain into the First World War here. The house has a blue plaque in honour of Asquith.[15] He and his family remained in the village after he resigned as Prime Minister. He is buried in All Saints' churchyard (see below).

All Saints' Church

Sutton Courtenay Church, as it stands today, originated in the 12th century.[16] The interior shows Norman zig-zag work and later carved capitals. On the tower door, there are crusader crosses inscribed by soldiers either hoping for or giving thanks for a safe return from the Crusades. The main south door is surrounded by a brick-built south porch built with money left to the poor of the parish by the 15th-century Bishop Thomas Bekynton of Bath & Wells. Over the porch is a parvise reached by a narrow stairway from inside the church. Other fittings include a 17th-century wineglass pulpit (installed in 1901), a carved mid-12th century font with fleur-de-lys pattern and three late 14th-century misericords. There is a close resemblance between the misericords at Sutton Courtenay and those created shortly afterwards at Soham, Cambridgeshire and Wingfield, Suffolk. It is possible that the same itinerant carver made all three sets. The church was nearly destroyed during the Civil War when munitions stored by the Parliamentarian vicar exploded in the church.[9][16]

Churchyard

The churchyard is the burial place of Eric Arthur Blair (1903-1950), better known by his pen name, George Orwell. As a child, he fished in a local stream. He requested to be buried in an English country churchyard of the nearest church to where he died.

However, he died in London, and none of the local churches had any space in their graveyards. Thinking that he might have to be cremated against his wishes, his widow asked her friends whether they knew of a church that had space for him. David Astor, was a friend of Orwell and was able to arrange his burial in Sutton Courtenay, a 'classic English country village' as Orwell had specifically requested, as the Astor family owned the manor of Sutton Courtenay [17] With approval from the local vicar and with encouragement from Malcolm Muggeridge, arrangements were made.

The churchyard also contains the graves of David Astor and Lord H. H. Asquith, Earl of Oxford. Asquith so much loved the simplicity of the village that he chose to be buried there rather than in Westminster Abbey.

Housing Development and Major Planning Applications

In 2015, construction started on three new housing developments, Pye, Linden and Redrow, which will contribute a further 127 homes to the village. The sites for these are directly off the Milton Road. An additional housing development of 193 homes on the Amey site has also been approved. The existing infrastructure is at capacity. Grampian conditions were imposed on the new housing developments to enable upgrades to the existing sewer infrastructure. In the summer of 2015, the Redrow Asquith Park site was under investigation for breaching these conditions.[18]

Village residents are increasingly concerned about further planning applications by housing developers. The new proposals by developers are for an additional 560 residential units.

In October 2015, Redrow applied for outline planning permission for 200 homes in the field behind the Village Hall.[19] This site is known as East Sutton Courtenay. This field is adjacent to the FCC landfill and composting sites and there are recorded odour problems with this site. Residents have cited numerous reasons why the site is unsuitable including concerns about the proximity to the landfill site. Statutory consultees have also advised refusing permission for this application.

In December 2015, Savills applied for outline planning permission for 90 dwellings in the field North of Appleford Road.[20] Permission was granted for 90 dwellings at the VOWH Planning Committee in April 2016.

In March 2016, London Regeneration applied for outline planning permission for 360 residential units in the fields off Harwell Road. These fields are adjacent to the landfill and composting sites. It is also adjacent to the planned warehouse.[21]

Famous people

- H. H. Asquith, Prime Minister and Earl of Oxford, lived in The Wharf as his country home

- Margot Asquith, socialite, wife of prime minister, and countess

- David Astor, newspaper publisher, lived at the Manor House, restored The Abbey

- Thomas Bekynton, Bishop of Bath and Wells but earlier Rector of All Saints' Church

- Eric Arthur Blair (George Orwell), buried in the churchyard

- Thomas Brunce, 15th-century Bishop of Norwich, who grew up in Sutton Courtenay where his father was Lord of the Manor, then known as Brunce's Court

- Tim Burton and Helena Bonham Carter bought the Mill House in 2006, which was previously leased by her grandmother, Violet Bonham Carter, and owned by her great-grandfather H. H. Asquith[22]

- Jacques Goddet, organiser of the Tour de France, went to school here

- Empress Matilda, 12th-century "Lady of the English" and claimant of the throne of England, was probably born at the Manor House

- Hugh Macdonald Sinclair, nutritionist, lived at Lady Place in the village.

