Tlaltenango de Sánchez Román Municipality

Coordinates: 21°46.89′N 103°18.3518′W / 21.78150°N 103.3058633°W

| Tlaltenango de Sánchez Román | ||

|---|---|---|

|

Tlaltenango | ||

| ||

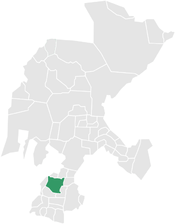

Location within the state of Zacatecas | ||

Zacatecas' location within Mexico | ||

| Coordinates: 21°47′00″N 103°18′00″E / 21.7832°N 103.2999°E | ||

| Country |

| |

| State | Zacatecas | |

| Municipality | Tlaltenango de Sánchez Román | |

| Founded | 1542 | |

| Government | ||

| • Mayor | Miguel Ángel Varela Pinedo | |

| Area | ||

| • Municipality | 747.082 km2 (288.450 sq mi) | |

| Elevation | 1,723 m (5,653 ft) | |

| Population (2005) | ||

| • Total | 21,636 | |

| • Demonym | Tlaltenanguense | |

| Time zone | CST (UTC-6) | |

| Postal code | 99-700 | |

| Area code(s) | (52) 437 | |

| Website | www.tlaltenangozac.gob.mx | |

The municipality of Tlaltenango de Sánchez Román is located in the southwestern portion of the Mexican state of Zacatecas. The average elevation of the municipality is 1,723 meters (5,653 ft) above sea level and the municipality covers an area of 747.082 square kilometres (288.450 sq mi). The municipality lies in a valley bordered by the Sierra de Morones and lies on the banks of the Tlaltenango River, which runs north and is a tributary of the Bolaños River.

The municipality is bordered on the north by the municipalities of Momax and General Joaquin Amaro, to east by the municipalities of Huanusco and Jalpa, to the south by the municipalities of municipality of Tepechitlán and to the west by Atolinga Municipality.

Population

According to the 2005 Census, the municipality of Tlaltenango de Sánchez Román had a population of 21,636 inhabitants. Of these, 14,520 lived in the municipal seat and the remainder lived in surrounding rural communities. In 2000, there were 7,223 economically active individuals in the municipality. The largest sector of employment was agriculture in husbandry, which employed 19.1% of the economically active population, followed by wholesale and retail, which employed 16.8% and manufacturing, which employed 11.9%.

Climate

| Climate data for Tlaltenango de Sánchez Román (1951–2010) | |||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Month | Jan | Feb | Mar | Apr | May | Jun | Jul | Aug | Sep | Oct | Nov | Dec | Year |

| Record high °C (°F) | 33.0 (91.4) |

38.0 (100.4) |

43.0 (109.4) |

45.0 (113) |

43.0 (109.4) |

43.0 (109.4) |

41.0 (105.8) |

35.0 (95) |

38.0 (100.4) |

40.0 (104) |

40.0 (104) |

31.0 (87.8) |

45.0 (113) |

| Average high °C (°F) | 23.9 (75) |

25.5 (77.9) |

27.8 (82) |

30.7 (87.3) |

32.2 (90) |

30.8 (87.4) |

27.9 (82.2) |

27.7 (81.9) |

27.7 (81.9) |

27.4 (81.3) |

26.6 (79.9) |

24.6 (76.3) |

27.7 (81.9) |

| Daily mean °C (°F) | 13.3 (55.9) |

14.4 (57.9) |

16.6 (61.9) |

19.3 (66.7) |

21.7 (71.1) |

22.5 (72.5) |

20.9 (69.6) |

20.7 (69.3) |

20.4 (68.7) |

18.5 (65.3) |

15.8 (60.4) |

14.0 (57.2) |

18.2 (64.8) |

| Average low °C (°F) | 2.7 (36.9) |

3.4 (38.1) |

5.1 (41.2) |

8.0 (46.4) |

11.1 (52) |

14.2 (57.6) |

13.9 (57) |

13.6 (56.5) |

12.9 (55.2) |

9.5 (49.1) |

4.9 (40.8) |

3.4 (38.1) |

8.6 (47.5) |

| Record low °C (°F) | −8.5 (16.7) |

−6.0 (21.2) |

−5.0 (23) |

−1.0 (30.2) |

3.0 (37.4) |

5.0 (41) |

5.0 (41) |

4.0 (39.2) |

2.0 (35.6) |

−1.5 (29.3) |

−4.0 (24.8) |

−6.5 (20.3) |

−8.5 (16.7) |

| Average precipitation mm (inches) | 19.9 (0.783) |

10.2 (0.402) |

5.0 (0.197) |

8.5 (0.335) |

18.3 (0.72) |

130.5 (5.138) |

198.2 (7.803) |

168.8 (6.646) |

115.0 (4.528) |

40.8 (1.606) |

10.7 (0.421) |

15.0 (0.591) |

740.9 (29.169) |

| Average precipitation days (≥ 0.1 mm) | 2.9 | 1.6 | 0.6 | 1.0 | 3.0 | 11.7 | 17.7 | 16.5 | 12.2 | 5.6 | 1.7 | 2.4 | 76.9 |

| Source: Servicio Meteorologico Nacional[1][2] | |||||||||||||

History

In 1530, the Valley of Tlaltenango was inhabited by the indigenous Caxcans who farmed the land on the river banks and certainly enjoyed the abundance of flora and fauna of the mountain ranges that surrounded the valley. The meaning of the word Tlaltenango in the Caxcan language (land surrounded by walls) alludes to the mountainous landscape of the valley.

