Tetzaveh

.jpg)

Tetzaveh, Tetsaveh, T'tzaveh, or T'tzavveh (תְּצַוֶּה — Hebrew for "you command," the second word and first distinctive word in the parashah) is the 20th weekly Torah portion (פָּרָשָׁה, parashah) in the annual Jewish cycle of Torah reading and the eighth in the Book of Exodus. It constitutes Exodus 27:20–30:10. The parashah is made up of 5,430 Hebrew letters, 1,412 Hebrew words, and 101 verses, and can occupy about 179 lines in a Torah Scroll (סֵפֶר תּוֹרָה, Sefer Torah).[1] Jews read it the 20th Sabbath after Simchat Torah, in February or March.[2]

The parashah reports God's commands to bring olive oil for the lamp, to make sacred garments for the priests, to conduct an ordination ceremony, and to make an incense altar.

Readings

In traditional Sabbath Torah reading, the parashah is divided into seven readings, or עליות, aliyot.[3]

First reading — Exodus 27:20–28:12

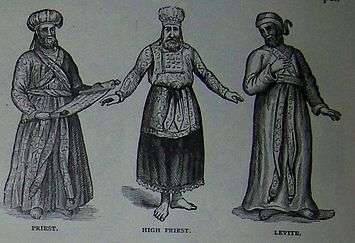

In the first reading (עליה, aliyah), God instructed the Israelites to bring Moses clear olive oil, so that Aaron and his descendants as High Priest could kindle lamps regularly in the Tabernacle.[4] God instructed Moses to make sacral vestments for Aaron: a breastpiece (the Hoshen), the Ephod, a robe, a gold frontlet inscribed "holy to the Lord," a fringed tunic, a headdress, a sash, and linen breeches.[5]

Second reading — Exodus 28:13–30

In the second reading (עליה, aliyah), God detailed the instructions for the breastpiece.[6] God instructed Moses to place Urim and Thummim inside the breastpiece of decision.[7]

Third reading — Exodus 28:31–43

In the third reading (עליה, aliyah), God detailed the instructions for the robe, frontlet, fringed tunic, headdress, sash, and breeches.[8] God instructed Moses to place pomegranates and gold bells around the robe's hem, to make a sound when the High Priest entered and exited the sanctuary, so that he not die.[9]

Fourth reading — Exodus 29:1–18

In the fourth reading (עליה, aliyah), God laid out an ordination ceremony for priests involving the sacrifice of a young bull, two rams, unleavened bread, unleavened cakes with oil mixed in, and unleavened wafers spread with oil.[10] God instructed Moses to lead the bull to the front of the Tabernacle, let Aaron and his sons lay their hands upon the bull's head, slaughter the bull at the entrance of the Tent, and put some of the bull's blood on the horns of the altar.[11]

Fifth reading — Exodus 29:19–37

In the fifth reading (עליה, aliyah), God instructed Moses to take one of the rams, let Aaron and his sons lay their hands upon the ram's head, slaughter the ram, and put some of its blood and on the ridge of Aaron's right ear and on the ridges of his sons' right ears, and on the thumbs of their right hands, and on the big toes of their right feet.[12]

Sixth reading — Exodus 29:38–46

In the sixth reading (עליה, aliyah), God promised to meet and speak with Moses and the Israelites there, to abide among the Israelites, and be their God.[13]

Seventh reading — Exodus 30:1–10

In the seventh reading (עליה, aliyah), God instructed Moses to make an incense altar of acacia wood overlaid with gold—sometimes called the Golden Altar.[14]

Readings according to the triennial cycle

Jews who read the Torah according to the triennial cycle of Torah reading read the parashah according to the following schedule:[15]

| Year 1 | Year 2 | Year 3 | |

|---|---|---|---|

| 2013–2014, 2016–2017, 2019–2020 ... | 2014–2015, 2017–2018, 2020–2021 ... | 2015–2016, 2018–2019, 2021–2022 ... | |

| Reading | 27:20–28:30 | 28:31–29:18 | 29:19–30:10 |

| 1 | 27:20–28:5 | 28:31–35 | 29:19–21 |

| 2 | 28:6–9 | 28:36–38 | 29:22–25 |

| 3 | 28:10–12 | 28:39–43 | 29:26–30 |

| 4 | 28:13–17 | 29:1–4 | 29:31–34 |

| 5 | 28:18–21 | 29:5–9 | 29:35–37 |

| 6 | 28:22–25 | 29:10–14 | 29:38–46 |

| 7 | 28:26–30 | 29:15–18 | 30:1–10 |

| Maftir | 28:28–30 | 29:15–18 | 30:8–10 |

In inner-Biblical interpretation

The parashah has parallels or is discussed in these Biblical sources:[16]

Exodus chapters 25–39

This is the pattern of instruction and construction of the Tabernacle and its furnishings:

| Item | Instruction | Construction | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Order | Verses | Order | Verses | |

| Contributions | 1 | Exodus 25:1–9 | 2 | Exodus 35:4–29 |

| Ark | 2 | Exodus 25:10–22 | 5 | Exodus 37:1–9 |

| Table | 3 | Exodus 25:23–30 | 6 | Exodus 37:10–16 |

| Menorah | 4 | Exodus 25:31–40 | 7 | Exodus 37:17–24 |

| Tabernacle | 5 | Exodus 26:1–37 | 4 | Exodus 36:8–38 |

| Altar of Sacrifice | 6 | Exodus 27:1–8 | 11 | Exodus 38:1–7 |

| Tabernacle Court | 7 | Exodus 27:9–19 | 13 | Exodus 38:9–20 |

| Lamp | 8 | Exodus 27:20–21 | 16 | Numbers 8:1–4 |

| Priestly Garments | 9 | Exodus 28:1–43 | 14 | Exodus 39:1–31 |

| Ordination Ritual | 10 | Exodus 29:1–46 | 15 | Leviticus 8:1–9:24 |

| Altar of Incense | 11 | Exodus 30:1–10 | 8 | Exodus 37:25–28 |

| Laver | 12 | Exodus 30:17–21 | 12 | Exodus 38:8 |

| Anointing Oil | 13 | Exodus 30:22–33 | 9 | Exodus 37:29 |

| Incense | 14 | Exodus 30:34–38 | 10 | Exodus 37:29 |

| Craftspeople | 15 | Exodus 31:1–11 | 3 | Exodus 35:30–36:7 |

| The Sabbath | 16 | Exodus 31:12–17 | 1 | Exodus 35:1–3 |

The Priestly story of the Tabernacle in Exodus 25–27 echoes the Priestly story of creation in Genesis 1:1–2:3.[17] As the creation story unfolds in seven days,[18] the instructions about the Tabernacle unfold in seven speeches.[19] In both creation and Tabernacle accounts, the text notes the completion of the task.[20] In both creation and Tabernacle, the work done is seen to be good.[21] In both creation and Tabernacle, when the work is finished, God takes an action in acknowledgement.[22] In both creation and Tabernacle, when the work is finished, a blessing is invoked.[23] And in both creation and Tabernacle, God declares something "holy."[24]

Martin Buber and others noted that the language used to describe the building of the Tabernacle parallels that used in the story of creation.[25] Jeffrey Tigay noted[26] that the lampstand held seven candles,[27] Aaron wore seven sacral vestments,[28] the account of the building of the Tabernacle alludes to the creation account,[29] and the Tabernacle was completed on New Year’s day.[30] And Carol Meyers noted that Exodus 25:1–9 and 35:4–29 list seven kinds of substances — metals, yarn, skins, wood, oil, spices, and gemstones — signifying the totality of supplies.[31]

Exodus chapter 28

The priestly garments of Exodus 28:2–43 are echoed in Psalm 132:9, where the Psalmist exhorts, “Let Your priests be clothed with righteousness,” and in Psalm 132:16, where God promises, “Her priests also will I clothe with salvation.”[32]

The Hebrew Bible refers to the Urim and Thummim in Exodus 28:30; Leviticus 8:8; Numbers 27:21; Deuteronomy 33:8; 1 Samuel 14:41 ("Thammim") and 28:6; Ezra 2:63; and Nehemiah 7:65; and may refer to them in references to "sacred utensils" in Numbers 31:6 and the Ephod in 1 Samuel 14:3 and 19; 23:6 and 9; and 30:7–8; and Hosea 3:4.

Exodus chapter 29

The Torah mentions the combination of ear, thumb, and toe in three places. In Exodus 29:20, God instructed Moses how to initiate the priests, telling him to kill a ram, take some of its blood, and put it on the tip of the right ear of Aaron and his sons, on the thumb of their right hand, and on the great toe of their right foot, and dash the remaining blood against the altar round about. And then Leviticus 8:23–24 reports that Moses followed God's instructions to initiate Aaron and his sons. Then, Leviticus 14:14, 17, 25, and 28 set forth a similar procedure for the cleansing of a person with skin disease (צָּרַעַת, tzara'at). In Leviticus 14:14, God instructed the priest on the day of the person's cleansing to take some of the blood of a guilt-offering and put it upon the tip of the right ear, the thumb of the right hand, and the great toe of the right foot of the one to be cleansed. And then in Leviticus 14:17, God instructed the priest to put oil on the tip of the right ear, the thumb of the right hand, and the great toe of the right foot of the one to be cleansed, on top of the blood of the guilt-offering. And finally, in Leviticus 14:25 and 28, God instructed the priest to repeat the procedure on the eighth day to complete the person's cleansing.

