Tar-Baby

The Tar-Baby is the second of the Uncle Remus stories published in 1881; it is about a doll made of tar and turpentine used by the villainous Br'er Fox to entrap Br'er Rabbit. The more that Br'er Rabbit fights the Tar-Baby, the more entangled he becomes.

In modern usage, "tar baby" refers to any "sticky situation" that is only aggravated by additional involvement with it.

Story

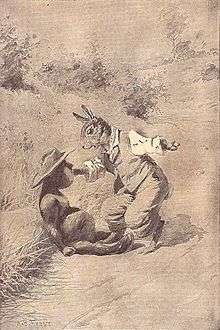

In one tale, Br'er Fox constructs a doll out of a lump of tar and dresses it with some clothes. When Br'er Rabbit comes along, he addresses the tar "baby" amiably, but receives no response. Br'er Rabbit becomes offended by what he perceives as the Tar-Baby's lack of manners, punches it and, in doing so, becomes stuck. The more Br'er Rabbit punches and kicks the tar "baby" out of rage, the worse he gets stuck.

Now that Br'er Rabbit is stuck, Br'er Fox ponders how to dispose of him. The helpless but cunning Br'er Rabbit pleads, "Do anything you want with me --- roas' me, hang me, skin me, drown me --- but please, Br'er Fox, don't fling me in dat brier-patch," prompting the sadistic Br'er Fox to do exactly that because he gullibly believes it will inflict maximum pain on Br'er Rabbit. As rabbits are at home in thickets, however, the resourceful Br'er Rabbit escapes.

The story was originally published in Harper's Weekly by Robert Roosevelt; years later Joel Chandler Harris wrote of the Tar-Baby in his Uncle Remus stories.

Related stories

Variations on the tar baby legend are found in the folklore of more than one culture. In the Journal of American Folklore, Aurelio M. Espinosa examined 267 versions of the tar baby story.[1] The next year, Archer Taylor added a list of tarbaby stories from more sources around the world, citing scholarly claims of its earliest origins in India and Iran.[2] Espinosa later published documentation on tarbaby stories from a variety of language communities around the world.[3]

A very similar West African tale is told of the mythical hero Anansi the Spider. In this version it is Anansi who creates a wooden doll and covers it over with gum, then puts a plate of yams in its lap, in order to capture the she-fairy Mmoatia (sometimes described as an "elf" or "dwarf"). Mmoatia takes the bait and eats the yams, but grows angry when the doll does not respond and strikes it, becoming stuck in the process.

In a variant recorded in Jamaica, Anansi himself was once similarly trapped with a tar-baby made by the eldest son of Mrs. Anansi, after Anansi pretended to be dead in order to steal her peas.[4] In a Spanish language version told in the mountainous parts of Colombia, an unnamed rabbit is trapped by the "Muñeco de Brea" (tar doll). A Buddhist myth tells of Prince Five-weapons (the Future Buddha) who encounters the ogre Sticky-Hair in a forest.[5][6][7]

The tar baby theme is present in the folklore of various tribes of Meso-America and of South America: it is found in such stories[8] as the Nahuatl (of Mexico) "Lazy Boy and Little Rabbit" (González Casanova 1946, pp. 55–67), Pipil (of El Salvador) "Rabbit and Little Fox" (Schultes 1977, pp. 113–116), and Palenquero (of Colombia) "Rabbit, Toad, and Tiger" (Patiño Rosselli 1983, pp. 224–229). In Mexico, the tar baby story is also found among Mixtec[9] Zapotec,[10] and Popoluca.[11][12] In North America, the tale appears in White Mountain Apache lore as "Coyote Fights a Lump of Pitch".[13] In this story, white men are said to have erected the pitch-man that ensnares Coyote.

According to James Mooney in "Myths of the Cherokee",[14] the tar baby story may have been influenced in America by the Cherokee "Tar Wolf" story, considered unlikely to have been derived from similar African stories: "Some of these animal stories are common to widely separated [Native American] tribes among whom there can be no suspicion of [African] influences. Thus the famous "tar baby" story has variants, not only among the Cherokee, but also in New Mexico, Washington [State], and southern Alaska—wherever, in fact, the pine supplies enough gum to be molded into a ball for [Native American] uses...".