Between these walls, the Sierra del Mixtón to the east and the Sierra de Tepeque to the west, transited Nuño Beltrán de Guzmán and his soldiers, leaving, according to the historian Peter Gerhard, “a path of corpses and destroyed houses and crops, impressing surviving males into service and leaving women and children to starve.” Frame 56 of the Lienzo de Tlaxcala describes a battle in which the Caxcans of “Tlaltenapa” defended their lands against the Spanish and their Tlaxcaltec allies.

The memories of this first encounter with the Spanish must have tormented the inhabitants of Tlaltenango and its surrounding area. So great was the anguish that in 1531, from the mountains near El Teúl, they launched an attack against the Spanish who were attempting to build a town named the Town of the Holy Spirit of Guadalajara near what is now Nochistlán. The Town of Guadalajara was left in ruins and the Spanish had to make another three attempts before the town finally survived in its present location (the Atemajac Valley) where it was built in 1542.

In 1541, the Caxcans took up arms against the Spanish once again, with their Tepehuan, Zacatec and Guachichil allies. From the Sierra del Mixtón, which is today known as Sierra de Morones, the indigenous allies of the region attacked the Spanish. The Mixtón War lasted less than two years, but peace was not long-lived. In 1550, the seeds of war sprouted once again with the great Chichimeca War, a war fought by a great number of Chichimec ethnic groups (Chichimec was a pejorative term used by civilized ethnic groups of the south to describe the nomadic ethnic groups of the north). This war lasted almost forty years. While it seems that the residents of the Valley of Tlaltenango did not participate in this rebellion, the region suffered the consequences of war nevertheless due to the chaos all around it. For having submitted to the Spanish Crown, The Caxcan towns of the area around Tlaltenango suffered attacks from the north launched by their former allies, the Zacatecs.

The war only came to an end when the Viceroy Luis de Velasco decided to purchase peace with the Chichimecs. As part of the peace offering, the Viceroy used the power of the Royal Treasury to dissitribute clothing, tools and food to the Chichimecs in return for their pacification and recognition of the Spanish Crown. In addition, he recruited hundreds of Tlaxcaltec families to move and live among the Chichimecs so as to convert them to the Catholic faith and to a sedentary lifestyle by teaching them agricultural methods.

Needless to say, at the end of the 16th century there were very few Spaniards that lived in the vicinity of Tlaltenango. In the decade of 1540, probably after the Mixtón War, the towns of the valley were entrusted as encomiendas to a number of Spaniards. The town of Tlaltenango was entrusted to Toribio de Bolaños, Tepechitlán to Pedro de Bobadilla, a soldier of Nuño Beltrán de Guzmán, and El Teúl was an encomineda of Juan Delgado. It is unlikely that these individuals were able to exercise their rights over the indigenous populations during the 16th century, given that the successive rebellions would have made it difficult. However, with the end of war, Spaniards began arriving and settling among the newly pacified indigenous inhabitants of the region.

In 1550, the town of Tlaltenango had 132 houses, in which lived 626 persons. By 1561, the tributary population (adult males) reached 379. In 1570, the tributary population had reached 1,000 individuals and there were 20 Spaniards living in the town of Tlaltenango. The valley had more than 8,000 inhabitants. Such a rapid increase in population indicates a great inflow of migrants into the region during that time. Three years later, most certainly due to disease and war, the population of the town had decreased to only 380 tributaries. By 1584, the population had still not recovered, as there were just over 3,000 inhabitants, nearly all indigenous. These inhabitants were nourished by the corn, chile and beans that they would sow in their farms along the Tlaltenango River, by peaches, quinces, figs and cactus pears that grew in the valley and by chickens and turkeys that they raised.

By 1616, the number of Spaniards in the Valley was high enough for the indigenous inhabitants to complain about the damages caused to their farms by the steer and horses of the Spaniards. Racial mixing between the Spanish and Amerindians of the region existed in those early years. The documented complaints of the indigenous inhabitants include the extramarital affairs of Diego González and Diego López, both Spaniards, with Indian women and those of Juan de Miramontes, also a Spaniard, with a mestizo woman who was the wife of a Tlaxcaltec. We also know that the Bobadilla, trustees of Tepechitlán, were mestizos, since the first trustee, Pedro de Bobadilla married and had offspring with an indigenous woman.

The local indigenous population was the main supply of labor for the salt mines in Santa Maria y El Peñol Blanco in the early 17th century. The town and its surrounding wooded mountains were also key suppliers of wood fiber used for construction of the frontier towns of Jerez and Colotlán. The jurisdiction of Tlaltenango included at least three sawmill and charcoal plants in the 17th century.

On July 18, 2008 there was a massive flash flood, killing 3, and affecting 15,000 of the town's people.

References

- ↑ "Estado de Zacatecas-Estacion: Tlaltenango de Sánchez Román". Normales Climatologicas 1951–2010 (in Spanish). Servicio Meteorologico Nacional. Retrieved 22 April 2015.

- ↑ "Extreme Temperatures and Precipitation for Tlaltenango de Sánchez Román 1961–2010" (in Spanish). Servicio Meteorológico Nacional. Retrieved 22 April 2015.

Sources

- Enciclopedia de los Municipios de Zacatecas, State of Zacatecas

- Insituto Nacional de Estadística, Geografía e Informática

- Carlos Casas, Bernardo. Tlaltenango: una ciudad amurallada, Guadalajara, Jal.: Impre-Jal (1986)

- Gerhard, Peter. The North Frontier of New Spain, Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press (1982)

- Salcedo y Herrera, Francisco Manuel. Descripción del partido y jurisdicción de Tlaltenango, hecha en 1650, México, D.F.: José Porrua e Hijos (1958)

External links

- En el Valle de Tlaltenango (Somos Primos article in Spanish)

- www.mytlaltenango.com (Private party site dedicated to Tlaltenango (in Spanish))

- Red Social De Tlaltenango (Tlaltenango Social Network)