Negro

Negro (plural Negroes) is a term traditionally used to denote persons of Negroid heritage. It has various equivalents in other languages.

In English

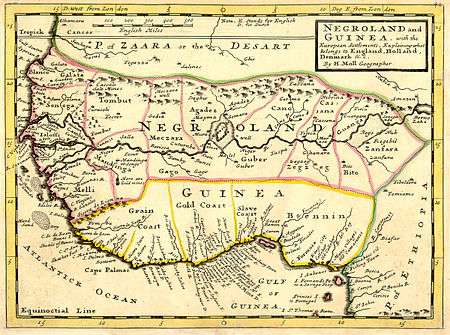

Around 1442, the Portuguese first arrived in Southern Africa while trying to find a sea route to India. The term negro, literally meaning 'black', was used by the Spanish and Portuguese as a simple description to refer to the Bantu peoples that they encountered. Negro denotes "black" in Spanish and Portuguese, derived from the Latin word niger, meaning black, which itself is probably from a Proto-Indo-European root *nekw-, "to be dark", akin to *nokw-, night.[1][2] "Negro" was also used of the peoples of West Africa in old maps labelled Negroland, an area stretching along the Niger River.

From the 18th century to the late 1960s, negro (later capitalized) was considered to be the proper English-language term for people of black African origin. According to Oxford Dictionaries, use of the word "now seems out of date or even offensive in both British and US English".[3]

A specifically female form of the word, negress (sometimes capitalized), was occasionally used. However, like Jewess, it has all but completely fallen from use.

Negroid has traditionally been used within physical anthropology to denote one of the three purported races of humankind, alongside Caucasoid and Mongoloid. The suffix -oid means "similar to". "Negroid" as a noun was used to designate a wider or more generalized category than Negro; as an adjective, it qualified a noun as in, for example, "negroid features".[4]

United States

Negro superseded colored as the most polite word for African Americans at a time when black was considered more offensive.[5] In Colonial America during the 1600s the term Negro was, according to one historian, also used to describe Native Americans[6] The American Negro Academy was founded in 1897, to support liberal arts education. Marcus Garvey used the word in the names of black nationalist and pan-Africanist organizations such as the Universal Negro Improvement Association (founded 1914), the Negro World (1918), the Negro Factories Corporation (1919), and the Declaration of the Rights of the Negro Peoples of the World (1920). W. E. B. Du Bois and Dr. Carter G. Woodson used it in the titles of their non-fiction books, The Negro (1915) and The Mis-Education of the Negro (1933) respectively. "Negro" was accepted as normal, both as exonym and endonym, until the late 1960s, after the later African-American Civil Rights Movement. One well-known example is the identification by Martin Luther King, Jr. of his own race as "Negro" in his famous "I Have a Dream" speech of 1963.

However, during the 1950s and 1960s, some black American leaders, notably Malcolm X, objected to the word Negro because they associated it with the long history of slavery, segregation, and discrimination that treated African Americans as second class citizens, or worse.[7] Malcolm X preferred Black to Negro, but also started using the term Afro-American after leaving the Nation of Islam.[8]

Since the late 1960s, various other terms have been more widespread in popular usage. These include black, Black African, Afro-American (in use from the late 1960s to 1990) and African American.[9] The word Negro fell out of favor by the early 1970s. However, many older African Americans initially found the term black more offensive than Negro.

The term Negro is still used in some historical contexts, such as the songs known as Negro spirituals, the Negro Leagues of sports in the early and mid-20th century, and organizations such as the United Negro College Fund.[10][11] The academic journal published by Howard University since 1932 still bears the title Journal of Negro Education, but others have changed: e.g. the Association for the Study of Negro Life and History (founded 1915) became the Association for the Study of Afro-American Life and History in 1973, and is now the Association for the Study of African American Life and History; its publication The Journal of Negro History became The Journal of African American History in 2001. Margo Jefferson titled her 2015 book Negroland: A Memoir to evoke growing up in the 1950s and 1960s in the African-American upper class.

The United States Census Bureau included Negro on the 2010 Census, alongside Black and African-American, because some older black Americans still self-identify with the term.[12][13][14] The U.S. Census now uses the grouping "Black, African-American, or Negro." Negro is used in efforts to include older African Americans who more closely associate with the term.[15]

Liberia

The constitution of Liberia limits Liberian nationality to Negro people (see also Liberian nationality law).[16] People of other racial origins, even if they have lived for many years in Liberia, are thus precluded from becoming citizens of the Republic.[17]

In other languages

Latin America (Portuguese and Spanish)

In Spanish, negro (feminine negra) is most commonly used for the color black, but it can also be used to describe people with dark-colored skin. In Spain, Mexico and almost all of Latin America, negro (lower-cased, as ethnonyms are generally not capitalized in Romance languages) means 'black person'. As in English, this Spanish word is often used figuratively and negatively, to mean 'irregular' or 'undesirable', as in mercado negro ('black market'). However, in Spanish-speaking countries where there are fewer people of West African slave origin, such as Argentina and Uruguay, negro and negra are commonly used to refer to partners, close friends[18] or people in general, independent of skin color. In Venezuela the word negro is similarly used, despite its large West African slave-descended population percentage.