In early nonrabbinic interpretation

The parashah is discussed in these early nonrabbinic sources:[33]

Exodus chapter 28

Ben Sira wrote of the splendor of the High Priest’s garments in Exodus 28, saying “How glorious he was . . . as he came out of the House of the curtain. Like the morning star among the clouds, like the full moon at the festal season; like the sun shining on the Temple of the Most High, like the rainbow gleaming in splendid clouds.”[34]

Josephus interpreted the linen vestment of Exodus 28:5 to signify the earth, as flax grows out of the earth. Josephus interpreted the Ephod of the four colors gold, blue, purple, and scarlet[35] to signify that God made the universe of four elements, with the gold interwoven to show the splendor by which all things are enlightened. Josephus saw the stones on the High Priest's shoulders in Exodus 28:9–12 to represent the sun and the moon. He interpreted the breastplate of Exodus 28:15–22 to resemble the earth, having the middle place of the world, and the girdle that encompassed the High Priest to signify the ocean, which encircled the world. He interpreted the 12 stones of the Ephod in Exodus 28:17–21 to represent the months or the signs of the Zodiac. He interpreted the golden bells and pomegranates that Exodus 28:33–35 says hung on the fringes of the High Priest's garments to signify thunder and lightning, respectively. And Josephus saw the blue on the headdress of Exodus 28:37 to represent heaven, "for how otherwise could the name of God be inscribed upon it?"[36]

Exodus chapter 29

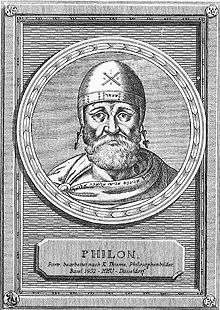

Philo taught that the command of Exodus 29:20 to apply ram's blood to the priests' right ear, right thumb, and right great toe signified that the perfect person must be pure in every word, every action, and the entirety of life. For the ear symbolized the hearing with which people judge one's words, the hand symbolized action, and the foot symbolized the way in which a person walks in life. And since each of these is an extremity of the right side of the body, Philo imagined that Exodus 29:20 teaches that one should labor to attain improvement in everything with dexterity and felicity, as an archer aims at a target.[37]

In classical rabbinic interpretation

The parashah is discussed in these rabbinic sources from the era of the Mishnah and the Talmud:[38]

Exodus chapter 27

It was taught in a Baraita that Rabbi Josiah taught that the expression "they shall take for you" (וְיִקְחוּ אֵלֶיךָ, v'yikhu eileicha) in Exodus 27:20 was a command for Moses to take from communal funds, in contrast to the expression "make for yourself" (עֲשֵׂה לְךָ, aseih lecha) in Numbers 10:2, which was a command for Moses to take from his own funds.[39]

The Mishnah posited that one could have inferred that meal-offerings would require the purest olive oil, for if the menorah, whose oil was not eaten, required pure olive oil, how much more so should meal-offerings, whose oil was eaten. But Exodus 27:20 states, "pure olive oil beaten for the light," but not "pure olive oil beaten for meal-offerings," to make clear that such purity was required only for the menorah and not for meal-offerings.[40] The Mishnah taught that there were three harvests of olives, and each crop gave three kinds of oil (for a total of nine types of oil). The first crop of olives were picked from the top of the tree; they were pounded and put into a basket (Rabbi Judah said around the inside of the basket) to yield the first oil. The olives were then pressed beneath a beam (Rabbi Judah said with stones) to yield the second oil. The olives were then ground and pressed again to yield the third oil. Only the first oil was fit for the menorah, while the second and third were for meal-offerings. The second crop is when the olives at roof-level were picked from the tree; they were pounded and put into the basket (Rabbi Judah said around the inside of the basket) to yield the first oil (of the second crop). The olives were then pressed with the beam (Rabbi Judah said with stones) to yield the second oil (of the second crop). The olives were then ground and pressed again to yield the third oil. Once again, with the second crop, only the first oil was fit for the menorah, while the second and third were for meal-offerings. The third crop was when the last olives of the tree were packed in a vat until they became overripe. These olives were then taken up and dried on the roof and then pounded and put into the basket (Rabbi Judah said around the inside of the basket) to yield the first oil. The olives were next pressed with the beam (Rabbi Judah said with stones) to yield the second oil. And then they were ground and pressed again to yield the third oil. Once again, with the third crop, only the first oil was fit for the menorah, while the second and third were for meal-offerings.[41]

The Mishnah taught that there was a stone in front of the menorah with three steps on which the priest stood to trim the lights. The priest left the oil jar on the second step.[42]

A Midrash taught that the lights of the Tabernacle menorah were replicas of the heavenly lights. The Midrash taught that everything God created in heaven has a replica on earth. Thus Daniel 2:22 reports, "And the light dwells with [God]" in heaven. While below on earth, Exodus 27:20 directs, "That they bring to you pure olive-oil beaten for the light." (Thus, since all that is above is also below, God dwells on earth just as God dwells in heaven.) What is more, the Midrash taught that God holds the things below dearer than those above, for God left the things in heaven to descend to dwell among those below, as Exodus 25:8 reports, "And let them make Me a sanctuary, that I may dwell among them."[43]

A Midrash expounded on Exodus 27:20 to explain why Israel was, in the words of Jeremiah 11:16, like "a leafy olive tree." The Midrash taught that just as the olive is beaten, ground, tied up with ropes, and then at last it yields its oil, so the nations beat, imprisoned, bound, and surrounded Israel, and when at last Israel repents of its sins, God answers it. The Midrash offered a second explanation: Just as all liquids commingle one with the other, but oil refuses to do so, so Israel keeps itself distinct, as it is commanded in Deuteronomy 7:3. The Midrash offered a third explanation: Just as oil floats to the top even after it has been mixed with every kind of liquid, so Israel, as long as it performs the will of God, will be set on high by God, as it says in Deuteronomy 28:1. The Midrash offered a fourth explanation: Just as oil gives forth light, so did the Temple in Jerusalem give light to the whole world, as it says in Isaiah 60:3.[44]

.jpg)

A Midrash taught that God instructed Moses to cause a lamp to burn in the Tabernacle not because God needed the light, but so that the Israelites might be able to give light to God as God gave light to the Israelites. The Midrash likened this to the case of a man who could see, walking along with a blind man. The seeing man offered to guide the blind man. When they came home, the seeing man asked the blind man to kindle a lamp for him and illumine his path, so that the blind man would no longer be obliged to the seeing man for having accompanied the blind man on the way. The seeing man of the story is God, for 2 Chronicles 16:9 and Zechariah 4:10 say, "For the eyes of the Lord run to and fro throughout the whole earth." And the blind man is Israel, as Isaiah 59:10 says, "We grope for the wall like the blind, yea, as they that have no eyes do we grope; we stumble at noon-day as in the twilight" (and the Israelites stumbled in the matter of the Golden Calf at midday). God illumined the way for the Israelites (after they stumbled with the Calf) and led them, as Exodus 13:21 says, "And the Lord went before them by day." And then when the Israelites were about to construct the Tabernacle, God called to Moses and asked him in Exodus 27:20, "that they bring to you pure olive oil."[45]

Another Midrash taught that the words of the Torah give light to those who study them, but those who do not occupy themselves with the Torah stumble. The Midrash compared this to those who stand in the dark; as soon as they start walking, they stumble, fall, and knock their face on the ground — all because they have no lamp in their hand. It is the same with those who have no Torah; they strike against sin, stumble, and die. The Midrash further taught that those who study the Torah give forth light wherever they may be. Quoting Psalm 119:105, "Your word is a lamp to my feet, and a light to my path," and Proverbs 20:27, "The spirit of man is the lamp of the Lord," the Midrash taught that God offers people to let God's lamp (the Torah) be in their hand and their lamp (their souls) be in God's hand. The lamp of God is the Torah, as Proverbs 6:23 says, "For the commandment is a lamp, and the teaching is light." The commandment is "a lamp" because those who perform a commandment kindle a light before God and revive their souls, as Proverbs 20:27 says, "The spirit of man is the lamp of the Lord."[46]

A Baraita taught that they used the High Priest's worn-out trousers to make the wicks of the Temple menorah and the worn-out trousers of ordinary priests for candelabra outside the Temple. Reading the words "to cause a lamp to burn continually" in Exodus 27:20, Rabbi Samuel bar Isaac deduced that the unusual word לְהַעֲלֹת, lehaalot, literally "to cause to ascend," meant that the wick had to allow the flame to ascend by itself. And thus the Rabbis concluded that no material other than flax—as in the fine linen of the High Priest's clothing—would allow the flame to ascend by itself.[47] Similarly, Rami bar Hama deduced from the use of word לְהַעֲלֹת, lehaalot, in Exodus 27:20 that the menorah flame had to ascend by itself, and not through other means (such as adjustment by the priests). Thus Rami bar Hama taught that the wicks and oil that the Sages taught one could not light on the Sabbath, one could also not light in the Temple.[48] The Gemara challenged Rami bar Hama, however, citing a Mishnah[49] that taught that the worn-out breeches and girdles of priests were torn and used to kindle the lights for the celebration of the Water-Drawing. The Gemara posited that perhaps that celebration was different. The Gemara countered with the teaching of Rabbah bar Masnah, who taught that worn-out priestly garments were torn and made into wicks for the Temple. And the Gemara clarified that the linen garments were meant.[48]

Exodus chapter 28

In Exodus 28:1, God chose Aaron and his sons to minister to God in the priest's office. Hillel taught that Aaron loved peace and pursued peace, and loved his fellow creatures and brought them closer to the Torah.[50] Rabbi Simeon bar Yochai taught that because Aaron was, in the words of Exodus 4:14, “glad in his heart” over the success of Moses, in the words of Exodus 28:30, “the breastplate of judgment the Urim and the Thummim . . . shall be upon Aaron's heart.”[51]

.jpg)

Interpreting God’s command in Exodus 28:1, the Sages told that when Moses came down from Mount Sinai, he saw Aaron beating the Golden Calf into shape with a hammer. Aaron really intended to delay the people until Moses came down, but Moses thought that Aaron was participating in the sin and was incensed with him. So God told Moses that God knew that Aaron's intentions were good. The Midrash compared it to a prince who became mentally unstable and started digging to undermine his father's house. His tutor told him not to weary himself but to let him dig. When the king saw it, he said that he knew the tutor’s intentions were good, and declared that the tutor would rule over the palace. Similarly, when the Israelites told Aaron in Exodus 32:1, “Make us a god,” Aaron replied in Exodus 32:1, “Break off the golden rings that are in the ears of your wives, of your sons, and of your daughters, and bring them to me.” And Aaron told them that since he was a priest, they should let him make it and sacrifice to it, all with the intention of delaying them until Moses could come down. So God told Aaron that God knew Aaron’s intention, and that only Aaron would have sovereignty over the sacrifices that the Israelites would bring. Hence in Exodus 28:1, God told Moses, “And bring near Aaron your brother, and his sons with him, from among the children of Israel, that they may minister to Me in the priest's office.” The Midrash told that God told this to Moses several months later in the Tabernacle itself when Moses was about to consecrate Aaron to his office. Rabbi Levi compared it to the friend of a king who was a member of the imperial cabinet and a judge. When the king was about to appoint a palace governor, he told his friend that he intended to appoint the friend’s brother. So God made Moses superintendent of the palace, as Numbers 7:7 reports, “My servant Moses is . . . is trusted in all My house,” and God made Moses a judge, as Exodus 18:13 reports, “Moses sat to judge the people.” And when God was about to appoint a High Priest, God notified Moses that it would be his brother Aaron.[52]