In the Tar Wolf story, the animals were thirsty during a dry spell, and agreed to dig a well. The lazy rabbit refused to help dig, and so had no right to drink from the well. But she was thirsty, and stole from the well at night. The other animals fashioned a wolf out of tar and placed it near the well to scare the thief. The rabbit was scared at first, but when the tar wolf did not respond to her questions, she struck it and was held fast. Then she struggled with it and became so ensnared that she couldn't move. The next morning, the animals discovered the rabbit and proposed various ways of killing her, such as cutting her head off, and the rabbit responded to each idea saying that it would not harm her. Then an animal suggested throwing the rabbit into the thicket to die. At this, the rabbit protested vigorously and pleaded for her life. The animals threw the rabbit into the thicket. The rabbit then gave a whoop and bounded away, calling out to the other animals "This is where I live!".

Popular culture

Walt Disney Studios released Song of the South, which contains the Tar-Baby story, in 1946. The film was never released on VHS or DVD in North America due to concerns about racially insensitive content. The ride Splash Mountain, which is in three of the Walt Disney theme parks, is based on the stories by Uncle Remus. However, instead of the Tar-Baby, Br'er Rabbit is captured in a beehive.

The Tar-Baby appears in the Toontown countryside in Who Framed Roger Rabbit and was featured as one of the guests in House of Mouse.

"Lollipop and the Tar Baby" is a 1977 science fiction short story by John Varley, taking place in the lonely space at the edge of the Solar System and part of this writer's far-future "Eight Worlds" universe. It is not a simple re-telling of the original tale, but undertones of it appear in the way in which the story's protagonist finally resolves her predicament.

In Hollywood's Roots 2016 miniseries, which is given a contemporary perspective, a group of white men order Kunta Kinte to hand over his infant daughter Kizzy, referring to her by the historically inaccurate (thus historical revisionist) term "tar baby." (See Racist interpretation below)

Idiomatic references

The story has given rise to two American English idioms. References to Br'er Rabbit's feigned protestations such as "please don't fling me in dat brier-patch" refer to guilefully seeking something by pretending to protest, with a "briar patch" often meaning a more advantageous situation or environment for one of the parties. The term "tar baby" has come to refer to a problem that is exacerbated by attempts to struggle with it, or by extension a situation in which mere contact can lead to becoming inextricably involved.

Racist interpretation

Although the term's provenance rests in African folklore (i.e., the gum doll Anansi created to trap Mmoatia), some Americans consider "tar baby" to be a pejorative term for African Americans.[15] The Oxford English Dictionary defines "tar baby" as "a difficult problem which is only aggravated by attempts to solve it",[16] but the online subscription-only version adds a second definition: "a derogatory term for a Black (U.S.) or a Maori (N.Z.)".[17][18]

Several United States politicians—including presidential candidates John Kerry, John McCain, Michele Bachmann, and Mitt Romney—have been criticized by civil rights leaders, the media, and fellow politicians for using the "tar baby" metaphor.[18][19] An article in The New Republic argued that people are "unaware that some consider it to have a second meaning as a slur" and it "is an obscure slur, not even known to be so by a substantial proportion of the population." It continued that, "those who feel that tar baby's status as a slur is patently obvious are judging from the fact that it sounds like a racial slur".[20]

In other countries, the phrase continues to refer to problems worsened by intervention.[21]

See also

References

- ↑ Espinosa, A. (1943). A new classification of the fundamental elements of the tar-baby story on the basis of two hundred and sixty-seven versions. Journal of American Folklore, 56, pp. 31–37 as cited in Campbell, J. (1949). The Hero with a Thousand Faces. New York, New York: MJF Books, 87. ISBN 1-56731-120-2.

- ↑ 1944. The Tarbaby Once More. Journal of the American Oriental Society Vol. 64, No. 1 pp. 4–7.

- ↑ pp. 58–60. Aurelio Macedonio Espinosa. 1990. The Folklore of Spain in the American Southwest: Traditional Spanish Folk Literature in Northern New Mexico and Southern Colorado. Norman: University of Oklahoma Press.

- ↑ ""Anansi and the Tar-baby", Jamaican Anansi Stories". Sacred-texts.com. 1924. Retrieved 2010-07-03.

- ↑ Campbell, J. (1949). The Hero with a Thousand Faces. New York, New York: MJF Books, pp. 85–89.