In certain parts of Latin America, the usage of negro to directly address black people can be colloquial. It is important to understand that this is not similar to the use of the word nigga in English in urban hip hop subculture in the United States, given that "negro" is not a racist term. For example, one might say to a friend, "Negro ¿Como andas? (literally 'Hey, black-one, how are you doing?'). In such a case, the diminutive negrito can also be used, as a term of endearment meaning 'pal'/'buddy'/'friend'. Negrito has thus also come to be used to refer to a person of any ethnicity or color, and also can have a sentimental or romantic connotation similar to 'sweetheart' or 'dear' in English. (However, in the Philippines negrito was used for a local dark-skinned, short population native to the Negros islands among other places; this is the meaning of Negrito in English.) In other Spanish-speaking South American countries, the word negro can also be employed in a roughly equivalent term-of-endearment form, though it is not usually considered to be as widespread as in Argentina or Uruguay (except perhaps in a limited regional and/or social context). It is consequently occasionally encountered, due to the influence of nigga, in Chicano English in the United States.

In Portuguese, negro is an adjective for the color black, although preto is the most common antonym of branco ('white'). In Brazil and Portugal, negro is equivalent to preto, but it is far less commonly used. In Portuguese-speaking Brazil, usage of "negro" heavily depends on the region. In the state of Rio de Janeiro, for example, where the main racial slur against black people is crioulo (literally 'creole', i.e. Americas-born person of West African slave descent), preto/preta and pretinho/pretinha can in very informal situations be used with the same sense of endearment as negro/negra and negrito/negrita in Spanish-speaking South America, but its usage changes in the nearby state of São Paulo, where crioulo is considered an archaism and preto is the most-used equivalent of "negro"; thus any use of preto/a carries the risk of being deemed offensive.

Other Romance languages

In Italian, negro / negra were used as neutral term equivalents of "negro", which was used until the end of the 1960s. Nowadays, the word is considered offensive; if used with a clear offensive intention it may be punished by law.

In the French language, the positive concept of negritude ('blackness') was developed by the Senegalese politician Léopold Sédar Senghor. The word nègre as a racial term fell out of favor around the same time as its English equivalent negro. Its usage in French today has shifted completely, to refer to a ghostwriter (i.e. one who writes a book on behalf of its nominal author, usually a non-literary celebrity).

In Haitian Creole, the word nèg, derived from the French nègre, refers to a dark-skinned man; it can also be used for any man, regardless of skin color, roughly like guy or dude in American English.

Scandinavian languages

In Swedish and Norwegian, neger used to be considered a neutral equivalent to "negro". However, the term gradually fell out of favour through the late-1960s, 70s, 80s and 90s.

In Denmark, usage of neger is up for debate. Linguists and others may argue that the word has a historical racist legacy that makes it unsuitable for use today. Mainly older people use the word neger with the notion that it is a neutral word paralleling "negro". Relatively few young people use it, other than for provocative purposes in recognition that the word's acceptability has declined.[19]

In the Finnish language the word neekeri (cognate with negro) was long considered a neutral equivalent for "negro".[20] In 2002, neekeri's usage notes in the Kielitoimiston sanakirja shifted from "perceived as derogatory by some" to "generally derogatory".[20] The name of a popular Finnish brand of chocolate-coated marshmallow treats was changed by the manufacturers from Neekerinsuukko (lit. 'negro's kiss', like the German version) to Brunbergin suukko ('Brunberg's kiss') in 2001.[20] A study conducted among native Finns found that 90% of research subjects considered the terms neekeri and ryssä among the most derogatory epithets for ethnic minorities.[21]

Germanic languages

The Dutch word, neger is generally (but not universally) considered to be a neutral one, or at least less negative than zwarte ('black').[22]

In German, Neger was considered to be a neutral term for black people, but gradually fell out of fashion since the 1970s. Neger is now mostly thought to be derogatory or racist.

Elsewhere

In Turkish, zenci is the closest equivalent to "negro". The appellation was derived from the Arabic zanj for Bantu peoples. It is usually used without any negative connotation.