The Mishnah summarized the priestly garments described in Exodus 28, saying that "the High Priest performs the service in eight garments, and the common priest in four: in tunic, drawers, miter, and girdle. The High Priest adds to those the breastplate, the apron, the robe, and the frontlet. And the High Priest wore these eight garments when he inquired of the Urim and Thummim.[53]

Rabbi Johanan called his garments "my honor." Rabbi Aha bar Abba said in Rabbi Johanan's name that Leviticus 6:4, "And he shall put off his garments, and put on other garments," teaches that a change of garments is an act of honor in the Torah. And the School of Rabbi Ishmael taught that the Torah teaches us manners: In the garments in which one cooked a dish for one's master, one should not pour a cup of wine for one's master. Rabbi Hiyya bar Abba said in Rabbi Johanan's name that it is a disgrace for a scholar to go out into the marketplace with patched shoes. The Gemara objected that Rabbi Aha bar Hanina went out that way; Rabbi Aha son of Rav Nachman clarified that the prohibition is of patches upon patches. Rabbi Hiyya bar Abba also said in Rabbi Johanan's name that any scholar who has a grease stain on a garment is worthy of death, for Wisdom says in Proverbs 8:36, "All they that hate me (מְשַׂנְאַי, mesanne'ai) love (merit) death," and we should read not מְשַׂנְאַי, mesanne'ai, but משׂניאי, masni'ai (that make me hated, that is, despised). Thus a scholar who has no pride in personal appearance brings contempt upon learning. Ravina taught that this was stated about a thick patch (or others say, a bloodstain). The Gemara harmonized the two opinions by teaching that one referred to an outer garment, the other to an undergarment. Rabbi Hiyya bar Abba also said in Rabbi Johanan's name that in Isaiah 20:3, "As my servant Isaiah walked naked and barefoot," "naked" means in worn-out garments, and "barefoot" means in patched shoes.[54]

Rabbi Hama bar Hanina interpreted the words "the plaited (שְּׂרָד, serad) garments for ministering in the holy place" in Exodus 35:19 to teach that but for the priestly garments described in Exodus 28 (and the atonement achieved by the garments or the priests who wore them), no remnant (שָׂרִיד, sarid) of the Jews would have survived.[55] Similarly, citing Mishnah Yoma 7:5,[53] Rabbi Simon taught that even as the sacrifices had an atoning power, so too did the priestly garments. Rabbi Simon explained that the priests' tunic atoned for those who wore a mixture of wool and linen (שַׁעַטְנֵז, shaatnez, prohibited by Deuteronomy 22:11), as Genesis 37:3 says, "And he made him a coat (tunic) of many colors" (and the Jerusalem Talmud explained that Joseph's coat was similar to one made of the forbidden mixture). The breeches atoned for unchastity, as Exodus 28:42 says, "And you shall make them linen breeches to cover the flesh of their nakedness." The miter atoned for arrogance, as Exodus 29:6 says, "And you shall set the miter on his head." Some said that the girdle atoned for the crooked in heart, and others said for thieves. Rabbi Levi said that the girdle was 32 cubits long (about 48 feet), and that the priest wound it towards the front and towards the back, and this was the ground for saying that it was to atone for the crooked in heart (as the numerical value of the Hebrew word for heart is 32). The one who said that the girdle atoned for thieves argued that since the girdle was hollow, it resembled thieves, who do their work in secret, hiding their stolen goods in hollows and caves. The breastplate atoned for those who pervert justice, as Exodus 28:30 says, "And you shall put in the breastplate of judgment." The Ephod atoned for idol-worshippers, as Hosea 3:4 says, "and without Ephod or teraphim." Rabbi Simon taught in the name of Rabbi Nathan that the robe atoned for two sins, unintentional manslaughter (for which the Torah provided cities of refuge) and evil speech.[56]

The robe atoned for evil speech by the bells on its fringe, as Exodus 28:34–35 says, "A golden bell and a pomegranate, a golden bell and a pomegranate, upon the skirts of the robe round about. And it shall be upon Aaron to minister, and the sound thereof shall be heard." Exodus 28:34–35 thus implies that this sound made atonement for the sound of evil speech. There is not strictly atonement for one who unintentionally slays a human being, but the Torah provides a means of atonement by the death of the High Priest, as Numbers 35:28 says, "after the death of the High Priest the manslayer may return to the land of his possession." Some said that the forehead-plate atoned for the shameless, while others said for blasphemers. Those who said that it atoned for the shameless deduced it from the similar use of the word "forehead" in Exodus 28:38, which says of the forehead-plate, "And it shall be upon Aaron's forehead," and Jeremiah 3:3, which says, "You had a harlot's forehead, you refused to be ashamed." Those who said that the forehead-plate atoned for blasphemers deduced it from the similar use of the word "forehead" in Exodus 28:38 and 1 Samuel 17:48, which says of Goliath, "And the stone sank into his forehead."[57]

A Baraita interpreted the term "his fitted linen garment" (מִדּוֹ, mido) in Leviticus 6:3 to teach that the each priestly garment in Exodus 28 had to be fitted to the particular priest, and had to be neither too short nor too long.[58]

The Rabbis taught in a Baraita that the robe (מְעִיל, me'il) mentioned in Exodus 28:4 was entirely of turquoise (תְּכֵלֶת, techelet), as Exodus 39:22 says, "And he made the robe of the ephod of woven work, all of turquoise." They made its hems of turquoise, purple, and crimson wool, twisted together and formed into the shape of pomegranates whose mouths were not yet opened (as overripe pomegranates open slightly) and in the shape of the cones of the helmets on children's heads. Seventy two bells containing 72 clappers were hung on the robe, 36 on each side (front and behind). Rabbi Dosa (or others say, Judah the Prince) said in the name of Rabbi Judah that there were 36 bells in all, 18 on each side.[59]

Rabbi Eleazar deduced from the words "that the breastplate not be loosed from the Ephod" in Exodus 28:28 that one who removed the breastplate from the apron received the punishment of lashes. Rav Aha bar Jacob objected that perhaps Exodus 28:28 meant merely to instruct the Israelites to fasten the breast-plate securely so that it would "not be loosed." But the Gemara noted that Exodus 28:28 does not say merely, "so that it not be loosed."[60]

The Mishnah taught that the High Priest inquired of the Urim and Thummim noted in Exodus 28:30 only for the king, for the court, or for one whom the community needed.[53]

A Baraita explained why the Urim and Thummim noted in Exodus 28:30 were called by those names: The term "Urim" is like the Hebrew word for "lights," and thus it was called "Urim" because it enlightened. The term "Thummim" is like the Hebrew word tam meaning "to be complete," and thus it was called "Thummim" because its predictions were fulfilled. The Gemara discussed how they used the Urim and Thummim: Rabbi Johanan said that the letters of the stones in the breastplate stood out to spell out the answer. Resh Lakish said that the letters joined each other to spell words. But the Gemara noted that the Hebrew letter צ, tsade, was missing from the list of the 12 tribes of Israel. Rabbi Samuel bar Isaac said that the stones of the breastplate also contained the names of Abraham, Isaac and Jacob. But the Gemara noted that the Hebrew letter ט, teth, was also missing. Rav Aha bar Jacob said that they also contained the words: "The tribes of Jeshurun." The Gemara taught that although the decree of a prophet could be revoked, the decree of the Urim and Thummim could not be revoked, as Numbers 27:21 says, "By the judgment of the Urim."[61]

.jpg)

The Pirke De-Rabbi Eliezer taught that when Israel sinned in the matter of the devoted things, as reported in Joshua 7:11, Joshua looked at the 12 stones corresponding to the 12 tribes that were upon the High Priest's breastplate. For every tribe that had sinned, the light of its stone became dim, and Joshua saw that the light of the stone for the tribe of Judah had become dim. So Joshua knew that the tribe of Judah had transgressed in the matter of the devoted things. Similarly, the Pirke De-Rabbi Eliezer taught that Saul saw the Philistines turning against Israel, and he knew that Israel had sinned in the matter of the ban. Saul looked at the 12 stones, and for each tribe that had followed the law, its stone (on the High Priest's breastplate) shined with its light, and for each tribe that had transgressed, the light of its stone was dim. So Saul knew that the tribe of Benjamin had trespassed in the matter of the ban.[62]

The Mishnah reported that with the death of the former prophets, the Urim and Thummim ceased.[63] In this connection, the Gemara reported differing views of who the former prophets were. Rav Huna said they were David, Samuel, and Solomon. Rav Nachman said that during the days of David, they were sometimes successful and sometimes not (getting an answer from the Urim and Thummim), for Zadok consulted it and succeeded, while Abiathar consulted it and was not successful, as 2 Samuel 15:24 reports, "And Abiathar went up." (He retired from the priesthood because the Urim and Thummim gave him no reply.) Rabbah bar Samuel asked whether the report of 2 Chronicles 26:5, "And he (King Uzziah of Judah) set himself to seek God all the days of Zechariah, who had understanding in the vision of God," did not refer to the Urim and Thummim. But the Gemara answered that Uzziah did so through Zechariah's prophecy. A Baraita told that when the first Temple was destroyed, the Urim and Thummim ceased, and explained Ezra 2:63 (reporting events after the Jews returned from the Babylonian Captivity), "And the governor said to them that they should not eat of the most holy things till there stood up a priest with Urim and Thummim," as a reference to the remote future, as when one speaks of the time of the Messiah. Rav Nachman concluded that the term "former prophets" referred to a period before Haggai, Zechariah, and Malachi, who were latter prophets.[64] And the Jerusalem Talmud taught that the "former prophets" referred to Samuel and David, and thus the Urim and Thummim did not function in the period of the First Temple, either.[65]

Rabbi Hanina ben Gamaliel interpreted the words "completely blue (תְּכֵלֶת, tekhelet)" in Exodus 28:31 to teach that blue dye used to test the dye is unfit for further use to dye the blue, tekhelet strand of a tzitzit, interpreting the word "completely" to mean "full strength." But Rabbi Johanan ben Dahabai taught that even the second dyeing using the same dye is valid, reading the words "and scarlet" (וּשְׁנִי תוֹלַעַת, ushni tolalat) in Leviticus 14:4 to mean "a second [dying] of red wool."[66]