- ↑ Pilpay (2008). Charles Dudley Warner, ed. "A Library of the World's Best Literature – Ancient and Modern – Vol. XXIX". Cosimo, Inc. pp. 11460–11463. ISBN 9781605202235.

- ↑ Eugene Watson Burlingame, ed. (1994). "Buddhist Parables". Mortilal Banarsidass. pp. 41–44. ISBN 8120807383.

- ↑ Enrique Margery: "The Tar-Baby Motif", p. 9. In :- Latin American Indian Literatures Journal, Vol. 6 (1990), pp. 1–13

- ↑ Dyk, Anne, ed. 1959. "Tarbaby. Mixteco texts, pp. 33–44. (Linguistic Series 3.) Norman: Summer Institute of Linguistics of the University of Oklahoma.

- ↑ Stubblefield, Carol and Morris Stubblefield, compilers. 1994. Rabbit and Coyote. Mitla Zapotec texts, pp. 61–102. (Folklore texts in Mexican Indian languages no. 3. Language Data, Amerindian Series 12.) Dallas: Summer Institute of Linguistics.

- ↑ Clark, Lawrence E. 1961. Rabbit and Coyote. Sayula Popoluca texts, with grammatical outline, pp. 147–175. (Linguistic Series 6.) Norman: Summer Institute of Linguistics of the University of Oklahoma.

- ↑ Foster, George McClelland. Sierra popoluca folklore and beliefs. Vol. 42. University of California press, 1945.

- ↑ Richard Erdoes and Alfonso Ortiz, eds. 1984. In American Indian Myths and Legends, pp. 359–361. New York: Pantheon.

- ↑ James Mooney, "Myths of the Cherokee", Dover 1995, pp. 271–273, 232–236, 450. Reprinted from a Government Printing Office publication of 1900. Also, Cherokee tarbaby story

- ↑ Romney Apologizes For 'Tar Baby', 2006-07-31.

- ↑ "tar, n.1". April 2012. Oxford University Press. Retrieved: 2012-04-20.

- ↑ "tar, n.1". OED Online. December 2011. Oxford University Press. Retrieved: 2012-01-12.

- 1 2 Coates, Ta-Neishi Paul (August 1, 2006). "Why 'Tar Baby' Is Such a Sticky Phrase". Time.

- ↑

- White House Press Briefing, 2006-05-16.

- Washington at Work; The Senator Pursues 'Untold' M.I.A. Story, New York Times, Barbara Crossette, 1992-08-10.

- "Spokeswoman: Bachmann 'Tar Baby' Quote Not Racial". ABC News. April 20, 2012.

- Creators.com.

- "Click2Houston.com". Click2Houston.com. 2005-10-05. Retrieved 2010-07-03.

- Raised on point of order, Debates, House of Commons, Ottawa, Canada, Conservative MP, Pierre Poilievre, uses the term twice answering separate questions during Question Period. 2009-05-29.

- "Full Interview 630 KHOW Audio Version". Khow.com. 2011-07-29. Retrieved 2011-08-19.

- "Rep. Lamborn likens Obama to a "tar baby"". Salon.com. 2011-08-01. Retrieved 2016-02-20.

- "GOP Congressman, Doug Lamborn of Colorado, blasted for likening President Obama to a 'tar baby' New York Daily News". Nydailynews.com. 2011-08-02. Retrieved 2011-08-19.

- ↑ McWhorter: 'Tar Baby' Isn't Actually a Racist Slur The New Republic, 2011-08-03.

- ↑ Solar panels burn taxpayer dollars The Australian, 2011-05-23.

Further reading

-

Media related to Tar baby at Wikimedia Commons

Media related to Tar baby at Wikimedia Commons -

The dictionary definition of tarbaby at Wiktionary

The dictionary definition of tarbaby at Wiktionary -

Works related to Uncle Remus: His Songs and His Sayings/The Wonderful Tar-Baby Story at Wikisource

Works related to Uncle Remus: His Songs and His Sayings/The Wonderful Tar-Baby Story at Wikisource - González Casanova, Pablo (1946) : Cuentos indígenas.

- Schultze Jena, Leonhard (1977) : Mito y Leyendas de los Pipiles de Izalco. El Salvador : Ediciones Cuscatlán.

- Patiño Rosselli, Carlos (1983) : Lengua y sociedad en el Panlenque de San Basilio. Bogotá : Instituto Caro y Cuervo.