In Hungarian, néger (possibly derived from its German equivalent) is still considered to be the most neutral equivalent of "negro".[23]

In Russia, the term негр (negr) was commonly used in the Soviet period without any negative connotation, and its use continues in this neutral sense. In modern Russian media, the negr is used somewhat less frequently. Čërnyj as an adjective is also used in a neutral sense, and conveys the same meaning as negr, as in чёрные американцы (čërnye amerikancy or chyornuye amerikantsy: 'black Americans'). Other alternatives to negr are темнокожий (temnokozhiy—dark-skinned), чернокожий (chernokozhiy: black-skinned). These two are used as both nouns and adjectives. See also Afro-Russian.

See also

- Free Negro

- Kaffir (racial term)

- Nigger

- Nigga

- Magical Negro, a trope in fiction

- The Book of Negroes, a historical document

References

- ↑ The American Heritage Dictionary of the English Language. Boston: Houghton Mifflin. 2000. p. 2039. ISBN 0-395-82517-2.

- ↑ Mann, Stuart E. (1984). An Indo-European Comparative Dictionary. Hamburg: Helmut Buske Verlag. p. 858. ISBN 3-87118-550-7.

- ↑ "Negro: definition of Negro in Oxford dictionary (British & World English)". Oxforddictionaries.com. Retrieved 2014-05-11.

- ↑ "Queen Charlotte of Britain". www.pbs.org. Retrieved 2013-05-19.

- ↑ Nguyen, Elizabeth. "Origins of Black History Month," Spartan Daily, Campus News. San Jose State University. 24 February 2004. Accessed 12 April 2008. Archived 2 October 2011 at the Wayback Machine.

- ↑ "6 Shocking Facts About Slavery, Natives and African Americans". Indian Country Today Media Network. Oct 9, 2013. Retrieved 8 July 2016.

- ↑ Smith, Tom W. (1992) "Changing racial labels: from 'Colored' to 'Negro' to 'Black' to 'African American'." Public Opinion Quarterly 56(4):496–514

- ↑ Liz Mazucci, "Going Back to Our Own: Interpreting Malcolm X’s Transition From 'Black Asiatic' to 'Afro-American'", Souls 7(1), 2005, pp. 66–83.

- ↑ Christopher H. Foreman, The African-American predicament, Brookings Institution Press, 1999, p.99.

- ↑ "UNCF New Brand". Uncf.org. Retrieved 2013-05-19.

- ↑ Quenqua, Douglas (17 January 2008). "Revising a Name, but Not a Familiar Slogan". New York Times.

- ↑ U.S. Census Bureau interactive form, Question 9. Accessed 7 January 2010. Archived 8 January 2010 at the Wayback Machine.

- ↑ CBS New York Local News. Accessed 7 January 2010. Archived 9 January 2010 at the Wayback Machine.

- ↑ "Census Bureau defends 'negro' addition". UPI. 2010-01-06. Retrieved 7 January 2010.

- ↑ Mcfadden, Katie; Mcshane, Larry (6 January 2010). "Use of word Negro on 2010 census forms raises memories of Jim Crow". Daily News. New York.

- ↑ Tannenbaum, Jessie; Valcke, Anthony; McPherson, Andrew (2009-05-01). "Analysis of the Aliens and Nationality Law of the Republic of Liberia". Rochester, NY.

- ↑ American Bar Association (May 2009). "ANALYSIS OF THE ALIENS AND NATIONALITY LAW OF THE REPUBLIC OF LIBERIA" (PDF). ABA Rule of Law Initiative.

- ↑ "negro" in the Diccionario de la Real Academia Española

- ↑ Anne Ringgaard, Journalist. "Hvorfor må man ikke sige neger?". videnskab.dk. Retrieved on 2 January 2016.

- 1 2 3 Rastas, Anna (2007). Neutraalisti rasistinen? Erään sanan politiikkaa (PDF) (in Finnish). Tampere: Tampere University Press, 2007. ISBN 978-951-44-6946-6. Retrieved February 2009. Check date values in:

|access-date=(help) - ↑ Raittila, Pentti (2002). Etnisyys ja rasismi journalismissa (PDF) (in Finnish). Tampere: Tampere University Press,. pp. 25–26. ISBN 951-44-5486-3. Retrieved May 2010. Check date values in:

|access-date=(help) - ↑ Van Dale, Groot Woordenboek der Nederlandse taal, 2010

- ↑ See Hungarian sources at the related Hungarian Wikipedia article

External links

| Look up negro in Wiktionary, the free dictionary. |

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to People with black skin. |

"Negro". Collier's New Encyclopedia. 1921.

"Negro". Collier's New Encyclopedia. 1921.