The Gemara reported that some interpreted the words "woven work" in Exodus 28:32 to teach that all priestly garments were made entirely by weaving, without needlework. But Abaye interpreted a saying of Resh Lakish and a Baraita to teach that the sleeves of the priestly garments were woven separately and then attached to the garment using needlework, and the sleeves reached down to the priest's wrist.[67]

Rehava said in the name of Rav Judah that one who tore a priestly garment was liable to punishment with lashes, for Exodus 28:32 says "that it be not rent." Rav Aha bar Jacob objected that perhaps Exodus 28:32 meant to instruct that the Israelites make a hem so that the garment would not tear. But the Gemara noted that Exodus 28:32 does not say merely, "lest it be torn."[60]

A Baraita taught that the golden head-plate of Exodus 28:36–38 was two fingerbreadths wide and stretched around the High Priest's forehead from ear to ear. The Baraita taught that two lines were written on it, with the four-letter name of God יהוה on the top line and "holy to" (קֹדֶשׁ לַ, kodesh la) on the bottom line. But Rabbi Eliezer son of Rabbi Jose said that he saw it in Rome (where it was taken after the destruction of the Temple) and "holy to the Lord" (קֹדֶשׁ לַיהוה) was written in one line.[68]

Rabbi (Judah the Prince) taught that there was no difference between the tunic, belt, turban, and breeches of the High Priest and those of the common priest in Exodus 28:40–43, except in the belt. Rabbi Eleazar the son of Rabbi Simeon taught that there was not even any distinction in the belt. Ravin reported that all agree that on Yom Kippur, the High Priest's belt was made of fine linen (as stated in Leviticus 16:4), and during the rest of the year a belt made of both wool and linen (shatnez) (as stated in Exodus 39:29). The difference concerned only the common priest's belt, both on the Day of Atonement and during the rest of the year. Concerning that, Rabbi said it was made of both wool and linen, and Rabbi Eleazar the son of Rabbi Simeon said it was made of fine linen.[69]

A Baraita taught that the priests' breeches of Exodus 28:42 were like the knee breeches of horsemen, reaching upwards to the hips and downwards to the thighs. They had laces but had no padding in either back or front (and thus fit loosely).[70]

.jpg)

Exodus chapter 29

A Baraita taught that a priest who performed sacrifices without the proper priestly garments was liable to death at the hands of Heaven.[71] Rabbi Abbahu said in the name of Rabbi Johanan's (or some say Rabbi Eleazar son of Rabbi Simeon) that the Baraita's teaching was derived from Exodus 29:9, which says: "And you shall gird them with girdles, Aaron and his sons, and bind turbans on them; and they shall have the priesthood by a perpetual statute." Thus, the Gemara reasoned, when wearing their proper priestly garments, priests were invested with their priesthood; but when they were not wearing their proper priestly garments, they lacked their priesthood and were considered like non-priests, who were liable to death if they performed the priestly service.[72]

A Midrash asked: As Exodus 29:9 reported that there already were 70 elders of Israel, why in Numbers 11:16, did God direct Moses to gather 70 elders of Israel? The Midrash deduced that when in Numbers 11:1, the people murmured, speaking evil, and God sent fire to devour part of the camp, all those earlier 70 elders had been burned up. The Midrash continued that the earlier 70 elders were consumed like Nadab and Abihu, because they too acted frivolously when (as reported in Exodus 24:11) they beheld God and inappropriately ate and drank. The Midrash taught that Nadab, Abihu, and the 70 elders deserved to die then, but because God so loved giving the Torah, God did not wish to create disturb that time.[73]

.jpg)

The Mishnah explained how the priests carried out the rites of the wave-offering described in Exodus 29:27: On the east side of the altar, the priest placed the two loaves on the two lambs and put his two hands beneath them and waved them forward and backward and upward and downward.[74]

The Sages interpreted the words of Exodus 29:27, "which is waved, and which is heaved up," to teach that the priest moved an offering forward and backward, upward and downward. As Exodus 29:27 thus compares "heaving" to "waving," the Midrash deduced that in every case where the priest waved, he also heaved.[75]

Rabbi Johanan deduced from the reference of Exodus 29:29 to "the holy garments of Aaron" that Numbers 31:6 refers to the priestly garments containing the Urim and Thummim when it reports that "Moses sent . . . Phinehas the son of Eleazar the priest, to the war, with the holy vessels." But the Midrash concluded that Numbers 31:6 refers to the Ark of the Covenant, to which Numbers 7:9 refers when it says, "the service of the holy things."[76]

A Baraita noted a difference in wording between Exodus 29:30, regarding the investiture of the High Priest, and Leviticus 16:32, regarding the qualifications for performing the Yom Kippur service. Exodus 29:29–30 says, "The holy garments of Aaron shall be for his sons after him, to be anointed in them, and to be consecrated in them. Seven days shall the son that is priest in his stead put them on." This text demonstrated that a priest who had put on the required larger number of garments and who had been anointed on each of the seven days was permitted to serve as High Priest. Leviticus 16:32, however, says, "And the priest who shall be anointed and who shall be consecrated to be priest in his father's stead shall make the atonement." The Baraita interpreted the words, "Who shall be anointed and who shall be consecrated," to mean one who had been anointed and consecrated in whatever way (as long as he had been consecrated, even if some detail of the ceremony had been omitted). The Baraita thus concluded that if the priest had put on the larger number of garments for only one day and had been anointed on each of the seven days, or if he had been anointed for only one day and had put on the larger number of garments for seven days, he would also be permitted to perform the Yom Kippur service. Noting that Exodus 29:30 indicated that the larger number of garments was necessary in the first instance for the seven days, the Gemara asked what Scriptural text supported the proposition that anointment on each of the seven days was in the first instance required. The Gemara answered that one could infer that from the fact that a special statement of the Torah was necessary to exclude it. Or, in the alternative, one could infer that from Exodus 29:29, which says, "And the holy garments of Aaron shall be for his sons after him, to be anointed in them, and to be consecrated in them." As Exodus 29:29 puts the anointing and the donning of the larger number of garments on the same level, therefor, just as the donning of the larger number of garments was required for seven days, so was the anointing obligatory for seven days.[77]

Rabbi Eliezer interpreted the words, "And there I will meet with the children of Israel; and [the Tabernacle] shall be sanctified by My glory," in Exodus 29:43 to mean that God would in the future meet the Israelites and be sanctified among them. The Midrash reports that this occurred on the eighth day of the consecration of the Tabernacle, as reported in Leviticus 9:1. And as Leviticus 9:24 reports, "when all the people saw, they shouted, and fell on their faces."[78]

The Mekhilta interpreted the words, "And there I will meet with the children of Israel; and it shall be sanctified by My glory," in Exodus 29:43 to be the words to which Moses referred in Leviticus 10:3, when he said, "This is it what the Lord spoke, saying: 'Through them who are near to Me I will be sanctified.'"[79]

The Gemara interpreted the report in Exodus 29:43 that the Tabernacle "shall be sanctified by My glory" to refer to the death of Nadab and Abihu. The Gemara taught that one should read not "My glory" (bi-khevodi) but "My honored ones" (bi-khevuday). The Gemara thus taught that God told Moses in Exodus 29:43 that God would sanctify the Tabernacle through the death of Nadab and Abihu, but Moses did not comprehend God's meaning until Nadab and Abihu died in Leviticus 10:2. When Aaron's sons died, Moses told Aaron in Leviticus 10:3 that Aaron's sons died only that God's glory might be sanctified through them. When Aaron thus perceived that his sons were God's honored ones, Aaron was silent, as Leviticus 10:3 reports, "And Aaron held his peace," and Aaron was rewarded for his silence.[80]

Joshua ben Levi interpreted the words of Exodus 29:46, "And they shall know that I am the Lord their God, Who brought them out of the land of Egypt in order that I may dwell among them," to teach that the Israelites came out of Egypt only because God foresaw that they would later build God a Tabernacle.[81]

.jpg)

Exodus chapter 30

.jpg)

Rabbi Jose argued that the dimensions of the inner altar in Exodus 30:2 helped to interpret the size of the outer altar. Rabbi Judah maintained that the outer altar was wider than Rabbi Jose thought it was, whereas Rabbi Jose maintained that the outer altar was taller than Rabbi Judah thought it was. Rabbi Jose said that one should read literally the words of Exodus 27:1, "five cubits long, and five cubits broad." But Rabbi Judah noted that Exodus 27:1 uses the word "square" (רָבוּעַ, ravua), just as Ezekiel 43:16 uses the word "square" (רָבוּעַ, ravua). Rabbi Judah argued that just as in Ezekiel 43:16, the dimension was measured from the center (so that the dimension described only one quadrant of the total), so the dimensions of Exodus 27:1 should be measured from the center (and thus, according to Rabbi Judah, the altar was 10 cubits on each side.) The Gemara explained that we know that this is how to understand Ezekiel 43:16 because Ezekiel 43:16 says, "And the hearth shall be 12 cubits long by 12 cubits broad, square," and Ezekiel 43:16 continues, "to the four sides thereof," teaching that the measurement was taken from the middle (interpreting "to" as intimating that from a particular point, there were 12 cubits in all directions, hence from the center). Rabbi Jose, however, reasoned that a common use of the word "square" applied to the height of the altar. Rabbi Judah said that one should read literally the words of Exodus 27:1, "And the height thereof shall be three cubits." But Rabbi Jose noted that Exodus 27:1 uses the word "square" (רָבוּעַ, ravua), just as Exodus 30:2 uses the word "square" (רָבוּעַ, ravua, referring to the inner altar). Rabbi Jose argued that just as in Exodus 30:2 the altar's height was twice its length, so too in Exodus 27:1, the height was to be read as twice its length (and thus the altar was 10 cubits high). Rabbi Judah questioned Rabbi Jose's conclusion, for if priests stood on the altar to perform the service 10 cubits above the ground, the people would see them from outside the courtyard. Rabbi Jose replied to Rabbi Judah that Numbers 4:26 states, "And the hangings of the court, and the screen for the door of the gate of the court, which is by the Tabernacle and by the altar round about," teaching that just as the Tabernacle was 10 cubits high, so was the altar 10 cubits high; and Exodus 38:14 says, "The hangings for the one side were fifteen cubits" (teaching that the walls of the courtyard were 15 cubits high). The Gemara explained that according to Rabbi Jose's reading, the words of Exodus 27:18, "And the height five cubits," meant from the upper edge of the altar to the top of the hangings. And according to Rabbi Jose, the words of Exodus 27:1, "and the height thereof shall be three cubits," meant that there were three cubits from the edge of the terrace (on the side of the altar) to the top of the altar. Rabbi Judah, however, granted that the priest could be seen outside the Tabernacle, but argued that the sacrifice in his hands could not be seen.[82]