References

- ↑ "Area: Sutton Courtenay (Parish): Key Figures for 2011 Census: Key Statistics". Neighbourhood Statistics. Office for National Statistics. Retrieved 21 March 2015.

- ↑ Harden 1940, p. 165.

- ↑ Zeuner 1952, p. 240.

- ↑ Leeds, E.T. (1922–23). "A Saxon Village near Sutton Courtenay, Berkshire". Archaeologia. Society of Antiquaries of London. 73: 147–92. doi:10.1017/s0261340900010328.

- ↑ Leeds, E.T. (1926–27). "A Saxon Village near Sutton Courtenay, Berkshire (Second Report)". Archaeologia. Society of Antiquaries of London. 76: 59–80. doi:10.1017/s0261340900013229.

- ↑ Leeds, E.T. (1947). "A Saxon Village near Sutton Courtenay, Berkshire Thirdd Report". Archaeologia. Society of Antiquaries of London. 92: 79–93. doi:10.1017/s0261340900009887.

- ↑ "Sutton Courtenay Oxfordshire - Archaeological Excavation and Assessment of Results" (PDF). Time Team. Wessex Archaeology. 16 July 2014.

- ↑ Page & Ditchfield 1924, pp. 369–379

- 1 2 3 Ford, David Nash (2008). "History of Sutton Courtenay, Berkshire (Oxfordshire)". Royal Berkshire History. Nash Ford Publishing. Retrieved 22 January 2011.

- ↑ Page & Ditchfield 1924, pp. 369–379.

- ↑ "Amey bids for high-flying firm". Oxford Mail. Newsquest. 27 January 1999. Retrieved 13 August 2011.

- ↑ "Amey takeover wins approval". Oxford Mail. Newsquest. 2 June 2003. Retrieved 14 September 2011.

- ↑ "Blaze rips through mansion". Oxford Mail. Newsquest Oxfordshire. 29 August 1998.

- ↑ "Investigation into garage blaze". BBC.

- ↑ "H. H. Asquith (1852–1928)". Oxfordshire Blue Plaques Scheme. Oxfordshire Blue Plaques Board.

- 1 2 Ford, David Nash (2001). "Sutton Courtenay Parish Church". Royal Berkshire History. Nash Ford Publishing. Retrieved 22 January 2011.

- ↑ Marilyn Yurdan Oxfordshire Graves & Gravestones - the History Press 2010

- ↑ "Residents claim housebuilder has breached planning rules". Herald Series. Retrieved 2015-11-21.

- ↑ "Planning Application P15/V2353/O". www.whitehorsedc.gov.uk. Retrieved 2015-11-21.

- ↑ Planning Application P15/V2933/O

- ↑ Planning Application P16/V0646/O

- ↑ "Bonham Carter buys back family heritage for £2.9m". The Daily Telegraph. Retrieved 11 January 2013.

Sources and further reading

- Harden, D.B. (1940). "The Geological Origin of Four Stone Axes Found in the Oxford District" (PDF). Oxoniensia. Oxford Architectural and Historical Society. V: 165.

- Page, W.H.; Ditchfield, P.H., eds. (1924). A History of the County of Berkshire. Victoria County History. 4. assisted by John Hautenville Cope. London: The St Katherine Press. pp. 369–379.

- Pevsner, Nikolaus (1966). Berkshire. The Buildings of England. Harmondsworth: Penguin Books. pp. 235–237.

- Zeuner, F.E. (1952). "A group VI neolithic axe from Minster Lovell, Oxfordshire". Proceedings of the Prehistoric Society. Cambridge University Press for The Prehistoric Society. XVIII (2): 240–241. doi:10.1017/s0079497x00018387. ISSN 0958-8418.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Sutton Courtenay. |

- Map sources for Sutton Courtenay

- Sutton Courtenay Village Website

- The Abbey at Sutton Courtenay