The Mishnah taught that the incense offering of Exodus 30:7 was not subject to the penalty associated with eating invalidated offerings.[83]

In medieval Jewish interpretation

The parashah is discussed in these medieval Jewish sources:[84]

Exodus chapter 28

Interpreting Exodus 28:2, "And you shall make holy garments for Aaron your brother, for splendor and for beauty," Nachmanides taught that the High Priest's garments corresponded to the garments that monarchs wore when the Torah was given. Thus, Nachmanides taught that the "tunic of checker work" in Exodus 28:4 was a royal garment, like the one worn by David's daughter Tamar in 2 Samuel 13:18, "Now she had a garment of many colors upon her; for with such robes were the king's daughters that were virgins appareled." The miter in Exodus 28:4 was known among monarchs, as Ezekiel 21:31 notes with reference to the fall of the kingdom of Judah, "The miter shall be removed, and the crown taken off." Nachmanides taught that the ephod and the breastplate were also royal garments, and the plate that the High Priest wore around the forehead was like a monarch's crown. Finally, Nachmanides noted that the High Priest's garments were made of (in the words of Exodus 28:5) "gold," "blue-purple," and "red-purple," which were all symbolic of royalty.[85]

Maimonides taught that God selected priests for service in the Tabernacle in Exodus 28:41 and instituted the practice of sacrifices generally as transitional steps to wean the Israelites off of the worship of the times and move them toward prayer as the primary means of worship. Maimonides noted that in nature, God created animals that develop gradually. For example, when a mammal is born, it is extremely tender, and cannot eat dry food, so God provided breasts that yield milk to feed the young animal, until it can eat dry food. Similarly, Maimonides taught, God instituted many laws as temporary measures, as it would have been impossible for the Israelites suddenly to discontinue everything to which they had become accustomed. So God sent Moses to make the Israelites (in the words of Exodus 19:6) "a kingdom of priests and a holy nation." But the general custom of worship in those days was sacrificing animals in temples that contained idols. So God did not command the Israelites to give up those manners of service, but allowed them to continue. God transferred to God's service what had formerly served as a worship of idols, and commanded the Israelites to serve God in the same manner — namely, to build to a Sanctuary (Exodus 25:8), to erect the altar to God's name (Exodus 20:21), to offer sacrifices to God (Leviticus 1:2), to bow down to God, and to burn incense before God. God forbad doing any of these things to any other being and selected priests for the service in the temple in Exodus 28:41: "And they shall minister to me in the priest's office." By this Divine plan, God blotted out the traces of idolatry, and established the great principle of the Existence and Unity of God. But the sacrificial service, Maimonides taught, was not the primary object of God's commandments about sacrifice; rather, supplications, prayers, and similar kinds of worship are nearer to the primary object. Thus God limited sacrifice to only one temple (see Deuteronomy 12:26) and the priesthood to only the members of a particular family. These restrictions, Maimonides taught, served to limit sacrificial worship, and kept it within such bounds that God did not feel it necessary to abolish sacrificial service altogether. But in the Divine plan, prayer and supplication can be offered everywhere and by every person, as can be the wearing of tzitzit (Numbers 15:38) and tefillin (Exodus 13:9, 16) and similar kinds of service.[86]

In modern interpretation

The parashah is discussed in these modern sources:

Exodus chapter 27

The 20th century Reform Rabbi Gunther Plaut reported that after the Romans destroyed the Temple, Jews’ sought to honor the commandment in Exodus 27:20–21 to light the menorah by keeping a separate light, a ner tamid, in the synagogue. Originally Jews set the ner tamid opposite the ark on the synagogue’s western wall, but then moved it to a niche by the side of the ark and later to a lamp suspended above the ark. Plaut reported that the ner tamid has come to symbolize God's presence, a spiritual light emanating as if from the Temple.[87]

Exodus chapter 28

Noting that Exodus 28:1 first introduces Aaron and his family as “priests” without further defining the term, Plaut concluded that either the institution was already well known at the time (as the Egyptians and Midianites had priests) or that the story was retrojected back from a later time that had long known priests and their job. Scholars found the priestly garments unrealistic, complex, and extravagant, hardly befitting a wilderness setting. Plaut concluded, however, that while the text likely contains embellishments from later times, there is little reason to doubt that it also reports traditions going back to Israel’s earliest days.[88]

Reading in Exodus 28:2 the instruction to make holy garments for Aaron and his sons “for glory and for beauty,” the mid-20th-century Italian-Israeli scholar Umberto Cassuto, formerly of the Hebrew University of Jerusalem, explained that these were clothes that would indicate the degree of holiness in keeping with his high office.[89] Professor Nahum M. Sarna, formerly of Brandeis University, wrote that God ordained special attire for Aaron and his sons as insignia of office, so that the occupants of the sacred office could be distinguishable from the laity just as sacred space could be differentiated from profane space.[90] Reading “for glory and for beauty” in Exodus 28:2, Professor Richard Elliott Friedman of the University of Georgia argued that beauty is inspiring and valuable, and that religion is not the enemy of the senses.[91]

Sarna noted that Exodus 28 makes no mention of footwear, as the priests officiated barefoot.[92] Professor Carol Meyers of Duke University inferred that the priests wore no shoes on holy ground, noting that in Exodus 3:5, God told Moses to take off his shoes, for the place on which he stood was holy ground.[93]

Plaut reported that the priestly garments enumerated in Exodus 28:2–43 are the direct antecedents of those used today in the Catholic and Greek Orthodox Churches, whose priests — and especially bishops — wear similar robes when officiating. In the synagogue, the Torah scroll is similarly embellished and dressed in an embroidered mantle and crowned by pomegranates and bells.[88]

Noting that amid the description of the “glorious” priestly garments in Exodus 28:2–43 is the warning in Exodus 28:35 that Aaron might die, Professor Walter Brueggemann, formerly of Columbia Theological Seminary, wondered whether the text intends to convey the irony that one so well appointed was under threat of death. And Brueggemann noted that Exodus 25–31 proceeds to Exodus 32 (which he admitted came from a different textual tradition), and wondered whether the text means to convey that Aaron was seduced by his glorious adornment to act as he did in the incident of the Golden Calf. Brueggemann concluded that the affirmation and devastating critique of Aaron live close together in the text, teaching that the affirmation, the temptation, and the critique are inherent in the priesthood and the handler of holy things.[94]

Reading God’s command in Exodus 28:41 for Moses to anoint Aaron and his sons, Plaut reported that anointing was a common procedure in antiquity to induct priests or kings into office. Anointing oil symbolized wellbeing, and its daily use (especially in later Rome) was emblematic of the good life. The pouring of oil on the head signified having been favored by or set apart for the deity. Israelites chiefly used olive oil for ointments, Babylonians also used sesame oil and animal fats, and Egyptians used almond oil and animal fats.[95]

Commandments

According to Maimonides and Sefer ha-Chinuch, there are 4 positive and 3 negative commandments in the parashah:[96]

- To light the Menorah every day[97]

- The Kohanim must wear their priestly garments during service.[98]

- The breastpiece must not be loosened from the Ephod.[99]

- Not to tear the priestly garments[100]

- The Kohanim must eat the sacrificial meat.[101]

- To burn incense every day[102]

- Not to burn anything on the incense altar besides incense[103]

In the liturgy

The tamid sacrifice that Exodus 29:38–39 called for the priests to offer at twilight presaged the afternoon prayer service, called "Mincha" or "offering" in Hebrew.[104]

Haftarah

Generally

The haftarah for the parashah is Ezekiel 43:10–27.

Connection to the Parashah

Both the parashah and the haftarah in Ezekiel describe God's holy sacrificial altar and its consecration, the parashah in the Tabernacle in the wilderness,[105] and the haftarah in Ezekiel's conception of a future Temple.[106] Both the parashah and the haftarah describe plans conveyed by a mighty prophet, Moses in the parashah and Ezekiel in the haftarah.

On Shabbat Zachor

When Parashah Tetzaveh coincides with Shabbat Zachor (the special Sabbath immediately preceding Purim—as it does in 2013, 2015, 2017, 2018, and 2020), the haftarah is:

Connection to the Special Sabbath

On Shabbat Zachor, the Sabbath just before Purim, Jews read Deuteronomy 25:17–19, which instructs Jews: "Remember (זָכוֹר, zachor) what Amalek did" in attacking the Israelites.[107] The haftarah for Shabbat Zachor, 1 Samuel 15:2–34 or 1–34, describes Saul's encounter with Amalek and Saul's and Samuel's treatment of the Amalekite king Agag. Purim, in turn, commemorates the story of Esther (said to be a descendant of Saul in some rabbinic literature) and the Jewish people's victory over Haman's plan to kill the Jews, told in the book of Esther.[108] Esther 3:1 identifies Haman as an Agagite, and thus a descendant of Amalek. Numbers 24:7 identifies the Agagites with the Amalekites. Alternatively, a Midrash tells the story that between King Agag's capture by Saul and his killing by Samuel, Agag fathered a child, from whom Haman in turn descended.[109]

Notes

- ↑ "Torah Stats — Shemoth". Akhlah Inc. Retrieved July 6, 2013.

- ↑ "Parashat Tetzaveh". Hebcal. Retrieved February 5, 2015.

- ↑ See, e.g., The Schottenstein Edition Interlinear Chumash: Shemos/Exodus. Edited by Menachem Davis, pages 201–24. Brooklyn: Mesorah Publications, 2008. ISBN 1-4226-0204-4.

- ↑ Exodus 27:20–21.

- ↑ Exodus 28.

- ↑ Exodus 28:13–30.

- ↑ Exodus 28:30.

- ↑ Exodus 28:31–43.

- ↑ Exodus 33–35.

- ↑ Exodus 29.

- ↑ Exodus 29:10–12.

- ↑ Exodus 29:19–20.

- ↑ Exodus 29:42–45.

- ↑ Exodus 30.

- ↑ See, e.g., "A Complete Triennial Cycle for Reading the Torah" (PDF). The Jewish Theological Seminary. Retrieved June 16, 2014.

- ↑ For more on inner-Biblical interpretation, see, e.g., Benjamin D. Sommer. “Inner-biblical Interpretation.” In The Jewish Study Bible: Second Edition. Edited by Adele Berlin and Marc Zvi Brettler, pages 1835–41. New York: Oxford University Press, 2014. ISBN 978-0-19-997846-5.

- ↑ See generally Jon D. Levenson. "Cosmos and Microcosm." In Creation and the Persistence of Evil: The Jewish Drama of Divine Omnipotence, pages 78–99. San Francisco: Harper & Row, 1988. ISBN 0-06-254845-X. See also Jeffrey H. Tigay. “Exodus.” In The Jewish Study Bible: Second Edition. Edited by Adele Berlin and Marc Zvi Brettler, page 157.

- ↑ (1) Genesis 1:1–5; (2) 1:6–8; (3) 1:9–13; (4) 1:14–19; (5) 1:20–23; (6) 1:24–31; (7) Genesis 2:1–3.

- ↑ (1) Exodus 25:1–30:10; (2) 30:11–16; (3) 30:17–21; (4) 30:22–33; (5) 30:34–37; (6) 31:1–11; (7) 31:12–17.

- ↑ Genesis 2:1; Exodus 39:32.

- ↑ Genesis 1:31; Exodus 39:43.

- ↑ Genesis 2:2; Exodus 40:33–34.

- ↑ Genesis 2:3; Exodus 39:43.

- ↑ Genesis 2:3; Exodus 40:9–11.

- ↑ See generally Sorel Goldberg Loeb and Barbara Binder Kadden. Teaching Torah: A Treasury of Insights and Activities, page 157. Denver: A.R.E. Publishing, 1997. ISBN 0-86705-041-1.

- ↑ Jeffrey H. Tigay. “Exodus.” In The Jewish Study Bible: Second Edition. Edited by Adele Berlin and Marc Zvi Brettler, page 157.

- ↑ Exodus 25:37.

- ↑ Exodus 28:1–39.

- ↑ Compare Exodus 39:32 to Genesis 2:1–3; Exodus 39:43 to Genesis 1:31; and Exodus 40:33 to Genesis 2:2.

- ↑ Exodus 40:17.

- ↑ Carol Meyers. “Exodus.” In The New Oxford Annotated Bible: New Revised Standard Version With The Apocrypha: An Ecumenical Study Bible. Edited by Michael D. Coogan, Marc Z. Brettler, Carol A. Newsom, and Pheme Perkins, page 117. New York: Oxford University Press, Revised 4th Edition 2010. ISBN 0-19-528955-2.

- ↑ Note the similar language of Isaiah 61:10. See Walter Brueggemann. “The Book of Exodus.” In The New Interpreter's Bible. Edited by Leander E. Keck, volume 1, page 909. Nashville: Abingdon Press, 1994. ISBN 0-687-27814-7.

- ↑ For more on early nonrabbinic interpretation, see, e.g., Esther Eshel. “Early Nonrabbinic Interpretation.” In The Jewish Study Bible: Second Edition. Edited by Adele Berlin and Marc Zvi Brettler, pages 1841–59.

- ↑ Sirach 50:5–7.

- ↑ Exodus 28:6

- ↑ Josephus. Antiquities of the Jews book 3, chapter 7, paragraph 7. Circa 93–94. Reprinted in, e.g., The Works of Josephus: Complete and Unabridged, New Updated Edition. Translated by William Whiston, pages 90–91. Peabody, Massachusetts: Hendrickson Publishers, 1987. ISBN 0-913573-86-8.

- ↑ Philo. On the Life of Moses book 2, chapter 29, paragraphs 150–51. Alexandria, Egypt, early 1st century CE. Reprinted in, e.g., The Works of Philo: Complete and Unabridged, New Updated Edition. Translated by Charles Duke Yonge, page 504. Peabody, Massachusetts: Hendrickson Publishers, 1993. ISBN 0-943575-93-1.

- ↑ For more on classical rabbinic interpretation, see, e.g., Yaakov Elman. “Classical Rabbinic Interpretation.” In The Jewish Study Bible: Second Edition. Edited by Adele Berlin and Marc Zvi Brettler, pages 1859–78.

- ↑ Babylonian Talmud Yoma 3b. Babylonia, 6th century. Reprinted in, e.g., Koren Talmud Bavli: Yoma. Commentary by Adin Even-Israel (Steinsaltz), volume 9, page 12. Jerusalem: Koren Publishers, 2013. ISBN 978-965-301-570-8.

- ↑ Mishnah Menachot 8:5. Land of Israel, circa 200 CE. Reprinted in, e.g., The Mishnah: A New Translation. Translated by Jacob Neusner, page 750. New Haven: Yale University Press, 1988. ISBN 0-300-05022-4. Babylonian Talmud Menachot 86a.

- ↑ Mishnah Menachot 8:4. Reprinted in, e.g., The Mishnah: A New Translation. Translated by Jacob Neusner, page 749. Babylonian Talmud Menachot 86a.

- ↑ Mishnah Tamid 3:9. Reprinted in, e.g., The Mishnah: A New Translation. Translated by Jacob Neusner, page 867.

- ↑ Exodus Rabbah 33:4. 10th century. Reprinted in, e.g., Midrash Rabbah: Exodus. Translated by Simon M. Lehrman, volume 3, pages 416–18. London: Soncino Press, 1939. ISBN 0-900689-38-2.

- ↑ Exodus Rabbah 36:1. Reprinted in, e.g., Midrash Rabbah: Exodus. Translated by Simon M. Lehrman, volume 3, pages 436–38.

- ↑ Exodus Rabbah 36:2. Reprinted in, e.g., Midrash Rabbah: Exodus. Translated by Simon M. Lehrman, volume 3, pages 438–39.

- ↑ Exodus Rabbah 36:3. Reprinted in, e.g., Midrash Rabbah: Exodus. Translated by Simon M. Lehrman, volume 3, pages 439–40.

- ↑ Jerusalem Talmud Sukkah 29b. Land of Israel, circa 400 CE. Reprinted in, e.g., The Jerusalem Talmud: A Translation and Commentary. Edited by Jacob Neusner and translated by Jacob Neusner, Tzvee Zahavy, B. Barry Levy, and Edward Goldman. Peabody, Massachusetts: Hendrickson Publishers, 2009. ISBN 978-1-59856-528-7.

- 1 2 Babylonian Talmud Shabbat 21a. Reprinted in, e.g., Koren Talmud Bavli: Shabbat · Part One. Commentary by Adin Even-Israel (Steinsaltz), volume 2, page 100. Jerusalem: Koren Publishers, 2012. ISBN 978-965-301-564-7.

- ↑ Mishnah Sukkah 5:3. Reprinted in, e.g., The Mishnah: A New Translation. Translated by Jacob Neusner, page 289. Jerusalem Talmud Sukkah 29a. Reprinted in, e.g., The Jerusalem Talmud: A Translation and Commentary. Edited by Jacob Neusner and translated by Jacob Neusner, Tzvee Zahavy, B. Barry Levy, and Edward Goldman. Babylonian Talmud Sukkah 51a. Reprinted in, e.g., Koren Talmud Bavli: Sukka. Commentary by Adin Even-Israel (Steinsaltz), volume 10, page 252. Jerusalem: Koren Publishers, 2013. ISBN 978-965-301-571-5.

- ↑ Mishnah Avot 1:12. Reprinted in, e.g., The Mishnah: A New Translation. Translated by Jacob Neusner, page 674.

- ↑ Midrash Tanhuma, Shemot 27. 6th–7th centuries. Reprinted in, e.g., Metsudah Midrash Tanchuma. Translated and annotated by Avraham Davis; edited by Yaakov Y.H. Pupko, volume 3 (Shemos 1), pages 91–92. Monsey, New York: Eastern Book Press, 2006.

- ↑ Exodus Rabbah 37:2. Reprinted in, e.g., Midrash Rabbah: Exodus. Translated by Simon M. Lehrman, volume 3, pages 444–45.

- 1 2 3 Mishnah Yoma 7:5. Reprinted in, e.g., The Mishnah: A New Translation. Translated by Jacob Neusner, page 277. Babylonian Talmud Yoma 71b. Reprinted in, e.g., Koren Talmud Bavli: Yoma. Commentary by Adin Even-Israel (Steinsaltz), volume 9, page 351.

- ↑ Babylonian Talmud Shabbat 113b–14a. Reprinted in, e.g., Koren Talmud Bavli: Shabbat · Part Two. Commentary by Adin Even-Israel (Steinsaltz), volume 3, pages 175–76. Jerusalem: Koren Publishers, 2012. ISBN 978-965-301-565-4.

- ↑ Babylonian Talmud Yoma 72a–b. Reprinted in, e.g., Koren Talmud Bavli: Yoma. Commentary by Adin Even-Israel (Steinsaltz), volume 9, page 356.

- ↑ Leviticus Rabbah 10:6. Land of Israel, 5th century. Reprinted in, e.g., Midrash Rabbah: Leviticus. Translated by Harry Freedman and Maurice Simon, volume 4, pages 129–30. London: Soncino Press, 1939. ISBN 0-900689-38-2.

- ↑ Leviticus Rabbah 10:6. Reprinted in, e.g., Midrash Rabbah: Leviticus. Translated by Harry Freedman and Maurice Simon, volume 4, page 130.

- ↑ Babylonian Talmud Zevachim 35a.

- ↑ Babylonian Talmud Zevachim 88b. Reprinted in, e.g., Talmud Bavli. Elucidated by Israel Schneider, Yosef Widroff, Mendy Wachsman, Dovid Katz, Zev Meisels, and Feivel Wahl; edited by Yisroel Simcha Schorr and Chaim Malinowitz, volume 57, page 88b1. Brooklyn: Mesorah Publications, 1996. ISBN 1-57819-615-9.

- 1 2 Babylonian Talmud Yoma 72a. Reprinted in, e.g., Koren Talmud Bavli: Yoma. Commentary by Adin Even-Israel (Steinsaltz), volume 9, page 355.

- ↑ Babylonian Talmud Yoma 73b. Reprinted in, e.g., Koren Talmud Bavli: Yoma. Commentary by Adin Even-Israel (Steinsaltz), volume 9, page 363.

- ↑ Pirke De-Rabbi Eliezer, chapter 38. Early 9th century. Reprinted in, e.g., Pirke de Rabbi Eliezer. Translated and annotated by Gerald Friedlander, pages 295, 297–98. London, 1916. Reprinted New York: Hermon Press, 1970. ISBN 0-87203-183-7.

- ↑ Mishnah Sotah 9:12. Reprinted in, e.g., The Mishnah: A New Translation. Translated by Jacob Neusner, page 464. Babylonian Talmud Sotah 48a. Reprinted in, e.g., Talmud Bavli. Elucidated by Eliezer Herzka, Moshe Zev Einhorn, Michoel Weiner, Dovid Kamenetsky, and Reuvein Dowek; edited by Yisroel Simcha Schorr and Chaim Malinowitz, volume 33b, page 48a3. Brooklyn: Mesorah Publications, 2000. ISBN 1-57819-673-6.

- ↑ Babylonian Talmud Sotah 48b. Reprinted in, e.g., Talmud Bavli. Elucidated by Eliezer Herzka, Moshe Zev Einhorn, Michoel Weiner, Dovid Kamenetsky, and Reuvein Dowek; edited by Yisroel Simcha Schorr and Chaim Malinowitz, volume 33b, pages 48b1–2.

- ↑ Jerusalem Talmud Sotah 24b. Reprinted in, e.g., The Jerusalem Talmud: A Translation and Commentary. Edited by Jacob Neusner and translated by Jacob Neusner, Tzvee Zahavy, B. Barry Levy, and Edward Goldman.

- ↑ Babylonian Talmud Menachot 42b.

- ↑ Babylonian Talmud Yoma 72b. Reprinted in, e.g., Koren Talmud Bavli: Yoma. Commentary by Adin Even-Israel (Steinsaltz), volume 9, page 356.

- ↑ Babylonian Talmud Shabbat 63b. Reprinted in, e.g., Koren Talmud Bavli: Shabbat · Part One. Commentary by Adin Even-Israel (Steinsaltz), volume 2, page 308.

- ↑ Babylonian Talmud Yoma 12b. Reprinted in, e.g., Koren Talmud Bavli: Yoma. Commentary by Adin Even-Israel (Steinsaltz), volume 9, pages 53–54.

- ↑ Babylonian Talmud Niddah 13b.

- ↑ Babylonian Talmud Sanhedrin 83a.

- ↑ Babylonian Talmud Sanhedrin 83b.

- ↑ Midrash Tanhuma, Beha'aloscha 16. Reprinted in, e.g., Metsudah Midrash Tanchuma. Translated and annotated by Avraham Davis; edited by Yaakov Y.H. Pupko, volume 6 (Bamidbar 1), page 252–53.

- ↑ Mishnah Menachot 5:6. Reprinted in, e.g., The Mishnah: A New Translation. Translated by Jacob Neusner, page 743. Babylonian Talmud Menachot 61a.

- ↑ Numbers Rabbah 9:38. 12th century. Reprinted in, e.g., Midrash Rabbah: Numbers. Translated by Judah J. Slotki, volume 5, pages 313–14. London: Soncino Press, 1939. ISBN 0-900689-38-2. See also Numbers Rabbah 10:23. Reprinted in, e.g., Midrash Rabbah: Numbers. Translated by Judah J. Slotki, volume 5, page 403.

- ↑ Numbers Rabbah 22:4. Reprinted in, e.g., Midrash Rabbah: Numbers. Translated by Judah J. Slotki, volume 6, pages 855–56.

- ↑ Babylonian Talmud Yoma 5a. Reprinted in, e.g., Talmud Bavli. Elucidated by Abba Zvi Naiman, Michoel Weiner, Yosef Widroff, Moshe Zev Einhorn, Israel Schneider, and Zev Meisels; edited by Yisroel Simcha Schorr and Chaim Malinowitz, volume 13, page 5a2. Brooklyn: Mesorah Publications, 1998. ISBN 1-57819-660-4.

- ↑ Numbers Rabbah 14:21. Reprinted in, e.g., Midrash Rabbah: Numbers. Translated by Judah J. Slotki.

- ↑ Mekhilta of Rabbi Ishmael Pisha chapter 12. Land of Israel, late 4th century. Reprinted in, e.g., Mekhilta According to Rabbi Ishmael. Translated by Jacob Z. Lauterbach, volume 1, page 63. Philadelphia: Jewish Publication Society, 1933, reissued 2004. ISBN 0-8276-0678-8.

- ↑ Babylonian Talmud Zevachim 115b.

- ↑ Numbers Rabbah 3:6. Reprinted in, e.g., Midrash Rabbah: Numbers. Translated by Judah J. Slotki. See also Numbers Rabbah 12:6. Reprinted in, e.g., Midrash Rabbah: Numbers. Translated by Judah J. Slotki.

- ↑ Babylonian Talmud Zevachim 59b–60a. Reprinted in, e.g., Talmud Bavli. Elucidated by Moshe Zev Einhorn, Henoch Moshe Levin, Michoel Weiner, Shlomo Fox-Ashrei, and Abba Zvi Naiman; edited by Yisroel Simcha Schorr and Chaim Malinowitz, volume 56, pages 59b1–60a1. Brooklyn: Mesorah Publications, 1995. ISBN 1-57819-614-0.

- ↑ Mishnah Zevachim 4:3. Reprinted in, e.g., The Mishnah: A New Translation. Translated by Jacob Neusner, page 705. Babylonian Talmud Zevachim 42b.

- ↑ For more on medieval Jewish interpretation, see, e.g., Barry D. Walfish. “Medieval Jewish Interpretation.” In The Jewish Study Bible: Second Edition. Edited by Adele Berlin and Marc Zvi Brettler, pages 1891–1915.

- ↑ Nachmanides. Commentary on the Torah. Jerusalem, circa 1270. Reprinted in, e.g., Ramban (Nachmanides): Commentary on the Torah: Exodus. Translated by Charles B. Chavel, volume 2, pages 475–76. New York: Shilo Publishing House, 1973. ISBN 0-88328-007-8.

- ↑ Maimonides. The Guide for the Perplexed, part 3, chapter 32. Cairo, Egypt, 1190. Reprinted in, e.g., Moses Maimonides. The Guide for the Perplexed. Translated by Michael Friedländer, pages 322–27. New York: Dover Publications, 1956. ISBN 0-486-20351-4.

- ↑ W. Gunther Plaut. The Torah: A Modern Commentary: Revised Edition. Revised edition edited by David E.S. Stern, page 573. New York: Union for Reform Judaism, 2006. ISBN 0-8074-0883-2.

- 1 2 W. Gunther Plaut. The Torah: A Modern Commentary: Revised Edition. Revised edition edited by David E.S. Stern, page 561.

- ↑ Umberto Cassuto. A Commentary on the Book of Exodus. Jerusalem, 1951. Translated by Israel Abrahams, page 371. Jerusalem: The Magnes Press, The Hebrew University, 1967.

- ↑ Nahum M. Sarna. The JPS Torah Commentary: Exodus: The Traditional Hebrew Text with the New JPS Translation, page 176. Philadelphia: Jewish Publication Society, 1991. ISBN 0-8276-0327-4.

- ↑ Richard Elliott Friedman. Commentary on the Torah: With a New English Translation, page 266. New York: Harper San Francisco, 2001. ISBN 0-06-062561-9.

- ↑ Nahum M. Sarna. The JPS Torah Commentary: Exodus: The Traditional Hebrew Text with the New JPS Translation, page 177.

- ↑ The Torah: A Women's Commentary. Edited by Tamara Cohn Eskenazi and Andrea L. Weiss, page 477. New York: Women of Reform Judaism/URJ Press, 2008. ISBN 978-0-8074-1081-3.

- ↑ Walter Brueggemann. “The Book of Exodus.” In The New Interpreter's Bible. Edited by Leander E. Keck, volume 1, page 908.

- ↑ W. Gunther Plaut. The Torah: A Modern Commentary: Revised Edition. Revised edition edited by David E.S. Stern, page 567.

- ↑ See, e.g., Maimonides. The Commandments: Sefer Ha-Mitzvoth of Maimonides. Translated by Charles B. Chavel, volume 1, pages 34–35, 37, 42–43, 101–02; volume 2, pages 81, 85–86. London: Soncino Press, 1967. ISBN 0-900689-71-4. Sefer HaHinnuch: The Book of [Mitzvah] Education. Translated by Charles Wengrov, volume 1, pages 377–95. Jerusalem: Feldheim Publishers, 1991. ISBN 0-87306-179-9.

- ↑ Exodus 27:21.

- ↑ Exodus 28:2.

- ↑ Exodus 28:28.

- ↑ Exodus 28:32.

- ↑ Exodus 29:33.

- ↑ Exodus 30:7.

- ↑ Exodus 30:9.

- ↑ Babylonian Talmud Berakhot 26b. Reuven Hammer, Or Hadash: A Commentary on Siddur Sim Shalom for Shabbat and Festivals, page 1. New York: The Rabbinical Assembly, 2003. ISBN 0-916219-20-8.

- ↑ Exodus 27:1–8; 29:36–37.

- ↑ Ezekiel 43:13–17.

- ↑ Deuteronomy 25:17.

- ↑ Esther 1:1–10:3.

- ↑ Seder Eliyahu Rabbah, chapter 20. 10th century. Reprinted in, e.g., Tanna Debe Eliyyahu: The Lore of the School of Elijah. Translated by William G. Braude and Israel J. Kapstein. Philadelphia: Jewish Publication Society, 1981. ISBN 0-8276-0634-6. Targum Sheni to Esther 4:13.

Further reading

The parashah has parallels or is discussed in these sources:

Biblical

- Exodus 39:1–31 (making the priests' vestments).

- Leviticus 6:3 (priest wearing linen); 16:4–33 (high priest wearing linen).

- Deuteronomy 22:11 (combining wool and linen).

- 1 Samuel 2:18 (priest wearing linen); 22:18 (priests wearing linen).

- 2 Samuel 6:14 (David wearing linen in worship).

- Ezekiel 10:76 (holy man clad in linen); 44:17–18 (priests wearing linen).

- Daniel 10:5 (holy man clad in linen); 12:6–7 (holy man clad in linen).

- Psalms 29:2 (holiness of God); 77:21 (Moses and Aaron); 93:5 (holiness of God); 99:6 (Moses and Aaron); 106:16 (Moses and Aaron); 115:10,12 (house of Aaron); 118:3 (house of Aaron); 133:2 (anointing Aaron).

- 1 Chronicles 15:27 (David and Levites wearing linen in worship).

- 2 Chronicles 5:12 (Levites wearing linen in worship).

Early nonrabbinic

- Philo. Allegorical Interpretation 1: 26:81; 3: 40:118; On the Migration of Abraham 18:103; On the Life of Moses 2:29:150–51; The Special Laws 1:51:276. Alexandria, Egypt, early 1st Century C.E. Reprinted in, e.g., The Works of Philo: Complete and Unabridged, New Updated Edition. Translated by Charles Duke Yonge, 34, 63, 263, 504, 560. Peabody, Massachusetts: Hendrickson Publishers, 1993. ISBN 0-943575-93-1.

- Josephus. The Wars of the Jews, 5:5:7. Circa 75 C.E. Reprinted in, e.g., The Works of Josephus: Complete and Unabridged, New Updated Edition. Translated by William Whiston, 708. Peabody, Massachusetts: Hendrickson Publishers, 1987. ISBN 0-913573-86-8.

- Josephus, Antiquities of the Jews 3:6:1–3:10:1. Circa 93–94. Reprinted in, e.g., The Works of Josephus: Complete and Unabridged, New Updated Edition. Translated by William Whiston, 85–95. Peabody, Massachusetts: Hendrickson Publishers, 1987. ISBN 0-913573-86-8.

Classical rabbinic

- Mishnah: Yoma 7:5; Sukkah 5:3; Sotah 9:12; Zevachim 4:3; Menachot 5:6, 8:4–5; Keritot 1:1; Tamid 3:9, 7:1; Kinnim 3:6. Land of Israel, circa 200 C.E. Reprinted in, e.g., The Mishnah: A New Translation. Translated by Jacob Neusner, pages 277, 289, 464, 705, 743, 749–50, 867, 871, 889. New Haven: Yale University Press, 1988. ISBN 0-300-05022-4.

- Tosefta: Sotah 7:17; Menachot 6:11, 7:6, 9:16. Land of Israel, circa 300 C.E. Reprinted in, e.g., The Tosefta: Translated from the Hebrew, with a New Introduction. Translated by Jacob Neusner, volume 1, page 865; volume 2, pages 1430–31, 1435, 1448. Peabody, Massachusetts: Hendrickson Publishers, 2002. ISBN 1-56563-642-2.

- Jerusalem Talmud: Challah 20a; Shabbat 20b; Pesachim 35a, 57a, 62a; Yoma 3a, 5a, 6b, 8b, 14a–15a, 16a, 20a–b, 21b, 36a–b, 49b–50a; Sukkah 29b; Megillah 17a; Sotah 24b. Land of Israel, circa 400 CE. Reprinted in, e.g., Talmud Yerushalmi. Edited by Chaim Malinowitz, Yisroel Simcha Schorr, and Mordechai Marcus, volumes 11, 13, 18–19, 21–22, 26. Brooklyn: Mesorah Publications, 2008–2013. And reprinted in The Jerusalem Talmud: A Translation and Commentary. Edited by Jacob Neusner and translated by Jacob Neusner, Tzvee Zahavy, B. Barry Levy, and Edward Goldman. Peabody, Massachusetts: Hendrickson Publishers, 2009. ISBN 978-1-59856-528-7.

.jpg)

- Babylonian Talmud: Shabbat 12a, 21a, 31a, 63b; Eruvin 4a; Pesachim 16b, 24a, 59a–b, 72b, 77a, 92a; Yoma 5a–b, 7a–b, 14a–b, 15a, 31b, 33a–b, 45b, 52b, 57b, 58b, 61a, 68b, 71b–72b; Sukkah 5a, 37b, 49b; Taanit 11b; Megillah 12a–b, 29b; Chagigah 26b; Yevamot 40a, 60b, 68b, 87a, 90a; Nedarim 10b; Nazir 47b; Sotah 9b, 36a, 38a, 48a–b; Gittin 20a–b; Bava Batra 8b, 106b; Sanhedrin 12b, 34b, 61b, 83a–b, 106a; Makkot 13a, 17a, 18a–b; Shevuot 8b, 9b–10b, 14a; Avodah Zarah 10b, 23b, 39a; Zevachim 12b, 17b, 19a, 22b–23a, 24b, 26a, 28b, 44b, 45b, 59b, 83b, 87a, 88a–b, 95a, 97b, 112b, 115b, 119b; Menachot 6a, 11a, 12b, 14b, 25a, 29a, 36b, 42b, 49a, 50a–51a, 61a, 73a, 83a, 86a–b, 89a, 98b; Chullin 7a, 138a; Arakhin 3b–4a, 16a; Keritot 5a; Meilah 11b, 17b; Niddah 13b. Babylonia, 6th Century. Reprinted in, e.g., Talmud Bavli. Edited by Yisroel Simcha Schorr, Chaim Malinowitz, and Mordechai Marcus, 72 volumes. Brooklyn: Mesorah Pubs., 2006.

Medieval

- Bede. Of the Tabernacle and Its Vessels, and of the Priestly Vestments. Monkwearmouth, England, 720s. Reprinted in Bede: On the Tabernacle. Translated with notes and introduction by Arthur G. Holder. Liverpool: Liverpool University Press, 1994. ISBN 0-85323-378-0.

- Exodus Rabbah 36:1–38:9. 10th Century. Reprinted in, e.g., Midrash Rabbah: Exodus. Translated by Simon M. Lehrman, volume 3, pages 436–57. London: Soncino Press, 1939. ISBN 0-900689-38-2.

- Saadia Gaon. The Book of Beliefs and Opinions, 2:11; 3:10. Baghdad, Babylonia, 933. Translated by Samuel Rosenblatt, 125, 177. New Haven: Yale Univ. Press, 1948. ISBN 0-300-04490-9.

- Rashi. Commentary. Exodus 27–30. Troyes, France, late 11th Century. Reprinted in, e.g., Rashi. The Torah: With Rashi's Commentary Translated, Annotated, and Elucidated. Translated and annotated by Yisrael Isser Zvi Herczeg, 2:375–421. Brooklyn: Mesorah Publications, 1994. ISBN 0-89906-027-7.

- Rashbam. Commentary on the Torah. Troyes, early 12th century. Reprinted in, e.g., Rashbam's Commentary on Exodus: An Annotated Translation. Edited and translated by Martin I. Lockshin, pages 351–84. Atlanta: Scholars Press, 1997. ISBN 0-7885-0225-5.

- Abraham ibn Ezra. Commentary on the Torah. France, 1153. Reprinted in, e.g., Ibn Ezra's Commentary on the Pentateuch: Exodus (Shemot). Translated and annotated by H. Norman Strickman and Arthur M. Silver, volume 2, pages 583–628. New York: Menorah Publishing Company, 1996. ISBN 0-932232-08-6.

- Maimonides. Guide for the Perplexed, part 1, chapter 25; part 3, chapters 4, 32, 45, 46, 47. Cairo, Egypt, 1190. Reprinted in, e.g., Moses Maimonides. The Guide for the Perplexed. Translated by Michael Friedländer, pages 34, 257, 323, 357, 362, 369. New York: Dover Publications, 1956. ISBN 0-486-20351-4.

- Hezekiah ben Manoah. Hizkuni. France, circa 1240. Reprinted in, e.g., Chizkiyahu ben Manoach. Chizkuni: Torah Commentary. Translated and annotated by Eliyahu Munk, volume 2, pages 595–610. Jerusalem: Ktav Publishers, 2013. ISBN 978-1-60280-261-2.

- Nachmanides. Commentary on the Torah. Jerusalem, circa 1270. Reprinted in, e.g., Ramban (Nachmanides): Commentary on the Torah. Translated by Charles B. Chavel, volume 2, pages 471–509. New York: Shilo Publishing House, 1973. ISBN 0-88328-007-8.

- Zohar 2:179b–187b. Spain, late 13th Century. Reprinted in, e.g., The Zohar. Translated by Harry Sperling and Maurice Simon. 5 volumes. London: Soncino Press, 1934.

- Bahya ben Asher. Commentary on the Torah. Spain, early 14th century. Reprinted in, e.g., Midrash Rabbeinu Bachya: Torah Commentary by Rabbi Bachya ben Asher. Translated and annotated by Eliyahu Munk, volume 4, pages 1276–310. Jerusalem: Lambda Publishers, 2003. ISBN 965-7108-45-4.

- Jacob ben Asher (Baal Ha-Turim). Commentary on the Torah. Early 14th century. Reprinted in, e.g., Baal Haturim Chumash: Shemos/Exodus. Translated by Eliyahu Touger; edited and annotated by Avie Gold, volume 2, pages 845–79. Brooklyn: Mesorah Publications, 2000. ISBN 1-57819-129-7.

- Isaac ben Moses Arama. Akedat Yizhak (The Binding of Isaac). Late 15th century. Reprinted in, e.g., Yitzchak Arama. Akeydat Yitzchak: Commentary of Rabbi Yitzchak Arama on the Torah. Translated and condensed by Eliyahu Munk, volume 1, pages 471–83. New York, Lambda Publishers, 2001. ISBN 965-7108-30-6.

Modern

- Abraham Saba. Ẓeror ha-Mor (Bundle of Myrrh). Fez, Morocco, circa 1500. Reprinted in, e.g., Tzror Hamor: Torah Commentary by Rabbi Avraham Sabba. Translated and annotated by Eliyahu Munk, volume 3, pages 1123–46. Jerusalem, Lambda Publishers, 2008. ISBN 978-965-524-013-9.

- Obadiah ben Jacob Sforno. Commentary on the Torah. Venice, 1567. Reprinted in, e.g., Sforno: Commentary on the Torah. Translation and explanatory notes by Raphael Pelcovitz, pages 432–43. Brooklyn: Mesorah Publications, 1997. ISBN 0-89906-268-7.

- Moshe Alshich. Commentary on the Torah. Safed, circa 1593. Reprinted in, e.g., Moshe Alshich. Midrash of Rabbi Moshe Alshich on the Torah. Translated and annotated by Eliyahu Munk, volume 2, pages 551–62. New York, Lambda Publishers, 2000. ISBN 965-7108-13-6.